9 minute read

A Career Shaped by Love and Love of Country

From a girl to his “beloved” Ann Arbor to a religious homage to a democratic Nicaragua, José Terán, B.S. ’56, M.Arch ’58, has followed his passions

BEFORE BECOMING NICARAGUA’S most famous architect; before building a multimillion-dollar empire, losing it all in his country’s civil war, and starting over in the United States; before a call from the White House, José Terán stepped off the train in Ann Arbor with no idea where he would lay his head that night.

Like other moments when Terán faced uncertainty in his life, he found a path forward. After walking up the hill, past downtown, and to campus, he found a place to stay — and an experience that would change his life.

“I was immediately overwhelmed, in the most positive way, by Ann Arbor,” says Terán, B.S. ’56, M.Arch ’58, whose diverse interests were satiated by the campus’s endless cultural and intellectual pursuits. “I was always discovering.”

As a boy in Nicaragua, Terán excelled in an array of subjects. As he poured over volumes in his school’s library, he discovered, through the ancient Greeks and Romans, his career path. “I was drawn to architecture because it is oriented toward solving social problems,” he says.

Because Nicaragua had no architecture schools, Terán came to the United States. In Washington, D.C., where his brothers lived, he took prerequisite courses before arriving in Ann Arbor to enroll in the architecture program.

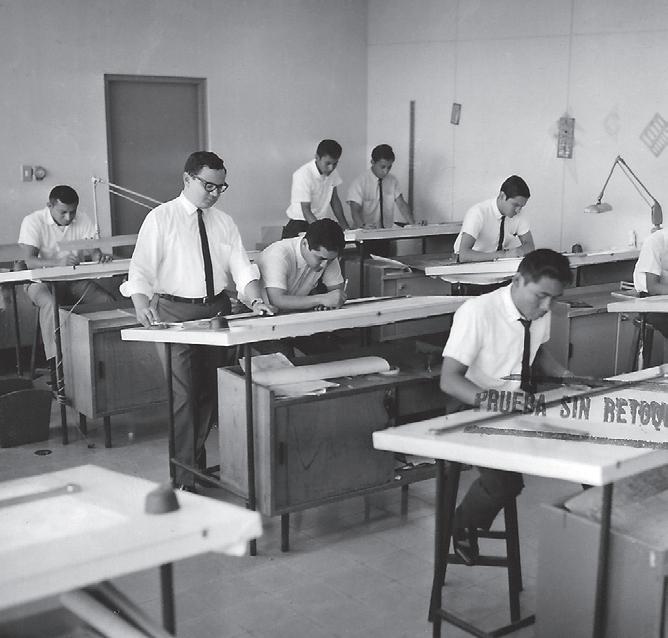

Beyond the plethora of activities that enthralled him, Terán found a way to embrace his lifelong interest in publishing at U-M. With a group of classmates, he launched an annual publication of architecture students’ work. Now known as Dimensions, the group originally gave it a singular title: “We were dogmatic,” he says. “We believed there is only one dimension.”

Terán’s academic experience was shaped by some of the architecture program’s legends. He calls Professor William Muschenheim a second father. Professor Walter B. Sanders hired him for summer work on the Unistrut framing system that he was developing. Gunnar Birkerts, the chief designer for Minoru Yamasaki, helped Terán join Yamasaki’s firm after Terán earned his master’s degree.

While working for Yamasaki (who later designed the twin towers of the World Trade Center), Terán set off on another trip that changed the trajectory of his life. Stepping back from the grueling work for the up-and-coming Yamasaki, Terán drove from his suburban Detroit home to Managua, Nicaragua — a nearly 3,500-mile trip — to take a break. At a New Year’s Eve party, in a scene straight out of a movie, he spotted a pretty girl across the crowded room. The rest was history.

“I told Yamasaki, ‘I’m sorry, but I believe that I’m not coming back,’” Terán says. “And he said that if it was for love, then he supposed it was all right.”

