33 minute read

faculty focuS: dR. allan nelSon

Health, Human Services college appoints first Dean

Dr. Vimala Pillari was selected dean of Tarleton’s new College of Health Sciences and Human Services following a national search. The new College of Health Sciences and Human Services opens this fall to better serve the 1,600 students already enrolled in successful, established programs in medical lab sciences, public health, social work, counseling and nursing. Programs are offered in Fort Worth, Waco and Midlothian as well as at Tarleton’s Stephenville campus and via its online Global Campus.

Pillari earned her bachelor’s in home science/economics, child psychology and sociology and her master’s of social work—with a specialization in families and children—from Madras University in India. She received her doctorate in social welfare from Columbia University in New York.

Sandi McDermott appointed to state yMCA advisory board

Dr. Sandi McDermott, director of Tarleton’s center on the Navarro College Midlothian campus, was appointed to the advisory board of the Texas State Alliance of YMCAs.

The alliance aims to improve nutrition and physical activity standards for licensed out-of-school time (OST) programs in Texas.

A board member of the YMCA of Metropolitan Fort Worth, McDermott has a doctorate in nursing practice from Texas Christian University and master’s and bachelor’s degrees in nursing from the University of Texas at Arlington.

She began her nursing career as a doctor’s assistant and has worked for Baylor Health Care System as well as Texas Health Resources and Hospital Corporation of America (HCA), where she helped open neuro-oncology and cardiovascular care units.

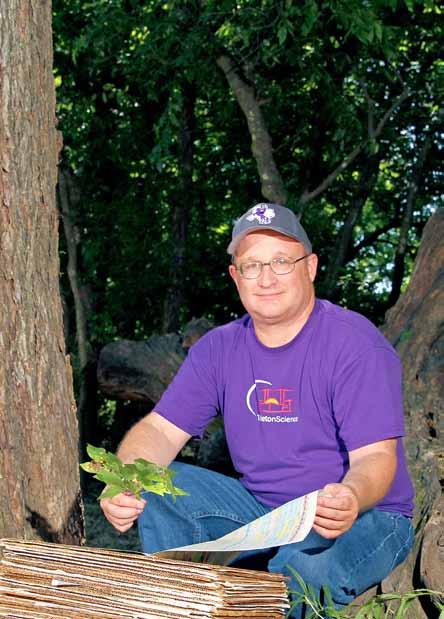

Faculty Focus Blooming where planted

Faculty member combines love of plants, teaching and research to give students the ultimate experience

b y M A ry g . S A lTA r E lli

Alifelong bond blossomed between snapdragons and Tarleton professor Allan Nelson during his graduate studies in plant taxonomy at the University of Oklahoma, where he focused on the genus Chelone, commonly known as turtlehead. Today, Dr. Nelson is a professor and department head of Biological Sciences and works with snapdragon species like paintbrushes and penstemons that flourish in Texas’ Western Cross Timbers area.

“My kinship with snapdragons is so strong that it’s almost as if they’re my children and I want to protect them,” Nelson said. “When I discover a turtlehead in a pristine wetland, I know that no one else may have ever seen it, and it’s amazing it’s there, cleaning the water, providing nectar for bees and supplying food for butterfly larvae.”

The botanist’s passion shows. During his doctoral research, Nelson discovered turtleheads in just 10 percent of the locations where they were previously documented, mostly because the flower’s native wetlands are disappearing.

He leads field studies regularly, such as guiding student research documenting the distribution of Comanche Peak prairie clover, which is endemic to just eight counties in North Central Texas.

“I try to involve students in everything I do,” Nelson said. “Research and teaching go together—you learn during research. Since graduate studies, I’ve never conducted a research project that didn’t involve my students.”

A Tarleton alumnus, Nelson returned 18 years ago to the Western Cross Timbers ecosystem of Texas, where he was born, to share his zeal for flora and fauna with today’s Tarleton students. “Because I grew up here, I have an attachment to the pristine natural areas of the Cross Timbers,” Nelson said. “The Plains, Piney Woods, and Edwards Plateau come together here, giving it elements of all three.”

This summer, Nelson will meet with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service officials to discuss his research with students on the

Texas Kangaroo Rat. Native to Texas’ Northern Plains, the rats with long tails burrow underground, stow away collected seeds and support ants and other organisms. Kangaroo rats are “threatened” in Texas, and Nelson will participate in discussions regarding their national classification.

Most recently, Nelson and his students documented the native vegetation in Texas bottomlands, including along the Bosque and Colorado rivers. Their research took place at the 790-acre Timberlake Ranch near Goldthwaite, which Marilynn and Dr. Lamar Johanson donated to Tarleton.

In addition to recording and collecting plants in the bottomlands, Nelson and his students documented the diversity and richness within the woody forest and the consumption of plants by mammals.

The results of documentation by Nelson and his students along the Colorado River expanded the number of recorded plant species and varieties in Mills County by 49. Nelson and a coauthor are compiling a scientific paper that has been accepted for publication by the Texas Journal of Science. They presented their findings at three conferences, including the 2014 Texas Plant Conservation Conference.

