Recently, I found myself digging back through archived copies of “Texas Wildlife” magazine and even earlier copies of the “TWA Newsletter.” I had a blast seeing pictures of old friends and reading articles about organizational successes like the passage of Prop 11 and the early days of currently recognizable programs like the South Texas Wildlife Conference and Texas Big Game Awards. Once I finally made myself stop thumbing through old magazines and get back to work, a couple of things stood out to me.

Several of the TWA members pictured in those early issues are still around and contributing at an important level for the organization. What is exciting to me is that some of their kids are now assuming leadership roles and making their own meaningful contributions. At the director’s meeting March 2 in Alpine, there were multiple secondgeneration TWA members in attendance who are now serving in leadership roles.

While I can’t be sure of everyone’s stories, I know that at least a couple of those secondgeneration TWA leaders began developing their love for the organization by attending TWA Convention with their parents each summer. My daughters love coming to Convention and I would encourage you to bring your children, too.

Several of the issues we are working on today have popped up before. In some instances, multiple times. For example, in an article covering the third-ever South Texas Wildlife Conference from October 1990, back when the Texas population was around 17 million, then-TPWD Executive Director Andy Sansom talked about the department’s challenges meeting the public access demands of a growing Texas population. Just three years ago at the TWA Private Lands Summit, TPWD State Parks Director Rodney Franklin shared a similar message with the crowd, only this time dealing with a Texas population of more than 30 million, reporting on the massive increase in state parks usage during and after the COVID pandemic.

I also stumbled upon an article from January 1996 about a petition submitted by the Sierra Club to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission requesting that mountain lions be considered game animals. In January 2024, the Commission received a briefing from the mountain lion stakeholder committee that was formed in response to a petition they received in the fall of 2022. After review and consideration of research findings from the previous five years, the petition was ultimately denied.

While the most recent lion petition was ultimately denied by the commission, most of the items were given serious consideration. In fact, the commission is set to take action on a regulatory proposal at its May meeting that would ban canned mountain lion hunts and institute a 36-hour trap check requirement for lion traps.

My little history lesson with the old magazines served as a great reminder that we need to occasionally look back at the past to make sure we get it right for the future. TWA has been a leader in land stewardship, landowner rights, and hunting recruitment for a long time. With your continued support and engagement, we will continue to be long into the future.

Thanks for being a TWA member.

MAY 6

Land, Water & Wildlife Expedition, San Antonio, Texas. For information, contact Gene Cooper at gcooper@texas-wildlife.org or call 800-TEX-WILD (800-839-9452)

MAY 16

TWA & Duck Camp Shirt Release Party. Austin, Texas. For information, contact Kristin Parma at kparma@texas-wildlife.org or 800-839-9452

MAY 17

TWA & Duck Camp Shirt Release Party. Houston, Texas. For information, contact Kristin Parma at kparma@texas-wildlife.org or 800-839-9452

MAY 17

Land, Water & Wildlife Expedition, Floresville, Texas. For information, contact Gene Cooper at gcooper@texas-wildlife.org or call 800-TEX-WILD (800-839-9452)

MAY 21

Adult Learn to Hunt Wild Game Dinner and Fundraiser, Barrow Brewery, Salado, Texas. Contact Jim Wentrcek for information at jim@firsttexas.com

JULY 11-14

WildLife 2024, TWA’s 39th Annual Convention. For more information visit https://www.texas-wildlife. org/wildlife-convention/

JULY 12

TWA Foundation Luncheon. Join us for this special event as we honor Larry Weishuhn for his lifetime of contributions to hunting, conservation, and the Texas Wildlife Association. Tickets and tables available at https://secure.qgiv.com/event/ strfyy/

JULY 27

Texas Big Game Awards Celebration & Conservation Film Tour, Bryan, Texas. For information, contact Kristin Parma at kparma@texas-wildlife.org or 800-839-9452

AUGUST 17

Texas Big Game Awards Celebration & Conservation Film Tour, Fort Worth Community Arts Center, Fort Worth, Texas. For information, contact Kristin Parma at kparma@texas-wildlife.org or 800-839-9452

Would you like to spend your lunch break learning about wildlife management? Join us for our FREE monthly program, “Wild at Work: A Stewardship Series.”

Wild at Work’s are one-hour long webinars scheduled from noon to 1:00 p.m. on Wednesdays to give working people a chance to virtually attend. These webinars will cover a variety of topics concerning everything from private land stewardship to Texas wildlife management to natural resource policy updates. Topics planned for the remainder

of this year include conservation easements and mitigation banking, North American model of wildlife management, and natural resource legislation updates.

Date and Time: Second Wednesday of every month | noon – 1:00 p.m. with time for live Q&A

Who: Variety of speakers from Wildlife Biologists to Natural Resource Lobbyists

Cost: Completely FREE (Donations are helpful)

Contact Jared Schlottman at jschlottman@texas-wildlife.org or 512-350-5563 for more information

or visit https://www.texas-wildlife.org/waw/.

Details on future webinar dates/ topics will be forthcoming.

Photo by Will Leschper

Photo by Will Leschper

Deer hunting is a prime pastime for hundreds of thousands of Texans each fall and winter for many different reasons. These include the opportunity to take in the glorious sights that time of year and spend special time with family and friends. If you look closely at the right side of this buck’s antler frame, you’ll notice an “acorn” point, which occurs when a buck brushes up against something as its antlers are developing in velvet.

Whitetails Mean Big Bucks in More Ways Than One

Article by WILL LESCHPERDeer hunting in Texas is more than just a barrage of camouflage.

For many folks — hundreds of thousands in the Lone Star State alone—deer hunting is life. From Amarillo to Brownsville north to south, and Texarkana to El Paso east to

west, across numerous varied ecosystems all with their own geographic nuances and allures, it’s easy to see why.

Deer hunting is big and booming business.

Deer hunting is time-honored tradition.

Deer hunting is simply time spent afield unlike any other.

And that means camo isn’t the only green that Texas deer hunters spread across the state. Approximately 555,000 hunters spend a total of nearly $2 billion each year on white-tailed deer hunting pursuits in Texas while 200,000 landowners spend about $2.5 billion. All together, Texas deer hunters provide an almost $10 billion total economic boost to the state.

Beyond the emotions and motivations associated with enjoying the hunt, which can vary and are hard to assess because they are subjective, an inspection of the numbers reveals just how significant the impact is. It’s especially true at the local level.

Places like Llano, Junction, and Mason are just a few of the many dozens of small towns across the state that welcome hunters with open arms. That often means wild game dinners and hunter appreciation events complete with barbecue, all the trimmings and plenty of prize giveaways underwritten by local businesses and residents who all enjoy sharing in the land of plenty that hunting continues to provide.

Local business owners love seeing GameGuard®, Realtree® and Mossy Oak® from head to toe, pickups and SUVs towing gear-laden trailers, and all those hunters and their families who bring along their wallets. It begins with lease preparations in September and ends in January and February.

Those dollars flowing into many communities can make the entire year for small shops. It’s especially true for those who were hit hard and perhaps still recovering from the pandemic, which was compounded in recent years by Mother Nature’s conditions making hunting a bit tougher, bringing in fewer visiting hunters.

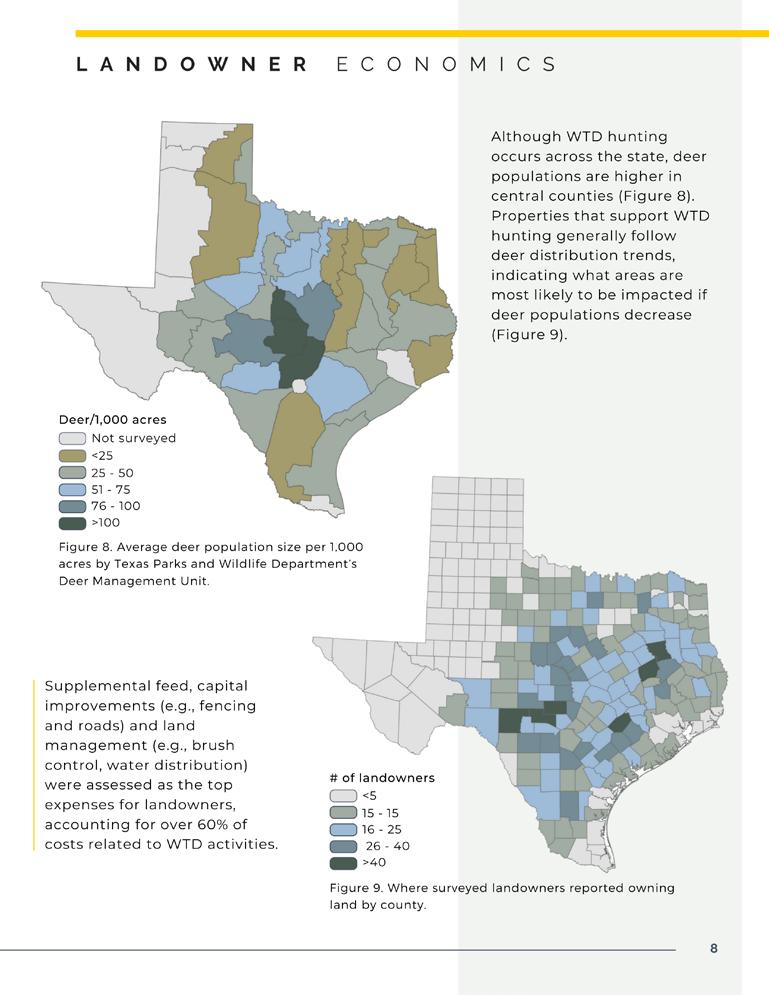

A recent survey conducted by the Texas A&M University Department of Rangeland, Wildlife and Fisheries Management and the Texas A&M Natural Resources Institute helps shed light on just how valuable white-tailed deer are to the state of Texas economy. The project was carried out in 2022 and 2023 with the first part of the survey results released to the public in May 2023.

