A SPECIAL EDITION OF CVM TODAY

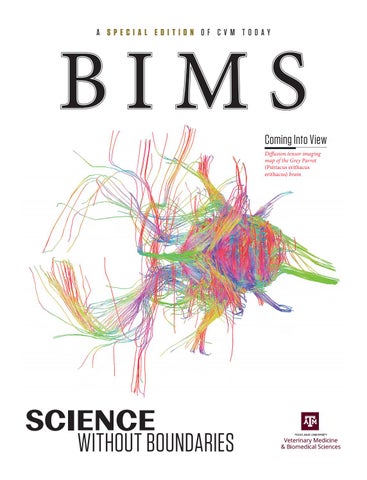

Coming Into View Diffusion tensor imaging map of the Grey Parrot (Psittacus erithacus erithacus) brain

DEAN'S MESSAGE

The biomedical sciences program (BIMS) is an integral part of the College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (CVM). Not only does it represent half of our college’s name, but BIMS students represent about 46 percent of all Aggies enrolled in our veterinary school. After its recent seven-year academic review, we observed an interesting phenomenon—the BIMS program is, as one faculty member recently put it during a forum at which we discussed the program, “bursting at the seams.” With close to 2,400 students, almost a thousand more than in 2011, the year of the last academic review, the BIMS program is more popular than ever. It is the largest degree-granting program at Texas A&M and is helping to fulfill a crucial need in the state of Texas—that of more medical professionals. Looking at the BIMS program on the outset, it’s easy to connect it to the concept of “Science without Boundaries.” The program prepares students for a wealth of career paths, from the traditional, medically oriented professions to the less-traditional areas of health care administration or occupational health and safety. Our students are entering the veterinary profession and also are gaining admission to medical and dental schools at rates significantly higher than the national average. They’re going to graduate school and earning their master’s and doctoral degrees. And then they’re going out into the world and making an incredible impact on society. Walking around the halls of the Veterinary & Biomedical Education Complex (VBEC) or taking a peek

into the Biomedical Sciences Office, especially during advising periods, you can see the theme of “Science without Boundaries” playing out among the people themselves. Whether it’s the countries represented by the faculty, staff, and students, or the destinations they visit through the BIMS program’s active research and study abroad programming, the opportunities for BIMS students to expand their cultural horizons and gain new context about the impact they can make are limitless. But even more than that, while the BIMS faculty are certainly invested in the science behind biomedical sciences, through both their research and their teaching, they also prove that they are invested in guiding students who are more than just scientists, but who also are citizens of the world. In our BIMS Magazine, we hope to show you how the BIMS program embraces “Science without Boundaries” philosophically, expanding beyond what one might traditionally consider a biomedical sciences education. The faculty, renowned and highly respected in their own right, work hard to break down the “boundaries” of science in the groundbreaking research they conduct, but also of what science education means. You will see over and over in these articles that our faculty are teaching more than genetics and physiology; they’re using genetics and physiology to encourage innovation, ingenuity, and creativity, focusing on the importance of communication, art, social awareness, and compassion. By correlating those topics with the biomedical sciences fields, students see the myriad of opportunities available to have an impact on, or be impacted by, communities around the world. Simultaneously, they’re developing themselves as people through the classes they take, the research with which they assist, and the countries to which they travel. It truly is an amazing time in our college.

Eleanor M. Green, DVM, DACVIM, DABVP The Carl B. King Dean of Veterinary Medicine

COVER FEATURE

BIMS alumnus Scott Echols is revolutionizing the field of medical imaging.

42

ON THE COVER

Colorful Lines

The image on the cover is a Diffusion tensor imaging map of the Grey Parrot (Psittacus erithacus erithacus) brain. This specialized MRI technique elucidates the location, property differences, and orientation of white matter tracts. The same technique can be applied to muscle and other fibers within the body. Each colored line represents a brain tract. The different colors represent the change in direction of the nerve tract in the x, y, and z plane. The cerebellum is to the right and the cerebrum to the left of the picture. Special thanks to Dr. Ed Hsu and his bioengineering team at the University of Utah.

// SPECI A L ISSU E

TABLE OF CONTENTS

04.....BIMS History 05.....BIMS Faculty 06.....BIMS Infographics

LEADERSHIP 08.....A Conversation with Crouch 12......Dedicated to Student Success

ALUMNI

Editor-in-Chief: Dr. Megan Palsa ’08 Managing Editor: Jennifer G. Gauntt Contributing Writers: Kasey Heath ’18 Rachel Hoyle ’13 Briley Lambert ’18 Callie Rainosek ’17 Chad Wootton Art Director: Christopher A. Long

14......Hitting the Right Notes 18......Having a Hand in Healing 22.....BIMS Board Focuses on Mentorship, Scholarships

Graphic Designers: VeLisa W. Bayer Jennie L. Lamb

TEACHING

Correspondence Address: CVM Today Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences Texas A&M University 4461 TAMU College Station, TX 77843-4461

24.....Experiential Learning with Dr. J 28.....Into the Wild 30.....A World of Opportunities

SPOTLIGHTS 42.....Coming Into View 48.....Science-Driven Siblings

OUTREACH 54.....The 'A'mbassador Team 58.....Getting 'Organized'

CURRICULUM 60.....Designed to Inspire 64.....Quick Thinking 68.....Abby's ABCs 72......Program Expands to McAllen 74......Certificates 02 | BIMS MAGAZINE // FALL 2018

MAGAZINE STAFF

Photographer: Tim Stephenson

BIMS: A Special Edition of CVM Today is published by the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences for alumni and friends. We welcome your suggestions, comments, and contributions to content. Contact us via email at cvmtoday@cvm.tamu.edu. A reader survey is available online at: tx.ag/cvmtodaysurvey. Permission is granted to use all or part of any article published in this magazine, provided no endorsement of a commercial product is stated or implied. Appropriate credit and a tear sheet are requested.

CVM INFORMATION COLLEGE ADMINISTRATION The Carl B. King Dean of Veterinary Medicine Dr. Eleanor M. Green Executive Associate Dean Dr. Kenita S. Rogers ’86 Associate Dean, Professional Programs Dr. Karen K. Cornell Associate Dean, Research & Graduate Studies Dr. Robert C. Burghardt Associate Dean, Undergraduate Education Dr. Elizabeth Crouch ’91 Associate Dean, Global One Health Dr. Gerald Parker Jr. ’77 Assistant Dean, Research & Graduate Studies Dr. Michael Criscitiello Assistant Dean, Hospital Operations Mr. Bo Connell Assistant Dean, Finance Ms. Belinda Hale ’92 Interim Dept. Head, Veterinary Integrative Biosciences Dr. C. Jane Welsh Dept. Head, Veterinary Pathobiology Dr. Ramesh Vemulapalli

College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences Texas A&M University | 4461 TAMU College Station, TX 77843-4461 vetmed.tamu.edu Dean’s Office & Administration 979.845.5051 Admissions 979.845.5051 Biomedical Sciences Program 979.845.4941 Development & Alumni Relations 979.845.9043 CVM Communications 979.845.1780 Continuing Education 979.845.9102 Graduate & Research Studies 979.845.5092 Global One Health 979.845.8612 Public Relations 979.862.4216 Veterinary Integrative Biosciences 979.845.2828

Dept. Head, Veterinary Physiology & Pharmacology Dr. Larry J. Suva

Veterinary Pathobiology 979.845.5941

Dept. Head, Large Animal Clinical Sciences Dr. Susan Eades

Veterinary Physiology & Pharmacology 979.845.7261

Dept. Head, Small Animal Clinical Sciences Dr. Jonathan Levine

Small Animal Clinical Sciences 979.845.9053

Assistant Vice President for Development (Texas A&M Foundation) Ms. Chastity Carrigan ’16

Large Animal Clinical Sciences 979.845.9127

Chief of Staff Ms. Misty Skaggs ’93

Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital Administration 979.845.9026

Director, Texas Institute for Preclinical Studies Dr. Egeman Tuzun

Small Animal Hospital 979.845.2351

Executive Director, Communications, Media, & Public Relations Dr. Megan Palsa ’08

Large Animal Hospital 979.845.3541

FALL 2018 \\ BIMS MAGAZINE | 03

BIMS HISTORY

by Jennifer Gauntt

Alvin A. Price was the dean at the time the BIMS program was founded. He was its director after his deanship from 1975-1989.

