PORTSMOUTH POINT

RE-

Editorial Team (Magazine and Blog)

Nia Agbaje-Johnson * Lucy Aldridge * Megan Ampim * Diarmuid Bailey * Henry Ball * Sawsene Belaiche * Thomas Biddle * Alec Bradpiece

Annika Bright * Archie Brown * Wilf Brown * Matthew Chedgey * Maya Choudhury * Alice Clarke * Flixy Coote * Nora Copeland * Ben Courdavault

James Curwood * George Cuthbert * Attish Das * Alexandra Dempster * Ashnah Elanchcheliyan * Lily Eldrid * Isobel Firth * Isabel Fisher

Juliette Franks * Grace Gamblin * Ruthie Gawley * Abriti Ghimire * Honor Gillies * Mackenzie Gilmore * Nathaniel Gingell * Jude Gunner

Elliot Hartridge * Sophie Haworth * Jamie Head * Jiali Hicks * Jack Holt * Siha Hoque * Lissiana Jakaj * Kavin Kajendran * Navi Kamalendrarajah

Sam Kalra * Evie Kell * Thomas Kroll * Fraser Langley * Sam Lewis * Anna Medina * Oscar Mellers * Natalie Moras * James Mullen * Sidra Nouyan

Tishe Osunlana * Isobella Palmer-Ward * Nikhil Patel * Iona Perkins * Marinela Pervataj * Amelia Rahman * Rowan Reddy * Tabitha Richardson * Sabiha Sabikunnaher * Dawn Sands * Steven

This is the first issue of Portsmouth Point to be predicated on a prefix.

Re- suggests that cyclicality lies at the heart of existence. From earliest history – whether through the Egyptian symbol, Ouroboros, the Hindu belief in reincarnation or the Christian faith in resurrection – human beings have sensed that the physical death of each individual is not a metaphysical reality. Even in our more secular era, the language of rebirth and redemption pervades our culture, from Beckham to Beyoncé

However, although humans seem designed to seek meaning, we live in a universe which often seems to evade it. This is the condition that Albert Camus labelled ‘the Absurd’ in his philosophical essay, ‘The Myth of Sisyphus.’ It is through myth, art and literature that we have sought to create meaning for thousands of years, in a continuous cycle of intertextual interpretation and reinterpretation: from Virgilian epic to mediaeval romance, Shakespearean tragedy to dystopian novel.

Writer Walter Benjamin personified History as a winged angel, its face permanently turned toward the past as its wings propel it irresistibly into the future, blown by the storm of progress. It is said that those who fail to learn from history are condemned to repeat its mistakes. However, ‘black swan’ events suggest that, in a world of increasing complexity, much remains unpredictable and perhaps unrepeatable. Indeed, the modern era has been characterised by revolution: religious, political and technological.

In the wake of the disruption that revolution brings, how do we find justice? Do we choose the path of revenge or of reconciliation? One of the greatest disruptions we face right now is climate change. This has led to an increasing focus on regeneration, rather than revolution, with reforesting and rewilding that benefit from the latest biotechnology but also return to traditional methods of conservation dating back centuries.

And for many centuries, religions and cultures have celebrated festivals at this time of year - the Winter Solstice – to mark the return of the Light, as days slowly begin to lengthen for the first time since midsummer. It is a period in which we look to the future and reflect on the past. This Re- issue of Portsmouth Point offers much to reflect on during this cyclical season, and the editors wish all of our readers a recreational and revivifying break.

The Editors

December, 2023

OUROBOROS

ETERNAL SYMBOL OF CYCLICALITY

Lily Eldrid YEAR 12Asymbol of rebirth, regeneration and renewal, the ouroboros is one of the most highly recognised symbols, adapted throughout time by many cultures and belief systems. It might seem odd, on first reflection, to connect a snake eating itself to the human experience, but human art and religion has been drawn to this symbolism again and again. The ouroboros holds many meanings, the interpretations varying from spiritual to metaphorical, from monster to god.

The oldest known use of the symbol dates to the Ancient Egyptians, specifically the tomb of Tutankhamun, showing its prominence in their society to be deemed important enough to feature in such an influential figure’s burial site. There is a myth that goes along with the symbol’s meaning; Ancient Egyptians believed that the god, Ra, who would be born again each morning, would travel across the sky in a boat and, as the sun set, he would die and join Osiris in the underworld. He was challenged by the god of chaos, Apep, who would create storms and thunder to try and stop his journey, but thankfully Ra was accompanied by “the enveloper” Mehen. This snake protected Ra through his journey across the sky and into the underworld each day. This natural aetiological myth explains the rising and setting of the sun, weather and the way in which Ancient Egyptians would measure time. Instead of time being something linear, the Ancient Egyptians believed that it was instead something cyclical and the ouroboros was the perfect symbol of that renewal and repetition that they believed every day brought with it. As the

myth also implies, the ouroboros could be seen as a guardian or protector, like Mehen to Ra, and this would make its appearance in Tutankhamun’s tomb understandable, relying on the symbol for safety in his trip to the underworld.

'ONE IS ALL AND THROUGH IT IS ALL, AND BY IT IS ALL, AND IF YOU HAVE NOT ALL, ALL IS NOTHING.' (From ‘Chrysopoeia Of Cleopatra’ , 1st Century CE).

The Greeks first gave the ouroboros its name, translatable as ‘tail-devourer’. The Greek school of thought, Hermeticism, thinks of it as a symbol of death and rebirth, the snake’s head destroying and consuming itself and the tail regrowing, in an endless cycle. The philosophers of Ancient Greece approached it from different angles, however. For Plato it meant self-reliance, the snake being all it needed to keep living, the joined nature of the tail and the head meaning it was alone in itself. He also talked of the more sinister side to the symbol - self destruction - and the potential it had to consume itself whole. Plato related the snake to the human condition, and so did the dramatist, Sophocles, when he suggested that the symbol was the opposite to human experience; unlike the ouroboros, we can stray from the circular path that is its life and instead explore different directions. He sees this as a more dangerous way of being compared to the snake’s fixed nature, as human beings have chances of succeeding and moving forward, but also of failing and falling backwards. The image also correlates with the Greek myth of Sisyphus, in which he must roll a boulder up a hill only for him to let it fall back down again and repeat the process. This continuation and repetition ties into the infinite devouring and renewal of the snake.

The symbol was also adopted by alchemists who, among other metaphysical considerations, sought to transform base metals into gold. In a broader sense, they wanted to push the boundaries of transmutation and take something to make it something else. They saw the ouroboros as a representation of unity of all matter, material and spiritual, that cannot be destroyed but can be changed. This essential insight relating to the conservation of matter in science is taught to this day, furthering how timeless and influential the ouroboros symbol was in shaping and reflecting how we understand the world.

Gnostic philosophers took a completely different approach to deciphering the ouroboros symbol, their belief in the close relationship between themselves and the divine being the fuel for their interpretation. They saw the head of the snake as God and the tail as humans. They believed they would reach this unity with the divine by becoming enlightened to religious truth. The head devouring the tail shows the spiritual world and the physical world in constant battle, but also in peace. This equilibrium is seen as necessary for the unity of the universe. In the sense of the ouroboros symbolising balance, it is often compared to the yin and yang of Chinese philosophy. They both convey the idea that contrary forces can exist together in harmony. Gnosticism became an influential branch of Christianity in the second and third centuries CE, with many Gnostic Christians seeing the ouroboros as God (the head) giving rebirth to humans (the tail) through resurrection.

In the early twentieth century, pioneering psychologist Carl Jung, presented the ouroboros as a symbol for the human psyche.

The ouroboros is a state you need to attain to achieve wholeness, when your unconscious mind and your conscious personality live together. He believed this could be achieved through self-reflection. In the modern era, the symbol has also been reinterpreted to represent infinity, conceptually used to create art like the Droste effect and Mobius strips. In Victorian times, people would wear it as jewellery to signify their mourning for someone who had passed and the eternal love they held for that person. The fact that the ouroboros symbol is still being used in the twenty-first century brings home how fluid its meaning can be, but also how connected the human experience is that we can all in some way relate to it.