An online survey was sent to a random sampling of 100,000 Texas super-combo license holders. Respondents were divided into two groups, either a hunter or a landowner. In total, roughly 9% of the total responded to dozens of distinct survey questions about everything going into their pursuit from their most recent deer hunting season.

Using survey estimates as a baseline, researchers then extrapolated the total statewide financial impact of hunters and landowners. Here’s a sampling of interesting facts compiled from the first part of the study, which centered on expenditures, as well as profile data for each group:

• There are approximately 5.3 million wild deer in Texas and about 103,000 deer in breeding facilities permitted by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

• Approximately 555,000 hunters spend nearly $2 billion each year as a whole on white-tailed deer hunting pursuits

in Texas, while 200,000 landowners spend about $2.5 billion.

• The top five most common expenditures for hunters are licenses, transportation, meals, shooting equipment, and feed/feeders. The five largest are outfitter/guide fees, lease fees, lodging, land management, and feed/feeders; the average lease fee was $2,904 and each hunter spends a total of $3,348 annually on deer hunting.

• More than half (52%) of hunting land owned by family or friends. Another portion (41%) hunt on leases and the rest use public land (5%) and outfitters (2%).

• Landowners spend an average of $18,812 and bring in $20,658 in revenue. The top five most common expenses are supplemental feed, property taxes, land management, equipment maintenance, and capital improvements. The five largest are payroll, land management, supplemental feed, hospitality, and property taxes. Landowners spend an average of $3,593 per year on supplemental feed.

• The vast majority of landowners (95%) described their deer herds as “100% native” with no influence from introduced deer from breeders.

• About 70% of Texas deer hunters do not own land, and 45% of those hunters reported leasing land or hiring outfitters to deer hunt.

The results from the second part of the joint Texas A&M survey were released in November 2023, just in time for another deer season, and centered on direct economics involving hunters and landowners. Estimates from that portion of the survey also yielded many pertinent figures, including just how huge the Texas deer hunting impact has at the local, state, and even federal level:

• Texas deer hunters generate an estimated $4.6 billion in total economic output each year while landowners who support deer hunting generate about $5 billion in annual economic output.

Deer hunting is a three-month season that most average hunters — and again, there are hundreds of thousands of us — look forward to the instant we leave a lease for the last time in January or February, closing the book on more invaluable memories as we close that ranch gate.

Make no mistake, deer hunting success is based on multiple criteria centered on your own personal preferences.

Perhaps you only count achievement by the number of tags you fill or the weight of the delicious, organic venison you put in the freezer to provide for your family and friends who may not hunt, but certainly enjoy the gifts of your efforts.

Maybe you only hunt for the antlers or for taking only mature bucks, those animals that already have helped to spur on multiple generations of future whitetails and have proven to be the epitome of healthy, native deer.

No matter your inclination, there is no wrong answer in determining success in the deer woods, forests, mottes, canyons, or plains of Texas where Texans are blessed to pursue our state’s prime big game animal.

And if you’re like most hunters, myself firmly entrenched on this hill, deer hunting is mainly an excuse to spend time outdoors alone or with family and friends, across any pristine landscape here in the Lone Star State, joining others in the shared search of our state’s number one hunting opportunity.

• White-tailed deer hunting supports 23,726 jobs resulting in $1.3 billion in labor income and $446 million in annual tax revenues ($237 million federal, $114 million local, and $95 million to the state).

• Each hunter has an average economic impact of about $6,000 per year while hunters spend an estimated $462 million on travel while deer hunting.

• Beyond the jobs mentioned above, landowners who support deer hunting employ about 35,000 people, provide $707 million in labor income, and generate more than $90 million in tax revenue ($60 million federal, $31 million state and local).

Think about how many pallets of bagged corn change hands over the course of the year—and that’s just one small aspect of the pastime—and you can begin to envision the wide-ranging scope of Texas deer hunting.

All that funding has a trickle-down effect, helping pump hundreds of millions of dollars into the local and state economy each fall and winter. While that dollar amount includes valuable funds headed to outfitters, mom-and-pop shops, and those making a direct living off the hunting industry, the federal taxes generated by the overall industry end up going back into state coffers earmarked for needed resource protections and improvements.

