33 minute read

THE ANA presents

from THE ANA: Issue #12

by The Ana

ISSUE #12

Spring 2023

Summer is on the horizon as The Ana heads into the second half of her third year.

It still feels surreal publishing all the beautiful art and necessary writing that have filled the pages of our last eleven issues.

Although, at times, it was not easy. From ensuring we have enough funds to print our yearbooks and hitting deadlines so the artists and writers could witness their work navigate the world and finding places to host our electric events, here we are on the eve of releasing the 2023 Yearbook with no signs of slowing down.

As we continue to gain ground, I want to take this opportunity to remind everyone about the understanding and empathy we all generously gave each other during the pandemic. As things return to whatever normalcy there was before the pandemic, please continue to spread patience and care throughout your communities and to those who may need it. Just because there isn't a global pandemic doesn’t mean we stopped needing time to organize and process the events in the world and our personal lives.

Also, as we head into our fourth year (!!!!), I want to take this opportunity to meditate about “gaining ground.” What does it mean to gain ground? Are we taking space away from others to carve out our space in the world? Obviously, I do not think this to be true, but rather we are gaining the ground lost in our voices and expression collected in our issues and events. Gaining ground for us here at The Ana is about reclamation, not capturing something that is not ours.

See, as I prepare to graduate from the MFA program at SF State, I am determined to understand my footing on this earth and where I stand in the different groups and communities, I am a part of. Where do I go after this? It is a question I ask myself constantly. It brings me stress, panic, and fear. It sweeps the floor beneath me until I am curled up in my bed, wishing that the world could just stop for a second so I can have one clear thought without the weight of doubt on my shoulders.

I am not here to answer how to get out of this headspace, but rather reiterate how much The Ana means to me and express how much I hope it means to you.

In my times of weakness and doubt, The Ana becomes a map of lives and experiences that remind me of the humanity nestled inside the chest of each of us. It reminds me of where I have been, what I have survived, and what I cherish. The Ana has become a lifesaver for me, and I hope it does the same for you, the reader, and you, the artist and writer, because we all need each other on this old ground, we are reclaiming together.

A space beyond the text.

A space where we can celebrate the work put into the craft and understanding our positionality in the literary space.

