16 minute read

Doggett at Large

by JOE DOGGETT :: TF&G Contributing Editor

Snakes on a Trail

SO GOES THORTON BURGESS’S classic children’s tale.

Regrettably, if the Bunny Trail happens to be winding through the deep South Texas brush, Peter’s next hippety-hop might land him squarely in front of a huge western diamondback ra lesnake. e six-foot pit viper strikes in a blur and Peter squeals in pain and terror. Poor Peter did not just receive a long-overdue COVID vaccine; he got twin hypodermic doses of hemotoxic venom from statistically the most dangerous snake in North America.

He dashes several yards and falls. e burly ra ler uncoils and, using its heat-sensing facial pits, con dently follows the warm-blooded trail to claim a satisfying meal.

Texas truly is snake country. e vast size of our state combined with mild temperatures and diverse ecological regions allows an abundance of snakes to ourish. At least 72 species have been documented (Texas Snakes, Werler and Dixon, 2000).

Ten of these species are ra lesnakes. e most plentiful and widespread (roughly the western two-thirds of the state) of the buzzing options is Peter’s nemesis, Crotalus atrox. e western diamondback is the largest, with documented specimens topping seven feet. Such a diamondback might weigh 12 to 15 pounds. In the real world, that is plenty of snake. Most adults are less than four or ve feet—and that’s still plenty of snake. e eastern diamondback of the southeastern lowlands can exceed eight feet, but the distribution numbers are not there; they are seldom encountered. e awesome eastern issue is not as irritable. is does not suggest that the western diamondback instigates a acks on humans. Instead, it tends to come out swinging—striking—when its space is violated, or it feels trapped.

Texas records approximately 1,000 to 1,500 venomous snake bites each year, and the highstrung diamondbacks account for roughly one-half of the tally. Southern copperheads, common in urban areas of southeast Texas, muster about onequarter, with co onmouths a distant third. at’s the bad news. e upside is that only one or two people die per year.

Fatalities are minimal because quali ed medical help in Texas is rarely more than an hour or two away—and many rural facilities are experienced in dealing with snake bites. Contrary to western lore, the venom is relatively slow-acting on a human-sized target. But, by all reports, a “hot” bite (compared to a dry pop) is an excruciating and long-lasting ordeal.

Incidentally, experts agree that several semirare ra lesnake species (mainly in West Texas) have venom that drop-for-drop is more toxic. But the diamondback boasts three trumps: great size, large glands, and long fangs.

A four- or ve-footer coiled in the typical aggressive posture with head and neck elevated in an intimidating “S loop” can use the wide, at coils to launch a formidable strike. With solid purchase, the superfast lunge may carry up to one-half the body length.

Ironically, the bite from an immature diamondback is no bargain. Experts also conclude that in most cases the toxicity from a juvenile is stronger than that from a full-blown swashbuckler. e positive news is that the young snake has much less carrying capacity.

South Texas is the mother lode for diamondbacks, as any experienced brush country rancher or hunter will a est. Other high-density regions are western portions of the Hill Country and the barrier islands and coastal prairies along the lower and middle coast.

As a boy growing up in Houston during the late ’50s, I was a junior-high herpetologist, scouring the banks of urban bayous and elds for an impressive assortment of snakes. But not once did I see or even hear of a diamondback in northern Harris County.

We eschewed parental warnings and captured the occasional southern copperhead, as well as several co onmouths and Texas coral snakes, but the only ra lers I recall were two western pigmy ra lesnakes near Bu alo Bayou/Memorial Park.

I do not now condone catching dangerous snakes. ose rash forays occurred 60 years ago, and three of my “collecting” friends were bi en— one on the thumb, one on the index nger, one on the arm.

It is a minor miracle I was not nailed. Leave the poisonous ones to the experts and understand that sooner or later many ra lesnake handlers get well and truly zapped.

One of the oddities of the outdoors is that an individual u erly terri ed of serpents cannot walk 100 yards through brushy terrain during mild weather without stirring up a wad of writhing coils. Meanwhile, those of us stoked to see the occasional ickering forked tongue can poke around for days without ushing so much as a piddly ribbon snake.