Research is also an important learning tool in Nelson’s biology classes, where he uses what students have seen in the laboratory to bring a topic to life through interactive classroom discussions rather than lectures.

“Students have to learn their subject thoroughly to be able to think about it in an advanced way,” Nelson said. “My goal is to transform my students into professionals who go to work in their chosen field, where scientific skills they learned at Tarleton will help them.”

Dean named for Agricultural, Environmental Sciences college

Dr. W. Stephen (Steve) Damron was selected as dean of the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences following a national search. Prior to being selected, he was the assistant dean of academic programs for Oklahoma State University’s College of Agricultural Sciences & Natural Resources.

In addition to teaching, Damron wrote the book on animal science. In its fifth edition, Damron’s textbook—Introduction to Animal Science: Global, Biological, Social and Industry Perspectives—is used extensively in the U.S. and abroad.

In his new role as dean of Tarleton’s College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, Damron will oversee one of the 25 largest programs in the nation, with 1,900 students. Tarleton operates the only university dairy in the state and is home to one of only two four-year vet tech programs in Texas.

Damron earned his bachelor’s in agricultural science from the University of Tennessee at Martin and his master’s degree and doctorate in ruminant nutrition from the University of Tennessee at Knoxville. During his career, he has received 26 teaching and advising awards and recognitions.

Dr. Thomas Faulkenberry, assistant professor of psychology, was appointed Associate Editor for the Journal of Psychological Inquiry (JPI), devoted to highlighting undergraduate research in psychology.

Published by the Department of Psychology at Fort Hays State University in Hays, Kan., JPI is one of the few journals to accept contributions from undergraduate students, including scholarly work that encompasses a broad range of investigation, literature reviews and historical articles covering any topical area in the psychological sciences.

Faulkenberry joined the faculty of Tarleton’s College of Education in the Department of Psychological Sciences in fall 2013. He holds a bachelor’s in mathematics from Southeastern Oklahoma State University, a master’s in mathematics from Oklahoma State University and a doctorate in psychology from Texas A&M UniversityCommerce.

Tarleton faculty member teaches students a new way to farm

b y C HA n D r A An D r E w

By 2050, the world likely will have 9 billion people—2 billion more mouths to feed. Farmers and ranchers will need to provide substantially more food using the same or fewer resources (water and land) than today.

The challenge of feeding the world of tomorrow is monumental, but one that Tarleton’s College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences is meeting head on.

“We have been tasked to create sustainable methods of food and fiber production that also have minimal inputs and waste products associated with it,” said Dr. Hennen Cummings, associate professor in Wildlife, Sustainability and Ecosystem Sciences. “The Hydrotron epitomizes that mission.”

Tarleton’s Aquaponics Hydrotron is a combination of aquaculture and hydroponic systems. “Aquaculture is farming aquatic animals like fish and shrimp,” Cummings said. “Hydroponics is growing plants without soil using nutrient solutions. Aquaponics blends aquaculture and hydroponics in a recirculating loop.” In 2015, Cummings converted the University Agricultural Center’s greenhouse into a combined greenhouse, aquaponics and hydroponics facility. The Hydrotron now serves multiple purposes, which include research, teaching and the farming of plants and fish. Students first approached Cummings about aquaponics. Cummings researched what would be required to set up the Hydrotron, and designed a problems course for students wanting to learn about hydroponics and aquaponics. “Fewer students are choosing a career in agriculture,” Cummings said. “Aquaponics does not require large acreage or even fertile or level soil. So it may be a way to attract a new generation to agriculture because of its lower start-up costs and fewer land requirements.” The United States has a huge demand for food produced locally and aquaponics has a much quicker turnaround for produce than traditional agriculture, with some plants taking only 40 days to reach maturity while using substantially less water. From Tank to Table

Dr. Hennen Cummings works with a student at the Aquaponics Hydrotron.

6

“I want someone to walk into the Hydrotron and think, ‘I can do this’,” Cummings said. “I want them to think, ‘I can live in the city and be a producer.’ Now food doesn’t have to travel far, and it is going to be super fresh and without pesticides.”

When guests step into the Hydrotron, they are met with the smell of thriving plants, the sight of lettuce on white “rafts” floating on large water tanks and the soothing sound of moving water.

The Hydrotron has six oversized water tanks. Three tanks are set in a shaded portion of the greenhouse and each contains a different type of fish—catfish, tilapia and tiger prawns. The remaining tanks are used to grow plants. A filtration system separates the fish solid waste, which can be added to the prawn tank, and prepares the fish water for the plants.

“The entire system starts with the fish,” Cummings explained. “Aquaponics uses ammonia from the fish to fertilize the plants, and the plants clean the fish water in a recirculating loop. Tilapia will eat plant roots, so they are kept out of the plant tanks. The system’s main inputs are fish food, chelated iron and rainwater.”