04 | BIMS MAGAZINE // FALL 2018

In 1972, the College of Veterinary Medicine Dean Alvin A. Price and others realized the need for an undergraduate program to fill gaps in the existing pre-veterinary program. Thus, the college’s first undergraduate program, in biomedical sciences (BIMS), was established. Initially focused on producing well-trained veterinary technicians— offering courses in surgical support, parasitology, and other topics required for that field—the program gained the attention of other professional schools, and administrators decided to broaden the program’s scope to include many pre-professional medical and health fields serving both humans and animals. The decision has had long-lasting effects for both the program and the college. In 2004, the name of the college was changed to the College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (CVM), in part to convey the message that, in addition to training future veterinarians, the college is committed to educating future biomedical scientists at both the

graduate and undergraduate levels. Additionally, the initial enrollment of 10 students, which had grown to 913 in just three years, today stands at approximately 2,500 students who choose the BIMS program for the strong, four-year education it provides in the broad field of applied biology related to health and disease. Graduating approximately 400 students with bachelor’s degrees each year, BIMS is now the largest degree-granting program at Texas A&M; these graduates enter health and science related fields in research, hospitals, governmental agencies, and industry, as well as go on to professional schools for medicine, dentistry, nursing, and veterinary medicine, among others. The BIMS mission is clear— preparing students for futures in a changing world, while orienting and training themselves in areas of selected biomedical vocational interest, is the primary focus for the faculty and administrators who teach to the diverse, well-rounded student population. ■

BIMS FACULTY VIBS

VSCS

Louise C. Abbott Sakhila Arosh Fuller Bazer Marvin Cannon Tamy C. Frank-Cannon Weihsueh A. Chiu Kevin O. Curley Brian W. Davis William L. Dees Dana Gaddy Barbara J. Gastel Sarah A. Hamer Yasha M. Hartberg Jill K. Hiney Sharman Hoppes Nancy H. Ing Gregory A. Johnson Larry Johnson William Klemm Gladys Ko Candice L. Brinkmeyer Langford Jianrong Li Erica R. Malone William J. Murphy Peter P. Nghiem Timothy D. Phillips Michelle D. Pine Weston W. Porter Terje Raudsepp Lynn M. Ruoff James R. Snell Robert J. Taylor Vijayanagaram Venkatraj Micah J. Waltz Christabel Welsh Michelle S. Yeoman

Kate E. Creevy Jennifer J. Heatley Sharman M. Hoppes William B. Saunders Erin M. Scott Joerg M. Steiner Jan Suchodolski Debra L. Zoran

VETERINARY INTEGRATIVE BIOSCIENCES

VLCS

LARGE ANIMAL CLINICAL SCIENCES Noah D. Cohen Dickson D. Varner Ashlee E. Watts

SMALL ANIMAL CLINICAL SCIENCES

VTPB

VETERINARY PATHOBIOLOGY Donald J. Brightsmith Walter E. Cook Michael Criscitiello James N. Derr Scott V. Dindot Maria Esteve-Gasent Sara D. Lawhon Linda L. Logan Albert Mulenga Jeffrey MB Musser Mary B. Nabity Mohamed T. Omran Susan L. Payne Sanjay M. Reddy Gonzalo M. Rivera David W. Threadgill Deborah S. Threadgill Ian Tizard Kenneth E. Turner Bradley R. Weeks

Guichun Han James D. Herman Katrin Hinrichs Ivan Ivanov Daniel H. Jones Glen A. Laine Charles R. Long Luke C. Lyons Alice R. Blue Mclendon Ken Muneoka Anne E. Newell-Fugate Christopher M. Quick Jayanth Ramadoss Stephen H. Safe John N. Stallone Larry J. Suva Shannon E. Washburn Jeremy S. Wasser

Dr. Sarah A. Hamer, director of the Schubot Exotic Bird Health Center

VTPP

VETERINARY PHYSIOLOGY & PHARMACOLOGY Tracy M. Clement Fred J. Clubb Amanda R. Davis Ranjeet M. Dongaonkar Virginia R. Fajt Michael C. Golding

Christopher Quick teaching his undergraduate students FALL 2018 \\ BIMS MAGAZINE | 05

BIMS INFOGRAPHICS

BIOMEDICAL SCIENCES (BIMS) Texas A&M University offers a distinctive undergraduate program in biomedical sciences (BIMS) at the CVM. BIMS is a broad field of applied biology that is directed toward understanding health and disease. The curriculum provides a strong four-year education that emphasizes versatility of the graduate in the biological and medical sciences. A highly effective academic counseling program helps students develop individualized course packages that orient and prepare them for entry into the medical, allied health, or graduate program of their choice. Such an approach enhances their educational experiences, improves their placement in professional and graduate programs, and facilitates their entry into the biomedical science job market. The mission is to educate students who will create a healthier future for humans and animals through medical professions, biomedical innovation and discovery, global service, and outreach. BIMS is the largest degree-granting undergraduate program at the university, with an enrollment of 2,355 students in 2017–18.

SCHOLARSHIPS

$108,500 TOTAL DISTRIBUTION

4.1%

RECEIVED SCHOLARSHIPS FROM BIMS

06 | BIMS MAGAZINE // FALL 2018

96 out of 2,355 Students received scholarships

$75,000

Differential Tuition Fund awarded

21 students

Received named scholarships

8 scholarships Given by BIMS Board members

STUDENT DEMOGRAPHICS Gender

Ethnicity

First-Generation Students

Hispanic 27.8%

Male 31.4% Female 68.6%

Yes 27.4%

White 50.8%

No 72.6%

Asian 12.9%

Black 5.3% Other 0.6%

Multi-Racial Excl. Black 2.6%

PROFESSIONAL SCHOOL APPLICATION RATES

39%

of Aggie students who enrolled in medical school are BIMS majors

41%

of Aggie students who enrolled in dental school are BIMS majors

46%

of Aggie students who enrolled in veterinary school are BIMS majors

FALL 2018 \\ BIMS MAGAZINE | 07

LEADERSHIP

A Conversation with ELIZABETH CROUCH As associate dean of the CVM’s Biomedical Sciences undergraduate program, Elizabeth Crouch is devoted to ensuring students have a holistic educational experience that ties book learning with practical application. Story by Jennifer Gauntt

08 | BIMS MAGAZINE // FALL 2018

Our mission is to educate students who

will create a healthier future for humans and animals through the medical professions, biomedical innovation and discovery, global service, and outreach. - ELIZABETH CROUCH