Frankly, following that theme, I have not encountered all that many —one here, one there, that sort of thing. I have yet to see an honest sixfoot diamondback in the eld.

Such a beast viewed at safe distance would be an awesome spectacle for anyone who appreciates the wildness of Texas. e fact that one could swallow Peter Co ontail says something about the bulk and mass of the reptile.

But, to repeat, the average western diamondback is less than four feet in length. Camp re smoke aside, those are the documented facts. I once had to hand-grab a furious, escaped diamondback that was at least four feet—but the less said about that herpetological misadventure, the be er.

If, on an innocent outdoor foray, a terrible mistake carries you within reach of a whirring buzz and a ashing strike, current wisdom recommends forge ing all the celebrated do-it-yourself treatments involving knives, razor blades, suction cups, tight tourniquets, ice packs or whisky bo les.

As they say, the best rst aid for a venomous snake bite is a set of car keys. Or, increasingly, perhaps one of those snazzy vehicle starter bu ons. Either way, crank that sucker and aim amid a cloud of dust and caliche for the nearest medical facility.

Email Joe Doggett at ContactUs@fishgame.com

INTER WEATHER THAT hit during the week of February 14, 2021 led to sh kill events on the entire Texas coast. If sh do not make it to a refuge in deeper, more temperature stable water during cold weather, they may die when water temperatures reach a certain threshold.

A er the rst sh kill was reported in the Lower Laguna Madre, Texas Parks and Wildlife (TPWD) biologists began the process of assessing kills across multiple bay systems on the coast.

Impacts from the February 2021 Freeze

An estimated minimum of 3.8 million sh were killed on the Texas coast during the February 2021 freeze. is sh kill consisted of at least 61 species. Non-recreational species contributed to 91 percent of the total mortality in numbers of sh. is includes species such as silver perch, hardhead cat sh, pin sh, bay anchovy and striped mullet.

Although they’re not sought a er by most anglers, nongame sh are ecologically important, providing food for larger game sh as well as adding to the overall diversity of Texas bays. Recreationally important game species accounted for the other nine percent of the total. Of that nine percent, the dominant species included spo ed seatrout (48 percent), black drum (31 percent), sheepshead (eight percent), sand seatrout (seven percent), red drum (three percent), gray snapper (two percent), and red snapper (less than one percent).

