9 minute read

Preparing for war: 1918–19 — Jim Rees

ARKLOW – Jim Rees

Preparing for war: 1918–19

Advertisement

In April, May or June, 1918, John Broy, who was the quartermaster of the Kynoch’s munitions factory in Arklow, told his captain, Matt Kavanagh, that he had a brother Éamon (Ned) in the Dublin Metropolitan Police, who was posted in Dublin Castle and was willing to give information if he could be put in touch with ‘the right person’. As Kavanagh had no contact with GHQ at that time, he handed the message to Micheál Staines who, in turn, transmitted it to headquarters.

In April 1918, conscription was extended to Ireland. This caused a backlash of anti-British sentiment throughout the country. Within days, 200,000 people had signed a pledge against it. Anti-conscription meetings were held throughout County Wicklow and, as a result, membership of the Irish Volunteers swelled.1 Arklow was no exception to the general disquiet, although anyone working in Kynoch’s was exempt from conscription as each employee had been issued with a card declaring their work to be of value to the war effort.2

Conscription gave the republican movement the boost it so badly needed. An incident in Arklow recalled by Matt Kavanagh indicated the mood of the people:

Matt Kavanagh (1895–1973), Arklow Company Captain, later Commandant of the IRA East Wicklow Brigade . Photo: Courtesy of Jim Rees

Sometime in either June or July 1918, two special constables, who were guarding Kynoch’s munitions works, were arrested, through mistake, by the RIC for carrying firearms. These men were from Wexford and local people, equally mistaken, believed that they were IRA volunteers A hostile crowd formed to attempt to rescue them, stoning the police A baton charge was ordered, as a result of which eight members of the local company were arrested

3

These eight men were tried before a special criminal court, one of the first such courts set up in the country. Kavanagh, working with M. J. Dwyer, a solicitor practising in Arklow and later County Wicklow Registrar, briefed Cecil Lavery, who defended the eight men without remuneration (Lavery later became a judge of the Supreme Court from 1950 to 1966), that GHQ had issued instructions that the men were to recognise the court. Two men were sentenced to two months in jail, and the other six were acquitted. One of those convicted was not a member of the IRA.

Gathering arms

Matt Kavanagh wasn’t happy with the fact that his Arklow company had no access to small firearms, a situation he discussed with Seán McGrath. McGrath, who was secretary of the Self-Determination League in Great Britain, was married to Annie Redmond from Arklow. Because of that family connection, McGrath spent his annual leave in the town. He told Kavanagh that he could supply revolvers if arrangements could be made to have them collected in Liverpool. Kavanagh placed an order for £50 worth, which would pay for ten revolvers and 500 rounds of ammunition. The drop was to be made at an address near Edgehill railway station in Liverpool. Kavanagh decided to collect the weapons himself. When he got there, however, he was informed that they had already been collected for GHQ in Dublin.

This was a great disappointment to Kavanagh, but worse was to follow. Very soon after Kavanagh’s arrival home, Tom Cullen, often described as Michael Collins’s bodyguard, and who would later hold the rank of Major General in the Free State army, arrived in Arklow and ordered Kavanagh to accompany him to Dublin immediately. Their destination was Cullenswood House on Oakley Road in Ranelagh, where Kavanagh met Collins for the first time. Collins started off with a terrible harangue and abused me at a frightful rate for daring to interfere by tapping a Headquarters source of supply for arms Micheál Staines, who was present during this interview, said something on my behalf, whereupon Collins appears to have changed his views towards me He shook hands with me and congratulated me for trying to secure arms He said that there were some people trying to avoid getting them He agreed to give me six revolvers for cash and three hundred rounds of ammunition They were not the type of revolver I was actually

Cullenswood House, Ranelagh, Dublin, where Matt Kavanagh met Michael Collins. Aftermath of destruction by Auxiliaries, March 1921. Photo: Courtesy of the National Museum of Ireland.

looking for, but a 38 revolver made by Harrington and Richardson of America I got these just before the general elections in 1918 4

Collins’s remark about ‘people trying to avoid getting guns’ might have referred to an incident in Bray in which nine out of ten rifles sent to there were returned to HQ.5 Despite winning Collins’s approval, Kavanagh and most, if not all, Wicklow Volunteer officers were outside the inner circle of the republican leadership in 1918. Kavanagh admitted that he didn’t even know where GHQ was, as he was not ‘sufficiently well known in the movement to be told.’

