14 minute read

Identifying Plants

The Key to Land's Past, Present and Future

Article by LORIE A. WOODWARD Photo by STEVE NELLE

The plants that exist on a ranch tell the story of the land's past, define its present and portend its future.

“The existing plant community is a visual history of the land and its uses over time,” said Forrest S. Smith, Dan L Duncan Endowed Director of Texas Native Seeds Program at the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute in Kingsville. "On any given day, the plants will tell landowners what successional stage the land is in vegetation-wise."

He continued, "And because the land and the plants, in any given region, respond in a predictable manner to different weather and management techniques, the existing plant community can indicate what the land likely will look like under different management and weather scenarios."

For many people, the allure of working with animals distracts them from the less glamorous but essential pursuit of knowing their dominant plants.

“I run into people all the time, who have a case of 'deer blindness' or 'stock blindness' when it comes to their land,” Smith said. “They only see the animals on the land but don't think it's necessary to pay much attention to the plants."

Disregarding the vegetation can hamstring management efforts.

“Anybody in the business world, whether they're grocers, auto dealers or ranchers, needs to know their inventory,” said Dr. Fred Bryant, Director of Development of the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute who served also as its Executive Director from 1996-2016. “As a rancher or wildlife manager, the plants on the land are a crucial part of the business inventory.”

In the case of a ranch, the existing vegetation is nature's buffet for the animals, whether they're livestock, game or both. Vegetation also provides other essentials such as shelter, nesting or fawning cover, erosion control and more.

“The abundance and quality of plants dictates the abundance and quality of animals,” Bryant said. "If someone doesn't know what's in the inventory it's hard to manage for success."

The quality and vigor of the vegetation also indicates the health of the range and the underlying soil.

“The plant community can be a manager's eyes into the soil,” said Russell Stevens, a wildlife and range consultant with the Noble Research Institute (NRI) in Ardmore, Oklahoma. “What exists above the ground is directly tied to the health and productivity of the soil.”

MOVING ON

While vegetation does not physically move from place to place like roaming animals, the plant community is in a constant state of change.

“The plant community is not static; it's constantly moving in a direction, either forward or backward,” said Bryant. “The direction it's moving tells a person how to manage.”

The cumulative, non-seasonal change in the types of plant species that occupy a given area through time is known as succession. Over time, different plants are colonizing, establishing and disappearing in response to different conditions. Most successions contain a number of stages that can be recognized by the collection of species that dominate the landscape at any given point.

These changing stages or trends in the plant community serve as signals for the observant manager. Fluctuations in vegetation can herald necessary management changes such as increasing or decreasing stocking rates or harvesting more or fewer deer. Trends can also indicate that it is time for an extended rest or that it is time to reintroduce grazing.

“One thing to keep an eye out for is a change in abundance— either an increase or a decrease—of certain plants,” Stevens said.

As one region-specific example, livestock managers in southern Oklahoma and northeastern Texas where the NRI personnel focus their efforts, should pay attention to the increasing prevalence of silver bluestem and purpletop, lower succession grasses.

“In our neck of the woods, when managers see them coming into a pasture that was previously full of higher quality grasses such as big bluestem and switchgrass, it's an indication that there's been a streak of dry weather, that the land management practices have not been successful or both,” Stevens said.

It's important to note, though, that a plant's signal may change with its location, Smith said. In the plant communities endemic to West and South Texas, silver bluestem is an important late serial dominant. In East Texas, purpletop is more highly valued than it is in North Central Texas.

The appearance of new plants, desirable or undesirable, can also trigger a management change. For instance, in South Texas, managers who are interested in maintaining optimum wildlife habitat, should keep an eye out for encroachment by introduced grasses such as buffelgrass and Old World bluestems that can quickly establish and take over native range.

“One season, there may just be a little bit of invasive, introduced grass that's spread from the ditch, and by the next season it may be a well-established stand that is much more difficult to control,” Smith said.

When it comes to invasive grasses, it's important to understand their natural history and lifecycle, Smith said. In some cases, they are actually spread by a disturbance like plowing or burning. Without proper knowledge, managers can actually intensify an infestation by trying to control it. Differentiating these grasses from native grasses can be an important skill for a manager.

On the other end of the spectrum, sometimes a confluence of conditions creates a flush of a desirable plant, such as a legume that had been previously unseen on the land. In that case, managers might want to tweak their strategies so the plant is encouraged to re-establish, Stevens said.

“Most land management above the surface is typically about manipulating plant communities…having more of this and less of that,” Smith said.

Ultimately, the manipulation is driven by the manager's goals for the property.

“Every plant contributes something to the landscape, even if it's just helping control erosion or creating a microclimate in the soil that ushers in the next successional stage,” Bryant said. “A plant's relative value to individual managers depends on their management goals and objectives.”