# of hunters

c:::J <75

c:::J 75 - 50

c:::J 57 - 700 - 707 - 250 ->250

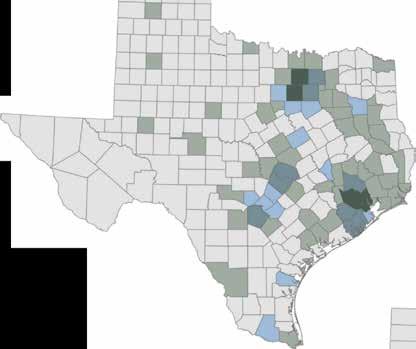

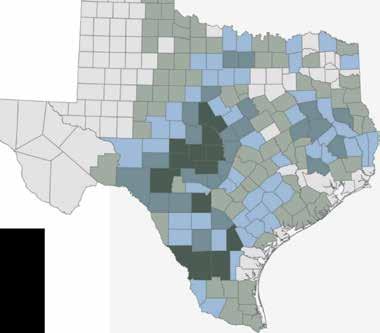

7. Where surveyed hunters reside by county.

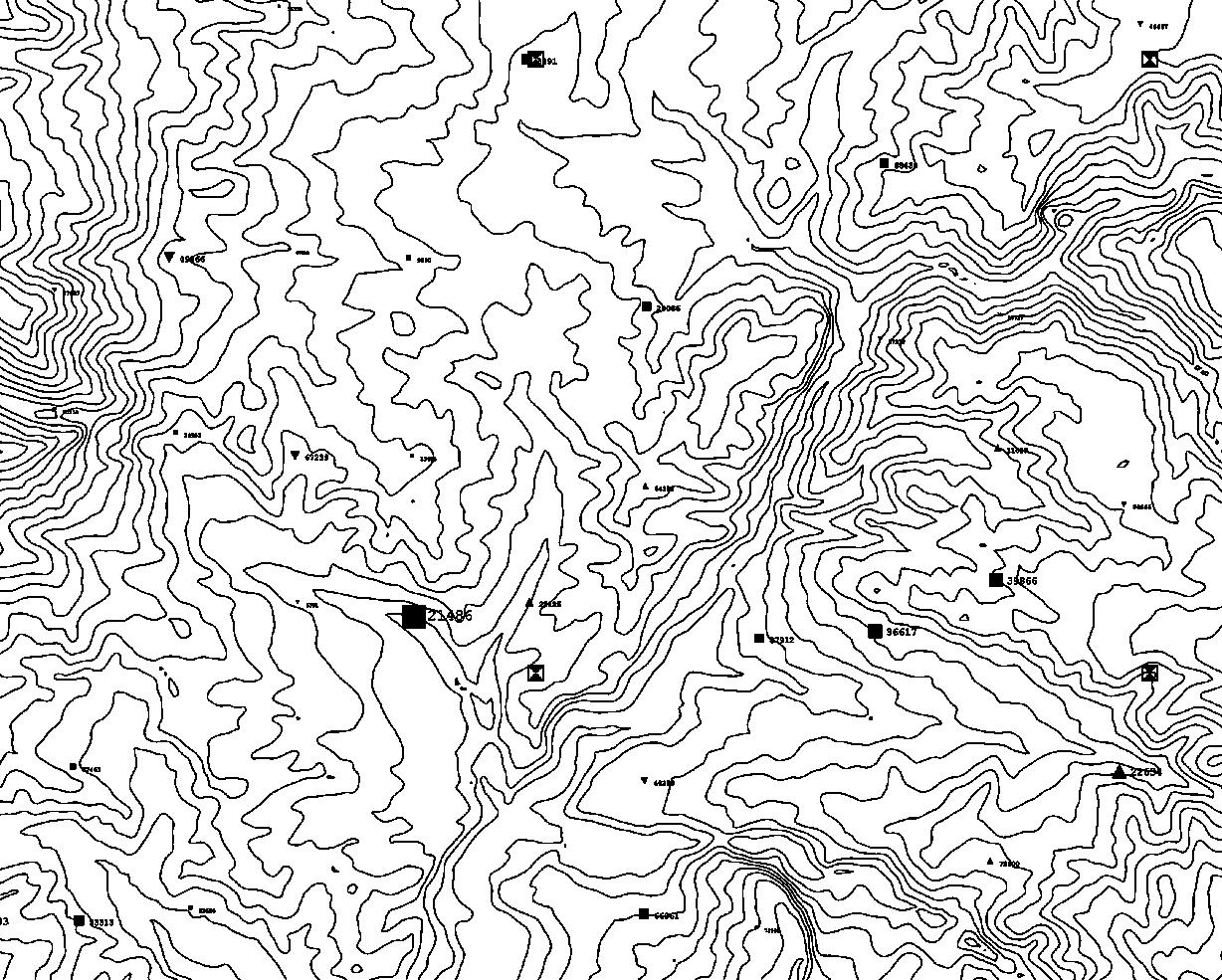

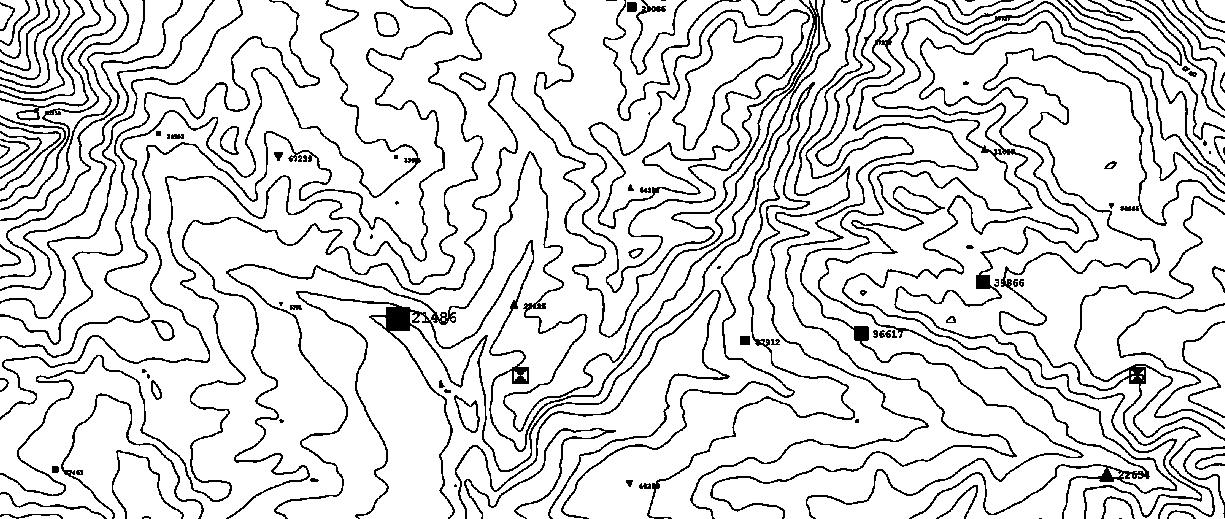

Survey results indicate the majority of hunters reside in the state's four largest metropolitan areas-San Antonio, Austin, Da I las-Fort Worth and Houston -whereas the majority of hunting occurs in rural, centra I counties. With nearly $462 million spent on travel alone, rural areas benefit from the revenue brought by WTD hunters (Figures land 2).

Travel expenses (meals, lodging, and transportation) were among the most common expenditures reported by hunters. Figures 3-6 show the extent to which surveyed hunters travel to participate in WTD hunting.

# of hunters

c:::J <70

c:::J 70 - 25

c:::J 26 - 40 - 47 - 60 ->60

In that aspect, hunting is conservation, with a direct correlation to improving habitat and in some cases access and opportunities.

The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service annually distributes revenue to each state’s wildlife agency through the Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration Act, with funds coming from excise taxes on the sale of everything from sporting firearms and ammunition to archery equipment.

That figure in 2023 coming back to the Lone Star State was nearly $55 million for wildlife restoration efforts—the highest figure in the country. Pittman-Robertson funds allow the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department’s Wildlife Division to offer many services, including technical guidance to private landowners who control roughly 95% of wildlife habitat in Texas, TPWD surveys and research for development of hunting regulations, operation and management of wildlife management areas, and conducting research and developing techniques for managing wildlife populations and wildlife habitat.

Hunters also play a vital role in deer management at the statewide level, which also means a lot. Those hundreds of thousands

of hunters are the main mechanism by which TPWD influences overall deer numbers, buck-to-doe ratios and various herd genetics, while helping to increase or reduce populations based on selective harvest.

The clear example of this conservation role and management framework is the antler restriction regulation implemented in a half dozen Post Oak counties in the late 1990s. They were designed to improve the age structure of buck herds, increase the opportunity to harvest those bucks and encourage better habitat management. For the most part, that framework has been wildly successful, and the restrictions are now in place in many more counties in the Post Oak, Piney Woods and northern Coastal Prairie regions. While it’s easy to quantify the economic and management impacts of what deer hunting means to Texas, it’s just as simple to see numerous other ways hunters contribute. In many regards, deer hunting also is about giving back, whether it’s hunting organizations and local clubs offering community fundraising events and field days that get families into the outdoors— something that’s vital to our hunting heritage—or providing high quality, lean meat for the state’s Hunters for the Hungry program.

Alan Cain, current big game program director and longtime former TPWD deer program leader, may have the best answers on quantity and quality when it comes to both deer hunting and enjoying the outdoor pursuit in general.

“Regardless of where you hunt in Texas, there’s always a good chance you’ll see a great, quality buck each season,” he noted. “Whether you take a deer or not, spending time outdoors with your family and friends is worth the effort, much better than spending a day at the office or a weekend on the couch.

“Hunters ought to feel lucky that we live in Texas with the largest deer herd in the nation. Our biggest problem is that we probably don’t harvest enough deer. If hunters and landowners are unsure about how many deer they should harvest on their lease or ranch, consider contacting the local TPWD wildlife biologist (www.tpwd.texas.gov/landwater/land/technical_guidance/biologists) to discuss possible deer survey options and deer harvest recommendations,” he said. “Establishing a population estimate on the hunting property can help hunters better manage the deer herd in their localized area and meet deer or hunting management goals.”

“I now realize that I had always wanted to own land and to study and enrich its fauna and flora by my own effort. My wife, my three sons and my two daughters, each in his own individual manner, have discovered deep satisfactions of one sort or another in the husbandry of wild things on our own land.”

~ Aldo Leopold,

1947

Aldo Leopold and his wife Estella purchased their “farm” in 1935. They and their five children had always enjoyed the land together and developed a love of hunting, fishing, bird study, botany, exploring, and general outdoor activity and appreciation. Up to that time, their enjoyment came from public land or someone else’s land. But ask any landowner and they will confirm that owning and managing your own land is different, deeper, and more satisfying than doing the same things on someone else’s land.

With their growing interest in hunting and the desire to have their own place, Leopold found his “worn out farm” alongside the Wisconsin River about 60 miles from their home in Madison.

Theirs was not a farm in the traditional sense.

The modest tract had once been working farmland but due to drought and poor farming methods it was depleted, unproductive, and was abandoned by the previous owner. The hoped-for products from the Leopold farm were not crops, livestock, or commercial timber, but wild things and personal enjoyment.

Notice the order of activity described by Leopold after he became a landowner. The first priority was to study the land. Only after careful study and some degree of understanding can a landowner see well enough to know what the next steps should be. Opportunities then become apparent for ways to enrich the plant and animal life, and this requires effort. That is the essence of land management or what Leopold sometimes called “intelligent tinkering.”

Too often, we skip over studying the land and go right to managing it. But Leopold emphasized that study and comprehension of the land should always precede any efforts to manage the land. Because each tract of land is different and unique, its own character and capability must be discovered before the appropriate management becomes clear.

The Leopold farm’s headquarters was called “the shack,” a converted chicken coop left over from the past. The shack

was enlarged and improved over time to accommodate sleeping, cooking and mealtime. Although simple and crude, it became their home on weekends and holidays. Leopold’s daughter Nina said, “The shack was everything but it was nothing.” Their work on the shack and the farm and the time spent together helped cement their close relationship as a family.