After solids are filtered from the fish water, the water flows by gravity to the tanks where rafts support various lettuce varieties whose roots thrive in the fish water. However, fruitbearing plants are grown using hydroponics.

“The fish water does not have nutrients in high enough concentrations to grow fruiting plants well,” Cummings explained. “That is why we use hydroponics and vertical farming to grow tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers and strawberries. But herbs are grown in hanging baskets using fish water.”

to Table

Due to the unique nature of the system, any unusable waste, like plant trimmings, is shredded and composted.

“Everything is used,” Cummings said. “If it can’t be used in the Hydrotron, I am able to use it elsewhere on the farm.”

The Hydrotron exposes students to a different type of farming that may be one of the best solutions in meeting the world’s future food supply needs.

“Fish are more efficient at converting food to body weight than other farm animals like cattle, sheep or pigs since fish are cold blooded and buoyant,” Cummings said. “Roughly 1.1 to 1.5 pounds of feed create 1 pound of fish body weight.”

Cummings and his students also developed a smaller aquaponics system for backyard use. The smaller setups use mainly repurposed materials and are ideal for someone to use on a small scale. The root medium is the fish filter, and fruiting plants can be grown in this system.

“I hold information sessions to explain aquaponics and hydroponics to groups,” Cummings said. “We also will help people get their own systems started or point them in the right direction.”

As a problems course, the Hydrotron forces students to solve real agricultural issues.

“We had an issue with spider mites that came in with the strawberries,” Cummings said. “We also had aphids. Because we can only treat plants using solutions that are not harmful to the fish, we introduced ladybugs and predatory mites as well as praying mantis egg cases and lacewing eggs, and their control of pests was unbelievably successful. Everything we do has to be safe for the fish, or else it destroys the entire system.”

One problem that is turning into a major research project is how to remove snails that were accidentally introduced to the system.

However if Cummings and his students solve Tarleton’s snail problem with redear sunfish (shellcrackers) or prawns, it will benefit the industry as a whole.

The fruits of the students’ labor are already paying off. At the close of the semester, the class had homegrown fish tacos using all the items harvested from the Hydrotron. Periodically, produce is also offered to the public.

“Aquaponics is how we are going to feed the world tomorrow, and many Texans are wanting this fresh, healthy, organic, locally produced food today,” Cummings said. “If I were to open an aquaponics store to sell produce and fish to the public, I would call it Future Food. I would sell a salad with so many different tasting and looking lettuces that you would not want salad dressing. That is the potential for aquaponics to have on our food system.”

As a young boy growing up in Texarkana, James Gentry suffered a head injury while roughhousing with friends. Doctors could not be certain the accident led to learning disabilities but, in kindergarten, James could not spell his name. He shortened it to Jim, which he spelled “Mij.”

Jim did not like school and was a poor speller. Writing tormented him because he could not tell left from right. When Jim was 6, doctors diagnosed him as dyslexic with learning disabilities.

“Back in the ’70s no one knew what dyslexia was,” Jim said. “My mother asked if it was contagious.”

Forty years later, Dr. Jim Gentry, associate professor of Curriculum and Instruction in Tarleton’s College of Education, can laugh at the relative lack of knowledge about dyslexia then versus now. But after he was diagnosed, Gentry got help from a new breed of educators— special education teachers—created by a new public law. He received an educational curriculum tailored to his needs.

B A C DE F G H I J K L N M O P Q R STUV W X YZ

Turning a diSAbiliTy into AbiliTy

He went on to graduate from college, receive his master’s in special education and then a doctorate in curriculum and education, both with a 4.0 GPA. Now an “educator of educators,” Gentry’s research investigates the impact of technologies assisting students with special learning needs.

“The truth is all people have special learning needs,” said Gentry, who co-chairs Tarleton’s Diversity, Access and Disability Services Committee.

“Some simply aren’t as pronounced as others. That’s where good teachers make all the difference in the world.”

When students register with the Center for Access and Academic

Testing (CAAT) as an individual with a disability, they attend an “intake” meeting with Trina Geye, director of Academic Support Centers at

Tarleton, to discuss their needs. Geye said most students at Tarleton who self-identify as dyslexic were diagnosed in second or third grade and many don’t view dyslexia as a negative thing.

“It’s not as much of a stigma,” she said.

Tarleton is “well-equipped” to help students, thanks to increased awareness and technology such as screen readers that read aloud text on computer screens and new apps to assist students with everything from accessing the internet to doing math calculations. The most common view of dyslexia is that it causes people

8to misspell words, placing letters in reverse order, but dyslexia manifests itself differently in different people. The main symptom is trouble in reading, although a cluster of symptoms can occur. Dyslexia often co-exists with related issues such as attention deficit hyperactive disorders and issues with handwriting and math.

The causes of dyslexia usually are genetic, but trauma dyslexia also can result from a brain injury. Since it’s a hidden disability, the International Dyslexia Association estimates dyslexia often goes undiagnosed and affects 15 to 20 percent of the population.

