7 minute read

INK ON PAPER

By Sara Hilton

Shoeboxes of handwritten letters. Journals and diaries. Postcards. These are the surviving words of everyday life, the documents that chronicle love and loss, grief and healing, passion and longing, and even the most mundane. Here are a few local letters of interest from the past...

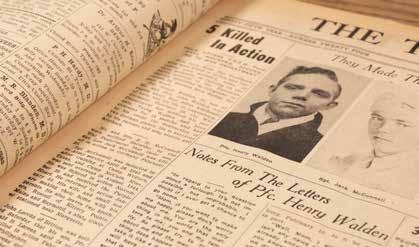

On February 26, 1945, Mr. and Mrs. John Walden of Tecumseh were notified that their son, Pfc. Henry Walden was killed in action in Luxemburg, Germany. Henry was just 20 years old when he died. In 1945, excerpts from his letters home were published in the Tecumseh Herald for the community to read. Once again, ink pressed to paper gave a young man a voice, even after he was gone. His words and his tone reveal both sides of the coin of war — pride and despair. In his letters, we see a young man who is ready to die for something in which he believes. We also see the weary homesickness of a young man telling his mom that he has seen enough. “In regard to your question about a furlough,” he writes, “it’s not impossible, but improbable. I doubt if I ever get a chance to go home.”

“Mom, if you want to make me happy, please don’t worry about me. You are the only thing in the world that matters to me; you and my family. So please try to forget about me and the war. If anything happens to me just take it like a dream. I at least will have died for something that is worthwhile. Until a person has been over here he wont know what we have in the United States. In fact, he will never know the meaning of the words liberty and freedom.

February 10, 1945 Well, Mom, I guess there isn’t any news that you don’t already know about, probably you know more about it than we do up here. I think I told you that I am in the Third Army. Ole Blood and Guts Patton. What a man. I’ve got to make this one short, I’m taking a load of fellows to a movie tonight.

February 16, 1945 Well, Mom a lot has happened since I wrote you last. We crossed into Germany in one day and the same day I shot down another plane. It was an ME109. We were sitting there along side the road and here she came, going like a bat out of hell. So I jumped in our [blocked out] and one burst and she started to fall.

I hope this thing is over with soon because I’m getting spring fever. I want to come home. I’ve had enough of this. I’ve seen all that I want to see. Our truck is in ordance getting repaired and February 20, 1945 The cake you sent me was very good and I gave it to the cook for all of the boys. When they get anything they do the same. Boy did I get a scare today. Some other fellow got his foot blown off and it still lays there. I hope I’m this lucky the rest of my life. n

“Papa is sick,” wrote Tecumseh’s Perry Hayden in his journal on Oct 11, 1918. “Think it might possibly be from influenza. That is the epidemic in our country at present. Thousands of cases in the concentration camps. Gov. Sleeper issued a proclamation asking all public meetings to be stopped.”

From 1914 to 1952, Tecumseh resident Perry Hayden recorded his daily life in journals. In 2005 his daughter, Martha Woodward, donated the journals to the Tecumseh District Library, where they serve, in one sense, as an eyewitness account to history. But there is something more when you see his penciled handwriting sprawled across each page. There are days of normalcy. “Worked at the bank.” And there are moments of emphatic anger, the irate pressure of the pencil on the page. “THE SONS of Bitches” he writes and then furiously underlines eight times when Germans fire on passenger ships. However, throughout the fall and winter of 1918, there is a problem. His papa is sick. so that I was pretty nearly all in when the bed down.

October 12, 1918 Papa is a little better but still enough under the weather to stay in bed nearly all day. Great epidemic of Spanish Influence prevalent.

October 14, 1918 School was closed today because of the Spanish influenza. Five teachers and dozens of pupils being taken with it.

October 20, 1918 No church. Closed by state order to prevent epidemic of Spanish flu from spreading. December 20, 1918

December 11, 1918 Papa in bed all day.

December 12, 1918 I left the bank at 11 o'clock to take papa to Ann Arbor in the car to see a specialist…. Papa is very very weak. I asked the Dr. if there was any hope. that there still was a little hope. While in the hospital I was taken with cold chills. (remarkable, eh? You’d think chills would be warm?) Had a hard drive home, no lights and rotten roads we arrived home. Mother gave me some ginger tea and a whiskey sling and bundled me off to bed. Papa is too weak to get upstairs so they brought

December 13, 1918 I have the 'Flu' stayed in bed all day.

He said papa was a very sick man but I get better every day and papa gets weaker.

Ink on Paper continued...

December 21, 1918 This morning about 7:30 Dr. Conklin came up to my room and while administering to me said that papa was very very low and that he probably wouldn’t live much longer. I was prepared for these words, but when mother came up a few minutes later with tears streaming down her cheeks and told me that I was the man of the house now, I gave up and just bawled like a baby. Papa had passed away at about 7 o'clock.

December 25, 1918 The flu epidemic is right now at it’s worst stage. n

“In my sleep, your form appears in my imagination. In my dreams I see you, and I hear your voice. I feel the soft touch of thy lips as they meet, in my dreams, mine. I awake to the reality that I am far distant from Maria and what is more heart wrenching that she loves not me.”

1837 Letter to Maria from Consider Alphonzo Stacy

“She loves not me.” Separated by many miles, young Consider Alphonzo Stacy must convince Maria that despite his lack of wealth, there would be “no more sincere lover” for her than him. Yet the distance between them is a vast and unsettled land, and all he can do to convince Maria to love him back is to take ink and press his longings onto paper.

Consider Alphonzo Stacy left New York for Tecumseh in 1836 to study law under a mentor. He went on to become a judge, a newspaper editor, an abolitionist, and one of the most wellknown and iconic figures of Tecumseh history. He is remembered for his accomplishments and as the aging man in black and white photos. We have dates of birth, marriage, death — the lifeless hashtag-like markers of the dead. Yet, the same ink pressed to paper that voided the distance between himself and Maria, also voids the distance of time and death. In one letter, this stoic icon of history becomes alive to us by his own words, ink pressed to paper resurrects a whole man, a man longing for the woman he loves. “I can say with truth Maria, oh that I could see you that I could talk with you. You say I may stay in Michigan for years. Maria I had calculated to come back next summer. I could not bare to think of longer separation from Maria. But I then had hoped. Now I have nothing to call me back. I shall not probably return for years, perhaps never.”

It is from what he calls “a land full of strangers,” that he finally bids farewell. “Adieus dearest to me though I to thy arms naught.” The letter is folded and sealed with wax, and he sends his ink pressed to paper across the void. He sends his heartbroken and passionate love to a woman who loves him not, to the very woman he would marry in 1838. n

Unlike history books, ink pressed to paper chronicles the firsthand, the whole, the flesh and blood stories of those who went before us, and remind us that from century to century, generation to generation, we are the same.

The world needs Scone Day...