In my own interpretation, I see the ouroboros as a symbol of rebirth, but also of self-destruction. There are two parts to the process of the ouroborus’ existence; the continuation of the tail, but also the snake eating itself in the first place. I see it more as a transaction, where one can’t exist without the other. There must be dark to have light, there must be evil to have good, and there must be death to have life. The ouroboros sums up the balance of existence itself, and so it is neither a negative or positive symbol, but, instead, a truthful one. I feel this is why, when used in any interpretation, the ‘tail-devourer’ always seems to fit. This snake has survived generations, and I believe it will survive many more.

Attish Das YEAR 10

A KARMIC JOURNAEY

Forty-six per cent of human beings, in our beloved world, are thought to have faith in an experience of life after death: through their soul, in many forms. This concept has been shaped by ancient religions and faiths - from Hinduism and Buddhism to Christianity - but also, increasingly, through scientific theories and practical investigations. In the modern era, many people have discussed and debated the events that occur subsequent to human demise, with other people and with themselves. However, the truth is not physically explainable to the conscious mind.

Researchers at New York University’s Langone Health Centre have investigated short-term events immediately after the final moments of life. It has been stated that death is when the body’s

BOTH HINDUISM AND BUDDHISM DEFINE 'KARMA' AS THE SUM OF A PERSON'S ACTIONS IN THIS AND PREVIOUS STATES OF EXISTENCE AND AS SHAPING THEIR FATE IN FUTURE EXISTENCES.

heart stops, but not all the cells instantly disappear; instead, they go through a dim, decaying process. A human being will not be able to do anything following the stopping of the heart; however, the entity inside the human being is still conscious for a given amount of time. Recently, doctors in Canada placed an 87-yearold man into a brain-wave scanner, which, unfortunately, induced a fatal heart attack. However, throughout the process, the patient was still being scanned by the machine. When the doctors checked the results, they observed unusual factors; for example, during the thirty seconds before and after his heart stopped, the man’s brain waves increased sharply, something which only happens during occasions like memory recovery, meditation, and lucid dreaming. This has led to the conclusion that the brain has time to perform a final act, which may be a moment where the whole life can be replayed in his imagination one final time.

However, such scientific insights are only tentative at present. For now, religion, faith and philosophy, continue to be the main frameworks for reflecting on life after death. For example, traditional Christian belief suggests that death is not the end, and that God will decide whether a human being will spend eternity in Heaven or in Hell. Heaven is presented as an indescribably exquisite place presided over by God, who wipes away every tear (symbolising that there is no pain, suffering or mourning in heaven); Hell is presented as presided over by Satan, existing as the place for punishment for the unrighteous. While some traditional theologians argue that Hell is literal, many theologians and believers, in the modern era, see Hell as symbolic of the frustration of not being able to be in the presence of God.

The Hindu faith is centred around reincarnation, the belief that, when someone goes through death, the soul of their body is recycled and reborn as a different form. Hindus believe that the soul continues in a cycle, depending on their actions throughout their previous life until it settles upon its true nature, which may take many lifetimes, but the aim is to strive closer to Brahma, the God of creation. This belief had a profound influence on Buddhism. Both Hinduism and Buddhism define ‘karma’ as the sum of a person's actions in this and previous states of existence and as shaping their fate in future existences. The concept of "karmic energy" derives from the idea of karma, which holds that our deeds, intentions, and thoughts produce an energy field that shapes the experiences we have in the future. It is like the law of balance: good deeds generate good energy, and bad deeds

generate bad energy. Throughout multiple lifetimes, this general energy moulds our present and future conditions as well as our spiritual development.

Enlightenment is the primary goal for those who practise Buddhism. Classic, traditional scriptures teach that, for those who are not yet perfect in wisdom and compassion, more lives are available to keep making progress, through rebirth, an equivalent of reincarnation. The transfer of consciousness from different physical beings would last over a period of hours or days, depending on karma and the state of mind when dying, including meditative practice, which brings peacefulness and tranquillity to the mind, increasing the karmic energy obtained.

The subject, as a field of study, is not supported by science. It is considered a belief or a philosophical concept rather than a scientifically proven phenomenon. Science takes a systematic and empirical approach to studying given events and objects, relying on experimentation and reasoning, based on evidence, to explain observable phenomena to the inquiring mind. Philosophy is a broader discipline, which explores fundamental questions about existence and the nature of reality, using critical thinking, logic and abstract concepts, often exploring moral questions. Both fields contribute to our understanding of the world, but they approach immersed knowledge and inquiry from different angles and perspectives. Reincarnation, at present, remains a philosophical, rather than scientific, area of study and debate.

It is worth reflecting on why forty-six per cent of human beings continue to have confidence in some sort of life after death, including reincarnation. There is no clear truth about our individual futures after death, so it is a source of constant speculation, from the Christian view of a soul journeying on after death to the Hindu and Buddhist perspective of reincarnation and rebirth decided upon by the quantity of karmic energy gained throughout an individual’s lifetime. From metaphysics to ethics, from the foundation of the vast universe to the completion of reality, the concept of the journey of a soul through different lifetimes has to be a source of great gratitude.

RESURRECTION

CAN SCIENCE BRING US BACK FROM THE DEAD?

Siha Hoque YEAR 11To resurrect a being is to restore their life after they have died - something generally dismissed as impossible. For centuries, humans have been intrigued by the eternal nature of death and how, perhaps, it may not hold such finality. Beliefs of rebirth, Gothic tales depicting supernatural beings reanimated, and even certain advances in science suggest that there are at least possibilities where one can, in rare cases, return from the dead.

Generally, when we state someone has died, we are referring to biological death. This means that all organs of the body are no longer working.

This however can be further simplifiedbiological death is the result after cortical death, when there is no more electrical activity in the cells of the brain, and clinical death, where the heart beating or breathing stops for over 4-6 minutes. Without the heartbeat, oxygen is not supplied to the organs vital for survival; yet, despite this, there is such a thing as reversible clinical death. Many organs can be restored even when left without blood circulation for hours, with the exception of the brain (usually using 15-20% of the entire body’s blood supply) that after only three minutes can sustain enough damage to lose some of its functions. After ten, some cells in the hippocampus - the part of the brain that stores memories - would begin a delayed death, not

actually doing so until as much as hours after resuscitation.

In many situations where the equipment is available, death is very closely prevented. An example of clinical death being reversed is defibrillation. Defibrillators used within five minutes of cardiac arrest (where the heart abruptly stops pumping blood) can revive someone. They work by delivering an electric current to the heart which either restarts the heart or restores its normal rhythm.

Some people who have been revived from reversible clinical death, and other life-threatening events in which their bodies were pushed to the very limits, have had unique experiences during them; survivors of near-death experiences claim that they have experienced what it is to die for a short period of time. What they describe to have occurred during these brief moments of passing are a mixture of interactions. Near-death experiences, or NDEs, are each unique; however, they all share several characteristics which many expect of death: a detachment from the physical body (out of body experiences), the awareness of being dead, ‘tunnel vision’ and intense emotions, often of peace and euphoria, though distress is possible too. A few of these can be explained by the knowledge we have of the human body in a more straightforward way; for instance, tunnel vision is caused by a lowering blood flow in the retina that in turn reduces peripheral vision.

In 1994, orthopaedic surgeon Tony Cicoria had a neardeath experience after being struck by lightning. He had been at a family gathering and was using a payphone during a storm when he was struck by a bolt of lightning. He recounts seeing his family interact with his body, performing CPR and calling an ambulance, however from an out of body perspective. Cicoria was surprised that he could hear and see as well as having the ability to think normally even when seemingly detached from his body; he even tried speaking to them, despite them not hearing him. Cicoria also remembers the moment he thought that this meant he was dead. He continued walking around, stating he could pass through solid objects and that he was immersed in bright light, feeling a strong feeling of peace, before waking up, in his body, on the ground. Cicoria was initially in pain and confused, however after doctors examined him they stated he was in good condition, and he returned to normal life two weeks after the incident.