Carlos Quinteros III Managing Editor & Poetry Editor

Cross Genre Literature

65 Andres Had Always Wanted a Dog by Daniel Gonzalez FICTION

1 Wrecked Remnants by Robert Pettus

39 What Would Khadijah Do? by Akasha Neely

50 I Love You Also, I Promise by Sophia Quinto

76 Fucked in the Name of Empire; or, Death to Fucking America by Akasha Neely

Nonfiction

24 in the poet’s house, i am the mirror by Erick Sánez

90 To The Hardware in My Leg by Lujan Al-Saleh

Poetry

23 Deac by Elisha Taylor

37 On Turning 17 by Alexandria Wyckoff

49 February by Abigail Oak

64 On TV There Are Two Women Kissing by Elodie Townsend

94 Vandals by Elodie Townsend

97 shell by Kwame Daniels

98 Aspen Vista Blue Pt. 1 by Jesse Strohauer

Visual Art

36 Words on Fire by Karen Gomez

38 The Condor’s Cove by Violet Bea

63 Smoke Break by Violet Bea

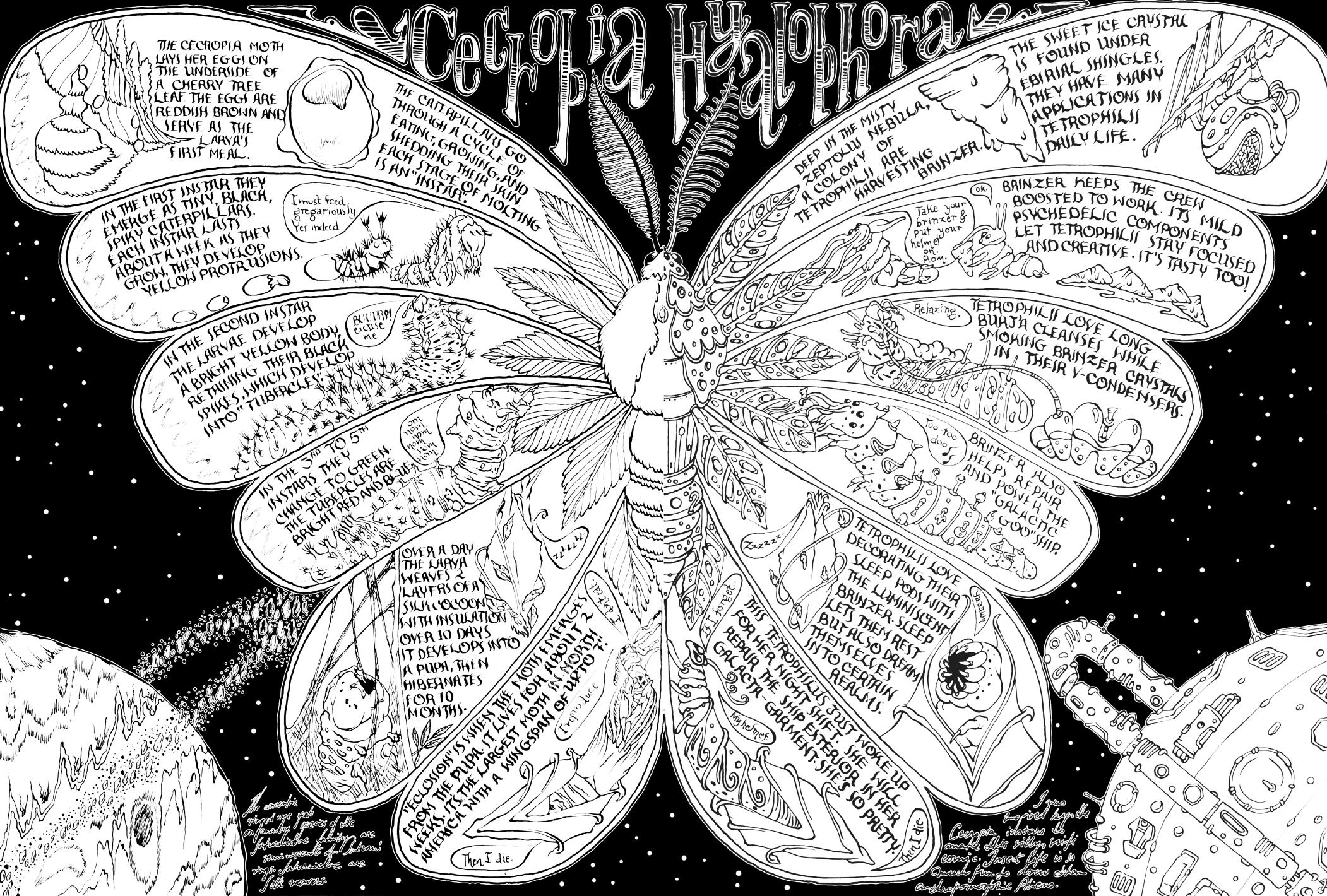

75 Cecropia Hyalophora by Violet Bea

88 T.P.T. by Brielle Villanueva

89 El sol y la hierba by Brielle Villanueva

96 MetaCarpal by Violet Bea

99 What A Joy To Be Beloved by Jesse Strohauer . . . . . .

10 The Serious Business of Childhood a conversation with Christine Ferrouge

100 Writing Through the Mutant Continuum a book review of Poetechnics: Designs from the New World by Yaxkin Melchy

104 Contributors

Wrecked Remnants

fiction by Robert Pettus

The outside world was unknown to her, but she could see a glimpse of it through the window in his room. She had never seen much of anything out there—it was like staring at a slightly mobile painting, one that changed only slightly each day—but she continued to peer into the curved glass of the scope anyway.

“You need to stop wasting your time doing that,” said Mr. Greenwell, rocking on his wobbly stool, “Anything happens up there, you’ll know about it. I promise you that. You won’t be able to avoid it. This little bunker of ours, it’s only holding on by a thread. I’m surprised we’re still here, to tell you the truth—a decade is a hell of a long time to survive in this sort of situation.”

