6 minute read

3. ANALYSING EXISTING AND PROPOSED SOLUTIONS

from Preserving Vanua

Analysing existing and proposed solutions:

Identifying the current actors - Fiji cluster system and partner organisations:

Advertisement

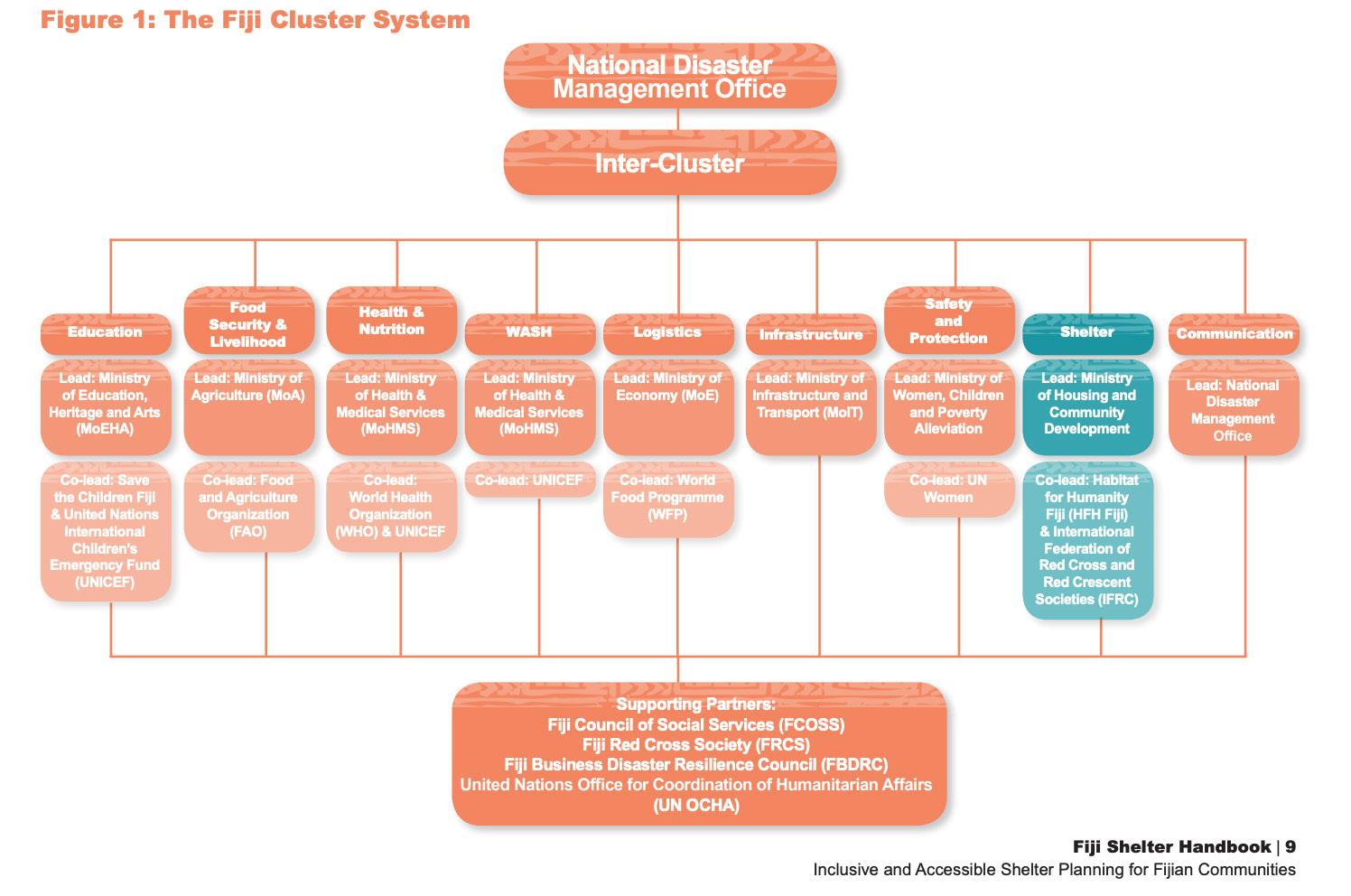

There is a well-established network of actors responding to the growing problems in Fiji. The Fiji Cluster System (Fig 3) has been in operation since 2011, with the National Disaster Management Office (NDMO) overseeing the coordination of all national-level disasterresponse programmes (Shelter Cluster Fiji, 2019). The Shelter Cluster is led by the Ministry of Housing and Community Development while Habitat for Humanity Fiji and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies act as co-leads.