Leopold, his wife and children each developed their own unique interests at the farm and these interests fueled and inspired their future directions in life. All five children became leaders in the field of natural resources and made significant contributions to conservation.

Leopold’s farm was only 150 acres and this reminds us that a deep, abiding connection to the land does not require large landholdings or multi-generational ownership. The people-land relationship can develop on small or large tracts.

The key is not the property’s size nor how long it has been in the family. The key is the time spent on the land observing, studying, discovering, analyzing, experimenting, working, succeeding, failing, and persisting. The lessons learned over the years at the farm are in large part the subject of Leopold’s masterpiece, “A Sand County Almanac.”

For the Leopold family, the key benefit of owning the land was not in the quality or quantity of hunting or the number of plant or animal species, or any such measure. The end result is described simply as “deep satisfactions” derived in the husbandry of wild things. Husbandry is a word that has fallen out of common use, but it means precisely the same thing as stewardship—loving the land and taking responsibility for her care and protection.

Wild things can be just as much of a “crop” as agricultural products and can be produced in abundance alongside traditional farm crops. Both traditional crops and wild crops require skill, commitment, and husbandry.

WRITER’S NOTE: Aldo Leopold (1887-1948) is considered the father of modern wildlife management. This bi-monthly column will feature Leopold's thought-provoking philosophies as well as commentary.

Statistics and photo courtesy of CONSERVATION LEGACY

* Participation numbers from out of state participants and/or virtual learners whose location was not collected.

“Wanna come up and go with me?” asked Luke Clayton, co-author of our recent book, “Campfire Talk.”

“Depends whether you’re talking about hunting or fishing…come to think about it, maybe we do both,” I said, knowing most of our East Texas counties have a May 1–May 31 squirrel season. “You know one can’t live on venison alone.”

“Sounds like a plan,” he said. “You hunting with a .22 or a shotgun? I’ll bring what you don’t.”

Luke’s question brought back many squirrel hunting memories from decades earlier when I hunted squirrels with my maternal granddad. As a 4-year-old, I

used a Daisy Red Ryder BB-gun. Squirrel hunting back then was huge throughout the eastern third of our state. Deer were scarce, but we did have a lot of gray and fox squirrels.

Attaining the grand old age of 6, I was given a choice to hunt with a Winchester .410 single-shot or my granddad’s Remington .22 single-shot. I chose the .22.

On early squirrel hunts after “Hunter,” my grandfather’s mixed breed squirrel dog, treed a squirrel, it was my job to walk around to the other side of the tree of where my granddad waited, causing the squirrel to show itself. Treed squirrels generally kept the tree trunk between them and someone on the ground looking for them.

I was taught to shoot squirrels behind the shoulder rather than in the head. Doing so brought the squirrel down with little loss of meat, for indeed they were hunted for “pot and table.” Plus, Great Grandpa Meyer wanted the squirrel heads, which he left intact when he cooked squirrel stew.

When the stew was ready to eat, he would use a big spoon to crack open the skulls and eat the brains. Squirrel brains were considered a delicacy. Nowadays, that sounds a bit primitive, but back in the early 1900s and likely earlier, it was a standard practice when cooking squirrels.

“Been told it was the same back in northeast Texas,” Clayton continued when I told him about the practice. “I’ll bring a .22 that I’ve used a lot on squirrels.”

“I’ll bring my little Mossberg .410 over/ under shotgun,” I replied.

Clayton and I decided to do a short hunt 2 miles from his northeast Texas home. There we hunted spot-andstalk and sit-and-wait. While doing so, I remembered an article John Wootters wrote in “Petersen’s Hunting” magazine years ago titled “Treetops Whitetails.” Wootters described sitting and watching treetops and the ground where squirrels foraged for food and finding knotholes indicating hollow trees where squirrels lived.

Hunting squirrels, according to my old friend, created a hunter who was

observant and patient, two attributes that not only helped take squirrels but also made one a better deer hunter. He coupled this with accurate shooting.

Clayton and I headed different directions. Several minutes later I heard a shot, five minutes later, another. Earlier I harvested a squirrel on the ground, and a second immediately after that came out of a knothole. The daily bag limit was 10, but two each would be sufficient. Some counties do not have a bag limit.

We both had taken a young squirrel destined for a cast-iron frying pan. The two older males would be tough. They were the key ingredient in a tomato, onion, and potato-based stew. If you are not hunting squirrels, you should. They are abundant, fun, economical, and delicious. Spending time in the squirrel woods also makes you a better deer hunter. That indeed is a good combination.

Scaled quail (Callipepla squamata) is a species susceptible to seasonally limiting environments. Occupying grassland-shrub habitats of the Chihuahuan Desert and its adjacent regions, scaled quail hold ecological and economic significance as a prey item in grassland trophic communities and as a contributor to local revenue through hunting. Unfortunately, scaled quail have experienced declines since the 1960s, primarily due to habitat degradation from historic overgrazing and changing land use practices.

Scaled quail populations are heavily influenced by precipitation, driving vegetation growth that supports reproduction and survival. This effect is tied to the boom-and-bust population trend for scaled quail, where populations increase following above-average rainfall and decline during drought. The scaled quail’s ability to maximize the benefits of rainfall and withstand drought is compromised when the habitat becomes degraded.

Desertification, woody shrub encroachment, and invasive grasses have altered the magnitude of the positive and negative conditions scaled quail experience. This makes population “booms” less eruptive and population “busts” more severe, resulting in declines.

Habitat quality becomes critical in resource carryover from the growing season into winter. Chihuahuan Desert winters are characterized by low moisture, reduced plant growth, and periodic winter storms. This presents scaled quail with reduced food and cover amid occasional extreme temperatures, increasing predation, starvation, and climatic exposure risks.

As native grassland-shrub ecosystems are degraded, the impact of these challenges increases, exaggerating seasonal limitations beyond scaled quail’s adaptive tolerance. This raises questions regarding how scaled quail respond to this challenging seasonal period.

Literature on other quail species suggests habitat selection and movement behaviors reflect their responses to winter conditions. Monitoring these behaviors has captured reduced movement during winter storms, use of supplemental resources, and selecting microhabitats that enhance habitat quality.

Such monitoring could similarly capture scaled quail’s response to winter conditions and identify properties of their preferred winter habitats. Unfortunately,

little research attention has been paid to scaled quail’s spatial behavior during Chihuahuan Desert winters.

We monitored scaled quail in southern Brewster County, Texas, during the winter 2022-23 to describe their spatial response to winter landscapes. We fitted 37 scaled quail with backpack-style Global Positioning System (GPS) tags that collected a GPS location every two hours during daylight hours, giving us eight GPS locations daily.

These locations and the movements between them were then described using their underlying environmental variables. These include topography, vegetation greenness, distance to the nearest supplemental feeder, and ambient temperature.

Scaled quail selected for supplemental feeders, moderate values of greenness and slope, and concave landscape features such as drainage features during winter. Vegetation greenness had the largest effect on selection, as increases in greenness increased the odds of scaled quail selecting a location.

Movement behavior was impacted by distance to a quail feeder, which tended to reduce movements as scaled quail were closer to a feeder. Interestingly, our results do not suggest scaled quail’s movement behavior was affected by cold temperatures. However, this could be a product of a mild winter and the coarse resolution of our climate data.

The effect of quail feeders on movement could suggest they offer fitness benefits. Winter food shortages prompt quail to expand their ranges and expend more effort locating food, producing energy deficits, and increasing the risk of detection by predators.

Reduced movement near feeders suggests access to supplemental feed reduces feeding effort, improving foraging efficiency and reducing exposure to predators. While this infers fitness benefits, we did not examine the direct impact of feeders on survival in this study.

Despite low vegetation greenness during winter, scaled quail expressed a strong selection for moderate values of available greenness. As greenness measurements can represent a combination of vegetation vigor and density, this finding is consistent with scaled quail’s known habitat preferences. The highest greenness values observed in our study represented dense brush stands, which scaled quail generally avoid due to their preference for lower shrub densities and sufficient bare ground to allow movement on foot.

Scaled quail’s high selectivity for optimum greenness values reveals the importance of residual vegetation during winter, as high selection strength for a resource often reflects its low availability. It follows

that habitat degradation could have its highest impact during winter, manifesting in extreme resources reductions following winter vegetation phenology. This illustrates the importance of land use practices that conserve vegetation reserves during growth periods, as this helps secure habitats for scaled quail in winter.

Selection for drainage features reveals the topography’s influence on winter habitats. Many of scaled quail’s optimum greenness values overlaid hydrologic features on the study site. Features that concentrate runoff often can enhance habitat quality in desert ecosystems where moisture is limiting.