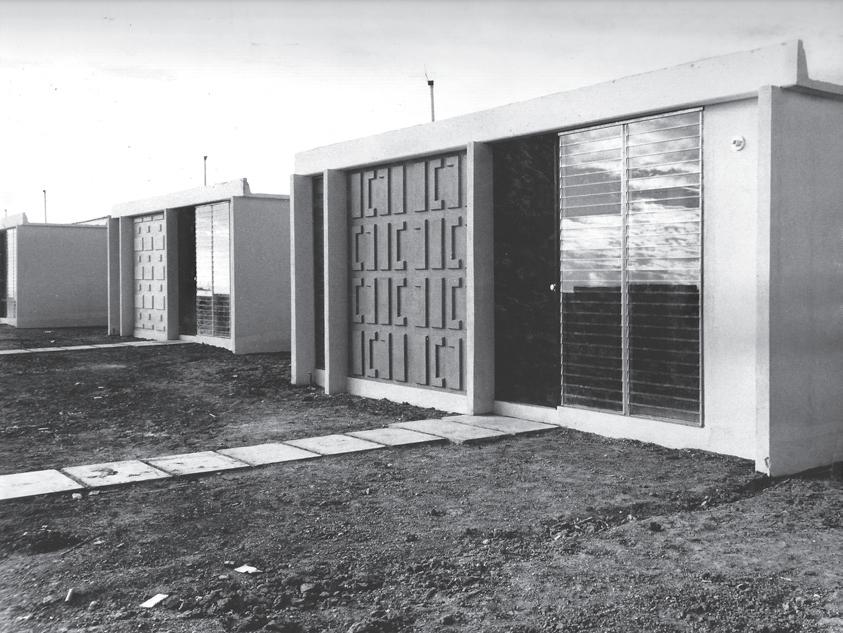

(Clockwise from top left) Rubén Darío National Theater. JFT Architecture Firm, Nicaragua,1964. Enaluf Building. INCAE business school campus in Managu. Bello Horizonte housing.

Nicaragua in the early 1960s was a place of economic opportunity. Terán connected with three childhood friends who also had attended American universities. Together, the foursome formed what would become Nicaragua’s largest conglomerate in the fields of architecture, engineering, and construction. Their companies also included real estate brokerages, banks, and wood and concrete manufacturers.

While the company grew, Terán’s status as an architect soared after another fateful encounter with a woman at a social gathering — this time a conversation about the arts with the future first lady of Nicaragua.

A lifelong lover of the arts, Terán designed a cultural center for Ann Arbor for his M.Arch thesis project. Now back in Nicaragua, he was upset by the lack of cultural institutions, especially since his country had produced one of the world’s greatest modernist poets, Rubén Darío. The country was preparing to celebrate the centennial of Darío’s birth, but “there was no dignified cultural space in the entire country where 250 people could gather,” says Terán. At a gathering following the death of his aunt, Terán struck up a conversation with Hope Somoza, the wife of Anastasio Somoza, the head of Nicaragua’s National Guard and a member of the family who had ruled the country for decades. In Hope Somoza, Terán found a fellow U.S.-educated arts lover; as they continued to talk, he told her about a group he had formed to discuss building a national theater. He invited her to their next meeting at a local school.

That night, “I was surprised to see a limousine pull up, and Mrs. Somoza got out and sat at the school desks with us,” Terán says. “She said she was very interested in our project and would do all she could to help us.”

That help included arranging a meeting with Nicaraguan President René Schick, who pledged his support. At a

ceremony marking the Darío anniversary, Terán stood in the crowd as Schick announced the new theater. He was shocked to hear the president then say that Terán would be its architect. “It was unbelievable. I was just part of the organizing group. I had assumed he would bring in a theater expert from overseas to lead the design.”

Terán flew to New York in search of consultants to help him and cold-called Philip Johnson from his hotel room. “I said I was a 30-year-old architect from Nicaragua who had just been appointed to build a national theater, and he replied that I had a big load on my shoulders.” As it turned out, Johnson was on his way to observe acoustical testing at the new Lincoln Center, which he had helped to design, and he invited Terán to join him. As consultants came by to say hello to Johnson, Johnson introduced them to Terán; by the end of the day, Terán had his theater team assembled.

“A great deal of my theater’s success comes from Philip and the people I met through him,” Terán says.

Vaulted to prominence by the success of the theater, Terán’s next big break came when Harvard University asked him to design its new INCAE business school campus in Managua. “They told me their only design requirement was that it be Central American architecture,” Terán says. “I thought to myself, ‘What the hell is Central American architecture?’ So I invented it.” Terán’s design stemmed in abstract ways from traditional Spanish influences and mimicked the layout of a convent, with a long arcade connecting the rooms.