As a Texas A&M alumna who started her career in research and teaching, what made you decide to move into administration? I think it was an “organic” move. I have always enjoyed the teaching aspect of my career, whether it was mentoring high school students in the laboratory, acting as a teaching assistant in graduate school, or teaching my own course. When I began to think about the layout of my career and where I would like to be, I was very drawn to the “people” aspect. Advising students was a way for me to directly impact a person’s education and to encourage them through both the difficult times and the celebratory times. My grandfather also put a very strong emphasis on education, which was passed to his daughter (my mother) and, subsequently, me. I feel it is a gift to oneself, and I enjoy being able to facilitate people’s educations and dreams. You’ve been involved with the BIMS program—as an adviser, director, assistant dean, and now associate dean— for a significant portion of your career at Texas A&M. How has the BIMS program changed since its early days? I have been a part of the BIMS program since 1987, minus the nine years I was completing a graduate degree and postdoc. I began as a freshman student at Texas A&M in the BIMS program. At that time, it was primarily premedical, pre-veterinary medical, and pre-dental studies. It was a bit odd that I would choose BIMS, knowing I did not wish to attend one of those three schools. It was also quite small. I think there were approximately 800 students, total, which is now the size of our freshman class—that may not be the official number back in 1987, but it is what I recall. We have also branched out significantly in the number of careers for which our major prepares students; we emphasize One Health and applied biology as it pertains to health and healthcare. I feel this has always been an attractive feature of the biomedical sciences program. Since its establishment in 1970, the program has become the largest degree-granting program at Texas A&M, with approximately 2,400 students. What makes BIMS different than other degrees that focus on the sciences or medicine? I feel that we have a strong track record of students entering professional programs after graduation, as well as a great number of graduate programs and careers in the life

sciences. BIMS’s flexibility, I feel, is attractive to prospective students. I also feel that our high-impact practices and emphasis on the clinical aspects of health and disease are attractive to students. Likewise, the program itself boasts significant success in helping students gain admission to medical school (39 percent of Aggie students who enrolled in 2018 were BIMS majors), dental school (41 percent of Aggie students who enrolled in 2018 were BIMS majors), and veterinary school (46 percent of Aggie Students who enrolled in 2018 were BIMB majors). What is it about the program, or about the students themselves, that makes them so successful? I feel that student success is multi-fold. First, we have very driven, high-quality students who excel not only in the classroom, but also in their activities. They volunteer in many people-centered activities and shadow in the biomedical environment, perform original research, and take advantage of studies abroad. Second, we have an advising office that is present to help and guide students from their New Student Conference through graduation. Our advisers interact with every major office on campus, participate in task forces and committees, and are very knowledgeable of campus resources. Third, our faculty are invested in teaching at the highest levels. They continually develop new content, integrate concepts between disciplines, team teach, and teach with technology. Further, they create rigorous learning laboratories, as well as have research laboratories in which our students participate. Our students learn from faculty from five departments because we are a program within the Dean’s Office. What are some of the components of the BIMS curriculum and programming that makes it stand apart from other programs across campus? As I like to tell our students and prospective students, our faculty only teach one way. In other words, they are rigorous because they also teach in our graduate and professional curriculum; they know what they expect a professional student to know on “day one,” and, therefore, they teach our students so that they will succeed in professional school. We are also unique in that we have an International Certificate in Cultural Competency and Communication in Spanish (Spanish certificate) FALL 2018 \\ BIMS MAGAZINE | 09

to teach students medical Spanish. Certificate students are required to study abroad and to shadow/work in the biomedical environment while using the Spanish language. Our Biomedical Research Certificate is also a strong component/option for students, through which they learn the scientific process; produce original research, which is often able to be published; and lead research teams. Our foundational courses: Biomedical Anatomy, Biomedical Physiology, Biomedical Microbiology, and Biomedical Genetics, emphasize clinical correlates, health, and disease. Three of the four courses also have a significant laboratory component, as do other electives our students take. Finally, the pedagogy in our classes is often creative. For example, Honors Biomedical Anatomy teaches students anatomy using visual arts, including drawing, painting, sculpting, and movement in front of green screens, in addition to the traditional laboratory. One of the things that Texas A&M is extremely proud of is its commitment to study abroad programming. BIMS students are also quite active in studying in other countries and the program offers courses and semester abroad in countries around the world. In your opinion, why is studying abroad important for a BIMS student? (READ MORE ABOUT BIMS STUDY ABROAD ON PAGE 30).

Last year, 30 percent of our undergraduates studied abroad. I feel that studying abroad is important on many levels. For some, it is their first time out of the state of Texas, as well as the country, at a time when students are, by definition of obtaining a college degree, expanding their horizons. Students who study abroad have opportunities to learn from professors who employ different pedagogies than those used in the states, to apply concepts in the field—usually literally—to live in a different environment— homestays, often—and to learn to do the basics in a foreign city—navigate shops, exchange money, and, in some cases, converse. I also feel that studying abroad gives students a new feel for the age of various civilizations as compared to the United States, as well as independence in a way that they may not have when in Texas. They are separated from their jobs, their resources, and their friends and, therefore, must stretch to function in a new culture. Likewise, there is a huge emphasis placed on undergraduate research. What benefits do both students and faculty gain from this kind of scholarly endeavor on an undergraduate level? Fifty percent of our undergraduates perform research prior to graduation. The benefit of undergraduate research to the professor is the opportunity to teach the next generation of researchers and to ignite interest in their specific field. Further, it gives professors help in the laboratories with performance of experiments and an avenue for mentorship for graduate students. For the undergraduate student, research is an experience that teaches them how to read 10 | BIMS MAGAZINE // FALL 2018

primary literature in their field; communicate, both written and verbally; work in teams; and create hypotheses and design experiments. Furthermore, students learn that science is a living, breathing subject that evolves with discovery and that discoveries are still waiting to be made. You’ve talked before about some of the non-traditional career paths that a BIMS degree sets students up for. What are some of those, and how do those career paths align with the needs of the state and country, in terms of job demand in those fields? The healthcare industry is in need of professionals in all aspects, particularly with the aging U.S. population. Additionally, research companies and universities must also replenish scientists and entrepreneurs continually in order to advance medical discoveries. So, alternative career paths to medical, veterinary medical, and dental school fill some of those niches, such as scientific research, allied health sciences (nursing, pharmacy, physical therapy, etc.), and health care administration, to name a few. What would you want students who are considering BIMS as a major, and their parents, to know about the program? The biomedical sciences degree is a rigorous, applied biology degree with a focus on health and healthcare. Our mission is to educate students who will create a healthier future for humans and animals through the medical professions, biomedical innovation and discovery, global service, and outreach. We teach from a One Health perspective, as human, animal, and environmental health are interconnected. With respect to preparation for our major, students should take as much math and science as possible in high school; should not skip senior-year math in high school and should take an advanced science, such as AP biology or AP physics, as well. Students should also realize that this major has six semesters of chemistry: two of inorganic, two of organic, and two of biochemistry; thus, adequate preparation in chemistry and math are essential. Moving back to you, as the BIMS leader, what do you see as your biggest accomplishment during your tenure working within the BIMS program? What has been your biggest challenge? It is difficult for me to say what my biggest accomplishment is because we are very much a team in BIMS. One area that has expanded over the years that I feel I had a role in promoting in the early 2000s is study abroad opportunities, as well as the Spanish certification. We have outstanding faculty in the CVM who have designed unique and challenging studies abroad for our students; they drive the expansion of our programs. And we have two advisers and our director, in particular, who advise our study abroad and certificate students, facilitate their experiences, and process paperwork: Leanne Burck, Kaitlin Hennessy, and Dr. Henry Huebner (our director).

I would say the biggest challenge on our plate these next two years is the initiation of the Biomedical Sciences Program in McAllen. It is amazing to me the number of people it takes to coordinate the building, the facilities, the student services, academic offerings, advising of students, etc. Our first class of students begins this fall. (READ MORE ABOUT THE BIMS PROGRAM IN MCALLEN ON PAGE 72).