Greater vegetation growth along these features makes them conducive to greater carryover of food and cover into winter. Thus, drainage features could constitute microhabitats that improve habitat quality from the surrounding landscape.

Literature suggests microhabitats are becoming critical for the persistence of many species facing threats of habitat deg-

radation and changing climate. Hydrologic features could similarly facilitate microhabitats that support scaled quail amid the degradation of their native habitats.

Our results suggest land use practices that retain native grassland-shrub habitats can support scaled quail during winter. Such practices include light to moderate grazing, brush management, and invasive grass control. Additionally, providing supplemental feed in concert with habitat management could help mitigate the energy limitations scaled quail experience during winter.

Scaled quail managers should also consider local hydrology when conserving and enhancing habitat in arid landscapes. Using hydrology as a management tool, conservation efforts can be refined and directed to landscape features that will maximize the output of applied strategies by increasing available moisture. This can boost the potential of these efforts to provide habitats that support scaled quail through this challenging time of year.

Photos courtesy of TEXAS A&M AGRILIFE EXTENSION SERVICE

Time and time again, landowners construct a new pond and as soon as it begins to fill, they contact our offices and ask what aquatic vegetation they should plant to support their fish.

We provide them with a simple answer—none.

Don’t worry, aquatic vegetation will come on its own eventually, whether you want it or not. It may be one year or five years, but it will eventually be introduced and established. We suggest you enjoy those first few years of a weed-free pond while you can.

Approximately three years following pond construction, more than 90% of

these inquiries are landowners seeking control methods because aquatic vegetation has overgrown and become a nuisance. Most often this leaves pond owners with the task of long-term management that can often be quite expensive.

Think of our popular warm-water fish species commonly stocked into farm ponds, such as largemouth bass, bluegill, redear sunfish, channel or blue catfish, hybrid striped bass, or fathead minnows. Do they really need aquatic vegetation for any reason? Do any of these fish eat aquatic vegetation?

No. If they did, we would not need to import non-native species such as grass carp from Asia or tilapia from Africa to manage aquatic vegetation. Rooted or vascular aquatic vegetation only dies back annually during the fall and has thick cell walls that break down very slowly through bacterial decomposition.

For these reasons, it is not a great source of detritus to feed detritivores in your pond, compared to phytoplankton, the microscopic, single-celled algae that gives pond water a light green tint. There may be up to 10,000 + phytoplankton cells per milliliter of water, living an average of 14 days, producing a constant rain of detritus, unlike rooted or vascular vegetation, being produced for food.

Some inaccurately believe rooted or vascular vegetation is needed for oxygen production. This is not true and most rooted or vascular vegetation species are net oxygen consumers—consum-

ing more oxygen underwater than they produce. They do produce oxygen during daylight hours, but they are still living tissue and must respire or consume oxygen to live during periods of darkness. There can be 8-14 tons of rooted vegetation per acre, and all that living tissue consumes large quantities of oxygen at night.

For this reason, low dissolved-oxygen fish kills caused by excessive aquatic vegetation is the number one cause of fish kills in farm ponds in Texas, occurring at night or just before dawn. Conversely, phytoplankton produces up to 80% of a pond’s usable excess oxygen with the remainder coming from the atmosphere through diffusion and agitation from wind and wave action.

Some may argue that fish need rooted vegetation for habitat or cover, which is not correct. Yes, there are thousands of oxbow, playa, resacas, and coastal marsh “lakes” in Texas. Playa lakes go dry most years and don’t have fish. Oxbows are frequently muddy like the rivers they were formed from and tend to have little vegetation. And resacas, which are not full oxbows, are still connected to the rivers from which they formed and are again often muddy with little vegetation. Coastal marsh lakes

are not freshwater systems where we find fish species common in ponds.

In short, most of our “natural lakes” in Texas are muddy, turbid, and have little aquatic vegetation, yet the fish species we stock in our ponds have been here for millennia. Where did these fish species evolve? Primarily in our rivers and streams that tend to be turbid and muddy with little aquatic vegetation.

So, if pond fish species evolved in systems in Texas without significant aquatic vegetation, what do they use as habitat? Small fish use shallow water as habitat to avoid predation by larger fish. How do fish avoid aerial or overhead predators? They move deeper. Depth changes and bank contours serve as the primary habitat used by our common pond fish species.

There are urban centers in Texas with thriving fish populations including bluegill, bass, and catfish that are nothing more than concrete bowls formed by storm water ditches, irrigation projects,

and flood relief infrastructure. These habitats have no rooted vegetation at all.

Too much aquatic vegetation can lead to a phenomenon called prey avoidance, in which large predatory fish, such as largemouth bass, cannot obtain sufficient food because their prey are hidden in thick aquatic vegetation where they cannot successfully maneuver and hunt. This can lead to poor growth, reduced fishing quality, and eventually stunting as predatory fish cannot satisfy energy growth requirements.

While there is a time and place for aquatic vegetation, for instance shoreline plants for nutrient uptake, erosion control and other specific uses, rooted aquatic vegetation is NOT needed to support a successful fishery. If in doubt or worried about fish habitat, there are other alternatives such as adding wood (brush piles, trees), rock (rock piles, boulders, gravel spawning flats), or synthetic structures to your pond that are better habitat and easier to manage than aquatic vegetation.

Article and photos by

DAVE RICHARDS“Hey, I’m going to text you a game camera photo of a buck that I think is Touchdown. If it is, his frame has changed a bit from last year. Look and let me know if you think it’s him,” said Cuatro Hindes. Touchdown would be 7½ and his antlers should be one of the best sets he had ever grown, so I was anxious to see how his antlers had changed.

Observing the image, I immediately noticed this buck’s antler frame was different but shared similarities to the typical goal post shape that had given Touchdown his nickname years ago.

This buck’s upward sweeping beams were not as distinctly U shaped as Touchdown’s had been, but I felt pretty sure it was him. If so, he had a larger frame than the previous year, and he also had a nice drop tine which he had never grown. The nighttime game camera image wasn’t clear enough to see the white diamond-shaped patterns around his eyes and the distinct white markings just above his nose which had also been some of his identifiable traits.

So, I looked at my previous year’s photo files of him, scanning for comparisons. Cuatro had also mentioned seeing a thin,

1-inch tear in Touchdown’s right ear in a photo from the previous year. Looking at my photos, I noticed a tear showed up on the previous two year’s photos of him. I had my identifiable mark. I just needed to verify if this buck also had the tear.

Before the hunters arrived that season, I set up where the buck had been feeding and captured some new images of him. I immediately viewed the image of the buck’s ear on the back screen of my camera and could see the tear. The buck was Touchdown. I couldn’t have been happier when an old friend’s son had the privilege to hunt and harvest Touchdown later that season.

Every season, Cuatro, John, Little Roy, my sons and I discuss multiple bucks on the Hindes Ranch. Having several sets of trained eyes on the property identifying individual bucks is extremely helpful. Having quality photos of those bucks over consecutive years gives us the assurance that we are all talking about the same deer, enables even more critical observation for identifiable markings and aging, and provides a level of confidence when harvest decisions are made.

While increasing in frame size, mass, and sometimes the number of points each year, most mature buck’s antlers will maintain the same overall shape until the buck passes his prime. However, occasionally a mature buck’s antlers will change for a variety of reasons as Touchdown demonstrated that year. So, it

always helps to use multiple identifying marks for reference to be 100% certain of their identity.

Identifying bucks as young as possible is critical to the success of a whitetail management program. If a buck is already 5½ or older the first time he’s observed, it is difficult to determine his exact age. So, identifying as many young bucks at 1½ and 2½, when aging them is simpler and invaluable.

Simply knowing each buck provides them an opportunity to live to 6½ to 8½ when their antlers typically reach their full potential. That’s why Big Roy Hindes asked me to photograph every deer I saw and especially the young ones when I first started photographing on the Hindes Ranch in the early 1990s. He knew the value of identifying those young bucks so he and Little Roy could manage their deer herd by individual age and always have some of their best bucks around to reach their full antler potential each and every deer season.

Identifying individual whitetail bucks is not nearly as difficult as you may think. It simply requires learning what to look for. Whitetail bucks are just as unique in appearance as humans, and it is no more difficult than identifying human friends and acquaintances. It’s just that most people lack the opportunity or desire to spend the amount of time observing deer to recognize the wide variety of differences in their appearance.

The key to identifying individual bucks is picking out identifiable characteristics and markings that are distinctive to them. Their antler shape, size, and color can all be good references after a buck is 3½ or older. However, the shape, color, and uniqueness of markings on their face and body are more reliable.

This is especially true when identifying young bucks, as their antlers can change significantly those first few years. These identity markings will also prove valuable when identifying the same buck over its lifetime.