Croton offers a good example. For managers who are interested solely in livestock, the emergence of croton, which has low palatability for cattle, is not a harbinger of good things. For people who are creating habitat for game birds, croton,

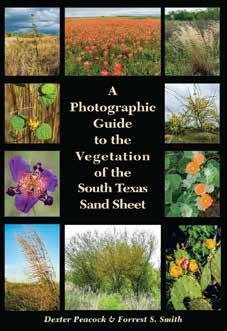

BREAKING NEW GROUND A Photographic Guide to Vegetation of the South Texas Sand Sheet

A Photographic Guide to the Vegetation of the South Texas Sand Sheet, published by Texas A&M University Press, exists because Dexter Peacock struggled to identify the plants on his Hebbronville ranch.

“While other field guides are available, they are written with botanists and other scientists in mind—and none of them are focused to the Sand Sheet region,” said Peacock, noting most guides are built around taxonomic keys, scientific names and dedicated to a single group of plants such as grasses.

“As a rancher and a hunter, I wanted to learn more about plants so I could improve the habitat on my land, but the lack of accessible information was frustrating,” Peacock said.

At the time Peacock began trying to identify plants, he amassed a collection of 14 or so books about the plants in South Texas or adjacent areas, but none were an all-encompassing plant guide useful in the Sand Sheet specifically. The existing plant identification resources took a decidedly scientific bent in content and organization. Peacock is a retired Houston attorney, rancher and avid photographer.

“I thought that identifying my plants would be like researching a legal problem,” Peacock said. “I assumed I could just keep searching until I found the answer.”

When the answers weren't forthcoming, Peacock decided to solve the problem himself. He enlisted the expert assistance of Forrest Smith from CKWRI.

which produces highly palatable and nutritious seed, is a desirable addition to the landscape. In fact, some people create the disturbances necessary to encourage its growth.

PUTTING A NAME TO IT

Of course to identify the vegetation trends and how they fit into their overall management goals, managers must be able to identify key plants.

“Putting a name on a plant unlocks the gate to the other pertinent information such as its values and its lifecycle,” Smith said.

Because many people view plant identification as an all or nothing proposition, they are often intimidated by the prospect of learning the plants on their land.

“Land managers don't need to know every plant on their property—and it's not a reasonable expectation that they will,” said Smith, noting he encounters new, unknown plants every time he sets foot on the land.

In Smith's estimation, land managers, in any given region of the state should strive to learn the most important indicator plants in their specific location. These indicator plants provide clear insight into what is going on within the ecosystem, and anyone who can recognize them will have a functional working knowledge that will move them further, he said. In general, these include the most palatable and unpalatable grasses, key forbs and legumes for target species, and invasive species such as non-native grasses, undesirable brush or problematic weedy forbs.

Stevens simplifies the process even more. As a starting point, he suggests that land managers familiarize themselves with 10-15 of the most dominant grasses, forbs, woody shrubs and trees on their land.

“In my experience, you don't have to read the whole 'library' of available plants to understand the land's story,” Stevens said.

For people who want to familiarize themselves with plants that could be common in their area, Stevens suggested starting by looking up their specific ecological site on the NRCS website. The ecological site description includes, among other things, the plants that likely occur at various ecological stages.

“This gives beginners an idea of what they might encounter, so it's a starting point to hang their research on,” Stevens said.

Identifying plants, at least for the most common species, has gotten easier thanks to technology. Smartphone apps such as iNaturalist and PictureThis provide fairly accurate identification for relatively abundant plants.

“Many of these apps use artificial intelligence, so the more entries and expert feedback a plant has gotten, the more reliable the identification is,” Smith said. “The apps work pretty well for common plants or for areas with accessible natural areas so that a large number of observations have been made, such as near large urban areas. But they're not going to help you much if you get off the beaten path.”

With or without the apps, a smartphone with a camera can be a definite asset for fledgling (or experienced) plant enthusiasts. All three range professionals suggested taking photos of an unknown

“We set out to create a user-friendly field guide that was equally at home in a graduate student’s backpack, on a rancher’s dashboard, or on the seat of a quail rig,” Peacock said.

They succeeded—and Texas A&M University-Kingsville sponsored the guide’s publication through the Perspectives on South Texas Series.

“We collected the majority of the region’s common plants in one book—and arranged them in a way that should make sense to people on the street,” Smith said. “To that end, we grouped like things together such as grasses with similar appearance and flowering plants with the same color blooms.”

In the guide’s 231 pages, readers will find information on more than 200 common plants organized by type: grasses (including native and invasive grasses), forbs and wildflowers (subdivided by color), shrubs (subdivided by presence or absence of thorns), trees, cacti and vines.

Knowing that a clear picture is worth a thousand scientific explanations, the duo used photographs of the various plants as the primary means of identification. The guide contains 365 color photos taken by Peacock and Smith.