Outside of your biggest accomplishment, what are you most proud of? Last spring, I received the Association of Former Students’ Distinguished Achievement Award for “Individual Student Relations.” I am extremely proud and humbled by this award, as I feel that undergraduate advising and teaching are my places to make a difference in the world. I decided to devote my career to undergraduate education because I am continually amazed by our young people; they are intelligent, people-centered, outreach-oriented individuals. They are curious and excited about their future. I have found that I like and tend to be good at guidance and problem-solving. I value learning about individuals and their gifts and enjoy seeing students blossom as they discover their strengths. If I can be of help in that process and help to create an environment in BIMS that facilitates their growth, then I have accomplished my job. Being an administrator can often mean that your exposure to students decreases drastically. How do you stay connected to the BIMS students? I actually still see quite a few students through the advising office. I also teach a course every spring, give the dean’s talk at New Student Conferences, fill in for the prospective students’ talk when needed, and give a large number of the change-of-major meetings. Therefore, I find there are still many ways in which I interact directly with our student population. One of the things, ironically, that I have always told my bosses as I moved up was that I didn’t want to lose contact with the students; they are the source of my excitement about the job and by interacting with them, I find I can be creative about programming ideas, etc. I also love the teaching aspect of my job because my Ph.D. is in genetics and I truly love trying to pass along that particular passion to the next generation of teachers and learners. Drs. David Busbee, Evelyn Tiffany-Castiglioni, Jane Welsh, and Van Wilson were on my graduate committee and all are outstanding educators and mentors. As you moved up the ranks in the BIMS program as director and dean, you became the first woman to hold a director position in the BIMS program’s history. What was that like for you? Has that shaped how you have chosen to lead? I have had very good mentors and role models for leadership, both male and female. My mother was ordained an Episcopal priest in the mid-’80s, when there were very few female priests. I also had the benefit, as a female

scientist, of the generations who went before me and paved the way for women in the sciences. So, from the standpoint of it feeling novel to me, I would say it did not. However, I do think that the older my daughters get, the more I empathize with college-aged students and I feel that the Biomedical Sciences program’s staff practices a type of advising where we are attempting to not only help students navigate academic waters, but where we are also attempting to refer them properly, should they have general questions about Texas A&M, employment, and the skill sets required to be life-long learners and professionals. Texas A&M and the CVM really embrace diversity. Do you have any thoughts on diversity within the BIMS program? What does the college and your program do to encourage diversity? The BIMS program has two student representatives on the Council for Diversity and Professionalism that Dr. Kenita Rogers (CVM executive associate dean) chairs for the college. They have made some suggestions for making students feel at home and integrating creative activities into their semesters that we would like to pursue. Also, we are just under (the ratio of) 1 in every 2 students (48 percent) identifying as ethnically diverse; therefore, we have a wonderful opportunity for students to enrich their lives in our major and study with their future colleagues. Additionally, since we teach from a One Health perspective, our pre-veterinarians are studying with our pre-medical students and our pre-pharmacy students, etc. They will run into each other in life and hopefully those bonds will remain. Finally, we have a diversity of ways students can get a BIMS degree: as freshmen on the College Station campus, as freshmen on the McAllen campus, and as transfer students, many of whom come from our 2+2 community college agreement schools, a significant legacy of our former assistant dean, Dr. Frank “Skip” Landis. Looking into the future, what goals do you still have for the BIMS program? Are there any trends within biomedical sciences that you see the program working toward in the future? I think our biggest goals, broadly speaking, are to continue to design creative classes that capture our students' imaginations in order to provide them an exciting education, and to continue to embrace our diversity and to capitalize on the cultural resources we have to make students feel welcome and want to continue in our college.

(READ MORE ABOUT UNIQUE BIMS CLASSES ON PAGE 60). ■

For more information about the BIMS program, visit vetmed.tamu.edu/bims.

FALL 2018 \\ BIMS MAGAZINE | 11

D

E

D

I

C

A

T

E

D

T

O

AS DIRECTOR OF THE BIMS UNDERGRADUATE PROGRAM, DR. HENRY HUEBNER WORKS ALONGSIDE DR. ELIZABETH CROUCH

TO ENSURE STUDENTS SUCCEED BOTH AS UNDERGRADUATES AND IN THEIR CAREERS. by Dr. Megan Palsa

With a background in research and training in toxicology, Dr. Henry Huebner understands the rigorous requirements of the biomedical sciences (BIMS) undergraduate degree program. Huebner earned three degrees at Texas A&M University: a Bachelor of Science in agronomy, a Master of Science in soil science, and a doctorate in toxicology. He started what has become his 25 years of service in the Texas A&M University College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (CVM) as a Technician II in the Department of Veterinary Anatomy & Public Health— now called the Department of Veterinary Integrative Biosciences (VIBS). In 2002, after finishing his doctorate, he continued working with Dr. Timothy Phillips as an assistant research scientist, working on environmental and mycotoxinrelated projects, and as an editorial assistant for the Journal of Food Additives & Contaminants. 12 | BIMS MAGAZINE // FALL 2018

In 2006, Huebner accepted a position allowing him to be more active in counseling students and helping them focus on their career objectives and goals. He began working in the BIMS program as a senior academic adviser and lecturer before being promoted to director in July 2014. Huebner grew up in the small town of Schulenburg, Texas, where his family was involved in teaching in public and private schools. They also were active in farming and agriculture, raising cattle, sheep, and chickens and harvesting hay, pecans, fruit, and vegetables. Looking back, he feels that his background instilled in him the importance of family, hard work, service, teamwork, and responsibility. “The BIMS program’s attributes that impress me the most include the quality, spirit, and determination of the students in our program and the excellence and service of our faculty, staff, and administration,” Huebner said. “One

DR. HENRY HUEBNER

of the main responsibilities I have is to assist the associate dean with keeping program operations on course. I assist with developing/revising office policies and implementing improvements to enhance operation efficiency.” Throughout the year, he assists Dr. Elizabeth Crouch, the associate dean, with strategic planning and preparations for future student enrollment challenges. “I continue to advise students regarding academic schedules, course planning, and selections and also approve degree plans, course substitutions, add/drop, Q drops, withdrawals, and changes of curriculum,” Huebner said. “I monitor student probationary terms, perform senior degree audits, verify completion of degree requirements, and assist in graduation functions. I am the instructor of BIMS 484, a field experience elective course offered to juniors and seniors.” Huebner has represented the program in the University Freshmen and Transfer Student Recruitment Committee, Office of the Registrar’s Compass Advisor User Group, Biomedical Sciences Undergraduate Scholarship Review Committee, and University Advisors Council Executive Committee. He currently serves on the Texas A&M Scholarships and Financial Aid Advisory Committee,

Admissions Appeals Committee, and New Student Conference Committee. “Dr. Crouch and I have the same vision and goals for the continued success of the BIMS undergraduate program. Student success in academics and life is a goal all of us in the office share,” Huebner said. “There are many stories of student successes and accomplishments; each person’s story is unique and special, whether it is broadening one’s intellectual and personal horizons through a study abroad experience, acceptance to a professional school, embarking on a career in research, industry, or community service, or simply graduating with their A&M degree.” Huebner said he feels that the BIMS program provides students with a high-quality undergraduate experience. “Our faculty, administration, and office staff are sincerely interested in helping our students, and we are dedicated to serving our students’ needs,” Huebner said. “We take pride in seeing them develop educationally and on a personal level, and we applaud them in their accomplishments in attaining their career goals.” With their academic preparation and training, he feels that BIMS students will continue to become leaders in the medical professions, research fields, government, and industry; he also believes that alumni can play a significant role in determining the future and continued development of a program. “Of course, monetary donations can help support scholarships for deserving students who are short of funds,” Huebner said. “Not only economic support but the volunteering of time or giving in other ways can also help someone else in their pursuit of a quality education.” Huebner expects the BIMS undergraduate program will continue to develop in the future, while maintaining a high standard of education and teaching excellence. ■ Dr. Henry Huebner mentoring a BIMS student

FALL 2018 \\ BIMS MAGAZINE | 13

Hitting the

Right Notes As a BIMS alumna on track to become a physician, Hayley Rogers hopes to make an impact through the art of medicine. Story by Dr. Megan Palsa

A large part of Hayley Rogers’ life, even from a very young age, was music. She played the clarinet in the high school band, in small groups while at Texas A&M, and currently plays in a community band at the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB). She confesses that the experience introduced her to lifelong friends, as well as gave her an opportunity to take on leadership roles. “Unfortunately, clinicals in medical school now keep me from playing my clarinet as much as I would like to,” she said. Medicine, however, is an art in itself and having a background in activities outside of the sciences and humanities has helped Rogers become a more wellrounded individual. “Music transcends the barriers that keep people apart; music is also a huge stress relief for me, helping me cope with the rigor of medical school,” she said. “I am 0 percent athletic—much to the disappointment of my mom (Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences executive associate dean Kenita Rogers), ha ha— but I did do marching band throughout high school. “My closest friend and the person who has made the largest impact on my life outside of my family is my longterm boyfriend,” she said. “We actually met in high school in band!”