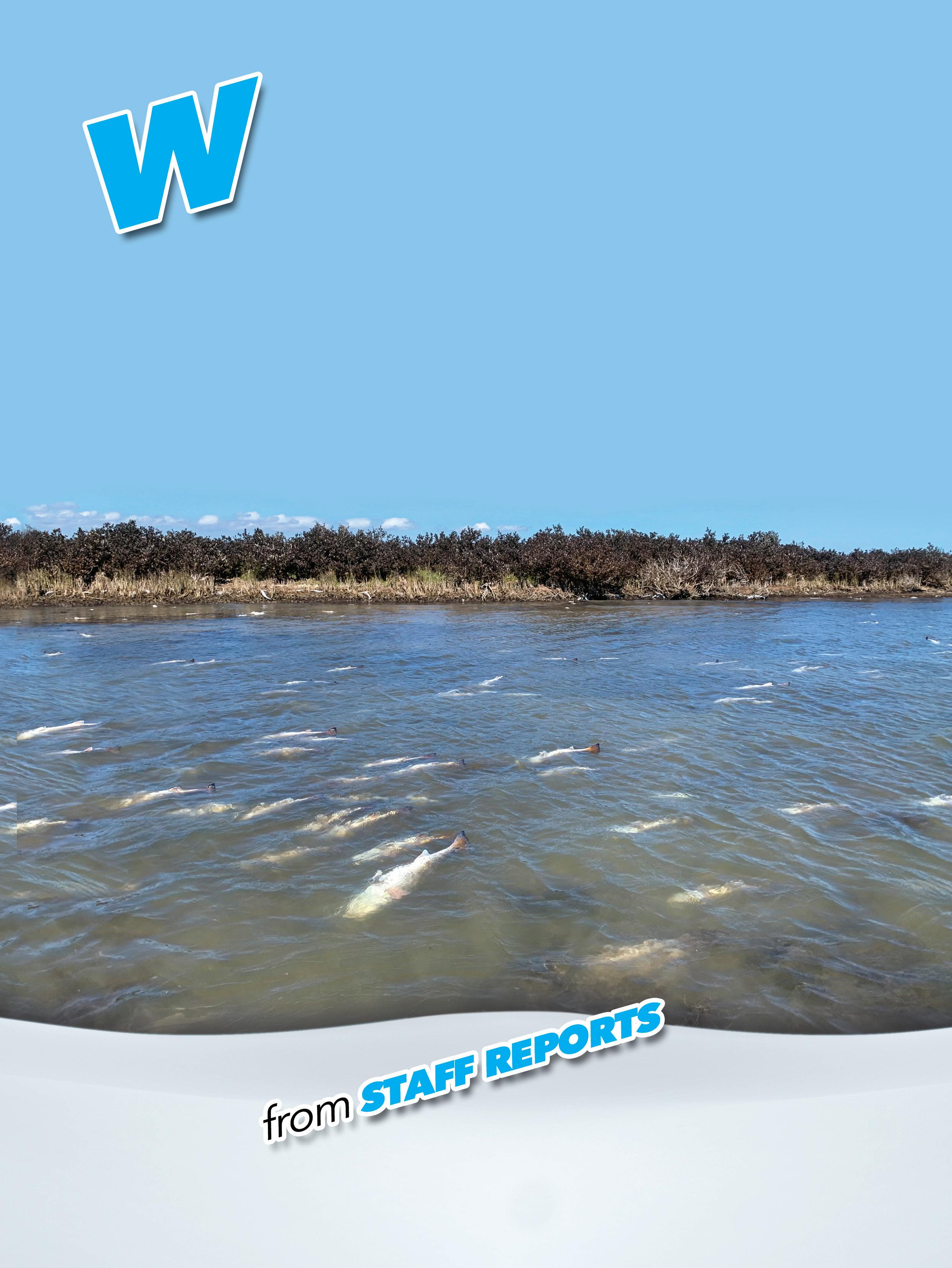

Both the Upper and Lower Laguna Madre bay systems were hit particularly hard. e Lower Laguna Madre had the highest mortality of Dead redfi sh fi ll an area in spo ed seatrout with an estimated 104,000 Pringle Lake at sh killed. at comprised 65 percent of the Espiritu Santo

Bay.

total estimated spo ed seatrout killed. When combined with the Upper Laguna Madre, it comprised 89 percent of the total estimated spo ed seatrout mortality along the Texas coast. Similarly, the Upper Laguna Madre had experienced black drum mortality at an estimated 82,600 sh and comprised 78 percent of the coastwide black drum killed.

Historical Comparison

is is not the rst freeze to occur in Texas coastal waters. Multiple freezes during the 1980s killed almost 32 million sh, with the most severe impacts being on the lower coast.

Although the February 2021 event impacted a large area of the Texas coast, the overall number of sh killed in this event appears to be lower than any of the three freezes in the 1980s.

“Using history as a guide, we believe our shery has the potential to bounce back fairly quickly as it did a er the 1980s freeze. Based on our long-term monitoring, we saw

This was one of the few dead trout found in Sabine Lake. Areas of the Middle Coast, Lower & Upper Laguna Madre were hit hard.

the recovery in terms of numbers of spotted seatrout bounce back in approximately two to three years. This does not mean the fish size and age structure were the same as prefreeze, but the overall numbers did return in that timeframe.” said Robin Riechers, Coastal Fisheries Division Director.

However, the spotted seatrout mortality in the combined Upper and Lower Laguna Madres is comparable to the events from the 1980s. Below is a breakdown of each event in the 1980s. • December 1983: 14.4 million fish killed with a geographic extent of the entire coast. • February 1989: 11.3 million fish killed with a geographic extent of East Matagorda Bay south to the Lower Laguna Madre. • December 1989: 6.2 million fish killed with a geographic extent of the entire coast.