Some markings are very obvious, while others are very subtle and take a discerning eye to notice. Look at their ears, eyes, and around their nose and mouth, noting the unique pattern of the black and white markings or even the lack of them. Bucks’ ears can also have tears, essentially torn spots they will exhibit for the rest of their life.

Notice the position of their ears as some may have more erect ears while some lay flat. Some have short, rounded ears and others have long, pointed ears. Notice the amount of white under their chins and how far it appears up their faces and down their necks. Do they have a white throat patch under their chin and what is its shape, size, and is it bold or faded?

Some bucks will have more black markings on their faces, while others will have more white markings on their faces, necks, and legs from their knees to their hooves. Bucks’ tails can be extremely unique in their color patterns, making certain bucks immediately identifiable. Some bucks have lost some or all of their tail and it will never grow back.

Bucks’ eyes can appear coal black to clear amber. Some bucks appear to be squinting while others are bug-eyed. Their forehead gland, or patch of hair between their antlers, can appear dark brown, reddish, or sometimes grey and can add another clue to their identity.

When observing the various color markings with the aging characteristics of the buck’s body and head, you can clearly see how each buck can be identified among its peers.

Understanding all the visual cues to identify an individual whitetail buck makes recognizing them easier, but having a photograph that records that buck and its identifying markings is an extremely beneficial management tool. This is especially true if the location and date are added and it is filed by blind location or pasture name where it can be easily located and quickly retrieved.

In just a few years, you will have a reference log that identifies numerous bucks and gives the landowner or manager more confidence in their harvest decisions each season. This information has many valuable benefits. For instance, the landowner/manager/hunter may also learn about a known buck’s movements as it is observed in other locations on the property at certain times each hunting season.

Identifying individual bucks is a learned skill and a key component for them living and reaching their full antler potential. “Observing & Evaluating Whitetails” is a book that has much more on this subject, including more than 425 color whitetail images that illustrate many of the identifying markings mentioned and just how uniquely different hundreds of whitetail bucks can be. It can be purchased through the Texas Wildlife Association.

PRE-REGISTRATION FOR TICKETS CLOSES JULY 8th

• ONLINE REGISTRATION

Register online at https://www.texas-wildlife.org/wildlife-convention/

• AUCTION BIDDING REGISTRATION

Register online at https://www.onlinehuntingauctions.com/Texas-WildlifeAssociation_ae2929

• FOR HOTEL RESERVATIONS

Register online at https://www.texas-wildlife.org/wildlife-convention/ Group Rate is $240/night Standard Room plus state taxes, local taxes, resort fees and parking. Reservations must be received prior to June 19, 2024.

When most humans hear the term “predator,” they probably think of 80s action movies with bodybuilding heroes or large, dangerous carnivores—proven maneaters like lions, grizzly bears, and great white sharks. Some of the world’s most efficient predators, however, fly under the radar as they wrack up body counts in the thousands. I’m talking specifically about wood warblers of the family Parulidae.

Parulidae is a family of New World songbirds that contains some of the country’s most beautiful bird species. They rank among the most prized targets for bird watchers and nature

photographers and are renowned for their incredible colors and impressive diversity. They are also deadly—if you’re a bug, that is.

I once watched a Northern parula (Setophaga americana), a beautiful canopy dweller adorned in yellow and metallic blue, capture four caterpillars, two spiders, a moth, and about a dozen aphids in less than 20 minutes. Extrapolate that voracity to an all-day every day eating spree and it’s easy to see why these tiny birds instill fear in invertebrate world—if in fact such creatures can feel fear.

And the birds are tiny. A Northern parula is about 4.5 inches long, has a wingspan of 7 inches or so, and weighs less than onefiftieth of a pound. They spend their winters in Central America

and the Caribbean and migrate to the eastern U.S. and southern Canada in the summer to breed. This breeding range includes roughly the eastern third of Texas, where they are a familiar resident of mature, hardwood-dominated forests.

Though they may be familiar, they are seldom seen. They are, however, often heard. Their loud, ascending trill carries through the summer woods. Warblers are just as famous for their beautiful songs as they are for their bright plumage.

In fact, the word “warble” means to sing a complicated song, and this group of birds certainly lives up to that moniker. In Texas, warblers may occasionally sing as they migrate through the state. The real show, however, is put on by the birds that stick around to breed, as males diligently belt out tune after tune to defend their territories and attract a mate.

Many birders focus on finding warblers during migration, and travel by the thousands to coastal woodlots like those on High Island in hopes of experiencing a “fallout,” when harsh weather over the Gulf of Mexico might cause millions of birds to descend to the trees, starving and desperate for rest.

If they’re really lucky, a birder might spot 25 to 30 species of warbler in a single day. I prefer to seek them out once they’ve settled into their summer residences, and when it comes to summer warbler diversity in Texas, the Piney Woods can’t be beat. Of the 20 or so species of warblers known to nest in Texas, 13 of them nest behind the Pine Curtain.

Warblers in the Piney Woods can be found in a variety of habitats. Some are plastic in their habitat preference, meaning they can thrive in a variety of areas, while others are specific, requiring just the right conditions.

Take the Louisiana waterthrush (Parkesia motacilla), for example. Adorned with a brown back and a whitish breast with numerous brown streaks, this little warbler makes its home along shallow creeks flowing through high-quality, mature forests. They can be identified by their bold, white supercilium—a narrow line that runs from the base of their beak, above the eye, to the back of the neck.

The Louisiana waterthrush can also be identified by its behavior. It tends to bob its body up and down as it bounces along creek banks and low branches overhanging the water. The waterthrush builds a small cup nest right on the creek bank, often among exposed root balls or logs and branches washed downstream by flood events.

Perhaps the most striking of all Texas warblers is the Prothonotary warbler (Protonotaria citrea). Named for the colorful robes worn by court officials of the Byzantine empire, these birds are almost impossibly yellow. They are so bright that they’ve earned the nicknames “swamp torch” or “swamp candle,” a reference to their brilliant plumage and the generally dark places they inhabit.

Prothonotary warblers live in bottomlands, swamps, and riparian gallery forests where they sing a loud song that some

have described as sounding like “SWEET SWEET SWEET SWEET.” They are one of only two cavity nesting warblers in the country.

Another sought-after warbler of East Texas is the hooded warbler (Setophaga citrina). This species is named for the black “hood” of males that contrasts sharply with its bright yellow face and belly and olive wings and back. Hooded warblers like to hang out in dense understory shrubs and cane thickets within mature pine-hardwood forests. The outer tail feathers of these warblers are whitish, and it is believed that by flashing them they startle insects from hiding places.

Other warblers of the understory include the Kentucky warbler (Geothlypis formosa), the black-and-white warbler (Mniotilta varia), Swainson’s warbler (Limnothlypis swainsonii), and the worm-eating warbler (Helmitheros vermivora). Kentucky warblers look somewhat similar to hooded warblers, but instead of a hood they have a black mask and cap and pinkish legs. Kentucky warblers are especially furtive and like to skulk in dense underbrush away from prying eyes.

Black-and-white warblers are aptly named for the alternating white and black bars in their plumage. Their song has been likened to a squeaky bicycle wheel, and they can often be seen moving up and down the trunk of trees like creepers and nuthatches.

Swainson’s warblers are infamous for being difficult to ob-

a buffy supercilium. Their bills are heavier than most warblers and their legs are pinkish.

Worm-eating warblers are uncommon in the Piney Woods, but they have been recorded nesting in the region, and I have encountered individuals that I believed to be on territory in Newton County.

Some warblers spend their time high in the treetops. Species like the Northern parula, yellow-throated warbler (Setophaga dominica), and pine warbler (Setophaga pinus) primarily forage in the canopy, though occasionally they might drop down to the understory or even the forest floor when the getting is good.

Yellow-throated warblers are especially striking. Adorned primarily in gray, black, and white, they have a bit of flare in the form of a bright yellow throat. Pine warblers are a dull yellow with white wing bars and faint streaking in the breast. Though they have a penchant for pine forests, they may also be found in areas where mature hardwoods are present.

While most warblers are found deep in the woods, others can be found in treeless areas. Common yellowthroats (Geothlypis trichas) inhabit marshy or shrubby wetlands with ample cover. During the spring and summer, their song “wichity wichity wichity” is a familiar sound. Prairie warblers (Setophaga discolor) don’t live in prairies, but prefer areas in the early stages of succession, where dense shrubs and young trees provide cover.

There are other warblers that breed in the Piney Woods. American redstarts (Setophaga ruticilla) have been documented

nesting here, though observations of nesting individuals are infrequent. Cerulean warblers (Setophaga cerulea), a fan favorite of bird watchers, once nested in riparian hardwoods in far northeast Texas, though they have not been documented here in recent times.