Volunteer work

Rogers has a certificate in hospice and palliative care from an extensive volunteering program. She spends time on fundraising opportunities to help local LGBTQI+ organizations with clothes and medical supplies. She is also involved in the Blackwell Osler Student Society and the Big Sib/Lil Sib program at UTMB. “My passion is medicine and helping people through the art of medicine,” Rogers said. “I have always been active in the community, hoping to make a small change 14 | BIMS MAGAZINE // FALL 2018

in the lives of underserved individuals. I was drawn to medicine because of the ability of physicians to make remarkable improvements in the lives of their patients and communities. “There is nothing more precious than the trust a patient shares with their physician. This bond is incredibly important to implementing holistic healthcare, and I hope to work with other providers to incorporate the full identity of the patient into their care,” she said. “It's incredibly important to bridge the historic distrust between the LGBTQI+ population and providers.” Laying a new foundation of trust, according to Rogers, is essential to improving health outcomes in the underserved population. She has long been active in diversity education, so the transition into healthcare education was natural for her. She created an organization called Allies in Medicine, which trains others in culturally competent LGBTQI+ centered healthcare, and through this organization, she hosts a variety of educational events and provides rainbow lapel pins to those who have been trained in an effort to show a more visible representation of support by healthcare staff.

Family ties

Rogers said there is no doubt in her mind that being around a hospital/medical environment at a young age influenced her passion for medicine. “I think the biggest thing I learned from my mom (who also is director of diversity and inclusion at the College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences) is that I can do anything,” Rogers said. “I believe it is really important to see women in medicine and in leadership roles. “(Because of my mom) I never doubted that I could pursue a career in medicine or that I could be a woman in charge,” she said. “She is constantly working hard; if you know her, you know she is anything but lazy. I like to

H AY LEY ROGERS LAT. 30.628 ° N / LONG. 96.3344° W

“The BIMS program allows you to hone in on your interests and gives you classes that actually prepare you for your future career.” - HAYLEY ROGERS

BORN AT ST. JOSEPH’S HOSPITAL IN BRYAN, TEXAS. HAYLEY GREW UP IN COLLEGE STATION AND GRADUATED FROM A&M CONSOLIDATED HIGH SCHOOL AND TEXAS A&M UNIVERSITY. SHE IS CURRENTLY A STUDENT IN MEDICAL SCHOOL AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS MEDICAL BRANCH (UTMB).

think that some of that work ethic has rubbed off on my sister and me. “Our mom has always been supportive and encouraged us to pursue our dreams,” she continued. “Nothing was unrealistic for us, nothing out of reach. This mentality made pursuing medicine not so much as if, but a when.” Sibling rivalry has always been alive and well in the Rogers household. She and her sister, Callie, a second-year veterinary student at Texas A&M, have always been competitive, especially in school. “We didn’t get along well as kids, but now we are very close and have bonded over our shared experience of becoming doctors. We will call each other multiple times a week to de-stress and talk about our lives,” Rogers said. “I know I can always rely on her when I am feeling stressed or overwhelmed because she gets it. I am very excited that we will be Dr. Rogers together.”

Why BIMS

Struggling with a decision between going to Rice and/ or Texas A&M was real for Rogers. She did not take the choice lightly. She scheduled a meeting with Dr. Elizabeth Crouch, the associate dean of undergraduate education in the biomedical science program at Texas A&M, and their conversation helped her to decide that the BIMS program at Texas A&M would be the best choice for her. 16 | BIMS MAGAZINE // FALL 2018

“I knew I wanted to go into a program that had advisers who cared so much about the program that they were willing to meet a high school student to talk them through their decision,” Rogers said. “At that point, I already knew I wanted to pursue a career in medicine, and the BIMS program had a good curriculum that was directed toward this goal.” Rogers said she would tell students that if they want to go to professional school (dental, veterinary, medical, etc.), the BIMS program is ideal. “The BIMS program allows you to hone in on your interests and gives you classes that actually prepare you for your future career,” she said. “Many universities do not offer specific pre-professional majors, and I think this is a major draw to Texas A&M.” She went on to explain that the people in the program are excellent. “The advisers, faculty, and staff are dedicated to making sure you reach your dreams and are successful,” she said. “I received a lot of support within the college, and I know this is part of why I was so successful at Texas A&M. “The curriculum allows you to customize your undergraduate journey to best suit your interests,” Rogers said. “If you are interested in animals, there are lots of electives in animal topics.” This flexibility also allows students to prepare themselves for the future, as well as to have fun with

exciting electives; it was one of those electives that led her to double major in entomology. “The rigor and subject matter of the classes have really helped prepare me for medical school,” Rogers said. “One particular example I have is the anatomy class we took in the BIMS program. In my medical class (at UTMB) all of the students from Texas A&M had a head start in our anatomy lab, since we had already done a mammal dissection; the two classes were very similar, with a lot of overlapping content. I enjoyed the structure of the program, which helped me get my medical school prerequisites, while also allowing me to have diverse elective experiences.”

The ‘grind’ of medical school

Rogers jokes that medical school is like a love-hate relationship—on one hand, she sometimes hates the tests and the constant grind, but on the other hand, she loves working with patients and learning the art of medicine. “I absolutely am sure I made the right decision to go into medicine and I am constantly grateful I have the opportunity to do what I love,” she said. “The rigor and stress of med school has allowed me to make some of the closest friendships I have ever had. The shared experience of going through something this demanding really brings people together.”

Impact on society

Lofty goals about improving society through improved healthcare is a common desire for medical students, according to Rogers. Similarly, she has always wanted to leave a positive impression on others and feels it was her calling to serve others through medicine. She includes herself in the growing number of medical students with the desire to improve healthcare on the institutional side through public policy—and she has worked to do so by being active in the Texas and American Medical Associations— as well as on the local side by helping to relieve the suffering of each of her patients. Through these organizations, she has written and successfully passed several pieces of AMA legislation, including policy on inclusive medical documentation for LGBTQI+ patients and access to public facilities for trans individuals. She was also instrumental in helping UTMB attain status as a leader in LGBTQI+ health care through the Human Equality Index.

She did travel to Qatar on a spring leadership exchange experience through Texas A&M, during which students from Texas A&M at Qatar come to College Station for a week, and she went there for a week with that program. “It was an amazing experience, and my first time abroad,” she said. “In medical school, I am part of the global health track, so I traveled to Peru for six weeks for research and for an intensive field epidemiology course.”

Looking into the future

Identifying students in need of a scholarship and giving back to the BIMS program is one of Rogers’ passions. She has a heartfelt passion for the LGBTQI+ community and students with disabilities and would like to help them succeed. Beyond money, she said that she would love to mentor potential future physicians in their journey to medical school. She finds mentoring rewarding for both parties involved, and she has found several mentors in medical school who have supported her through her journey. She hopes to be able to spend her career in medicine helping others, whether it be through public policy and advocacy or directly through health care of individual patients. Her immediate goal is to graduate from medical school, but her overarching goal is to be happy. “I have spent a really long time in higher education now, and one thing I’ve realized is that the medical field is hard, and I will be constantly challenged, which is something I also really enjoy about the field,” she said. “Because of that, I need to make sure to take care of myself and spend my life doing what I love. I am fortunate that I am able to pursue a career in something that I love.” ■

Bucket list

Also among her goals are having her own dog and travel, which top her “bucket list.” “I haven’t seen much of the world; I really want to see more of it, especially Asia,” Rogers said. “There are so many places and cultures I haven’t seen or experienced. I hope to travel after I match into residency next March.”