“What else am I supposed to do?” said Alice, turning from the exteriortelescope and glaring backward at Mr. Greenwell, who sat comfortably on his stool, which was cushioned with an old, cut-out Styrofoam mattress-pad duct taped onto its brittle wooden surface.

She grinned at him. He smiled back. He was her only real friend in the world, and she was likely his. Though he was so apathetic—that was a new word she had learned when reading in the library last week; apathetic—he just sat on his stool pointlessly all day, every day.

Mr. Greenwell took a healthy smack from his vape, exhaling the fragrant vapors as smoke engulfed the small room.

“This place is a cell,” growled Mr. Greenwell, scratching at the remnant, prickly gray hairs on his shiny bald head.

“You say that every day. And you really need to quit smoking. I don’t know how the guards haven’t snagged that thing from you yet.”

“It doesn’t even have any nicotine. I make the juice myself—what can they say about it? I’m doing nobody no harm. Plus, they should simply be happy I don’t lose my damn mind at not having a single cigar for ten years.”

“I’m sure your lungs don’t appreciate it,” said Alice, “And plus, since you make it yourself, why don’t you make it a little less…pungent?”

Pungent was another word Alice had recently discovered.

“I like the smell,” said Mr. Greenwell. “Anyway, what are you reading this week?”

“Notes From Underground. Saw it in the library; it seemed fitting.”

“Fitting, indeed,” said Mr. Greenwell, scratching at the creases on his wrinkly brow.

“Why are you so dried up and flaky?” said Alice

“I have psoriasis. No ointment in the hospital wing. They say the patrollers look for it when they go out—I put in a damned request, for that and cigars—but they haven’t found anything. I don’t think they even look. Bastards.”

“Oh,” said Alice. She didn’t know what psoriasis was; she hadn’t learned that word yet. She made a mental note to uncover its meaning. She would ask Mr. Greenwell, but she didn’t like seeming uneducated; that was the paradox of self-education for the proud: questions were a double-edged sword.

Alice felt proud that she so easily recalled the word paradox, though.

Unable to intelligently respond, Alice instead looked back into the exteriortelescope. Exterior-telescopes—one of the only novel ideas of subterranean, post-End life, were tubes, stretching upward through the earth, which used a series of underground mirrors to see into the outside world—like a window. A window from underground into the “real” world. Alice stared at them incessantly, and she mostly used Mr. Greenwell’s, being that he was the only person she really trusted. Every morning, Alice would hop off her top-bunk in the adolescent dormitory and, after stopping by the library to gather her new books, run over to Mr. Greenwell’s room to see what was going on in the real world. Nothing much was happening today. She had seen a tumbleweed roll across the chalky dirt of the outside post-apocalyptic desert, bouncing into an unaware desert cottontail, which leapt around in instinctive, prey-like horror before realizing it was just a dry plant. The rabbit then began eating the tumbleweed, satisfied with the crunchy snack.

“Damn!” said Alice, removing herself from the lens, “As much as I love rabbits, I need some more excitement on the tube!” Encircling her left eye was a red ring, proof of the time and effort she expended staring into the scope.

“You should watch your language,” said Mr. Greenwell.

“You cuss all the time,” said Alice.

“Yeah, but I’m old, so I’m allowed to say whatever the hell I want. You’ re a young girl, so it’s not polite.”

“No one gives a shit about that kind of stuff anymore; we’re at the end of the world, in case you hadn’t noticed.”

Mr. Greenwell chuckled. Alice smiled at him.

“So, what’s for lunch today?” said Alice.

“Let’s see,” said Mr. Greenwell, removing the weekly news bulletin from the organizer on his wall and scanning it for the menu. “Looks like Salisbury steak with brown gravy, buttered peas, and mashed potatoes.”

“We have that every week,” said Alice.

“Peas are easy to preserve; Salisbury steak and mashed potatoes are easy to fake. It’s a pragmatic meal when you live underground.”

“Well I’m tired of it!” yelled Alice, throwing her hands skyward. She was also wondering about the meaning of the word pragmatic.

“I kind of like it, honestly,” said Mr. Greenwell.