There are many theories as to what causes this strange variety of experiences people have during NDEs. Some think it is the result of a loss of blood flow (ischemia) and oxygen (anoxia) causing parts of the brain to ‘shut down’ due to the usually consistent electrical activity in the brain being disrupted. The human mind often fills in gaps in memory, and, with the altered lack of input from a decrease in fully functional regions of the brain, it is likely that during an NDE that is what is happening. As well as this, past memories and beliefs may therefore heavily influence what is experienced, and, if remaining conscious, the person will find all of it feels real. Scientists have experimented with consciousness on highly trained pilots and astronauts with centrifuges. Five times the force of gravity results in blood not being delivered to the brain - such forces are difficult for the heart to pump blood against. The pilot would then faint, and they described that they went through events similar to those depicted by people who had had near-death experiences, including: out of body perspectives, senses of euphoria, tunnel vision, bright flashes of light and even dreams. It is likely, during an NDE, that the remaining functions of the brain unaffected by the ischemia paired with the mind compensating using the memory results in the variety of events present. If too much of the brain is affected, whatever remains of their consciousness will cease as well.

some continue to believe cryonics remains potentially viable in the future, as technology develops. As long as the structure of the brain is preserved well enough, its information should be recoverable and data restorable, even after long periods of time without activity; future nanotechnology may enable repair of any damage that the cryoprotectants could not account for. There are, however, significant obstacles, not least the damage caused by the formation of ice; thawing large organs can result in them splitting, ice fragments interfering with the connections between tissues and cells, the latter often shrinking with the concentrations of salt changing, negatively impacting their ability to function after restoration. The technology needed to repair the ice-damage, the effects of oxygen-deprivation, and the toxic damage from all of the chemicals (such as cryoprotectants) would have to be far more advanced than any we have at the moment. The expense of preparing and maintaining the conditions for the bodies are extremely high, making it unlikely that companies involved in cryogenics would last very long; many of the pioneering companies from the 1970s have gone out of business, in the process thawing and disposing of the stored bodies.

THE NEARERST WE ARE, CURRENTLY, TO A PHYSICAL RESURRECTION IS THE FIELD OF CRYONICS.

In 2016, a rabbit’s brain was nearly perfectly preserved by Robert L McIntyre and Gregory Fahy. It was kept in these ideal conditions at -135 degrees Celsius, and many of the microscopic details, such as the cell membranes, were also preserved by the method they used. This involved first suspending the neurons and synapses in the brain before cooling it. Furthermore, a chemical called glutaraldehyde was used, which is unfortunately toxic, and it would fix the proteins within the brain’s blood vessels in place as well as prevent decay, overall resulting in structurally stable tissue that could last hundreds of years. McIntyre called this technique the “Aldehyde-Stabilised Cryopreservation”. Fahy had experimented with this method in 2010 to try and preserve kidneys. However, this almost flawless preservation is yet to be perfected on larger mammals, which some cryobiologists see as their next goal.

The nearest we are, currently, to a physical resurrection is the field of cryonics, whereby the bodies of recently deceased human beings are stored at incredibly low temperatures (-196 degrees Celsius) in order to preserve them for decades, in the hope (on the part of the individual who has paid for their body to be frozen) that they can then be resurrected at a later date, when or if the technology to do so is developed. Freezing humans was an idea put forward by Professor Robert Ettinger in 1962. The first person to be preserved with cryonics was James Bedford in 1967; since then, over 200 people have been frozen in a similar way. The process for cryonic preservation must start immediately after clinical death. It involves applying cryoprotectants to the body; these prevent freeze damage to the cells and tissues. None of it has been successful so far, and it is regarded as pseudoscience. However,

There are many reasons as to why people may want to undergo cryonic preservation. Some who have severe, currently untreatable illnesses hope that they can be cured in the future, but will not live long enough to reach it, and so wish to be preserved instead. Others may want to be resurrected in the future and to get the chance to experience it. Complete resurrection is currently impossible with cryonics; therefore, for the moment, some scientists are instead aiming to preserve the neurons and synaptic connections, and potentially the memories too - synapses develop in size as we learn and make memories. It is possible that if kept in good condition, in the future the memories’ information could be ‘uploaded’ from them, therefore resurrecting someone's experiences rather than their body and consciousness.

In conclusion, although the complete resurrection of a longdead being remains fiction for now, our advances in science and technology enable us to survive pushing our bodies to the very edges of life, even into fleeting moments of death and perhaps into the future, where it is likely that more will be possible.

THE COMEBACK IS ALWAYS STRONGER THAN THE SETBACK

REDEMPTION WELDS TOGETHER THE TEXTS OF THE BIBLE AS A THEMATIC WHOLE.

RREDEMPTION REDEMPTION R

edemption is at the heart of Christian belief and thought. In the Gospels and in the letters of Paul, Christ is presented as purchasing our freedom by paying a ransom, giving his own life in payment. In doing so, he secures our deliverance from sin in an act of salvation. The word comes from the Latin “redemptio”, meaning “to buy back”; it was often used to describe the process whereby someone could buy a slave’s freedom so that the slave became a free man or woman. Indeed, the Bible, as a whole text, can be seen as a narrative of redemption. The first Book, Genesis, begins with the story of humanity’s fall, through the story of Adam and Eve and the taking of the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, breaking the human relationship with God, the Creator, Himself. The Christian interpretation of the Old Testament, and the Christian New Testament, suggest that God has a plan for reconciliation, which involves redeeming us from the Original Sin of Adam and Eve’s disobedience. Within the larger Christian narrative arc of Christ being sent by God, his Father, to sacrifice His life in redemptive payment, there are other, individual narratives - smaller sections of salvation - that, pieced together, paint a whole picture of redemption. Significant figures in Jewish scripture, including Abraham, Jacob, Moses and David, each commits sin and then comes to a state of repentance before being forgiven by God. We see how this welds together the texts of the Bible as a thematic whole; in order for this idea to work in the bigger picture, it must operate on an individual

basis, too. For instance, in Ephesians 1:7-8a Paul states: ‘In him we have redemption through his blood, the forgiveness of sins, in accordance with the riches of God’s grace that he lavished on us.’ Paul’s use of the word ‘redemption’, referring to the paying of a price or ransom, presents Christ’s blood as the price paid for us, for our redemption. This forgiveness of our sins is part of our redemption from that human frailty originally symbolised by Adam and Eve’s act of transgression that led to physical mortality and spiritual bondage. That bondage is now redeemed by Christ’s blood. Thus, we are not only freed from the consequences of our sins, but liberated from the penalties that human life itself puts on the table.

Despite, or because of, the origins of this notion in Christian belief, the idea of redemption remains central to our contemporary culture, from film narratives to tales of famous figures transformed into more convalescent beings. It is a concept that continues to shape many of the lives on this planet, for better or worse. The recent Beckham documentary, centring on the former England footballer David Beckham, is a prime example of redemption placed in a more contemporary context. With the fame that sporting stars already hold when they advance through their journey of athletic stardom, they are often seen to fall from their former grace - whether over a period of days, weeks, months or years. For the reputation Beckham had built for himself to break into pieces and fly in front of his eyes, all it took was a secondand an unnecessary flick of his right boot. In the timeframe of moments, the face, the fame, and darling of the nation became Public Enemy Number One, as England faltered out of the 1998 World Cup following his red card against Argentina. Not only

was the shame of letting his country down put upon the young man’s shoulders, his whole life suddenly became a burden; effigies of Beckham were hanged and burned outside pubs all across England, and his face was plastered on dartboards situated on the front cover of a national newspaper. Death threats were issued. Although he was experiencing this severe mental trauma at the time, the footballer, incredibly, continued to maintain a sound performance for his team, Manchester United, with Beckham still being a treble winner after his moment of horror for England. At the heart of the idea of redemption is the belief that ‘the comeback is always stronger than the setback’. This is certainly true of Beckham’s redemption. His deliverance mirrored his downfall, happening in a matter of seconds. A free kick awarded with only seconds remaining, Beckham stepped up to the mark and sent a beautiful ball curling into Greece’s goal, driving England through to the 2002 World Cup. With a quick swing of his boot, the footballer regained his reputation and his honourall by one action. ‘The kick was about drawing a line under four years of abuse, four years of bitterness,’ said Beckham; he had completed his own redemption story.