Dyslexia is not tied to IQ. Albert Einstein had an estimated IQ of 160 and was dyslexic. Other famous people with dyslexia include inventors Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Edison; actors and performers Whoopi Goldberg, Orlando Bloom and Jay Leno; entrepreneur Charles Schwab; writer John Irving; and director Steven Spielberg.

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and related state legislation call for universities to make accommodations for students with dyslexia. Accommodations may include: • Fifty percent additional time on timed exams and assignments when speed is not a factor. The extra time does not apply to assignments done on the student’s own time or include extension of deadlines.

• Alternative format text. • Assistance in ensuring an accurate record of class meetings (such as early access to presentation materials, permission to audio record, access to another student’s notes). • Using a reader during testing and screen reading software, if possible.

Students with dyslexia have found a nurturing learning environment at Tarleton.

“I have heard anecdotally that students with learning disabilities are attracted to Tarleton because we provide good services,” Geye said.

Jericha Hopson, a graduate student who works as an academic support assistant in the CAAT, has thrived at Tarleton despite having dyslexia. An Honors College student, she graduated from Tarleton in 2014 with an agricultural education degree and a 3.86 GPA. She is pursuing a master’s degree in agricultural and consumer resources with a focus on education.

Hopson said she worried teachers at Tarleton would not want to help her, but she found a wealth of resources. She had never heard of a screen reader, for example, a tool she now relies on.

“Just finding out there are resources and being able to get to those resources helped me a lot,” Hopson said.

Even something as simple as a text font can make a difference, too. Hopson said she finds it much easier to read a letter in a serif font, which has the “foot” at the bottom of a letter, than a sans serif one.

Gentry said such “visual cues” also helped him learn to read from left to right, for example. He lined up the holes of his notebook paper with the windows of his first-grade classroom.

For the 25th anniversary of the ADA last year, Gentry wrote “I Am Jim” for The Conversation, an independent news source from the academic and research community. The Houston Chronicle and other publications ran it as well. Gentry received an outpouring of support and comments from readers, many of whom were dyslexic or had children with learning disabilities.

“Disabilities could have defined me as a person, but my disabilities are not me,” he wrote in his piece. “I am not dyslexic or learning disabled. I am Jim….”

Gentry sees himself as having a distinctive ability rather than a disability.

“I have a purpose. I belong. I am a teacher at Tarleton State University. I am Jim,” he wrote. “This is what I think when I reflect on the Americans with Disabilities Act. It gives me and others like me the chance to be ourselves and to thrive.”

That, he added, “makes all the difference in the world.”

To read Dr. Gentry’s “I am Jim” piece for The Conversation, visit tinyurl.com/jimgentry.

Dr. Jim Gentry, associate professor of Curriculum and Instruction at Tarleton

The Maker Spot

Much more than a print lab.

b y C EC ili A J AC ob S

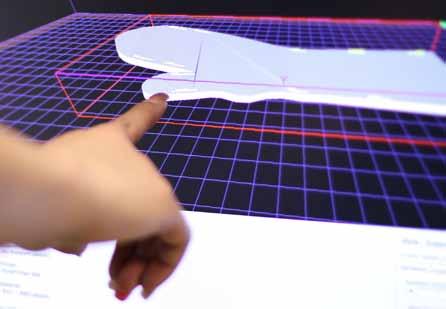

If you can imagine it, you can make it. Even something as ingenious as a customized orthotic for a stroke patient.

Thanks to the new Maker Spot on the upper level of Tarleton’s Dick Smith Library, Clarence Young is getting a specially designed brace for his right hand. It will help stretch his fingers during personalized workouts at the university’s Lab for Wellness and Motor Behavior.

Tarleton senior Christina Tocquigny volunteered to tackle the project as a hands-on learning experience after an appeal was made to Professor Knut Hybinette’s art class earlier this year.

A digital media studies major from Moran, Texas, Tocquigny has a heart for individuals with physical disabilities and understands the enduring relationship of art, science and technology.

“Think Leonardo da Vinci,” Tocquigny explained. “An artist and scientist, he studied physiology and anatomy to create convincing images of the human form. Combining my artistic and creative talents with what I’ve learned in the classroom and the technology now available at the Maker Spot brings the best of all worlds together to help someone in need.”

When the Maker Spot went live this past spring, library officials had a good idea students, faculty, staff—even community patrons—would use the 3-D equipment, poster-size printer, action cameras and invention kits to create everything from keychains to custom-made, alphabet-soup keyboards. But no one figured on a well-fitted device to make life better for a longtime Stephenville plumber.

“The Maker Spot is much more than a print lab,” said Chris Grantham, a technology support specialist at the library. “It allows inventors to turn thoughts and ideas into useable products and prototypes. Maker Spot capability is limited strictly by imagination.”

Spend an hour or two with Grantham and Systems Librarian Margie Maxfield and you’ll see why.

