7 minute read

Learn More About

Learn More About: Prevention and Diversion

BY JUDITH TACKETT

The national affordable housing crisis is also very visible in Nashville. One could argue that due to the economic success and the growth of our city, we’re one of the locations where the creation of more luxury apartments and hospitality beds, especially short-term rentals, have resulted in the loss of too many previously affordable apartment complexes to the detriment of our poorer population. In short, housing has become tight, which makes finding housing for people experiencing homelessness that much harder.

People working to address homelessness have always spoken about the need to work on prevention efforts. But, until a few years ago, it’s been hard to determine where homelessness prevention starts and ends. The reason is because homelessness is a symptom of other systems that are failing the poor. That’s where we talk about “feeder systems” including foster care, criminal justice, lack of mental health care, lack of insurance, the income gap, etc. The problem seems so overwhelming that conversations start up and fade away as quickly as they began.

But, in the last few years, homelessness experts started to home in on what prevention for the homelessness system means.

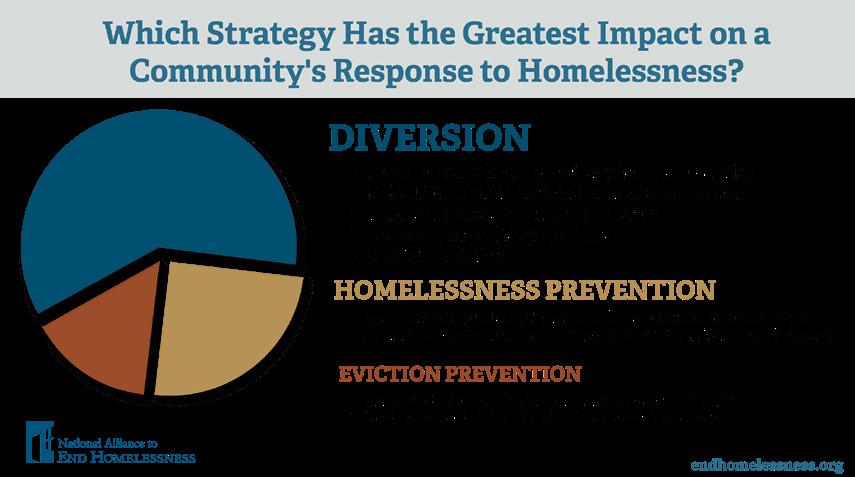

There are three distinct terms that emerged out of the prevention conversation:

• Diversion;

• Homelessness Prevention; and

• Eviction Prevention.

Of those three, diversion is probably the hardest to define. The National Alliance to End Homelessness (endhomelessness.org) explains diversion as “assisting people who have lost their housing avoid entering shelter or unsheltered homelessness by helping them identify alternative places to stay.”

Such alternative places depend on a person’s own connections and most likely include staying with family or friends, moving quickly to a more affordable housing situation, or remaining temporarily at the current location a little longer until another housing opportunity can be found. Diversion happens when people are calling nonprofits asking for a shelter bed. At that point, trained frontline staff should be brought on the line to explore what resources people still have to help them avoid going to the shelter. The next step then is to work with people where they are and help them find another housing option circumventing the homelessness system (shelter or streets) altogether. Homelessness Prevention helps people who are at high-risk of home-lessness and face an imminent housing loss stay housed. Similar to diversion, this can include staying in the same housing situation or moving to a new housing option. But unlike diversion, the hope is to stabilize the housing crisis in a place where the person can remain long-term. In other words, if rent assistance can prevent a family or individual from remaining in their housing permanently, then let’s do that.

Eviction prevention, on the other hand, does not always lead to homelessness. It keeps people housed, but homelessness experts at conferences and in webinars stress that homelessness dollars should not be used to prevent evictions because it is not certain that the person/family would end up homeless even after an eviction.

Who should we target with homelessness prevention and diversion?

The U.S. Department of Housing and Development (HUD), has defined what it means to be “at risk of homelessness” (see box) and depending on the situation, local agencies are left to determine how to assist households best to avoid homelessness.