Alice smiled in concession, “I do too—I can’t deny it. There’s something about that mushy steak that just gets me.”

Talking about food had worked up their appetites, so they decided to head out a little early for lunch. Alice grabbed Mr. Greenwell’s cane—an old, twisty thing with a rubber base—and helped him from his stool. They left the quiet of Mr. Greenwell’ s room and entered a surprisingly bustling hallway. . . . . . .

“The hell is going on today?” said Alice glancing back and forth at groups of people scurrying by frantically.

“Who knows,” said Mr. Greenwell, “Maybe they’re having a surprise Keno drawing; they’ve done that before. If so, we’re going to have to wait on lunch so I can get in on the action.

The administration had recently begun using Keno as a sort of lottery to help create a bit of excitement and tradition for colony residents. It was a normal Keno game, but instead of money, the winners received additional access to goods like food, pillows, blankets, books, and board games. It had thus far been very successful.

“Maybe you’ll win!” said Alice, who wasn’t yet old enough to participate, “Then you can snag that Connect Four game the patrollers found! Wouldn’t that be awesome?”

“If I happen to win,” said Mr. Greenwell, “I’ll gladly purchase you the copy of Connect Four.” The two of them continued toward the cafeteria. As they pushed forward down the narrow hallway, they noticed in the expressions of passersby more terror and confusion than excitement.

“I don’t think this is related to Keno,” said Mr. Greenwell.

“Yeah. These people are acting crazy,” said Alice, “What do you reckon is going on?”

Mr. Greenwell didn’t respond, but Alice could tell by his worried expression— which crinkled the lines on his wrinkly forehead—that he was nervous about something.

“Let’s go to the cafeteria,” he said, “Somebody will be able to tell us what’s going on there.”

The cafeteria was nearly vacant. Steaming trays of food sat unattended at the buffet. Mr. Greenwell noticed someone—a plastic-apron, hairnet wearing member of the kitchen staff—ducking from the main room of the cafeteria into the back room of the kitchen.

“Hey!” said Mr. Greenwell, pacing over to catch up with her. His cane wobbled with each step as he leaned into it and pushed forward. “Hello, ma’am! I need some help!” Alice, grabbing a hardtack biscuit from a nearby basket, followed him into the kitchen.

“I can’t help you, sir,” said the kitchen staff employee, worry induced sweats painting her leathery face.

“You don’t know anything?” said Mr. Greenwell, “Nothing at all?”

“Only thing I know is what my boss told me, which was not to plan on coming back to work anytime soon. Something serious is about to happen; I don’t know what the hell it is, though.”

Straining to bite into the crunchy biscuit, Alice bit off a chunk of the bread, chewing it aggressively. “A mystery!” she said, nudging Mr. Greenwell in his side, “We’ll get to the bottom of this, won’t we! Finally, some real excitement for a change. This will be way better than staring at radiated rabbits in the exterior-telescope all day.

“Let’s get out of here.” said Mr. Greenwell.

“That’s a good idea,” said the kitchen staff, “I’m about to do the same, myself. Feel free to help yourself to some food.” She handed him a couple of reusable plastic to-go containers.

Mr. Greenwell turned and walked out of the kitchen, making to leave the cafeteria entirely. Alice, noticing he hadn’t grabbed any food, snatched one of the to-go containers from him.

“So, you’re just going to allow us to have this conversation about how we secretly love Salisbury steak the whole way here, and then not even get any of it? What kind of bull shit is that Mr. G?”

“Oh, sorry,” said Mr. Greenwell, glancing toward the hallway, which by this point had calmed substantially, “I had something else on my mind. Let’ s scoop up some steak for the road. And watch the language; we’re in public!”

“Way ahead of you!” said Alice, darting back over to the buffet and filling the to-go container with steak and biscuits.

Their lunch collected, they returned to Mr. Greenwell’ s room.

Mr. Greenwell sat atop his stool at his small desk, his hand at his face—his thumb on his chin and his pointer finger curled around his nose—as was his habit when he was thinking hard about something. Alice, having already devoured her lunch, was now back to staring into the exterior-telescope.