The larger of the two 3-D printers produces “plastic” items up to 9 inches by 9 inches by 20 inches—like a 14-inch propeller for a model airplane. The smaller printer handles projects 9 inches by 9 inches by 9 inches. Specialized websites provide ready-to-use designs, and others allow Maker Spot users to create their own models to print.

The cost to print a 3-D project in any of 16 available colors is 10 cents per gram of filament—a plastic called ABS made from petroleum (like LEGO® sets).

A stationary 3-D scanner copies projects up to 8 inches, and a handheld scanner can replicate life-size models. Imagine scanning a real-live bride and groom to create a cake topper.

When Tarleton’s Community Relations Director James Lehr couldn’t find period-authentic switch plates for his historic home, he asked Maxfield if Maker Spot technology could be the solution. Maxfield used the 3-D scanner

The Maker Spot

to copy one of the few plates James had and, after dozens of tiny adjustments, created replacements identical to the original.

“Although we’re always happy to help tweak designs and give advice where we’re able, library staff generally don’t create models for projects,” Maxfield said. “This was a special undertaking to become familiar with the Maker Spot’s 3-D equipment and test its capabilities.”

A large-format paper printer is available to create posters—everything from family photos to maps to personal artwork—up to 3 feet wide. Cost is $2 per square foot of paper used.

“During spring break, GoPro cameras went like hotcakes,” Grantham said. “Students checked out the water-resistant devices to capture everything from skiing to mountain climbing.”

The Dick Smith Maker Spot also is home to electronic kits to turn bananas into a piano keyboard or set of bongo drums as well as LEGO® sets to create robotics—all available for checkout to reinforce classroom learning and empower students to create, build and produce.

“While several Tarleton departments have equipment and technology similar to what’s available in the Maker Spot, they’re restricted to use by students enrolled in specific labs and classes,” Maxfield explained. “The Maker Spot is open to the entire university as well as community patrons, like local scouting groups.

“Community involvement is one of the best things about the Maker Spot,” she said. “The Maker Spot is an ideal platform for participatory learning communities formed around passions and shared interests.”

According to Maxfield, libraries are evolving from reading rooms and computer labs to dynamic workshop spaces for creative multimedia learning and doing. Because of spaces like the Maker Spot, students are turning classroom knowledge into projects that make the world a better place.

Just ask Clarence Young.

Breaking fromSpring Tradition Members of Tarleton Serves gather on the front steps of Debra Montgomery’s (front, center) home where the student volunteers labored for three days during their Alternative Spring Break trip to repair damages caused by the October 2015 floods that ravaged Columbia, South Carolina.

Student-led ‘Alternative Spring Break’ trip provides perspective, opportunities for service

b y K U rT Mogony E

For a typical Tarleton student, spring break may provide a relaxing reprieve from studying, an opportunity to catch up on some sleep or an escape to a sandy beach or ski slope. For one group of Tarleton students, Spring Break meant service to a community ravaged by floods.

This past March, 22 Tarleton Serves students chose a 22-hour, 1,200-mile bus ride to Columbia, South Carolina, to volunteer as part of the annual Alternative Spring Break (ASB) trip. The Tarleton volunteers joined more than 100 students from four other universities intent on helping residents of the area hit by torrential rain and flooding in October 2015.

Residents are still picking up the pieces and rebuilding their lives. Among them is Debra Montgomery, a disabled, elderly widow, whose modest two-bedroom home was damaged in the heavy downpours, leaving mold and a rotting framework. Repeated applications for FEMA assistance were denied.

For three days, Tarleton students labored at Montgomery’s home, removing rotten window frames and mold-infested sheetrock; scraping decades-old layers of paint and repainting the trim and sills; tidying the small fenced-in yard by trimming and weeding before planting a patch of purple flowers beneath the towering South Carolina pines and magnolias.

Shy and reserved at first, Ms. Debra welcomed the Tarleton Alternative Spring Breakers who were eager to carry out their fourth service project in as many years. While some students brought their carpentry skills to give Ms. Debra’s home new life, others visited with the quiet woman, laughing with her as she reminisced over old family photos pulled from her attic.

On day three, as the students traded hugs with their new friend before boarding the bus and waving goodbye from the windows, the elderly flood victim beamed with pride as she stood in the street and gazed at her freshly painted home.

“I’m a giver, (so) it’s hard for me to receive things from people,” Ms. Debra said. “I feel blessed because they came all the way from Texas to help me.”

Some students shed tears, knowing the difference they made in one person’s life; others promised to write Ms. Debra in coming weeks and to sign up for next year’s spring break service trip—eager to give back again to complete strangers in their time of need.

Organized by the Office of Student Engagement, Tarleton’s ASB provides opportunities for dozens of undergraduates to travel—at their own expense—and work on more than just a tan. The trips foster meaningful student development through service projects that nurture community engagement and give Tarleton students a unique, hands-on education in giving back.