Redemption is at the heart of so many of our most popular stories, in fiction as much as in real life. It knits a narrative into a garment of depth and texture, allowing the layers of a character to be slowly peeled back to unearth a psychological and moral depth that resonates with the reader long after they have finished reading the story. Severus Snape is perhaps the most complex character in the entire Harry Potter series, and one of the most beloved, because of his redemptive arc. The narrative keeps us guessing, until the very end of the final novel, as to whether Snape is on the side of good or evil. He is presented as mercilessly bullying young Harry in every book, seeming to conform to the stereotype of a villain. However, for the reader, patience is key to discovering Snape’s

true intentions, which reminds us that patience and forgiveness are at the heart of the idea of redemption. Snape is certainly a flawed character; pretending to serve Voldemort while having his true loyalty lie with Dumbledore, Snape is driven by a sense of guilt. Not least, he is haunted by having told Voldemort of a prophecy that then sealed the fate of Harry’s mother Lily, who was the love of Snape’s life. Snape sacrifices his own life, in the final novel, in an act of atonement.

Atonement, like redemption, is a Christian theological term. Atonement is a key part of the act of redemption, a making of amends for an injury or wrong caused to another. Salvation can only be achieved following atonement. Snape shows atonement by devoting his life to defeating Voldemort, which necessitates having to pretend to be a Death-Eater. His willingness to be completely misunderstood, and even hated, by others (with the sole exception of Dumbledore) is what gives Snape’s character such moral power and what makes him so memorable to readers. This is why he is ultimately loved by readers of the novels - and admired by Harry himself. This is what makes Snape’s redemptive arc, his character development, so impactful. He exemplifies the central idea that we can be delivered from our sins, saved from our own setbacks, through an act of atonement and redemption.

Thus, whether biblical, biographical or fictional, this redemptive belief remains a central human narrative, whether describing how Christ ransoms and restores us as human beings on this earth, how a flawed sporting hero comes back from professional disaster, or a complex character evolves within a novel to evoke intrigue and awe. Redemption pieces all of this together. Redemption drives us forward, although it comes from a place that draws us back.

ASBURY AND JESUS FREAKS

HOW RELIGIOUS REVIVAL SHAPED THE LAST CENTURY

Oscar Mellers YEAR 12

Christian religious revival has been surging through the United States in the last year, with the Asbury Revival being placed front and centre, as one of the largest movements in young people that the Church has seen in a long time. The significance of religious revival is a topic that is considerably important to many believers within the Church today, but primarily the Pentecostal sect (who believe in Baptism by the Holy Spirit, receiving gifts such as prophecy, or the speaking or interpretation of tongues), who think that the Kingdom of God is able to move, or expand, to a greater degree with an uptake of faith. They further believe that the growth in believers is a sign of the end times described in the Book of Revelation (see Matthew 24:42-44, which announces that the Gospel will be preached in all nations before the end times, hinting at an increase in belief). Therefore, it can be argued that religious revival is one of the most significant events that could take place within the global Church.

The 2023 Asbury Revival began on 8th February, in Asbury

University, Kentucky, when some students spontaneously remained in the chapel after one of their regular scheduled services. The president of the university promptly sent out an email, inviting students to join the worship session. This became a global phenomenon, as it was shared on social media, with people praising God for the things they had witnessed, with particular popularity among Generation Z, the group most present on social media. Gen Z’s distinctive priorities are reportedly a desire for more authenticity in their Christian worship, as opposed to production (meaning lighting, sound and pre-planned worship sets). In the last two decades, we have seen a growth in so-called ‘mega churches’ in the United States, some with congregations in the thousands attending stadium-like church buildings. In these meg-churches, capital is pumped into lighting sound (and, sometimes, smoke machines). They feature bands who have become famous and released their music worldwide, for example Bethel Music (of Bethel Church, CA) and Hillsong Worship (of Hillsong Church, Sydney). Preachers and pastors in these churches have gained significant online presence, such as Bill and Beni Johnson (the latter recently deceased) as well as Kris Vallotton. Gen Z desires a move away from such productionheavy mega churches towards spontaneous, ‘spirit-led’ worship sessions such as the one at Asbury. People have come across the world in huge numbers to witness what has been occurring within Asbury University; eventually, doors had to be shut to anyone but students.

Religious revival is marked by upheaval within the Church, which many believers tend to describe as a ‘shaking,’ or, most recently, ‘the end of the hallway’. This metaphor was introduced by modern-day prophet, Craig Cooney, who explains ‘God doesn’t close one door without opening another’ and notes that the hallway in the middle is not discussed. The Church globally has been described as in a time of waiting for the last few years, in that many senior leaders, prophets and preachers do not know where God might be taking the Church. They have seen that, as a whole, pre-Covid styles of worship no longer exist, but they are not sure what does exist now. However, they are certain a time of revival is present, and that the ‘end of the hallway’ has been reached, or that the Church is undergoing a ‘shaking’. In England, their evidence for this is the 2023 February General

Synod, where there was disagreement whether or not to bless same-sex marriage within the Anglican Church. Since then, many Church leaders have discussed the possibility of splitting from the Church of England if such a blessing is to pass, forming a Southern Anglican administration under its own control rather than that of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, or that of local bishops and deans. This potentially dramatic change in the English Church is seen as further evidence of the church’s shaking. In America, the death of Beni Johnson, and the stepping down, or the removal from power, of many church leaders, including Mike Pilavachi, after recent investigations and revelations, have also been identified as marks of revival.

There are some echoes, here, of the Jesus Movement, which gained traction in the 1970s, particularly among the ‘Hippy’ community, having begun in California in the late 1960s and quickly spread across the globe. Members of the movement were branded ‘Jesus people’ or even ‘Jesus freaks'. It was born out of the Charismatic Movement, which had begun a decade earlier, focused on a return to a ‘more Biblical Christianity’, where the Church revisited the often-forgotten things in the Bible, primarily Baptism in the Holy Spirit or Baptism in Fire (metaphorically), through which people would begin to gain spiritual gifts which allowed for a new way of spreading the Gospel message across the globe. Spiritual gifts, or Charismata (from the Greek) included speaking in tongues, the interpretation of tongues, the giving of prophecy, words of wisdom or of knowledge, and even boldness of faith. In biblical tradition, these traits are first seen on the Day of Pentecost, fifty days after the ascension of Jesus Christ (see Acts 2:1-13). In the past, Roman Catholic and Anglican churches had often ignored this episode, seeing such spiritual gifts as performative, not part of mainstream Christianity, despite their presence in Biblical scripture. In the 1960s, the Charismatic Movement aimed to reintroduce charismata to churches which had forgotten them, fundamentally changing the way many people worshipped.

The Old Testament prophet, Ezekiel, recalls his experience of revival in the Valley of Dry Bones. God tells Ezekiel to prophesy life over the bones, and that they will be brought to life. Ezekiel does so, and the bones form bodies, which gain muscle and become regular living creatures. At the end of the account, God tells Ezekiel that his people Israel have gone astray, that they lack hope and a future, but God will breathe life back into them. This story is one of revival: the dead, and decomposing bones are brought from a state of nothingness to life. Many Christians seek to apply this story to the revival in the Church today, and the events

that took place in the valley are representative of how revival shapes the Earth. Many in the Church see upholding the same forms of worship as important, and that maintaining biblically accurate tradition is a duty. However, a growing proportion of the Church recognises that, in many places, the fullness and variety of worship that the Bible describes is not often expressed. Many churches ignore dance as a form of worship (see 2 Samuel 6:14), and until the Charismatic Movement, many ignored the gifts of the spirit. Therefore, the Church views revival as crucial: it is a way for Christians to discover new aspects of their faith, so that the Kingdom of God can grow.

With worship being placed front and centre during times of revival, it is important to consider its main purposes in the Christian faith: to give glory to God for his work (including healing, freedom, rescue from dark places) and his unchanging nature whilst recognising His difference from the world, and also to receive sanctification. Christians aim to be more like Jesus, living a life like his; and sanctification is simply that. Therefore, whilst worship is an opportunity to give thanks to God, it also allows Christians to get to know their God, understanding him so they can grow in likeness to Christ. Therefore, during times of revival, as the ways in which Christians worship change, so too do their results of worship. Many followers of Christ report that finding new ways to bring glory to God also changes the way in which they experience God, leading to new messages from him. Therefore, in times of revival, it can be argued that God reveals new things, leading to further dramatic changes within the Church as a whole, based on individual encounters. This therefore proves the significance of religious revival in the Church today, as it allows a more current experience of God as different people begin to speak of their new experiences with God.