A wonderful world of warblers awaits those willing to brave the heat, humidity, biting insects, and toxic plants of the Piney Woods in summer. These minor inconveniences should not deter you from seeking them out, however, and there are plenty of places to spot them along woods roads and maintained trails.

The national forests are a good place to start, and most species can be found there. There are also several state parks in the Piney Woods with well-developed trail systems where you can stretch your legs and listen for their sweet songs.

So grab your binoculars and camera and head east to discover the warblers and other natural wonders waiting among the trees.

The Lone Star State’s rainbow trout fishery provides unique wintertime opportunities for anglers. These fish are stocked in a variety of locales across the state and have become popular among the freshwater angling crowd. From conventional, light spinning tackle to fly fishing gear, anglers of all experience levels can enjoy the pursuit of Texas ‘bows using a variety of tactics.

According to TPWD Freshwater Hatchery Program Director Carl Kittel, approximately 350,000 rainbow trout are stocked annually between the week of Thanksgiving and the first week of March. These stockings take place across about 210 stocking sites.

“TPWD purchases the trout from an outside supplier, with the goal of having enough fish to meet all of the planned stockings and requests for stockings at certain locations,” Kittel said. “Typically, we end up having a surplus of trout, and we work with our biologists to find additional sites that would be useful for anglers each year. The number of stockings or stocking sites are almost always on the rise.”

TPWD has two different programs that stock rainbow trout at various sites across the Lone Star State. They include the standard TPWD Trout Program and the Neighborhood Fishin’ Program.

According to Kittel, the Neighborhood Fishin’ Program oversees 18 stocking sites where TPWD partners with larger cities and urban areas to stock rainbow trout in community lakes about eight times throughout the winter months.

“Our regular stockings from our TPWD Trout Program consist of rainbow trout that are 8–10 inches in length,” Kittel said. “There can be some variations within this size range, as it is not an exact science. Sometimes the trout are on the smaller end of that range, and sometimes they are on the larger end. For the most part though, most fall within 8–10 inches in size.”

Rainbow trout stocked in community lakes under the Neighborhood Fishin’ Program are typically a little larger, ranging from 10–12 inches long. This is by design, as the program also stocks channel catfish that are about 12 inches in length as well. That way, there is consistency among the fish that are available for anglers at Neighborhood Fishin’ Program stocking sites.

“Just about all of the trout stocked by TPWD are about 8–14 months old,” Kittel said.

Kittel said that all stockings conducted by TPWD within the Trout Program and the Neighborhood Fishin’ Program are part of a cooperative effort between TPWD and numerous municipalities, county recreation departments, organizations, and other partners.

“We have upwards of 99 partners that help us with our rainbow trout stocking efforts,” Kittel said. “These collaborative efforts allow us to provide anglers with quality winter fishing opportunities each year.”

Kittel said the majority of TPWD rainbow trout stockings are intentionally conducted with a put-and-take mindset.

“Most of these fish are being stocked in areas with the intention of being easily available for anglers to catch,” Kittel said. “We are trying to promote angling opportunities in urban settings, with hopes of recruiting more folks into the angling community. Perhaps this will motivate more people to take advantage of angling opportunities along some of our state’s larger reservoirs and rivers.”

TPWD inland fisheries district biologists make requests and recommendations as to where certain trout stockings should take place, and how many fish should be included,

based on certain ecological and biological characteristics for a specific fishery or water body. These stocking requests and recommendations are made with the intention of being useful to the fishery and anglers.

“All of our stockings are calculated,” Kittel said. “We don’t want to stock fish in areas where anglers are not interested in fishing, or in places where it will not make sense environmentally.

“Even when our partners make requests for stockings, these requests are overseen by the district biologist for whatever fishery or body of water the request is being made for. It’s all about science and angler opportunity.”

The Canyon tailrace, which consists of the first 4 miles or so of the Guadalupe River below Canyon Lake Reservoir near New Braunfels, is the only body of water in Texas that can support stocked rainbow trout year-round. The tailrace receives approximately 20,000 rainbow trout from TPWD stockings each year, as well as additional stockings from private entities and organizations such as Trout Unlimited.

According to the San Marcos-Austin District Supervisor for TPWD’s Inland Fisheries Division, Patrick Ireland, the stretch of the Guadalupe River that is located immediately below Canyon Lake receives continuous cold-water discharges from the reservoir, which makes it the perfect haven for rainbow trout. Ireland said the tailrace consistency holds water temperatures that are cool enough for rainbow trout to survive Texas summers, and it offers a variety of invertebrates and other foraging opportunities for the fish.

“Invertebrate studies have been conducted along the waters of the tailrace over the years,” Ireland said. “These studies have shown that there are plenty of invertebrate food sources available to sustain a thriving population of trout throughout the year.”

In addition to invertebrates, Ireland said that rainbow trout will also eat small fish.

“We are seeing a lot of rainbow trout living within the Canyon tailrace survive year after year,” Ireland said. “Anglers practicing catch-and-release and proper handling of these fish have really

A schedule of trout stocking dates and locations can be found at the TPWD website: https://tpwd.texas.gov/fishboat/ fish/management/stocking/trout_stocking.phtml

Some stocking sites receive multiple stockings throughout the trout season. Harvest regulations and license requirements can be found at this webpage as well.

helped the tailrace begin to earn a reputation as a reputable, trophy rainbow trout fishery.”

Ireland said that anglers who are willing to minimize how much they handle these fish will help ensure that a caught and released rainbow trout will have the chance to continue to survive and grow, and be caught again by another angler.

“We like to encourage anglers to use a net when landing trout and to keep them in the water as much as they can,” Ireland said.

According to Ireland, the Canyon tailrace is known for producing good numbers of trout over 18 inches, and that fish reaching 24–25 inches in length or more are fairly common.

Perhaps the largest threat to rainbow trout inhabiting the Canyon tailrace is a major flood event. Ireland said that if a massive flow of floodwater pushed or flushed the trout further down the Guadalupe River where water temperatures are warmer, a decline in the population of holdover fish, or those that have been surviving for multiple years along the tailrace after their initial stocking, would happen.

The current water level of Canyon Lake is at an all-time low, so flooding is unlikely. It would take a flood of historic proportions for trout inhabiting the tailrace to be affected.

Ireland said there haven’t been any environmental factors or events in recent years that have posed a threat to the Canyon tailrace’s rainbow trout. Therefore, anglers can expect to encounter trout of all sizes during the winter months, from smaller ones that have just been stocked, to larger fish that have carried over from one year to the next.

“The Canyon tailrace is considered the southernmost trout fishery in the United States,” Ireland said. “With its unique location between the two rapidly growing cities of San Anto-

nio and Austin, the fishery provides a one-of-a-kind opportunity for trout anglers of all levels of experiences, right here in Texas.”

Because they are a cold-water species, rainbow trout begin to become stressed once water temperatures start to rise above the 70-degree mark.

“The water temperature threshold to support rainbow trout is 72 degrees Fahrenheit,” Kittel said. “If the water temperature remains at 72 degrees for a week, the fish will become very stressed. If it were to stay that high for a month, the fish would certainly become sick. Once the water temperature rises to about 75- or 76-degrees Fahrenheit, rainbow trout can only survive for up to a few hours and as little as a few minutes.”

A map indicating special harvest regulation zones can be found at: https://tpwd.texas.gov/fishboat/fish/management/ stocking/guadalupe.phtml#:~:text=Trout%2012%20 inches%20and%20under,a%20one%20trout%20daily%20bag

This webpage also highlights public access locations along the Guadalupe River for trout anglers.

When water temperatures are below 70 degrees, Kittel said rainbow trout can survive and thrive.

“The fish don’t care how cold it gets,” Kittel said. “As long as the water remains liquid, they are happy.”

According to Kittel, the species’ intolerance of water temperatures above 72 degrees Fahrenheit is genetically predetermined.

“The water temperature threshold is based on the enzymes that drive the physiological functions of rainbow trout,” Kittel said. “The actual molecules, such as long chain proteins that are involved in digestion, respiration, and energy production within rainbow trout, begin to break down at warmer water temperatures.”

Kittel said this is why TPWD cannot successfully grow trout under its freshwater hatchery programs in Texas, because the water temperature at hatchery locations does not stay cool enough during the summer months. The trout are purchased from an out-of-state supplier and then delivered to Texas hatcheries during the fall and winter when water temperatures are cooler, before being distributed to stocking sites.

Kittel said that a significant amount of funding for TPWD’s trout program comes from grants made available to the state from the Sport Fish Restoration Program by the Sport Fish Restoration Act, administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

“Grants from the Sport Fish Restoration Program are supported by taxes on fishing equipment, electric motors, sonar, and motorboat fuel,” Kittel said. “These grants pay us $3 matched for every $1 of license sales.”

“Together, all of these grant funds, entities, and populations of people, are what make our state’s rainbow trout fishery a huge success,” Kittel said.