In past years, Tarleton ASB volunteers partnered with Habitat for Humanity to finish new homes for those living in poverty in Albany, Georgia, helped rebuild a flood and mudslidedamaged community in Boulder, Colorado, and aided families affected by Hurricane Katrina in Biloxi, Mississippi.

Steve Lawless, volunteer coordinator from CCI, the non-profit organization that supplied the logistics and arranged Tarleton student accommodations at a nearby church camp on the shores of Lake Marion, said he feels lucky to be part of this important ASB work.

A teacher for nearly 30 years, Lawless observed “the transformational learning that these volunteers experience in the course of a week. How they step out of their comfort zones and face something that might be new to them...is really pretty amazing.”

Several students, including senior interdisciplinary studies major Haile Hall, have participated in several ASB trips. This spring break, Hall was the Tarleton Serves president and helped coordinate the effort and weeklong journey to South Carolina.

“A lot of friends say, ‘you gave up your spring break to serve others?’ But everyone who goes on this trip isn’t giving anything up, and we don’t feel like we’re missing out,” said Hall. “Going on this trip for three years has taught me leadership, selflessness, and it’s a really humbling experience because you take all of that back home with you and you can appreciate more.”

Hall said that Ms. Debra’s sweet, positive attitude facing hardship after hardship in her life made their time together even more valuable.

“She couldn’t believe we were spending our spring break helping her… we were still all-hands-on-deck as we worked to repair her home,” Hall said.

“She taught us that you can have an impact on others, and that you may experience a low but there’s always someone experiencing a lower point in life. Everyone needs a helping hand at some time in their life, and we just happened to be there for her.”

Upon returning to Stephenville, Hall and others penned letters to Ms. Debra thanking her for allowing them to assist in her home. Hall and others from Tarleton said they left with a little piece of her in their hearts and a desire to continue serving others.

“ASB has changed me. It’s made me realize that service is something I want to do for the rest of my life,” Hall said. “I’m an education major and I’ve always been interested in service but, once I got my foot in the door and started doing these activities, it made me realize I have a passion for serving others.

“Now I know that when I graduate and become a public school teacher, I want to replicate a similar ASB program because I started finding out more about myself. The saying, ‘you find yourself when you lose yourself in the service of others,’ I think proves to be true. I want to bring that mindset to my future students.”

South caRolina PuBlic Radio StoRy link:

tinyurl.com/tarletonserves

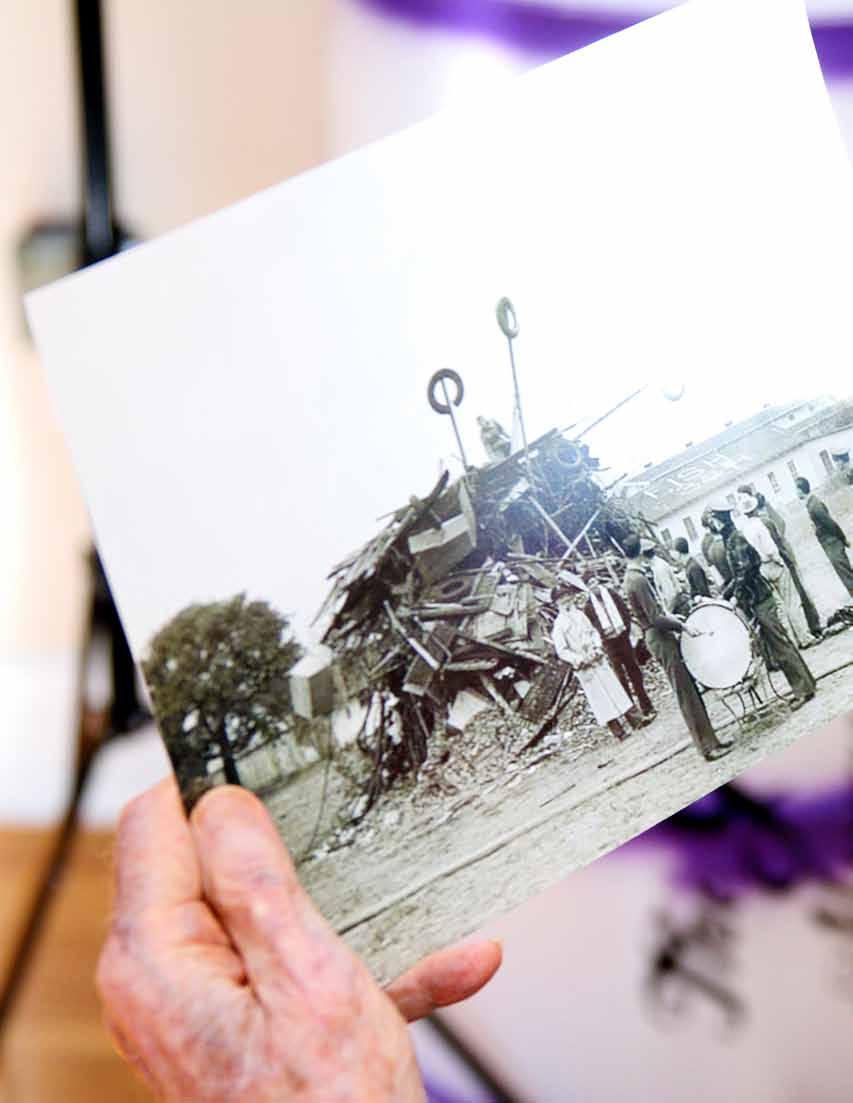

The fire that still burns...