The Rogers family with their dog Journey FALL 2018 \\ BIMS MAGAZINE | 17

ALUMNI

Having a Hand

in Healing Alumnus Jason Jennings ’95 has invested in College Station through hard work and dedication that has led from the first Baylor Scott & White hospital in the area to a hospital that offers specialty care. Story by Dr. Megan Palsa

Pictured: (left) Dr. William Rayburn, CMO for the College Station Region, (middle) Jason Jennings, (right) Amber Reed, RN, CNO for the College Station Region

Jason Jennings

hose who know Texas A&M biomedical sciences alumnus Jason D. Jennings will tell you he is a humble man with deep convictions and a passion for helping others to live happy and healthy lives. The chief executive officer (CEO) of Baylor Scott & White Health: College Station region, Jennings directs the day-to-day operations of two hospitals and nine regional clinics in the College Station area and was a critical component in the planning and preparation for the first hospital built in College Station. Baylor Scott & White Health in College Station was a $200 million investment for the community and today has a successful open-heart program, an ICU, a neonatal ICU, neurosurgery, cancer care, endoscopy, 20 | BIMS MAGAZINE // FALL 2018

and specialty services. His hard work and leadership in executing medical strategies in the College Station region is evident in the satisfaction of patients and clients in the community. Prior to becoming the CEO of Baylor Scott & White in College Station, Jennings was the chief operating officer and senior executive vice president for the Hillcrest Health System and Scott & White Healthcare. He has also served as an operations and quality specialist for Tenet Health System, the director of rehabilitation for Bowie Memorial Hospital, the clinical programs coordinator for Good Shepherd Health System, and a practicing physical and senior therapist. In each of these positions, he has helped to expand the capacity of hospitals and clinics, reduce costs, recruit strong employees, and

influence the community in which each hospital functioned. While Jennings has had success throughout his career, he credits the degree from Texas A&M for getting him started in the right direction. After earning his Bachelor of Science degree in biomedical sciences from the College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (CVM), Jennings went on to receive a Master of Science degree in physical therapy from the University of Texas Medical Branch and a Master of Business Administration from the University of Texas at Tyler. “The BIMS degree that I received from Texas A&M provided me the strongest foundation to build upon for both my future education and career advancements,� Jennings said. Jennings also credits many of his professors not only for their teaching but for their compassion for students.

“Many BIMS students cringe at the thought of taking organic chemistry. I took both of my organic chemistries from Professor (John) Hogg, and while the class was extremely difficult, Dr. Hogg’s class taught me about hard work in school, proper balance of priorities, and the joy of achievement after the work is put in,” Jennings said.

Jennings is committed to giving back to his community, including through his membership on the executive council for the American Heart Association and the Wounded Warrior Program, as well as through his volunteering with Mobile Meals, to name a few. He is a guest lecturer at the Texas A&M University Mays Business

School, a previous board member of the Bryan/College Station Chamber of Commerce, a board member with Blinn College, and a proud member of Grace Bible Church. He enjoys hunting, fishing, and playing soccer, as well as spending time with his wife, Jennifer, and daughters, Reagan, who is 16, and Taylor, who is 12. ■

The BIMS degree that I received from Texas A&M provided me the strongest foundation to build upon for both my future education and career advancements.

FALL 2018 \\ BIMS MAGAZINE | 21

ALUMNI

BIMS BOARD FOCUSES ON MENTORSHIP, SCHOLARSHIPS by Jennifer Gauntt

22 | BIMS MAGAZINE // FALL 2018

2018-2019 BIMS Board with Development Staff Members

As the new president of the BIMS Board in the College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (CVM), Mark Vara ’83 and ’87 (DVM), and chief executive officer of the San Antoniobased Vanguard Veterinary Associates, is dedicated to working with and for students in the CVM biomedical sciences program. When the board met for the first time under Vara’s tenure in April, the group “laid the groundwork” to increase mentorship opportunities between board members and BIMS students, as well as scholarship funds for undergraduates. “As we move forward, we want to engage everyone and make this an active board,” Vara said. “We’re going to try to increase our exposure to the students by making ourselves more available to them, including mentoring from our home cities. “We want students to have our contact information, so they can reach us 24/7, every month of the year,” he said. “Different board members will be in College Station at different times, for events like game weekends, but we also want students to reach out to us anywhere in the state; if you’re from Dallas, and (board member) Dr. Steve Ruffner’s in Dallas, and you can get in touch with him. We’re just trying to be a lot more accessible.” Members are also working to take more “ownership” of the board by dividing into committees for mentoring, fundraising, and marketing, as well as by establishing a new mission statement—“To provide support as ambassadors, both financially and through mentorship, to undergraduate students and programs in the College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences.” Part of supporting BIMS students financially includes a fundraising goal

of $3 million over five years, which they hope will help offset the cost of undergraduate education. In the past two years, 16 unique scholarships of $1,000 to $4,000 have been awarded from the BIMS Board. The board also hopes to bring more BIMS students to their quarterly meetings to discuss topics that are of importance to them. The BIMS Board comprises 24 biomedical sciences alumni who are dedicated to supporting the college by working to increase current and former student engagement, student scholarship opportunities, and job and internship placement opportunities. “We (board members) get more enjoyment out of helping the kids than getting any awards, or anything like that,” Vara said. “We’re always looking for alumni to join us. There is a time commitment, and there’s a financial commitment; this is a board that’s very engaged. We want to walk the walk.” ■

If you or someone you know would like more information on being part of the BIMS Board, contact assistant director of development Jordan Kuhn at 317.502.3204 or jkuhn@txamfoundation.com.

FALL 2018 \\ BIMS MAGAZINE | 23

TEACHING

“We give them an opportunity to be creative, and an audience, tools, and training on how to lead a group of people.” - LARRY JOHNSON

As a histology professor and coordinator for the CVM’s Peer Education Program, Dr. Larry Johnson exudes a joy for teaching and mentorship that inspires students’ creativity, emboldens their confidence, and stirs their passion for science. by Kasey Heath

C

olorful drawings, miniature skeletons, and models of the human body fill Dr. Larry Johnson’s office. He displays thank you notes from students on all of his shelves—one with drawings of animal lungs from an elementary school student, one designed in the shape of a microscope from an undergraduate student. These students express the discovery, the joy in learning, and the inspiration Johnson aims to incorporate into his teaching. He reads from them and smiles, visibly moved as he recalls how his students remember him. “The drawings in cards always have me wearing funky ties,” Johnson said. “I am known for my ties, because I wear a different one almost every day.

Students always draw me wearing my histology-themed one.” As principle investigator of PEER, the Partnership for Environmental Education and Rural Health, and professor of histology in the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences (CVM), Johnson empowers and inspires each student he interacts with to become leaders and educators in the various fields of science they go into. In turn, students impact Johnson’s life and help bring joy to his teaching. Johnson leads a team of professionals and students interested in science and public education through the PEER Program, which aims to educate youth about complex science topics in a way that is engaging and relatable.

“We trick the kids into learning,” Johnson said. “They think they are just having fun but they are learning and they don’t even know it. The PEER Program makes biomedical sciences and becoming a veterinarian more accessible than youth would have thought otherwise.” Current veterinary and biomedical sciences (BIMS) students create journals and pamphlets that are based on STEM-related topics for teachers in schools around the country. The materials can be tailored to the teacher’s curriculum and are designed to meet state educational requirements. PEER also provides a weekly educational webcast and creates classic games, such as medicalthemed "Medopoly," that are life science related. FALL 2018 \\ BIMS MAGAZINE | 25

Dr. Larry Johnson displays his thank you notes from his students.

Johnson applauds the creativity of his students. “They design all of these materials themselves,” Johnson said. “I am always amazed by what they produce.” Undergraduate students also help develop lesson plans for teachers who have requested materials through the “Teacher Request Resource” page on the PEER website. Students who are interested in the requested topic develop the materials, which get reviewed by CVM faculty and area teachers before they are implemented in school curriculum. Johnson said when a student has a passion for a given a topic that makes it easy to teach about it. “That’s what elementary and middle school students want,” Johnson said, “somebody who loves their subject. Students want to love a subject as much as the person teaching it.” 26 | BIMS MAGAZINE // FALL 2018

Aside from PEER, Johnson teaches histology (VIBS 243), a veterinary integrative biosciences course for undergraduates and provides experiential learning opportunities. This is possible because the major

They design all of these materials themselves, Johnson said.