GEN Z'S DISTINCTIVE PRIORITIES ARE REPORTEDLY A DESIRE FOR MORE AUTHENTICITY IN THEIR CHRISTIAN WORSHIP.

Therefore, it is clear to see that religious revival continues to be the driving force of the Christian faith. As long as new people claim to experience God, and the Gospel message is accepted in different ways, the Church across the globe will continue to grow, despite the periodic ‘shaking’ which it undergoes. Overall, the significance of religious revival will always be extremely high.

Reading , REVOLUTION AND Religion

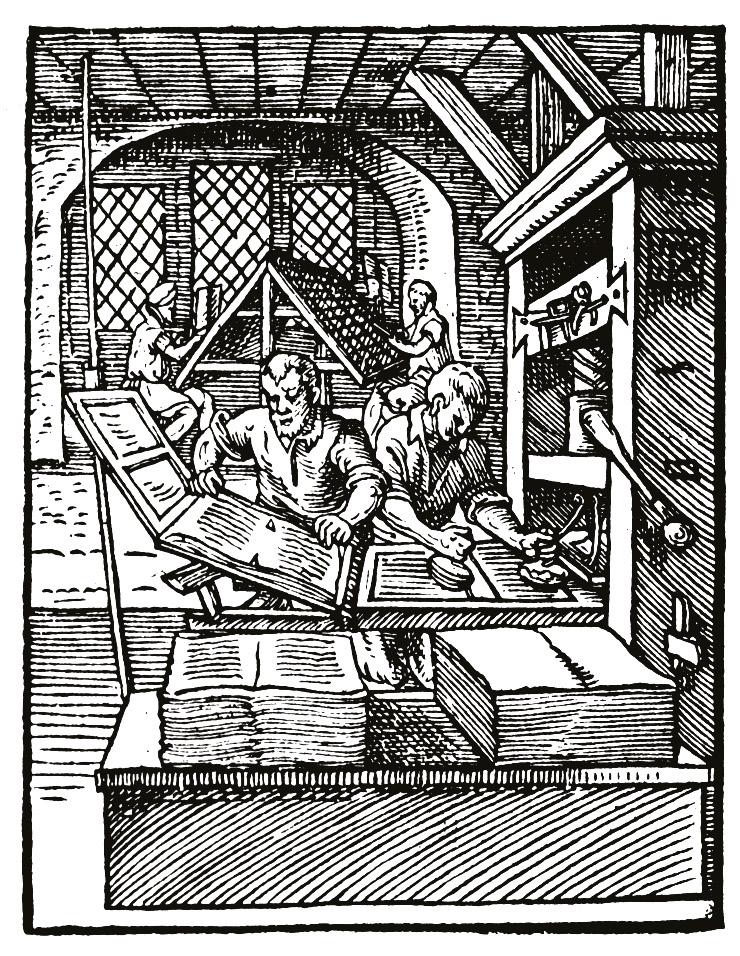

THE TEMPESTUOUS IMPACT OF THE PRINTING PRESS

Nora Rechel ORGAN SCHOLARTHE 1455 GUTENBERG BIBLE, THE FIRST SIGNIFICANT BOOK PRODUCED USING MOVEABLE TYPE, WAS THE BEGINNING OF THE 'INFORMATION REVOLUTION'.

One could argue with the utmost panache that the Renaissance symbolised the paragon of human development, finally moving Europe away from the outdated ideas and beliefs of the Mediaeval era, and coaxing in the beginning of modernity - stimulated by the rapid development of art, literature, science, and music. As outlined by historians like Diarmaid MacCulloch and T. M. Lindsay, the Renaissance (and accompanying Reformation) symbolised the beginning of an age of rapid social evolution and transfer of ideas that had not been

observed in Europe since Classical times. Having emerged in the Mediterranean region, with Florence as the authoritative central hub of cultural progress and learning, the ‘Northern Renaissance’ in 15th to 18th century Western Europe formed a multitude of national and regional variations of original Renaissance ideas.

In England, the Elizabethan era denoted the height of the English Renaissance movement, although seeds of cultural advances and educational pursuits (such as the founding of Eton College and King’s College Chapel by Henry VI during the Wars of the Roses) could be observed from the early 15th century. Fundamentally, the Renaissance encompassed a return to classical ideas and original biblical texts; the stability and longlasting influence of Ancient Rome was sought after by modern scholars, following centuries of mediaeval warfare and perpetual

religious turbulence. The invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg by 1450 was arguably the most critical factor in making new scientific hypotheses accessible to the literate, and facilitating the easy spread of political and theological ideas. Libraries began to open to the public, and extensive collections of new books were displayed to foreign visitors in palaces across Europe.

The 1455 Gutenberg Bible itself - the first significant book produced using moveable type - is recognised as the essential stimulant for the beginning of the ‘information revolution’ that occurred during the Reformation. The acceleration of the production of printed books directly contributed to the foundation of new universities such as Mainz in 1477, helping to dismantle the convention of reading being a discipline reserved for the educated elite. Despite access to books being primarily urban in nature, and most early books being of a religious quality, the Reformation observed a strong correlation between literacy and education, with the price of books falling by 2/3rds just between the years 1450 and 1500. In England, William Caxton (sponsored by self-made magnate and bibliophile Anthony Woodville) was responsible for introducing the printing press in Westminster in 1476; among his first publications were a copy of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales and a translation of Aesop’s Fables. Caxton’s printing press was especially influential, as it catered for the standardisation of the English language by officially adopting the London dialect in ‘Chancery Standard’, and establishing directives for standard English spelling. As historian Marilyn Gilmore asserted in 1952, ‘printing drove the most radical transformation in the conditions of intellectual life in the history of western civilisation’. Perhaps most importantly, the metal moveable-type printing press secured the triumph of the vernacular over Latin - something that would prove fundamental during the propaganda-

rife religious turmoil unleashed by the Reformation.

However, despite the seemingly unanimous acceptance of Renaissance advancements in the form of the popularity of new plays by William Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe, the traction of compositions by composers like William Byrd and Thomas Tallis, and the tentative beginnings of the Age of Discovery, new reformist philosophies surrounding theology and social order remained controversial and offensive to many. As described by historian Stefania Tutina, the Renaissance and Reformation were ‘parallel but intertwined’ movements, with both threatening the authority of the Vatican - already in decline since the fiasco of the Western Schism from 1378 to 1417. Ultimately, the extent of divisive religious and social outlooks culminated in the beginning of the Counter-Reformation by the early 16th century, constituting a furious Catholic backlash reaction to the progressive ideals propagated by Protestantism. It is undoubtedly the case that the theological war was fuelled and escalated by Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press, with both Protestant and Catholic propagandists making use of the new medium to spread their beliefs and win support.

In this way, the printing press was fundamental to the early development of Renaissance humanism; this philosophy forming the basis of reformist thought that resulted in Martin Luther’s nailing of his 95 theses to the doors of the University of Wittenberg in 1517. Gutenberg’s invention allowed for the spread of Reformation literature and humanist ideas throughout the latter 15th century, allowing for the musings of the likes of

Poggio Bracciolini and Lorenzo Valla to become accessible to a greater European audience. Desiderius Erasmus - the famous Dutch humanist who died in 1536 - profited sincerely from the printing press, establishing a close relationship with Swiss publisher Johann Froben in Basel. This allowed for the publication of over 200 works of his, resulting in the circulation of modern Reformation theory across the continent. Similarly, in England, William Tyndale used Gutenberg’s technology in order to complete an English translation of the Bible, one decade after Martin Luther’s 1522 German version. Whilst English reformists welcomed the new translation, it was still met with unease and conservative outcry - particularly due to Tyndale being heavily influenced by Lollard ideas, especially strong in his home county of Gloucestershire.