The Lone Star State’s winter rainbow trout fishery is definitely a success story, and it’s something that many anglers are taking advantage of. Through collaborative and collective efforts from TPWD, its partners, and Texan trout anglers, rainbow trout angling opportunities will surely be enjoyed by many generations to come.

Used by wildlife biologists, educators and managers throughout the country, Observing & Evaluating Whitetails is a must-have resource for anyone interested in learning more about North America’s most popular big game animal!

This isn’t a reprint but an updated edition with NEW aging and judging sequences of unique bucks!

• Over 470 color photographs

• 21 buck aging sequences showing their body and antler changes over their life

• 35 judging examples of live bucks with known Boone & Crockett scores

• Why we don’t use antler size as an aging criterion

• Estimating Boone & Crockett score on the hoof

• Whitetail communication and sensory capabilities

• Whitetail antler development and anomalies and much more!

OBSERVING & EVALUATING WHITETAILS

UPDATED EDITION by Dave Richards & Al Brothers

$35 each includes shipping

ALSO AVAILABLE:

AGING WHITETAIL BUCKS ON THE HOOF

By Dave Richards & Al BrothersA pocket companion to Observing & Evaluating Whitetails

$10 each includes shipping

does present some challenges. Similar to domestic goat or sheep, slow braises, curries, and stews are the perfect solution.

I went into the field as I typically do—with low expectations of seeing an aoudad let alone harvesting one—but I went with a positive spirit to experience the natural world around me. I knew Jim Wentrcek was good, but when he spotted a group of aoudad, referred to as an anger, from nearly a mile away, I was impressed. Having a guide like Wentrcek to trust completely was one of the biggest highlights of this experience. Together, the pursuit was on.

“Jim, I see one,” I whispered. Wentrcek whipped around and immediately had his range finder on the adjacent hillside.

“Sure enough, 250 yards,” he replied.

Like a dance, we dropped low to the ground in unison. Propping my rifle on its bipod, I immediately ditched kneeling for prone position atop my backpack. Wentrcek helped me settle in, encouraging me to take my time. I looked down my scope to the appropriate hold over marks. A few deep breaths later and she was down.

Aoudad hunting for the first time was everything I thought it would be and more. Just north of Del Rio where the Edwards Plateau, Chihuahuan Desert and Rio Grande Plain brushland intersect, the terrain was rough and rugged. Steep limestone cliffs gave way to large boulders, dried river rocks, scrub juniper and sharp vegetation at every turn.

The aoudad or Barbary sheep is native to North Africa. However, like many African exotic species, it has flourished in the arid and semi-arid rugged environments of Texas. First brought here in the 1950s, the aoudad continues to earn recognition as a sought-after species to hunt.

With that, however, has come some quandary regarding its edibility. As an exotic species, retaining the meat is not required by the state and I suspect many an aoudad have been left to the vultures. Like most game not highly sought after as table fare, aoudad have been on my bucket list to cook for quite some time.

Certainly, as an animal as tough as its surroundings, cooking aoudad does present some challenges. Similar to domestic goat or sheep, slow braises, curries, and stews are the perfect solution. Looking to the historical roots of the aoudad is a perfect place to start.

This recipe is inspired by my friend and amazing chef, Jeremy Baker, who first introduced me to spicy braises and herbaceous stews. Not only did Baker encourage me to pursue aoudad but he expertly counseled me in developing this recipe. In turn, Baker hopes to pursue aoudad for the first time in the near future and I have pledged to help him get there.

Traditionally made in a conical earthenware pot called a tagine, North Africans use this timeless portable oven to slow cook their meals while moving from one place to

another. Similar to a Dutch oven, this method keeps food moist and infused with spices while simmering.

Ingredients

6 cups diced aoudad

1 white onion, diced

6 cloves garlic, minced

1 tablespoon ginger, fresh grated

1 tablespoon cumin

1 tablespoon ground coriander

1 tablespoon paprika

¼ teaspoon ground cinnamon

1 cup harissa (a spiced chile pepper paste)

2 tablespoons tomato puree

2 ½ cups chopped tomatoes

3 cups beef broth

1 cup dried apricots, chopped

½ cup dried dates, chopped

1 tablespoon honey

1 can chickpeas, drained

Lemon juice

Sea salt and pepper

Greek yogurt

Pomegranate seeds

$39,150,000 | Albany, TX | 9,400± acres

9,400± deeded acres located near Albany, Texas. Beautiful improvements with cooperative water. Located on Highway 351 near Dallas/ Fort Worth, Midland, and Lubbock. Multiple Income and recreational opportunities.

Chopped mint

Extra virgin olive oil

METHOD

1. Marinate diced meat with olive oil, harissa and spices, preferably overnight.

2. In a Dutch oven or cast-iron skillet, brown the aoudad in olive oil on all sides. Remove.

3. Add chopped onion, garlic and ginger to the pan or skillet. Sauté.

4. Place the aoudad, onions, garlic and spices in the slow cooker. Pour in the beef stock and chopped tomatoes. Cook on low for 4-8 hours, or until tender.

5. Add honey, chopped apricots, dates and chickpeas. Cook for another 2030 minutes in the slow cooker.

6. Add lemon juice, salt and pepper to taste.

7. Divide into bowls or serve over basmati rice with Greek yogurt, mint and pomegranate seeds.

$3,250,000 | Centerville, TX | 58± acres

Horse ranch in a picturesque setting with beautiful barns, walkers, and arenas. Strategically laid out with all amenities on 58± acres with homes and trees throughout. Near Houston and Dallas/Fort Worth.

MAKE A DIFFERENCE

This drawing will be open to all who Join or Renew at the Associate Level or higher. The package will consist of the new All Seasons Feeders Corn Pro (feeds both corn and protein), a Mossberg Patriot .270 Win 22” Rifle (donated by Larry Weishuhn), and a Yeti 35 Qt Tundra. The winner will be drawn at the TWA Convention on Saturday, July 13, 2024.

Winner must be 21 yrs or older and need not be present to win. Drawing: 03/15/24 to 07/13/24 10pm cst.

Keep your information secure by scanning the QR code to enter your membership info and credit card payment or go to texas-wildlife.org and click the Join/Renew button.

In May 2022, I wrote about my first road trip to West Texas, and what a wonderful experience it was. There is something about this remote, far-flung portion of the state, with its vast vistas, spellbinding colors, and layers of history embedded in ancient rock, that brings visitors to their knees.

On that visit, I stopped in Marfa, Alpine, and Marathon on route to the 800,000-acre expanse that is Big Bend National Park. The alien nature of this place is truly something to behold, as are its starry skies and endless panorama of the raw, rugged desert. I don’t think any picture or preamble could have

prepared me for the way it would make me feel.

Today I can still remember marveling at the views of Persimmon Gap, with its 500-million-year-old rocks and walking between the 1,500-foot walls that frame Santa Elena Canyon. Later, I watched as windswept clouds cast giant shadows on the weathered terrain, and felt antiquity and modernity converge within the Fossil Discovery Exhibit.

This off-the-grid, open-air structure, designed by the award-winning architecture firm, Lake|Flato, blends into the rustic landscape with its shell of perforated metal. Inside, visitors can learn all about the dino-

saur fossils discovered here while pondering the 130 million years of geologic time represented within this treasured national park.

In a few weeks, I’m traveling back to Marathon once again for a family member’s wedding. Already, I can imagine the striking silhouette of this wild landscape, with its ocotillos and windswept canyons, blooming cacti, and rolling tumbleweeds. Ahead of my trip, I’m revisiting a superlative resource on Big Bend published by Wildsam.

For those unfamiliar, Wildsam is a fun, Texas-based travel brand and media company known for its story-driven field guides to places across America. While the books are pocket-size at just 4 by 6.5 inches, they pack a hefty punch in an inviting, easily digestible format. Find them online at www.wildsam.com.

As with the brand’s other guides, “Wildsam Big Bend” includes places of interest, along with essays, itineraries, park traditions, and trail recommendations, not to mention information on fossils, military history, Chihuahuan Desert flora, and life along the U.S.-Mexico border. One of the best parts about these guidebooks is the compilation of voices that makes each one so unique. In this volume, expect to find wisdom from native plant experts such as Jim Martinez, silversmiths such as Paul Wiggins, and astronomers such as Steven Janowiecki, to name a few.

Lady Bird Johnson is another notable Texan quoted in its pages. In 1966, while hiking the Lost Mine Trail, she was said to have paused on a ridge between Juniper Canyon and Green Gulch in the Chisos Basin before remarking, “This looks like the very edge of the world.”

Now, nearly 60 years later, Far West Texas still feels like the very edge of the world, and I couldn’t be more excited to return now in this last full month of spring.