I am always amazed by what they produce. instruction for the course is via histology lectures on Johnson's YouTube channel, which has over 10,000 subscribers. This course is unlike any others students take—undergraduates who take the course have a chance to

become teaching assistants (TAs) for the course the following year and subsequent years when they take on more leadership in the TA training. Johnson said the TAs provide mentorship for students currently taking the class, which helps Johnson in his instruction. “TAs put together review sessions before exams, come up with extra credit opportunities and run a help desk to answer questions students may have,” Johnson said. “The TAs come up with these ideas themselves to make the course more effective. A lot of times a student won’t tell an instructor about a problem, but they’ll tell another student. And if there is a problem, I want to fix it if I can.” Johnson said the TAs sometimes provide more insight into the course than he himself can give. “The TAs provide tricks on how to remember terminology and concepts

because they have been through the class before,” Johnson said. “That’s something I would never do, but the TAs tell the students, ‘Let me tell you how I remembered that,’ and it’s much more meaningful. They know how to view it from a fresh and new perspective. High-performing and active VIBS 243 students are asked to be TAs for the following year. TAs gain elective credit, with every credit earned requiring two hours of work toward the course each week, whether through help desk assistance or providing insight at an exam review. Johnson said being a TA or PEER educator provides a unique experience that allows students to gain a variety of skills, from thinking creatively, to leadership, to enhancing

communication skills, and even gaining the confidence they need to educate the public when they graduate, which can be beneficial no matter which biomedical sciencesrelated career field a student selects. “We provide the students with an opportunity they wouldn’t get otherwise,” Johnson said. “We give them an opportunity to be creative, and an audience, tools, and training on how to lead a group of people.” They are skills students cherish; one student expressed how much Johnson inspired her. “She wrote, ‘Dr. J, I loved watching your enjoyment as you spoke with students and I want to be able to do the same thing one day,’” Johnson read. “She said she wanted to feel the same joy of being so passionate.”

Johnson expressed how the PEER program and VIBS course not only educate students, but also empower them to be successful. “The most important thing they can be is a role model,” Johnson said. “This gives them the confidence to educate the public about STEM topics in the future.” Browsing all of his materials, Johnson becomes overwhelmed by emotion, showing how he loves what he does, not because of personal achievement, but because of how successful his students become. His enthusiasm and love for the subject clearly is infectious and the funky ties, a visual representation of the joy he finds in teaching. ■

Dr. J shares with incoming BIMS students a clip from his YouTube channel. FALL 2018 \\ BIMS MAGAZINE | 27

TEACHING

In her “living, outdoor laboratory,” Dr. Alice Blue-McLendon teaches BIMS students the intricacies of working with exotic animals; in turn, her center benefits greatly from the students, who are able to apply those lessons by contributing to the center’s success. by Rachel Hoyle

The Winnie Carter Wildlife Center is a research and teaching facility that houses wild and exotic animals as part of the College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (CVM). Just about a mile from the CVM complex, the daily scene is one from another world: ostriches perform mating dances, a serval lounges in his enclosure, and 100-pound tortoises munch on their veggies. The center was founded in the 1980s by J.D. McCrady, a former head of the CVM’s Department of Veterinary Physiology & Pharmacology (VTPP), who saw the need for a wildlife-exotics animal program. Thanks to him and generous donors—including Winnie Carter, after whom the center is named—students can work with animals from all over the world without leaving the campus. Currently, the center is home to such animals as peacocks, two parrots, ostriches, llamas, emus, desert tortoises, a serval, and the world’s first cloned white-tail deer, Dewey. It is run by Dr. Alice Blue-McLendon, a VTPP clinical associate professor, who is proud of the center’s uniqueness. “It’s very rare to have a program where students can get this kind of experience on the campus without having to travel,” she said. “That’s a huge advantage that we have here at the veterinary school.” One of those advantages is a directed studies class (VTPP 485) through which students can get experience with “cool animals”—as Blue-McLendon calls them—for as many as four hours of course credit. “This experiential learning program is designed to give undergraduate students experience with nondomestic animals,” Blue-McLendon said. “Students help with all aspects of animal husbandry and get some experience with medical procedures and research; it just depends on what’s happening when the students are here.” 28 | BIMS MAGAZINE // FALL 2018

As one of the largest directed study courses offered on campus, VTPP 485 has grown since it was first offered in the 1990s. When the class was inaugurated by BlueMcLendon’s mentor, Dr. Jim Jensen, only six undergraduate students took advantage of the unique experience; today, there are 25-30 registered students per semester. In the “living, outdoor laboratory”—a description coined by Blue-McLendon—students gain hands-on experience through a variety of opportunities, including being responsible for an animal and its enclosure, which allows the student to become familiar with animal-specific care and behaviors; or, as needed, bottle-feeding baby deer or de-antlering an adult deer. At the end of the semester, students are expected to complete a project that promotes animal enrichment, which is an important part of the animal’s overall wellbeing. “When it comes to taking care of animals,” BlueMcLendon said, “it’s far more than just giving the animal food every day; their environment and enrichment is also important. The animals really benefit from the students being here, and students really help us run this facility.” The students also benefit from the mentorship of BlueMcLendon, who gets to know each of them; enjoys helping them make decisions about veterinary school (something she knows a thing or two about as a veterinarian, herself); and keeps them focused on their aspirations. “One of the best things is that I have the pleasure of mentoring students before they get into vet school, and then I see them again in vet school because I teach professional curriculum,” she said. “It’s great to watch people’s careers progress; some of them even become lifelong friends and colleagues of mine.” Although the majority of students who participate in her directed studies class are focused on pre-veterinary

My motto here is that good students never go away Alice Blue-McLendon

studies—Blue-McLendon estimates that these represent about 75 percent—the VTPP 485 program is open to all majors and attracts students with a variety of interests: aspiring zookeepers, animal behaviorists, and even premedical students. This shared interest brings students together to not only work with “cool animals” but also to develop skills for success. “For Wildlife Center students, I see some of the characteristics that are important for helping people be successful: I see a student’s work ethic, motivation, communication skills, and their ability to work as a team more than I would see in any other type of course or lab,” she said. “Some of these ‘soft skills’ are important for success in professional programs, like vet school.” It seems, then, that the labor-intensive nature of the course promotes personal growth as well as the development of good working relationships. Students depend on each other to complete assigned tasks, many of which require multiple sets of human hands. “It is not uncommon for students to become friends, roommates, or even colleagues,” Blue-McLendon said. These added benefits might be among the reasons students return to the center as volunteers after completing the course. “My motto here is that good students never go away,” Blue-McLendon said. “One of our students who graduated in the spring had been here for five semesters. That tells me that they’re having positive experiences here.”

- ALICE BLUE-MCLENDON

Those who come back are given additional responsibilities, such as training and mentoring new students, a benefit to everyone. “Repeat students and volunteers are some of our best assets here; they are really valuable in helping train incoming students,” Blue-McLendon said. “Mentoring is really important for the repeat students—they get leadership skills and empowerment. The students feel that they can really have an influence and make a difference.” ■

FALL 2018 \\ BIMS MAGAZINE | 29

TEACHING

by Jennifer Gauntt, Kasey Heath, & Briley Lambert

Every year,

hundreds of biomedical sciences students journey around the world to learn about other cultures and their medicine,

but what they end up learning the most about is

themselves

.

30 | BIMS MAGAZINE // FALL 2018

Students participating in the 2017 Barcelona Global Health program take a day trip to Sitges, Barcelona, Spain, to learn about architecture and summer residence during the XIX and XX centuries.