“Man!” she said, her eye still pressed to the scope, “I really wanted that ConnectFour game, you know? I was really looked forward to whipping your old ass!”

Alice heard nothing in response. Normally, she knew, a vulgar comment like that would have elicited from Mr. G at least a snicker. But there was nothing. She tore herself away from the telescope, looking over to Mr. Greenwell, who still sat soberly on his stool.

“We might need to get out of here,” he said.

“How in the hell could we possibly do that? And where would we even go?”

“I don’t know, and… I don’t know…”

“Isn’t there a big door? A big metal, twisty thing that opens into the outside?”

“Yeah, there is. That’s past the administrative offices, though. I don’t see how we could get by there.”

“We’ll sneak it! There are some advantages to being seen as a helpless little girl by everyone, you know. Maybe I can trick them; allow us some time to get by.”

“And what would we do once we got outside?”

“Huh?” Alice was momentarily confused. She scraped her foot across the collected dust of the floor before understanding, “Oh!” she said, “Because of the radiation!”

“Yes,” said Mr. Greenwell.

Alice hadn’t ever been out of the colony. Not really, at least—not since she was two years old, when her parents had dropped her off here.

“Don’t they have suits?” she said.

“They don’t give those to just anyone.”

“Well, obviously we’re going to have to steal them. Sometimes thieving is necessary.”

Mr. Greenwell looked to the floor, considering this wisdom given to him by a child. “Okay,” he said, “We can try it. But first, we have to…”

The walls of Mr. Greenwell’s room abruptly split and cracked. The floor shook. Loud crashes and bangs were heard from neighboring rooms. Mr. Greenwell’s twinsized bet rattled around on the floor before being flung sideways halfway across the room. Alice covered herself with her arms to shield herself from the oncoming blow of the metal bed, but it didn’t quite make it to her.

“It’s happening,” said Mr. Greenwell, “It’s actually happening. I always knew it would, but I guess I became too complacent down here, all this time—during this monotonous decade.”

Alice darted to the exterior-telescope, looking intently and then immediately pulling away in shock before diving back and peering again. After a time, she removed herself from the device:

“Holy shit!” she said, “We have to get the hell out of here—like now!”

“Why? What’s going on out there?”

“Lights, flashes… Dead stuff. Snakes and scorpions. I didn’t see any rabbits—I hope they’re safe—but I did see lots of smoke and fire. The ground is destroyed. There are some sort of drones digging into the sand. The ground is cracked, as if the colony is being uprooted.”

“That’s what’s happening,” said Mr. Greenwell.

“What?” said Alice.

“The colony is being uprooted.”

“What? I wasn’t serious about that; I don’t think so, at least… How could that happen?”

“That’s one of the alleged weapons our political leader’s enemy could use against us. We use it against them, too—supposedly—over in their colonies; over in Siberia; over in the caves of the Caucasus.”

“We’re just sitting under a bunch of shifting sand! We’ll be easy to dig up, right?”

“Probably. I guess it makes sense that the Mojave colonies were among the first hit—assuming we actually were among the first. We must have been… But we’ve been down here for so long...”

“They’re going to dig us up?”

“Yes.”

Dueling buckets of a flying excavator—its metal arms attached to a drone hovering overhead—crashed into Mr. Greenwell’s ceiling, subsequently scooping out and gutting the majority of his room. One of the buckets nearly scooped up Alice, though she managed to spin out of the way unharmed.

“Holy shit!” she said, crawling backward away from the drone. Her back against the door, she twisted it open and fell backward into the hallway. Following her, Mr. Greenwell lifted her up. In the hallway they saw panic. No one knew what to do. Everyone was darting around like feeder minnows trapped in a fish tank as the net delivering their doom moved around the aquarium.

“We have to get to the administrative offices!” said Alice, tugging at Mr. Greenwell’s red checkered button-up shirt to hurry him down the hallway, “We have to make it to the exit.”

“Right,” said Mr. Greenwell, beginning to move down the hallway as quickly as was possible with his cane.