The February 2021 freeze appears to have been larger than any other fish kill seen since the 1980s, including those in the 1990s and 2000s. The 1997 freeze saw 328,000 fish killed but had a significantly higher percentage of game species killed (56 percent) than in 2021.

Although some areas of the coast and some species of fish were clearly impacted more than others, overall this is the worst freeze-related coastal fish kill Texas has experienced since the 1980s.

“There are some important lessons from those historical events that we need to draw upon as we work to accelerate the recovery of our fish stocks, particularly speckled trout along the mid and lower coast,” said Carter Smith, Executive Director of TPWD. “The most obvious, and immediate one for speckled trout is conservation, a practice where every Texas coastal angler can make a contribution right now. Practicing catch and release and/or keeping fewer fish to take home in areas like the Laguna Madre will only give us that many more fish to rebuild from as we augment populations through our hatchery efforts, and we carefully evaluate what regulation changes may be needed to foster a quicker recovery for our bays.”

Fish Kill Assessment Methodology

Assessments for large geographic fish kills occur using a phased approach. The first phase is determining the geographic extent and distribution of fish. This is achieved through observations from staff, state, and local partners as well as the public. Rapid assessments to determine the rough estimates of the number of fish killed as well as species impacted are completed.

Next, TPWD coastal teams are assigned sampling areas, and staff count, measure and record each individual fish present in an area. By following American Fisheries Society guidelines for sampling in this manner, a summary can then be completed for each bay system along with a coast wide assessment. While assessment methods have evolved slightly over time due to better technology and resources, general methodology for how TPWD assesses fish kills is comparable over the decades.

As the TPWD Coastal Fisheries Division continues to assess this event and determine the impact to the overall fish populations, they will compare it to past freezes and brief the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission (TPWC) on those impacts relative to the

historical record of coastal freezes. In the near term, TPWD coastal sheries biologists will continue to analyze the impacts on populations by species and bay systems. ey will work with the TPWC to determine what actions, if any, may be needed to accelerate recovery of sh populations and to help address future events. e Coastal Fisheries Division’s longterm routine monitoring programs (e.g. gill nets, bay trawls, and bag seines) allow for analysis of this freeze by comparing it to past events, even before additional routine sampling is conducted. Additionally, as a part of year-round survey e orts, biologists are already collecting information from recreational anglers. is provides additional information regarding the impacts of this cold-weather event on angler catch rates of game sh. TPWD will also be evaluating an increase in spo ed seatrout production at its coastal sh hatcheries to aid the recovery e orts

What can you do to help? As sh stocks recover from this freeze, anglers are encouraged to practice conservation by choosing to catch and release sh or to take only those sh they feel they need to take home to eat. Conserving sh now can only aid in a quicker recovery.

Dean Thomas of Slow-Ride Guide Services with a dead tarpon he found after the freeze in the Aransas Pass area.

STRIPED BASS WON’T win any statewide popularity contests in these parts, but there are a handful of Texas lakes where Morone saxatilis kicks butt, takes names and grabs plenty of attention along the way. Anyone who has ever caught one of the saltwater transplants cracking the double digits will surely agree with the allure. The striper is one rough customer, widely known for its brute strength and territorial disposition. This tenacious fish might be described as a piscatorial cross between Dick Butkus and Mike Tyson wrapped into a silvery stick of dynamite tipped with a really short fuse.

That fuse tends to become particularly short during late spring. That’s when warming temperatures spur their metabolism and spark violent feeding frenzies on hapless schools of shad. In some cases, it’s not uncommon to see virtual blood baths unfold in the shallows as marauding schools of stripers drive the succulent bait fish to the surface and gobble them up at will.

Stripers rarely hold anything back when they pin a group of shad against the surface. Sometimes the attacks are so vicious that it sends the succulent bait fish cartwheeling in a last second dash for safety. Venture onto any reputable striper lake over the next 30 to 45 days and there’s a good chance of cashing in with a topwater plug or any number shad imitations.