Originally, ‘Lollard’ was used as a derogatory term for members of the ‘proto-Protestant’ Lollard movement that emerged during the late 14th century in England, influenced by the writings of John Wycliffe. Lollards made a number of early demands that were to form the basis of Reformist principles: widespread reform of the clergy, eliminating corruption within the Catholic Church, producing a translation of the Bible into the ‘Middle English’ vernacular, extinguishing superstitious practices, and an ‘ad fontes’ return to the original biblical scriptures. Wycliffe himself swiftly amassed a following for preaching outspoken critiques of Catholicism at Oxford University, but was soon targeted by the authorities for his implied involvement in the 1381 Peasants’ Revolt. Similar persecution of Lollards could be observed in a 1401 Act under Henry IV equating Lollardy with sedition, and the 1410 burning of John Badby for denying the existence of transubstantiation. With the invention of the printing press in 1450, persecution of Lollards accelerated as new theological ideas spread faster than ever before: in 1461, Welsh priest Reginald Pecock was exiled in Thorney Abbey and saw his books being burned in front of him. Furthermore, the Lollard movement was driven literally underground, with the formation of ‘underground reading parties’, and reformists becoming even keener to access forbidden books - like an East Anglian Lollard who paid 4 marks 40 pence for a New Testament. By the 1520s, Lollardy had been absorbed into early Protestantism, with Lollard publications forming the basis for the reformist school of thought.

cities had printing centres, meaning the novelty and controversy of Luther’s actions could spread promptly across the continent. The discipline of printing itself also linked conveniently to the beginnings of market capitalism, with printmaking becoming a standardised call of work for many living in cities. Radical reformist actions such as the Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII were deftly met with Catholic propaganda and protest. In response, the Catholic Church accelerated the publication of literature surrounding church doctrines and correct practiceintending to draw more people to services. The printing press also permitted the manufacture of new guidance manuals for Catholic ministers and the production of satirical woodcuts; a particularly famous 1529 example portraying Luther as the antichrist. However, Catholic propaganda relied primarily on preaching in order to convey ideas orally - something that arguably disadvantaged them in the propaganda war. Meanwhile, reformists used the distribution of printed pamphlets as the principal method of gathering supporters, with Luther himself completing over 2200 printings in total. Despite literacy remaining low throughout the 15th and early 16th century, it has been argued that the Catholic cause suffered significantly due to the church not being able to keep up with the sheer volume of reformist printing during the Reformation.

It is an accepted fact that access to knowledge and books is enlightening, and is seen by some as an attack on their superiority. Reading challenges individuals’ worldview and blind obedience to authority; it offers new perspectives on difficult issues, and in the case of the Reformation, it changed the course of European history forever. Particularly in the 21st century, with the rise of social media facilitating the rapid spread of ideas across borders, knowledge is power. Perhaps this is a reason why (as of 2022), 7 countries ban Facebook, among them 4 suspected nuclear weapon states and 2 members of the United Nations Security Council. The continued controversial use of social media in the form of ‘fake news’, cyberhacking, and censorship also emphasises how radical the influence of mass media remains today, over 550 years later.

By the year of Luther’s 95 theses in 1517, 200 European

Gutenberg’s fundamental contribution to civilisation is perhaps best summarised by American author Mark Twain: "What the world is today, good and bad, it owes to Gutenberg. Everything can be traced to this source, but we are bound to bring him homage, … for the bad that his colossal invention has brought about is overshadowed a thousand times by the good with which mankind has been favoured."

“History Has Its EyesOn You”

THE LASTING LEGACY OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION

For many, the American Revolution is either a distant, forgotten history lesson or the topic of a modern musical, Hamilton. And yet, its legacy on the history of the world has been monumental, whether we realise it in our everyday lives or not.

The American Revolution’s most immediate impact was on the French Revolution; together, these seminal, eighteenth-century events set a precedent for political leadership and governmental morals the world over. Furthermore, the American Revolution had an enormous effect on the international relations between the newly-formed United States of America and other countries, not least Great Britain, its antagonist in the War of Revolution; as individual Americans changed status, from colonists to citizens, their sense of themselves was transformed, shaping modern American identity. The relationship between the two nations, USA and UK, improved quite swiftly and they became strong allies, that partnership essential during two World Wars, particularly the relationship between Franklin D Roosevelt and Winston Churchill in

THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION LEFT A POWERFUL BLUEPRINT FOR THE CREATION OF A MODERN, DEMOCRATIC NATION-STATE.

defeating the Axis nations. At the same time, the severing of ties between America and Britain allowed Americans to prosper and eventually create a global superpower that superseded Britain, and, by the end of the Second World War, held the future of the world in its hands as it faced a new antagonist in the form of the USSR (the Soviet Union). The Cold War, lasting from the late 1940s to the late 1980s, could have been catastrophic, dominated by two nuclear powers, but ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1988, leaving the USA the sole global superpower.

The American Revolution was seen by leaders such as Thomas Jefferson as an example of a successful uprising against an authoritarian style of government. Jefferson was the principal author of the Declaration of Independence, in 1776, a successful example of a new set of governing morals which later inspired the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in France. Jefferson himself was later America’s ambassador to France, which

had been the first ally of the American revolutionaries, sending vital supplies and troops, as well as offering crucial naval support. This also gave French soldiers, such as Lafayette, first-hand experience of revolutionary warfare, which later proved invaluable in their own overthrow of the French monarchy and the aristocratic elite. America’s experiences showed the French revolutionary thinkers and leaders that previously impossible-seeming ideas, such as elected representatives, the separation of governmental powers and accountable leaders, were attainable. The French Revolution, and its Napoleonic aftermath, had a significant influence across Europe and the world, which, along with the American model, left a powerful legacy and blueprint for the creation of a modern, democratic nation-state.

The birth of the United States of America gave Americans a renewed sense of national character and reputation within international relationships. In the mid-18th century, before the revolution, Americans were colonists, with a relative sense of inferiority in comparison to those people living in Britain, the mother country. Increasingly, those living in America felt misjudged, misgoverned and exploited. As they were an ocean away from British society and politics, the two populations gradually branched into two very separate, different societies, so that ultimately a clash over political representation and governmental power became inevitable, resulting first in military

repression by the British government and then a violent backlash from American colonists, under the military leadership of George Washington. Military victory over the most powerful nation in the world, Britain, gave the Americans, now citizens of their own country rather than colonists subservient to another country, pride in their achievements. Eloquent writers such as Jefferson and British-born Tom Paine helped Americans see themselves as trailblazers in valuing liberty and democracy over monarchy and empire. However, some English writers of the time, such as Samuel Johnson, saw these values of freedom as hypocritical, as many of the leaders of the American Revolution were slaveowners; Johnson noted, “The slaves should be set free, an act which surely the lovers of liberty cannot but recommend.” Slavery was not abolished in the USA until 1865. Today, many people still quite reasonably question why men such as Washington and Jefferson continue to be portrayed as innovators of freedom when slavery remained a major part of the American social and economic structure for nearly a century after the Revolution they led, at complete contrast with the principles of liberty they advocated in such documents as the Declaration of Independence

H owever, America’s role in both the First and Second World Wars helped cement its image as an upholder of freedom and democracy. In 1917, America entered the First World War, three years after it had begun, on the side of Britain and France, partly influenced by German plans for an attack on the USA via

Mexico. By the end of the war in 1918, four million Americans had crossed the Atlantic as soldiers; there were 116,708 American casualties by the end of the war. In 1941, American troops once again crossed the Atlantic (and this time the Pacific) in support of the Allied powers, including Britain; America’s military and economic might contributed significantly to the eventual victory over the Axis powers led by Germany. One reason that the United States was relatively late in entering both world wars was the power of the Isolationist movement in America, with many citizens and politicians reluctant to involve American resources and personnel in what were perceived as European problems. However, President Woodrow Wilson, in 1917, and President Franklin D Roosevelt, in 1941, were influential in persuading ordinary Americans to abandon isolationist policies and neutrality in favour of siding with the Allies. Roosevelt’s close personal relationship with Churchill seemed to symbolise a particularly friendly relationship between America and Great Britain, which has been in effect since the early nineteenth century and has proved beneficial for both nations, rooted in Britain’s original development of 13 colonies along the eastern American seaboard in the 1600s and 1700s.