While the Rubén Darío National Theater and INCAE were celebrated for their beautiful design when they were dedicated, they were revered in another way when a mas

sive earthquake leveled Managua in 1972: the INCAE building survived unscathed. In the center of the city, which was almost entirely reduced to rubble, the theater suffered very minor damage. “I became somewhat famous after that,” Terán says modestly.

Less than a decade later, Nicaragua would experience a different kind of destruction. After Anastasio Somoza, the husband of Terán’s theater champion, came to power, the Soviet-backed Sandinista revolution plunged the country into years of political turmoil. As violence escalated in 1978, Terán, his wife, and their daughters fled first to Guatemala and ultimately to the United States. He credits then U-M Architecture Dean Robert Metcalf’s letter of recommendation with helping to expedite their relocation. “When the U.S. immigration officer saw that I had done research at the University of Michigan, he told me, ‘Don’t worry. You’ve got your visa,’” Terán says.

Terán’s connections helped him reestablish his career in Houston. He went on to become founder and CEO of Natex Corp., an architectural, engineering, and facilities management firm, and spent 20 years enjoying success born from being an integral part of Houston’s rapid growth. During that time, Terán also established CFI, a holding company in Nicaragua with 20 different entities. With funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development, CFI oversaw eight residential projects in Nicaragua with more than 15,000 single-family detached homes. “I became an expert on low-cost housing in Central America and am proud of the impact I was able to make on ordinary Nicaraguans as a result,” he says.

In 2003, living in Key Biscayne, Florida, and thinking he was retired, Terán received a call from President George W. Bush’s staff. Bush, whom Terán knew from Bush’s days campaigning to be Texas’s governor, wanted Terán to serve on the board of directors of the National Institute of Building Sciences. During his six-year term, Terán helped to establish the International Alliance for Interoperability, now called the buildingSMART alliance, which streamlined the exchange of information between software applications used in the construction industry.

But for all of his success in the U.S., another cultural project in Nicaragua defines the latter part of his career.

While at Michigan, Terán befriended a fellow architecture student named Tom Monaghan. When Monaghan dropped out of school to run his Ypsilanti restaurant, DomiNick’s, Terán regularly ate there because they served up big plates of spaghetti for under a dollar. By the early 1990s, Monaghan had turned his restaurant into a global empire known as Domino’s Pizza — and the devout Catholic was financing the construction of a new cathedral to replace the one that was destroyed in Managua’s 1972 earthquake. He had commissioned Mexican architect Ricardo Legorreta to design it, but when Terán contacted Monaghan to congratulate him on the project, Monaghan asked Terán if they could meet.

During a day of discussions at Domino’s headquarters in Ann Arbor, sitting in buildings designed by Gunnar Birkerts, Monaghan said there was friction between Legorreta and Nicaragua’s cardinal and asked Terán to step in as construction manager. Terán wasn’t sure he wanted to get involved. Then Birkerts, who maintained an office in the complex, walked in, got up to speed on the discussions,

They told me their only design “ requirement was that it be Central American architecture. I thought to myself, ‘What the hell is Central American architecture?’ So I invented it.” — José Terán, B.S. ’56, M.Arch ’58

and took his protégé aside. Birkerts, a Latvian, said he had hesitated when asked to design the new national library in the capital, Riga. Ultimately, he realized it would be a way to help his country as it transitioned from decades of communist rule. With Nicaragua having just held its first democratic elections in 1990, Birkerts told Terán that he now faced a similar opportunity.

“I went downstairs and told Tom yes,” Terán says.

Terán’s involvement with the Metropolitan Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception of Mary was “a top-tobottom reorganization” to bring the design into compliance with the parameters of the Second Vatican Council. The cathedral was controversial in many ways, including the American bankrolling and the design — which some said resembled a mosque and others said resembled breasts. But it received an AIA Design Award in 1994 and ultimately was embraced by Nicaraguans. Terán calls the cathedral the most important building in Nicaragua and says that of all the projects he has been involved with, the cathedral is “absolutely, totally special.”

Like the architect whose storied career began by hauling his worldly possessions through Ann Arbor, looking for a place to stay. — Amy Spooner