So, which Texas impoundments offer best opportunities for getting in on late spring’s striper fishing bonanza?

To learn more, we reached out to regional and district fisheries biologists with the Texas Parks and Wildllife Department.

Here are our Top Five striper lakes for 2021:

NO. 1: TEXOMA

SIZE: 75,000 ACRES

LAKE RECORD: 35.12 LBS.

COMMENTS: This is a five-star impoundment that supports one of the few self-sustaining striper fisheries in the U.S. Oklahoma biologists jumpstarted the population with generous stockings from 1965 through ’74. Since then, the fishery has carried itself on bountiful spawning runs that occur each spring in the free-flowing Washita and Red Rivers that feed into Texoma.

The striper factory cranks out mega numbers of eating-size fish, but it’s also one where trophy hunters have good shot of connecting with fish in the 14- to 17-pound range, or quite possibly one more than 20, according to Dan Bennett, TPWD’s district supervisor based in Pottsboro.

“Intensive angler surveys completed in 2019 and 2020 estimated that Texoma striper fishermen catch just over a million striped bass each year and take home about half of those fish to eat,” said Bennett. Those anglers spend a boat load of dough in the process. Economic studies indicate striper fishing pumps around $20 million annually into local businesses.

Amazingly, the fishery is able to maintain that type of output with no outside help from annual stockings, which is necessary to carry some other Texas lakes.

“Catch rates in nets indicate that striper abundance is currently more than 10 times what we see in lakes where stocking is required to maintain the fishery,” Bennett said.

As earlier mentioned earlier, late spring is a great time to catch stripers on topwater plugs. Bennett says the action is generally best early and late but overcast skies may spark a midday bite.

“The fish will school and voraciously feed on spawning shad along shallow shorelines,” Bennett said. “They can be caught just about anywhere. However, good areas to find them are from the dam west to Preston Peninsula along the Texas shoreline, in the shallows around the islands mid-lake, and around Caney and Soldier Creek.”

Anglers may retain 10 per day. There is no minimum length limit, but only two stripers or hybrids may be retained each day. Culling of striped bass and hybrid striped bass is prohibited on Texoma. NO 2: WHITNEY

SIZE: 23,500 ACRES

LAKE RECORD: 39.69 POUNDS

COMMENTS: According to TPWD fisheries biologist John Tibbs of Waco, Whitney continues to benefit from increased inflows from the Brazos and Nolan rivers. This has helped maintain a near constant level, bolstered vital threadfin shad populations and reduced the threat of golden algae blooms.

“Those factors combined with an aggressive approach to stocking, and even some natural reproduction over the past few years, has resulted in an incredible striper fishery— as good or better as at any time in the past,” Tibbs said.

Tibbs said Whitney produces good numbers of box-size keepers in the four- to eightpound range, but anglers do connect with 15- to 20-pounders on occasion. In 2021, the biologist says anglers can look for a lot of stripers just making it to legal size (18 inches).

He added that some of the best fishing usually occurs from mid-lake at the Katy bridge to the dam. Spring hotspots worth a look include the mouth of Cedron Creek, Bee Bluff, Walling Bend Park island and main lake areas near Whitney and Towash Creeks.

Anglers can retain five fish, 18-inch minimum length limit per day.

NO. 3: POSSUM KINGDOM

SIZE: 15,588 ACRES

LAKE RECORD: 34.19 POUNDS

COMMENTS: TPWD Fisheries biologist Robert Mauk says Possum Kingdom has benefited from increased water levels and flows the past few years, resulting in natural reproduction and recruitment, so stocking has not been required. The lake also maintains a bountiful threadfin shad population to help keep the stripers fat and sassy.

Mauk said the lake currently has good numbers with many fish in the 16- to 20-inch size class. Fish upwards of 12 pounds are reported on occasion, but not often.

Soaking live shad is a highly preferred tactic on Whitney, though success can be had on slabs, jig/swimbait combos and topwaters.

“Following working birds is the easiest technique to locate the fish,” Mauk said.

continued on page 22 u