The National Alliance to End Homelessness provides a neat little cheat sheet that I’ve been using to explain what resources to use for which intervention:

• Diversion: Use designated homelessness funding streams to target it to people who have lost their housing and are about to enter an emergency shelter or sleep outside.

• Homelessness Prevention: Use mainstream program funding such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), food assistance, health care, and other funding streams to alleviate poverty, and/or homelessness funding that is designated specifically for prevention to serve people who are extremely vulnerable and about to lose their housing (a general rule is that their income is at or below 30% of the local Area Median Income (AMI) and they are 14-21 days away from losing their housing).

• Eviction Prevention: Use designated government housing funds (example: Emergency Rental Assistance during COVID) and/or legal assistance (through Legal Aid) to help prevent evictions.

At present, our local homelessness crisis response system is not focusing on diversion and prevention just yet with the exception of a special diversion program for youth and young adults ages 18-24. That diversion program came about through a federal Youth Homelessness Demonstration Program (YHDP) grant that Oasis Center is currently administering. But Nashville is in talks about how to integrate diversion and homelessness prevention in its coordinated entry process.

Why is this so important? Other communities that have increased their focus on diversion have seen huge cost savings. Studies in Connecticut have shown diversion programs cost on average between $1,000 and $1,750 per household depending on the location. This is a fraction of the potential cost that can add up once households become homeless.

Cincinnati found that the average cost per person in their homeless service system was $3,700 in 2021. Diversion reduced that cost to about $1,550, a 58 percent reduction in cost per person. This could free up significant dollars, especially since some areas have seen success with diversion for up to 40 percent of the households that asked for emergency shelter.

I applaud the city of Nashville, which is trying to figure out how to best invest more in diversion and homelessness prevention. I have also proposed that because the city is currently focusing all its resources on encampments, it should partner with a nonprofit to co-lead the diversion and prevention effort. In any case, the investments will be well worth it. As we all know, the longer people experience homelessness the bigger the cost to people and to the systems that try to help.

How HUD Defines At Risk of Homelessness

(1) An individual or family who:

(i) Has an annual income below 30 percent of median family income for the area, as determined by HUD;

(ii) Does not have sufficient resources or support networks, e.g., family, friends, faith-based or other social networks, immediately available to prevent them from moving to an emergency shelter or another place described in paragraph (1) of the “Homeless” definition in this section; and

(iii) Meets one of the following conditions:

(A) Has moved because of economic reasons two or more times during the 60 days immediately preceding the application for homelessness prevention assistance;

(B) Is living in the home of another because of economic hardship;

(C) Has been notified in writing that their right to occupy their current housing or living situation will be terminated within 21 days of the date of application for assistance;

(D) Lives in a hotel or motel and the cost of the hotel or motel stay is not paid by charitable organizations or by federal, State, or local government programs for low-income individuals;

(E) Lives in a single-room occupancy or efficiency apartment unit in which there reside more than two persons, or lives in a larger housing unit in which there reside more than 1.5 people per room, as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau;

(F) Is exiting a publicly funded institution, or system of care (such as a health-care facility, a mental health facility, foster care or other youth facility, or correction program or institution); or

(G) Otherwise lives in housing that has characteristics associated with instability and an increased risk of homelessness, as identified in the recipient's approved consolidated plan;

(2) A child or youth who does not qualify as “homeless” under this section, but qualifies as “homeless” under section 387(3) of the Runaway and Homeless Youth Act (42 U.S.C. 5732a(3)), section 637(11) of the Head Start Act (42 U.S.C. 9832(11)), section 41403(6) of the Violence Against Women Act of 1994 (42 U.S.C. 14043e-2(6)), section 330(h)(5)(A) of the Public Health Service Act (42 U.S.C. 254b(h)(5)(A)), section 3(m) of the Food and Nutrition Act of 2008 (7 U.S.C. 2012(m)), or section 17(b)(15) of the Child Nutrition Act of 1966 (42 U.S.C. 1786(b)(15)); or

(3) A child or youth who does not qualify as “homeless” under this section, but qualifies as “homeless” under section 725(2) of the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act (42 U.S.C. 11434a(2)), and the parent(s) or guardian(s) of that child or youth if living with her or him.