Fig 6: The Fiji Cluster System highlighting where the Shelter Cluster fits in (Shelter Cluster Fiji, 2019)

What steps are currently taken before resorting to relocation?

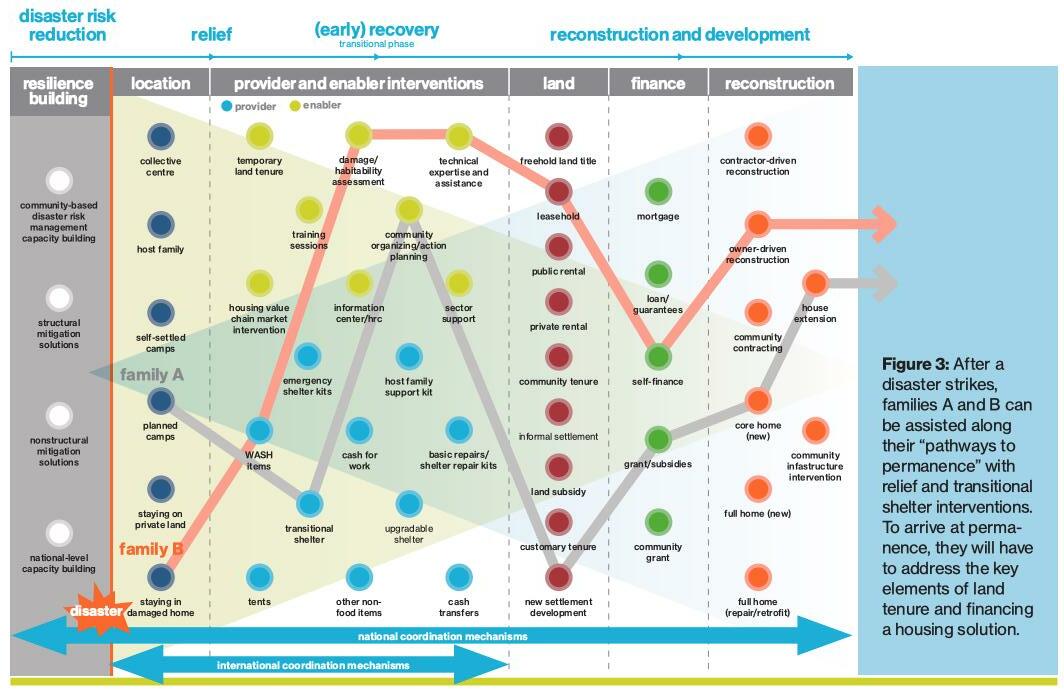

It is widely acknowledged by all the actors, that relocation should be the last resort, only to be carried out after all other feasible adaptation options have been explored (COP23, 2018). For this reason, there are a number of alternative programmes being developed in Fiji to address the displacement of communities as well as reduce their vulnerability to future hazards, such as mangrove rehabilitation, sea wall construction (Chaudhury, 2019) and shelter reinforcements, for which Habitat for Humanity are a key actor. Although they have executed a few relocations since their conception 30 years ago, Habitat’s main focus lies in the reconstruction of existing and new houses on current land as well as training and capacity building for communities with the belief that “sustainability comes in when people have the capacity to rebuild themselves” (Latianara, 2021). Rather than prescribing specific shelter solutions, they recognise that there is a range of roles that may take up at different stages of the process. Together with the Inter-Agency Standing Committee Shelter Cluster, they have been operating what is the known as the ‘Pathways to Permanence’ in countries around the world. This concept aims to provide disaster-affected communities with stepping stones to achieve permanent shelter solutions through the use of “holistic program interventions” (Habitat, n.d.) and is based on the idea that “safe, decent shelter provides the platform upon which much of post-disaster assistance [such as health, water, sanitation, livelihoods etc] is built” (Shelter Cluster Fiji, 2019:18) (Fig 4). Though no two pathways are exactly the same as they are heavily influenced by the context, Fig 4 illustrates a general potential pathway for communities that want to stay in their existing site, showing that there are still steps that can be taken to ensure their future safety, without the need for relocation. However, with the increasing frequency of disasters in Fiji, the rate of reconstruction could be too slow to ensure households are protected against the next hazard. For this reason, there is a need for more holistic resilience and reduction programmes that look at strengthening whole land strategies rather than just at the individual household level.