Mickey Maguire recalls protecting the legendary 1939 Tarleton Bonfire

b y C HA n D r A An D r E w

In the 90-plus-year history of Tarleton’s bonfire, only one has reached historic proportions— the bonfire of 1939.

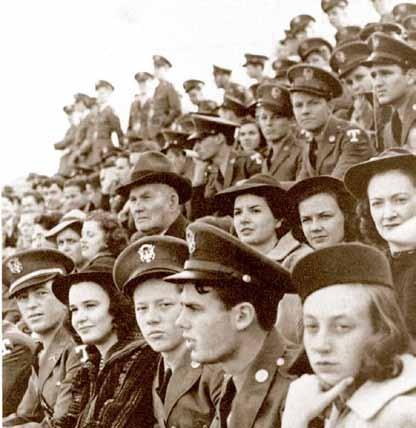

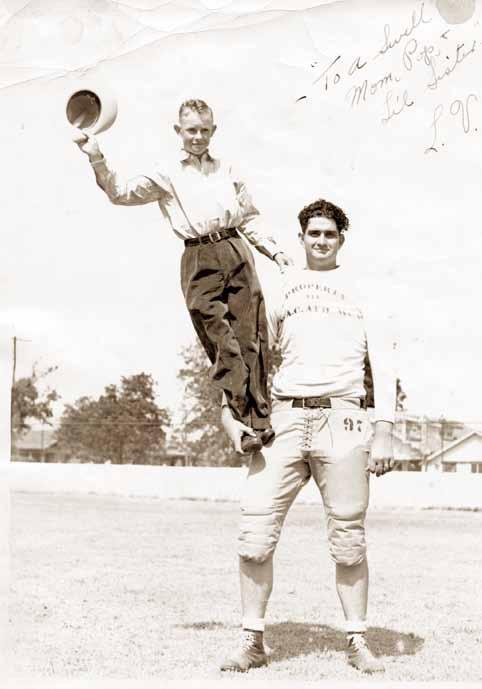

The annual bonfire tradition began in the mid-1920s to raise school spirit the evening before the annual Thanksgiving football game between John Tarleton Agricultural College (JTAC) and North Texas Agricultural College (NTAC). The bonfire at both schools preceded the intense rivalry The fire that still burns... game that dated back to 1917. “We had a terrific rivalry going on with NTAC,” said C.H. ‘Mickey’ Maguire Jr., ’40. “We were the Plowboys and they were the Grubbs. I have often told people when they ask about the bonfire and the airplane incident, ‘You need to know the rest of the story.’ And it so happens that the rest of the story came before the story.”

A photo of college-aged Mickey Maguire in The Grassburr.

Both schools developed the custom of invading the opponent’s campus in the week before the game attempting to ignite their bonfire ahead of time.

The rationale was that the raid would seize an advantage in the game by dampening their adversary’s spirit. (Tarleton’s tradition of beating the drum rose from the need for roundthe-clock guarding of the bonfire days before the game.)

In the week leading up to the 1939 game, “A group of boys who worked for the College Store, about four or five, got together and instigated a plan to go over to Arlington and burn their bonfire,” Maguire said. “It was just for meanness and because that was a thing everybody tried to do. They tried to burn ours; we tried to burn theirs.”

On Tuesday, November 28, the plan was put in motion. (NTAC’s account of the events claim that it occurred on November 27.)

“Somebody worked a deal to rent an 18-wheeler cattle truck from Beau Piedmont,” Maguire said. “He was going to charge us 25 cents apiece to carry us over to Arlington and back.”

About 50 students changed into their lab uniforms—white coveralls with the Tarleton emblem on the back. The students brought pint jars with lids. When they got to Granbury, the truck stopped at a gas station and the students filled their jars with gasoline.

“We were like a Molotov cocktail going down the road,” Maguire said. “If somebody would’ve run into us, it would’ve probably blown us all to pieces.”

Fortunately for the students, they made it safely to Arlington. The driver roared through the gates and onto campus. NTAC’s bonfire was being watched by the Grubbs, who also had a few watch fires for warmth and light.

“We were all crunched down in the trailer in our white coveralls,” Maguire continued. “I guess they thought we were a load of sheep. We drove right up to their bonfire and didn’t get a stir out of the students at Arlington.”

As the truck stopped, JTAC students scrambled out to begin their attack, throwing their glass jars on NTAC’s stack. The jars broke upon impact. Other JTAC students cut the water hose to prevent NTAC from extinguishing the fire.