“In many cases, we have several photographs of a plant showing how it might look from a distance, up close, and at different stages of its life cycle during different times of the year,” Smith said. “Using the photos, it’s possible to accurately identify a plant within minutes.”

The guide provides the scientific and common name of each plant, as well as regional names including those in Spanish. For instance, sand verbena, a well-known wildflower that grows near Falfurrias, is known locally as heart’s delight, and spiny hackberry is known locally as granjeno.

The user-friendly guide sold out within 90 days of its first printing in November 2019. (Currently, it is intermittently available on Amazon.com.) A second printing is expected to be available in April 2021.

The enthusiastic reception validates the usefulness of the groundbreaking guide's intuitive organization.

“A resource guide is only valuable if people can and do use it,” Smith said.

Using the Sand Sheet guide as a prototype, a group that includes Peacock and the Wildlife Habitat Federation in Cat Spring along with many others, is working on a guide for the Upper Texas Coast. Discussions are underway for a Piney Woods regional guide.

“The vegetation dictates whether you can profitably ranch, what wildlife you’ll find and what condition they will be in— and from an asset point of view, the plants directly impact the economic value of the land,” Smith said. “Successful management of all these resources begins with knowing the plants. If we want more people to learn about plants, then we need to make more user-friendly resources available.”

plant, including close up pics of its leaves, flowers, seed head and any other defining characteristics. These photos can then be shared with professionals at a host of agencies including Texas A&M AgriLife Extension, USDA NRCS, universities and NGOs such as NRI.

“It's what we're here for,” Smith said.

In the digital era, photos have replaced traditional plant collections for most people. These days, it's possible to carry a personal plant collection in a shirt pocket. Most herbariums have digitized their collections, which makes rare and unique plants widely available on the Internet.

According to Smith, one of the best is the Billie Turner Plant Resources Center at The University of Texas-Austin. While the herbarium is housed in the UT Tower, scans of plant mounts in the collection can be viewed for free online. The scientific name of the plant in question has to be known, but the collection can also be browsed by county.

Books are the traditional go-to resource. While they are considered the gold standard of information, they, especially those based on taxonomic keys, can be frustrating for non-botanists. And depending on the ecoregion, it may take a host of resources to provide an accurate picture of what is there.

For most people, it is helpful to seek out books that contain photos. Be aware that many books feature plants in only one season of the year, so it may be hard to accurately identify a plant if it's in a different stage of growth.

“Books are great resources, but they have their limits for most people because of how they tend to be organized,” Smith said.

One of the most effective ways to learn about the local plant community is to walk alongside someone who knows plants.

“It doesn't matter whether it's your local agency professional or a knowledgeable neighbor, getting on your land and talking with someone about the plants you're seeing is a valuable investment of time,” Bryant said.

While vegetation may not have the charisma of animals initially, plants often become addictive to those managers who take the challenge of unlocking their potential.

“Once you really get into identifying plants, it's easy to get hung up and not know when to quit,” Stevens said. “As you learn more, it becomes a fun, challenge to drill down on the real 'nasties'—the odd, unique plants that just show up out of nowhere and disappear in a flash. As a manager, the more you know, the more effective you become.”

Editor’s Note on plant identification

for the deer manager: In the October 2020 issue of Texas Wildlife, Steve Nelle’s article “Deer Habitat with Class” discusses the common food plants preferred by deer. Sidebars within that article list most desired to least desired in each Texas region, and some of the plant species photos are included for identification purposes as well. You can access that article online at https://issuu. com/texaswildlifeassociation/docs/202010-october_proof4_final/s/11073001.

TWA Auction Success

LOOKING FOR A HUNT OR TRIP OF A LIFETIME? WILDLIFE 2021

IS THE PLACE TO FIND IT!

JULY 16-18, 2021

JW Marriott San Antonio Hill Country Resort and Spa 23808 Resort Parkway, San Antonio, TX 78261

Thanks to TWA Life Members Joseph and Blair Fitzsimons as well as Dr. Chase Currie at the San Pedro Ranch, TWA Member Al Almanza and his son Brandon (pictured here) had the whitetail hunt of a lifetime this past season. Exclusive hunts like this are some of the many exciting items you’ll find at this year’s WildLife 2021. TWA’s Annual Convention will be held July 15-18 at the beautiful JW Marriott San Antonio Hill Country Resort and Spa. A portion of the auction will be held online again this year.

(A portion of this year’s auction again will be conducted online.)

FUN FOR EVERYONE!

EXCITING AUCTIONS WITH EXCLUSIVE HUNTS AND TRIPS! TOP NOTCH TRADE SHOW!

COME SEE ALL YOUR FRIENDS! TEXAS BIG GAME AWARDS STATEWIDE CELEBRATION ANNUAL PRIVATE LANDS SUMMIT

JULY 15-18, 2021

Bring the family! Children 12 and under are admitted FREE! Visit WWW.WILDLIFE2021.COM or call (800) 839-9453 for more information