THE IDEOLOGICAL RIFT BETWEEN THE CAPITALIST UNITED STATES AND COMMUNIST SOVIET UNION LED ALLIES TO BECOME ANTAGONISTS FOLLOWING THE DEFEAT OF HITLER.

The other important alliance America formed during the Second World War was with the Soviet Union, led by Joseph Stalin, which was its main military partner in defeating Nazi Germany. However, the ideological rift between the capitalist United States and communist Soviet Union, led allies to become antagonists following the defeat of Hitler. The two nations, and ideological systems, were in contention for the role of global superpower, particularly following Britain’s decline from that status by the 1940s. The tension between the USA and USSR, lasting forty

years, was termed the Cold War, because it never became ‘hot’ (a term to describe two opposing sides directly fighting each other on the battlefield). Instead, it took the form of a series of proxy wars, in spheres from Cuba to Vietnam. Perhaps the factor that most contributed to the war remaining cold was that each superpower, USA and USSR, was a nuclear power, which meant that war would lead to “Mutually Assured Destruction” (MAD). The leaders of both nations were desperate to avoid descending into nuclear war, which forced the USA to remain engaged in international relations, in contrast to the isolationist policies of the early twentieth century. America now saw itself as having a duty to lead the Western sphere of influence and to act as a broker of power and peace across the globe.

America’s ‘soft power’ (cultural influence) has been as important as its ‘hard power’ (military and economic) over the past century. Just one recent example is the global success of the groundbreaking hit musical Hamilton, in 2015, which has renewed the global appeal of the story of the American Revolution by revolutionising (pun intended!) musicals as an art form. Lin-Manuel Miranda's radical mix of rap, R&B, jazz and classic musical theatre has shown audiences the story of the ‘Founding Fathers’ in a new way. An estimated 7.8 million people have watched a production of the musical (including its unprecedented streaming on Disney+), with the further effect of shaping how the American Revolution is now taught in schools across the world. Thus, the American Revolution has had a historical legacy that perhaps even Thomas Jefferson could not have predicted, from political structures to military alliances and musical theatre, cementing itself as one of the most transformative events in the Earth’s 4.5 billion years of history.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

https://www.history.com/news/how-did-the-american-revolution-influence-the-french-revolution

https://history.state.gov/milestones/1776-1783/french-alliance#:~:text=Between%201778%20and%201782%20the,protected%20 Washington's%20forces%20in%20Virginia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_United_States_(1776%E2%80%931789)

https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2017/summer/feature/world-war-i-changed-america-and-transformed-its-role-in-internationalrelations#:~:text=The%20American%20Expeditionary%20Forces%20arrived,116%2C708%20had%20lost%20their%20lives.

https://hamiltonmusical.com.au/about/#:~:text=Featuring%20a%20score%20that%20blends,on%20culture%2C%20politics%20 and%20education.

https://www.nexttv.com/news/disney-plus-hamilton-viewership-exceeds-those-whove-seen-it-live-research-company-says https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/resource-library-age-earth/

https://www.state.gov/u-s-relations-with-united-kingdom/#:~:text=The%20United%20States%20has%20no,two%20countries%20 established%20diplomatic%20relations

“SOMETIMES, HISTORY NEEDS A PUSH”

THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTIONS

Abriti GhimireYEAR 10

Two nations dominated the twentieth century: the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. They were, briefly, allies in defeating Hitler’s Nazi regime in the 1940s. However, for the most part the USA and USSR were antagonists, divided in terms of geography but also of ideology: capitalism versus communism. Two tumultuous revolutions, in 1905 and, even more consequentially, in 1917, marked significant turning points not only in Russian history but in global history, leading to profound political, social, and economic changes that shaped international relations for decades. This article provides a comparison of how these revolutions transformed Russia and the world, examining causes and consequences.

The Russian Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905, often referred to as the "First Russian Revolution," was a precursor to the more famous 1917 Revolution, laying the groundwork for later revolutionary movements and serving as a catalyst for political change in the Russian Empire.

of political freedoms. The Tsar's government disregarded calls for political reform, further fuelling dissent.

The social pressures at home were exacerbated by Russia’s defeat by Japan in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, a consequence of Russia's imperial ambitions coming into conflict with those of Japan. The humiliation of military defeat and the resulting economic strain helped intensify discontent as citizens saw their government's inability to protect their interests.

TWO TUMULTUOUS REVOLUTIONS,

IN 1905 AND 1917. MARKED SIGNIFICANT TURNING POINTS NOT ONLY IN RUSSIAN BUT IN GLOBAL HISTORY,

Economic disparity and social injustice were prevalent in the Russian Empire. A majority of the population, especially peasants and industrial workers, lived in abject poverty while the nobility and bourgeoisie enjoyed significant privileges and wealth. The autocratic rule of Tsar Nicholas II was characterised by political repression, censorship, and a lack

On 9 January, 1905, thousands of protestors, led by Father Gapon, marched to present a petition to the Tsar. Hundreds were killed or wounded, when the Tsar’s troops opened fire. This was a turning point, galvanising public anger and fuelling revolutionary fervour. Soon, major cities like St Petersburg saw widespread labour strikes and protests, with workers demanding better wages and working conditions, as well as political reforms. Some workers formed workers’ councils, known as "soviets"; the St. Petersburg Soviet became a particularly important centre for revolutionary activity.

Fearful of revolution, Tsar Nicholas II issued the October Manifesto in 1905 in order to satisfy some of the demands being made by the soviets. Firstly, it announced the establishment of a State Duma, a parliamentary body that granted some political representation; however, it had limited powers. The Tsarist government also enacted land reforms, allowing peasants to gain land from the nobility; it marked a step towards change, but did not fully resolve agrarian issues. Therefore, the 1905 Revolution and Tsarist manifesto resulted neither in substantial political nor in economic reform, but did temporarily ease tensions, allowing the regime to regain control. Discontent among the masses only continued to grow, as the 1905 Revolution had raised expectations without fulfilling them. As it turned out, 1905 was a mere prelude; the main act would take place 12 years later.

The Russian Revolution of 1917

What is now called “The Russian Revolution of 1917” is better understood as two separate revolutions: the “February

Revolution" and the "October Revolution". The latter event, in particular, represented a watershed in world history.

Again, war was a key factor in shaping revolution. Tsarist Russia was fighting in alliance with France and Britain against Germany, and the badly-led, ill-equipped Russian army sustained huge casualties on the Eastern Front, causing discontent in Russia. In addition, the war imposed economic hardship on ordinary Russians, including food shortages and crippling inflation. However, attempts to protest by ordinary people were met by political and military repression on the part of the Tsarist government, along with censorship.

In February, 1917, discontent spilled over into large-scale protests and strikes, particularly in St Petersburg. The Tsarist government lost control of the situation, leading to the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II and the resignation of his government. Democratic Opposition politicians, led by Alexander Kerensky, formed what became known as the ‘Provisional Government’, designed to take care of governing the country while formal, democratic elections, under a new constitution, took place. Kerensky and others envisaged modelling Russia along the lines of European democracies such as France.

H owever, Kerensky’s government was unable to improve either the war situation or the state of the Russian economy. In addition, the unelected Provisional Government was seen by many people as illegitimate. Eight months after its formation, it lost control, just as the Tsarist government had before; Kerensky was forced to flee the country. A relatively small group, the Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, took advantage of the chaos to seize power, establishing a communist government, which very quickly initiated a radical transformation of Russian society. “Sometimes”, wrote Lenin, “History needs a push.”

had achieved complete political control within Russia, through a combination of economic reform, political manoeuvring, and violent repression. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was formed, which remained in existence until its formal dissolution in 1991. Lenin and his successor, Stalin, transformed Russia into a modern, industrialised state, and a global superpower. However, the human cost was astronomical, with an estimated 6-9 million Russians dying as a direct result of Stalin’s repressive policies from the 1920s to his death in 1953.

A Comparison of the Revolutions of 1905 and 1917: Both revolutions were rooted in economic hardship, political repression, and social inequality, exacerbated by military failure: the defeat of Russia by Japan in 1905 and the stalemate on the Eastern Front in 1917.