Spending several weeks over the summer, or even an entire semester, in an idyllic setting, earning class credits with views that are world-renowned—what could be better? For the hundreds of undergraduates in the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (CVM) who study abroad each year, a semester overseas means more than just coursework. By choosing one of the plethora of biomedical sciences (BIMS) classes held in countries around the world, students bring into focus the concept of global one health, get a hands-on education by working with a country’s population, and, perhaps most importantly for the professors teaching those courses, gain a whole new perspective of the world around them.

“The study abroad experience makes no sense if it isn't transformative for the students, principally, but, frankly, also transformative for the faculty who are engaged; a really good study abroad program changes everyone it touches in ways that we can see and in ways that we can't necessarily see,” said Dr. Jeremy Wasser, an associate professor who has led the study abroad experience in Germany for 15 years. It’s a sentiment echoed not only by the other professors who teach abroad, but also is reflected in the writings students do about their experiences—a rising awareness of the importance of being citizens of the world transcends the course material, proving study abroad isn’t about physiology, environmental health, or veterinary medicine. “It’s really about everything,” Wasser said. FALL 2018 \\ BIMS MAGAZINE | 31

LAT. 9.7489 ° N / LONG. 83.7534° W

COSTA RICA

While in Costa Rica, Texas A&M students get some hands-on experience working with animals.

A major bonus of the program is that students have the opportunity to fulfill 16 credit hours of coursework from the time they land in Costa Rica until the end of the semester.

32 | BIMS MAGAZINE // FALL 2018

‘Waking Up’ in Costa Rica

The classroom takes to the jungles of Central America for BIMS’ Costa Rica study abroad program, where Texas A&M University’s Soltis Center for Research and Education houses students for a unique, semester-long experience. Designed to give upper level pre-medicine, preveterinary medicine, and other pre-health students the chance to learn and travel while keeping up with their rigorous coursework, the program offers a “one health” focus that gives students a holistic core curriculum education in human, animal, and environmental health in the context of Costa Rican and Latin American culture. Associate professor Donald Brightsmith said the combination of these three subject areas, plus the invaluable international experience, gives the students a one-of-a-kind study abroad opportunity. “We really try and create an integrative program across many of the courses,” Brightsmith said. “This study abroad helps fulfill basic core requirements for these students. It’s like being on campus, but with toucans flying by. We hop on a bus and we go on fun and educational excursions.” Formal education is a vital component to the study abroad, but Brightsmith noted how much students get to experience outside of the classroom lectures. “Students have the chance to explore national parks, hike through the rainforest, tour a banana plantation, ride a zip line, swim in hot springs, and ride a trail on horseback,”

Brightsmith said. “We tour a hydroelectric facility and hospitals, medical clinics, and veterinary clinics. There are a variety of educational experiences and fun outings.” A bonus of the program is that students can fulfill 16 credit hours of coursework from the time they land in Costa Rica until the end of the semester. Courses include “One Health and Ecology in the Tropics,” microbiology, genetics, writing, and Spanish communication. Brightsmith said this puts many students at an advantage, because being able to complete a full class schedule while abroad keeps many on track to graduate. “I’ve had more than one student of mine return and tell me they get to graduate early because of the program,” Brightsmith said. “Students also have the opportunity to gain internship and shadowing credits.” In addition, students complete a semester-long research project related to the broad subject of health and how human, animal, and environment challenges overlap in Costa Rica, the United States, and abroad. For the project, students must employ their problem-solving skills to propose a mitigation strategy, or what they think would help reduce the threats from this risk. A large part of the coursework includes the exposure to Spanish culture and language. While the three-weeklong Spanish courses are largely responsible for teaching students the basics of the language, Brightsmith said the majority of the learning and application takes place during the students’ home stays with Costa Rican families. Students in Costa Rica

Students in Costa Rica

“Culture and language are a super important part of the program,” Brightsmith said. “I’ve had people say they’ve learned Spanish more and how to use it better in those three weeks of home stays than they have throughout all of the education they’ve had related to Spanish.” While educational growth takes place, Brightsmith said transformative personal growth also takes place in the students, which is evident in the field journal entries students are required to record throughout the semester. Brightsmith said the journals help document how the cultural and social experiences alter how students think throughout the trip. “Because I read all of these journals, I get to see the evolution of these students, and they change throughout the semester,” Brightsmith said. “In many cases they grow, and I get to track that growth, which is really cool.” Brightsmith said the biggest lesson he hopes students take from this experience is to stop, look around, and truly learn from the people and world around them. “An important mantra for my program is ‘No sleepwalking,’” Brightsmith said. “It is so easy to float through life without really analyzing and learning from what is going on around you. “At the beginning of the semester, many of the students are not really accustomed to thinking critically about where they are and what is going on around them,” he said. “However, by the end of the semester we have a group of students who are keenly aware of both how they are impacting the environment around them and how this environment is impacting them. It is an incredible to watch this transformation.” ■ FALL 2018 \\ BIMS MAGAZINE | 33

LAT. 51.1657 ° N / LONG. 10.4515° E

GERMANY

Students in Germany

Taking a ‘Hero’s Journey’ in Germany Alexa Mendoza rides a bike on the island of Norderney, Germany, during a semester abroad.

“Our job has been to create programs that give students this extra something, an opportunity for transformation that makes investing in a study abroad worth taking the chance.”

34 | BIMS MAGAZINE // FALL 2018

“How is the coursework different? Why is it different? Why not just teach the students on campus?” Associate professor Jeremy Wasser responds to those questions frequently in regards to study abroad programs. “Transformation,” Wasser said. “Our job has been to create programs that give students this extra something, an opportunity for transformation that makes investing in a study abroad worth taking the chance.” Wasser directs the Germany Biosciences Semester in Bonn, the longest-running, semester-long program in the CVM, designed for biomedical sciences, life sciences, and biomedical engineering majors. More than 500 students have traveled to Germany with Wasser since 2004, including 147 who have participated in the semester abroad. Wasser attributes the program’s success to its ability to motivate change in everyone in the program, from the students to the faculty, and even the German hosts. The program’s high-impact coursework was designed with this in mind. Students work toward general education credits-typically a 13- to 14-credit-hour course loadduring the program. All students take the “History of Medicine” course with Wasser; the remaining credits are major-specific, including physiology and genetics for BIMS students and circuit analysis and device design for bioengineering majors. Students also get opportunities that cannot be experienced in a classroom. One such example is the collaborative project with the German Biotech company enmodes GmbH, which manufactures medical technology,

actually change a student’s world view. “This is about giving the students an opportunity to realize there are multiple ways to do things,” Fait said. “Not everything we do is always right and we can all learn from each other.” As part of the “History of Medicine” curriculum, students learn about neurophysiology and music with lecturer Micah Waltz. Waltz said his lessons begin with neural circuitry basics and expand into teachings about the auditory system as a whole; he teaches how the brain processes sound and produces an emotional response to music, and even about the political and historical context of music. (READ MORE

ABOUT WALTZ’S “NEUROPHYSIOLOGY OF MUSIC” CLASS ON PAGE 62.)

specializing in cardiac and pulmonary devices such as total artificial hearts and lungs. The company presents students with a project employees are currently working on and the students work together to create a solution for the problem. At the end of the project, the student group pitches that solution. Wasser said the diverse group dynamic of bioengineering and BIMS students creates a unique environment for a real- life project pitch. “enmodes is a particularly good match for us because they love the two different groups in this project,” Wasser said. “The company never said the biomedical sciences or bioengineering students don't have the skills to contribute; they actually say, ‘We want them involved in this.’” Wasser said the project teaches students more about themselves than about technical concepts. “They’re not just learning physiology and engineering, but how to work together, how to work at the interface of disciplines, how to design and be creative, and the pains and pleasures of creative work,” Wasser said. “They come away with incredible confidence. You have to teach them; you have to show them they’re capable.” Students also gain an international perspective on pharmacology through a course taught by clinical professor Virginia Fait, who devotes lectures to the differences between the U.S. and German medical systems, including in drug approval, how each country treats psychological conditions, and what one can buy at a pharmacy in Germany but not the United States, or vice versa. Fait said this course does more than just inform—it can