This was a situation he wanted to change. He went to the Sinn Féin offices at 6 Harcourt Street in Dublin to try to make contact with someone in GHQ. It was suggested that he write to Seán McGrath, which he duly did, using the Harcourt Street address to add legitimacy to the letter. By a quirk of fate, McGrath was arrested in England on the platform of Rugby railway station

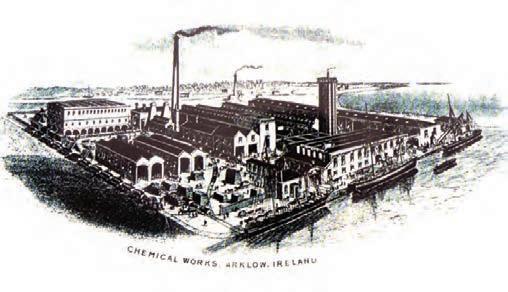

Kynoch Works, Arklow.

a few days later and among the items in his possession was Kavanagh’s signed letter. McGrath’s subsequent trial was something of a cause célèbre. Implicated with him was a man called Burrowes, manager of the Midland Gun Company, who was also arrested. Both were charged with exporting arms to Ireland. They pleaded that the arms were for the Ulster Volunteers. Burrowes received a sentence of six months’ imprisonment, and McGrath got twelve months. Kavanagh seems to have escaped implication through the letter, but from then on he had close contact with GHQ, being named as one of the principal organisers in the south Wicklow and north Wexford region.6

The war in Europe ended on 11 November 1918 and the first general election to be held since 1910 got under way in December. As elsewhere, County Wicklow Volunteers acted as personation agents at polling booths, helping to ensure the enthusiastic return of the two Sinn Féin candidates, Seán Etchingham and Robert Barton. Barton was arrested two months later.

Kynoch’s closure announced

In early 1919, Kynoch’s re-announced its intention to close the Arklow factory. Earlier indications of closure had been made with notices issued to employees in March 1918, but negotiations had won something of a temporary reprieve. With the need for munitions now back to peace-time levels, the company was no longer viable. It had lost its commercial explosives markets and there was no option but to close the factory. Or so it was claimed. There was an outcry from those who felt the town deserved better because it had contributed greatly to the war effort. The reality was that there was another underlying reason behind the

closure: the rise of militant nationalism, especially in the wake of the landslide election of Sinn Féin in December and the sitting of the First Dáil in January. Local pressure, however, did wrest one concession: the closure would be phased over two years.7

Just as the introduction of conscription to Ireland in April 1918 had acted as a recruitment campaign for the newly formed IRA, the end of World War One saw many of those new recruits fall away. A further major blow to republicans in the south Wicklow area was the arrest in March 1919 of Jim O’Keeffe, OC of the 5th Battalion. O’Keeffe never returned to his post, and the Brigade OC, Séamus O’Brien, carried out O’Keeffe’s duties as well as his own, until Jack Holt was appointed Acting OC.8

Boycott of RIC

In early 1919, the Dáil introduced a strategy that had worked well in the 1880s — a boycott of RIC personnel and anyone who had dealings with them. This, it was hoped, would put sufficient pressure on RIC members and their families to affect morale and even reduce numbers. Nationwide, resignations from the force increased and recruitment fell. In Wicklow, things were so quiet that it was deemed safe enough to close rural barracks so that personnel could be transferred to more potentially dangerous locations around the country.9

Raids for arms

The Arklow company continued to carry out raids for arms on private houses, netting about thirty shotguns and some old revolvers. One of the best weapons to come into their possession was a British army issue .45 Webley revolver which was lifted from the coat of an army officer at Woodenbridge Golf Club10 and used to keep the sentries quiet in an arms raid on Kynoch’s soon afterward. Three Lee Enfield rifles and 150 rounds of ammunition were taken. Matt Kavanagh and his men must have been pleased with this success, but once again GHQ burst his bubble. The raid was reported in the local paper and came to the notice of GHQ, which demanded that the rifles and ammunition be handed over, presumably for redistribution to a more active company.

The rest of 1919 was quiet in Arklow; the following year, however, saw an increased level of action by the local company.

Notes

1 Christopher M. Byrne, who in 1914 had taken it upon himself to organise the first County

Wicklow Irish Volunteer companies, remained active in the intervening years. He was organising Volunteers again in 1917, and as a Rathdrum Poor Law Guardian, he made his strong Sinn Féin leanings known wherever and whenever possible. At a meeting of the Rathdrum Board of Guardians in October 1918, he gave notice that at their next meeting he would propose that ‘the pictures of the English monarchs hanging in Ashford dispensary be immediately removed.’ While not exactly a declaration of war, it is indicative of the feelings running in the county. (Wicklow County Council Archives, Rathdrum Board of Guardian Minutes, 20 Oct 1918, quoted in Brian Donnelly, For the betterment of the people (Wicklow, 1999), 35–36). 2 One such card was exhibited in Arklow Maritime Museum until recent years. 3 Matthew Kavanagh, BMH.WS1472, 4. 4 Matthew Kavanagh, BMH, WS 1472, 3. 5 Henry Cairns and Owen Gallagher, Aspects of the War of Independence and Civil War in

Wicklow 1913-1923 (Bray, 2009), 3. 3. Why these rifles were returned is unclear. A public collection in Bray had raised £38, which was given to HQ. In return, ten rifles were sent out. A committee meeting was called to discuss how to distribute the weapons, but it was decided that they should be returned to HQ and a refund requested. 6 Frank Henderson, BMH.WS821, 84 and 94. 7 Jim Rees, Split personalities, Arklow 1885-1892 (Arklow, 2012). 8 Cairns & Gallagher, 14. Also, Matthew Kavanagh, BMH.WS1472, 5. 9 Cairns & Gallagher, 17. 10 Matthew Kavanagh, BMH.WS1472, 11.