Fig 7: The Pathways to Permanence illustration (Habitat, n.d.)

It is also crucial to recognise and integrate the strengths of Fijian heritage. In an interview with Masi, the national director at Habitat for Humanity Fiji, he laments that the traditional Bure dwelling (Fig 7), “which has gone through centuries of environmental testing, is all but lost” (Latianara, 2021). In fact, today, it makes up just 3% of the overall housing stock (Shelter Cluster Fiji, 2019). This is primarily as a result of colonial and Western influence on Fijian housing technology resulting in a desire for ‘contemporary and modern’ style houses, that are not as resilient against the hazards in Fiji (Latianara, 2021). However, Masi explains that rather than building these houses themselves, Habitat for Humanity are working with local builders to help them recognise the value of their traditional construction with the belief that the revival of their vernacular will come automatically once it is seen as desirable (ibid.). It is important to note here that the revival of old Fijian construction techniques, for which mangroves and other timbers are often used, needs to occur alongside mangrove planting and rehabilitation to ensure that it is sustainable and does not exacerbate deforestation.

(Singh et al., 2020:12)

When relocation is the only option, how can place attachment be maintained?

Keeping existing physical and emotional ties with land is difficult in a process where communities are physically moving their entire settlements. However, there are some ways to mitigate the loss, at least to some extent. Where possible, the new site should be located within the customary boundaries of their own clan’s land. This can help to keep their ties to the land intact, as well as avoiding land ownership issues (Singh et al., 2020). However, with growing displacement, this may not always be an option. In this case, it is crucial to facilitate discussions about land rights and compensation between the relocating community and the host community right from the start of the process (McNamara and Des Combes, 2015).

The Vunidogoloa community was relocated within their own territory but the move was still an “emotionally disturbing experience” (Singh et al., 2020:11) for some. However, there were a few techniques that were used to mitigate the loss of place attachment. One such strategy was engaging with the community throughout the process. This lead to them supplying the timber for housing construction from their customary lands. Not only did this provide a physical tie to their vanua but it was also sustainable and helped to reduce the cost of the relocation (McNamara and Des Combes, 2015).

Integrating shelter and ecosystem-based adaptation strategies for disaster risk reduction

Although there is vast research on both of these topics separately, there is very little on examples and benefits of integrating shelter strategies with EBA systems such as mangrove planting, permaculture and intercropping (Singh et al., 2020). Masi states that while the two sectors are very much related, they often do not collaborate because the cost associated with both housing and “this kind of protected remedial infrastructure” is so high that funding streams don’t deal with them together (Latianara, 2021).

However, enhancing the resilience of the land on which settlements will be placed seems like it would have its benefits. One example of where this strategy has been used is ACTED’s programme to support flood-affected families in Pakistan in 2012 through the integration of disaster risk reduction, shelter and food security inspired by permaculture practices. Through cross-sectoral collaborations with WASH and the Nutrition cluster, they were able to come up with innovative ways to mitigate sanitation risks by planting trees that absorb the surplus waste-water, plant trees as windbreaks for shelter protection as well as households’ vegetable gardens and create new livelihood opportunities (ACTED, 2012). Although the information on the success of this project is limited, there has been a lot of emerging data on the benefits of permaculture in increasing the strength of soil and the resilience of crops and farms during storms. It would certainly be interesting to see whether it can be integrated within shelter and settlement design to create resilient self-reliant communities.

(Singh et al., 2020:14)