The Tsar and most of his family were arrested and imprisoned; within a year, they were executed, marking the end of the Romanov dynasty. The Bolsheviks negotiated a swift armistice and peace with Germany, ending Russia’s involvement in the unpopular war. However, very soon, a brutal civil war erupted within Russia, as the Bolshevik-led Red Army faced off what became known as the White Army led by former Tsarist officers, supported by Western, capitalist countries such as Britain and the United States who feared the establishment of a communist state in Russia. After a protracted civil war, the Red Army triumphed militarily. Meanwhile, the Bolsheviks

However, whereas there was a lack of unified and organised revolutionary leadership in 1905, in October 1917, the Bolsheviks, under Lenin, provided an organised leadership structure, focused agenda, clear ideology and ruthless readiness to repress opposition. Whereas the Duma, established in 1905, gave very limited powers to those opposed to the Tsarist government, the Bolshevik movement in 1917 quickly seized the levers of government themselves, gaining total control very swiftly and purposefully, enabling Lenin and Stalin to enact a profound socio-economic transformation and the Soviet Union to shape global politics and ideology throughout for the 20th century, including playing a decisive role in defeating Hitler, again on the Eastern Front, in the 1940s. However, as noted, the human cost of Stalin’s regime, in particular, was brutal. Although the 1905 Revolution ultimately failed, it did shape the more successful revolution that took place 12 years later, in October 1917. These two revolutions, each driven by unique circumstances, serve as crucial chapters in the complex, multifaceted and ongoing story, not just of Russian, but of global history.

RETALIATION, RETRIBUTION or REVENGE?

NAVIGATING THE DIFFICULTIES IN ISRAEL AND GAZA

Diarmuid BaileyYEAR 13

On October 7, 2023, Hamas, a militant terrorist group based in Gaza, launched a surprise and unprovoked brutal attack against Israel killing 1,300 people, injuring 3,300, and taking 200 hostages, many still to be released. This is not the first time that Israel has been a victim of this group and so their reaction to this event was expected by many. The attack caused a full-scale bombardment of the 25-mile long, 7-mile-wide area of land known as the Gaza Strip, home to 2 million Palestinian people and the place where Hamas is based. In this article, I will attempt to explain some of the background to current events in Israel Palestine. As a student of history, I believe we cannot begin to understand the present without some grasp of the past. My intention is not to act as a moral judge, or to cast blame, but rather to explain why both Hamas and Israel have acted how they have in recent days and weeks.

THE HISTORY OF THE REGION IS COMPLEX, ROOTED IN THE HISTORY OF COLONIALISM.

There are many questions not only to the legality of Israel’s response but also concerning the impact of Israel’s 16-year long blockade on Gaza since 2008 when Hamas took control in Gaza.

Since 2008, up to and including the current situation in Israel and Gaza, over 15,000 Palestinians have been killed and 1,600 Israelis have been killed. Since 7th October, over 8,000 Palestinians are confirmed dead (at this time of writing on 23rd November), with hundreds of thousands unable to escape the onslaught as hospitals and refugee camps are targeted by air strikes, leading

many people, globally, to question the morality of Israel’s actions. In order to attempt to understand the current situation better, some historical context is vital. The history of the region is complex, rooted in the history of colonialism. In 1947, during Britain's exit from what was known as Historic Palestine, the newly-formed United Nations was put in charge of what the country would become. They decided to split the land into a Jewish State and Arab State. The idea of the two religions living in harmony, however, didn't last long. In the summer of 1947, Zionist forces from the Jewish State expelled Palestinians south into what is now known as the Gaza Strip and contained Palestinians east of Jerusalem forming the West Bank. This created millions of migrants, many of whom were forced to emigrate to neighbouring countries: Egypt, Syria, Iraq and Jordan. This caused an outbreak of conflict in 1948 resulting in Egypt taking control of the Gaza Strip and Jordan the West Bank. The occupation of these areas was contested by Israel but didn't change until 1967, when Israel launched a full-scale attack on Egypt, Jordan and Syria, capturing the West Bank, Gaza Strip and Golan Heights. Israel started its consolidation of control over Gaza quickly by establishing border crossing points and controlling the flow of goods into and out of Gaza, Palestinians were able to move between Gaza strip and the West Bank. From 1967, Israel began colonising Palestine by at first removing its connection to the world and secondly by placing Israeli settlements into Gaza. They founded an agricultural industry to cater for Israel and the West Bank demands, taking advantage of the low salaries for the inhabitants of the Gaza strip. The control Israel was exhibiting in Gaza led to the foundation of a prominent charity called Mujama Al-Islamiya, part-sponsored by the Israeli government; they provided schools, mosques, hospitals and food for the people of Gaza. However, on 10th December, 1987, Israeli troops caused a traffic accident, killing 4 Palestinians. This spark inflamed what was already a tense atmosphere, after twenty years of Israeli occupation, and helped lead to what became known as The First Intifada, which resulted in the killing of 1,024 Palestinians and 118 Israelis. One consequence of this was the formation

of Hamas, from the Mujama Al-Islamiya group, a militant organisation intent on returning Gaza to the nation of Palestine. The Oslo Peace Accords, the formal treaty between Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Opposition (PLO), gave the PLO control in Gaza and The West Bank forming a system of government with elected representatives in these zones. It also promised a plan to independence from Israel over the next 5 years. However, Hamas disagreed with these clauses and voiced their opposition to the treaties. A year after the Oslo Peace Accords were signed the Israeli Prime Minister called for the construction of a fence around Gaza, which was shortly destroyed in The Second Intifada. Israel broke the agreement drawn up after the second Intifada, which caused more unrest and was a significant factor in Hamas winning the popular vote in Gazan political elections in 2006, as Hamas opposed the status quo that so many Gazans had been forced to live with. With the rise of Hamas, Israel closed Gaza off from the world completely placing it under a blockade which lasts to this day.

Israel has continued its campaign of attrition against Hamas for the past 16 years catching the people of Palestine in the middle of the conflict. Israel controls all the points into and out of the Gaza strip, particularly through the Erez Crossing in the North of the district. This means that they dictate when Palestinians are receiving essentials such as food, water, medical aid and electricity, and when they don’t. In 2011 Israel calculated the calories required to live for each person in Gaza, only allowing the minimum amount of food to enter the strip for people to survive. Journalist Yousef Aljamal said, ‘Palestinians are slowly starving.’ highlighting the effectiveness of Israel’s blocks, a form of collective punishment against a community which does not support the people who govern them. The effect of the 16-year blockade has made 78% of water undrinkable; 62% of the population need food assistance and there are 11-hour power cuts per day.

Israel went further following the 7th October attack by calling a formal siege of Gaza with Yoav Gallant, Israeli Defence Minister, saying ‘We are putting a complete siege on Gaza. No food, no electricity, no water, no gas. It is all closed.” Israel shows a complete disregard for basic human rights when it comes to Gaza and this has been highlighted by organisations such as Amnesty International. Israel’s attempt to slowly starve and demoralise the people of Gaza, has so far has failed as a method to move them.

However, the locked resources are not the only way Israel has retaliated against the existence of Hamas. There has been increasing military presence over Gaza with more drones being launched, which Israeli government spokespeople have argued are there to ‘safeguard’ the people who live in Gaza. These new drones continue to strike targets in Gaza and continue to perform observation over the closed airspace. Recently, the Israeli military have deployed drone gunboats to watch over the seas around Gaza ensuring nothing goes in without proper clearance, whilst protecting the vast oil reserves that sit off the coast of Gaza. Israel continues to extract resources from an ever-starved population whilst constricting their population more with every month that passes. The Israeli Defence Force (IDF) doesn't stop at controlling features; they continue to bomb Palestinian land, particularly following the 7th October attack when they struck a refugee camp. This action has been labelled as a war crime by a range of international institutions, Amnesty International and United Nations. Some nations, such as Bolivia, have condemned such actions, and there have been hundreds of thousands of people involved in protests across the globe, taking to the streets, including thousands of protesters in Israel itself.

Israel is not alone in its fight against Hamas. Alongside it stand over 84 countries, from the United States to India, all providing political support as well as further air cover around Israel’s borders. In reaction to the 7th October attack, the United States, along with