“A couple of the brave ones went over and scooped up one or two of the watch fires in their arms and threw them on the stack.” Maguire said. “It just exploded; there wasn’t any way to put it out.”

The Grubbs started capturing as many Plowboys as possible.

“After the fire really got going, Beau Piedmont was wanting to get his rig out of there,” Maguire explained. “He began pulling out on the road and everybody tried to get back on the truck. We were crawling up the sideboards and the Arlington students were pulling at us and trying to get us all captured.”

NTAC captured about 10 Plowboys, then shaved their heads, rubbed them down with Absorbine Jr., and held them until the next day.

On Wednesday, both schools were in preparation mode—NTAC planning retaliation and JTAC strategizing a defense.

Unfortunately for NTAC, its dean, E.E. Davis, warned Tarleton’s dean, J. Thomas Davis (no relation), of the impending attack. Neither dean knew the specifics of the retaliation plan, but Tarleton’s dean cancelled classes for the day so his students could protect their bonfire.

NTAC’s two-pronged attack was organized by student Nicky Naumovich, a ROTC lieutenant colonel and regimental commander. More than 80 NTAC students loaded into a cattle truck and headed to Stephenville—each armed with a bottle of gasoline and a cigarette lighter.

NTAC students Chester Philips and Hatton Sumner (both enrolled in NTAC’s Civilian Pilot Training Program) rented two airplanes from Meacham Field in Fort Worth, not disclosing their intentions or flight destination. Philips and Sumner planned to fly to Stephenville, circle the bonfire and drop phosphorous “bombs” in hopes of igniting the stack. Philips would lead, with co-pilot James E. Smith, and Sumner would follow for a second attack if the first plane was unsuccessful.

But JTAC wad prepared for NTAC’s invasion.

“The ladies had formed a ring holding hands all the way around the wood stack,” Maguire said. “I seem to remember that it was a double row of women around the stack, and they were going to capture anybody who tried to break through.”

Other students—men and women—waited outside the ring for the Grubbs to arrive.

While others positioned themselves below, Maguire climbed up the stack with a water hose that he kept kinked, ready to extinguish any attempts to light the stack.

The first plane came in low and close to the bonfire.

“When I was standing on that bonfire, I was eyeballing that man on the right side of the plane,” Maguire said. “The first time he came through, we didn’t know what to expect other than he was going to firebomb. Sure enough, he started throwing things out and hit the stack, but they never did catch on fire.”

When the plane circled for another attack, some of the Plowboys climbed the water tower. They grabbed whatever items they could find to throw at the plane. On its second flyover, L.V. Risinger threw a 2-by-4-inch piece of wood, about a foot long, at the plane.

“The 2-by-4 hit the propeller, the plane sputtered and spit,” Maguire continued. “The pilot pulled up enough to clear the president’s house, then went back over the drill field.” (The plane rolled to a stop where the old rock wall sits in front of today’s Welcome Center.)

The second plane arrived in time to see Phillips’ plane going down. Sumner turned his plane around and retreated to Meacham Field, never disclosing his mission.

During the air attack, the Grubbs arrived in cattle trucks to begin their ground attack.

“The students who were on the trucks came over and tried to get to the bonfire,” Maguire said. “The women and men that were around it captured a bunch of them. They tried to set the stack on fire, but they gave up and left back to their trucks.”

The captured Grubbs received the same treatment as the captured Plowboys—block-T shaved haircuts and Absorbine, Jr. They also were treated to coffee and doughnuts before being sent back to Arlington.

Although the actions risked the game’s cancellation, officials from both schools decided to continue the rivalry. JTAC won 6-0 in Arlington.

The bonfire attacks led to a ban on future bonfires before games. At NTAC, Smith was expelled for the remainder of the semester, and Philips’ pilot license was suspended for six months. Both pilots in the attack died in World War II. Philips’ B-24 was shot down over Kiel, Germany, while Sumner died during training exercises in San Diego.

The annual game was suspended during World War II, resuming in 1945 with a safer tradition. The victor received a “Silver Bugle” and kept it until the next year’s game.

The rivalry and Silver Bugle tradition continued until 1958, when NTAC (now the University of Texas at Arlington) won the last game and the bugle. They then misplaced it. The bugle has never been found. That misfortune gave rise to another Tarleton homecoming tradition, the “Silver Bugle Hunt.”

In 1994, the homecoming bonfire was christened the “L.V. Risinger Memorial Bonfire” in honor of his role in upholding Tarleton pride. Risinger died in 1994.

Maguire fought under Gen. George Patton in World War II, returning afterward to Stephenville and his wife, Stella Pearl Nix. The two had met at Tarleton, where she was president of the Tejas Club.

Maguire, who turned 94 on Feb. 26, 2016, remains as feisty as that day in 1939 when he held the water hose to protect the Tarleton bonfire.

To hear Mickey Maguire tell the infamous bonfire story, visit www.tarleton.edu/maguire