Abruptly, the front end of a bulldozer drone pushed through what had previously been Mr. Greenwell’s doorway. The drone then hovered upward, among the furthering wreckage, and reached out its excavator arms as if to entrap Mr. Greenwell in a pincer. There was nothing he could do about it; he felt the pinch of the sharp metal as it broke the skin of his abdomen. Alice shrieked in startled terror. Mr. Greenwell looked at the drone, which as a result increased the pressure of the pinch. Mr. Greenwell wasn’t aware that drones had been made capable of sadism.

“Go,” grunted Mr. Greenwell, “There’s nothing I can do; I’m toast. Get the hell out of here, kid.”

Looking at Mr. Greenwell one last time, Alice then turned and scrambled down the busy, chaotic traffic of the hallway. Walls crumbled around her; stones from the wreckage fell from the ceiling like pieces in a Connect-Four game. Alice would be lucky to make it to the administrative offices alive, she was well aware of that. She pushed on, nonetheless.

The Serious Business of Childhood

a conversation with Christine Ferrouge

Often times the art that changes us comes into our lives by happenstance. But I was lucky enough to have an artist fall into my life. I met Christine Ferrouge by chance, via email.

She reached out about her upcoming show—Watching/Waiting (April 27 - May 27 at Oakland’s GearBox Gallery) and graciously offered for us to use the space for a reading.

Allow me to digress: the Romans believed that genius was a wind that flowed through people. If you’ve ever sat down to create something you know that electricity. It’s part of the magic of being an artist. But there is also magic in finding people who see you, and you see them.

I felt this way with Christine.

Carlos and I visited her at the GearBox Galley, then took a detour to her studio to view more of her paintings. From the colors she used, the creaminess of the oil paint, to the nuanced explorations of girlhood, I was enamored. It felt like home. Ferrouge’s work and her studio buzzes with tactileness and motion—characteristics that were everpresent in my articulation of girlhood. Girls are fast. They are movers and shakers.

I told Christine that I wanted this interview to be a collaboration. Even though I found kinship in her and her work, I wanted to dig deeper.

I asked her: what question do you want to be asked?

And five days later, at the interview, she answered: I want to be asked about my painting’s connection to art history and contemporary girlhood.

So that’s where we’ll begin.

Christine Ferruouge: My work is deeply rooted in an understanding of art history. Early in school, I discovered the Ashcan Painters, and was inspired by their gritty portrayal of everyday life and I was excited about where American art first became relevant in Western art history. I loved the founder of the Ashcan School, Robert Henri (pronounced: Hen-Rye), who often painted children. I also fell in love with the brushstrokes of Manet, who could create dynamic faces and forms with minimal smudges of paint! I was inspired! I continued to study by looking at the old masters (studying in Florence, Amsterdam, and Madrid).

When my daughters were young, I began thinking about how girls are reflected in pop culture and compared that to history. Their contemporaries had a weird princesses conglomerate that I was skeptical about. When I was young I wanted to be Wonder Woman because she was powerful. And I also grew up with the JonBenét Ramsey story, so as a mother, the dolling-up of young girls struck me as very disturbing.

I don’t know how we ended up with so many cheap polyester princess dresses in our house! I never bought them, but they were everywhere, so I began to paint about them. I realized I was not the first artist to paint princesses, so I looked to Las Meninas by Diego Velázquez, and other portrayals of real-life princesses.

The painting is important for a lot of reasons: Velázquez—the painter, himself—is in the painting; kind of the first selfie of art history. The artist and the audience are both aware of one another and reflected in the painting. On top of that self-awareness—to this day, there are people standing in front of Las Meninas, in the Prado Museum, continuing to be the audience that Velázquez intended. And they’ve been doing so for almost four hundred years!

In contemporary art history, Kehinde Wiley and Kerry James Marshall have always been heroes of mine—for their larger-than-life, dignified figures and art history references. Hung Lu is similarly inspiring to me. My life-size or larger scale is crucial to my work. I want there to be a physical reaction and presence to the characters A six foot man musts to look up at these little girls to witness them.

London Pinkney: I could sit in all this knowledge for hours. I love that we began like this. We have this knowledge, so now I want to ask: who are you?

CF: That’s so existential! (laughs) I always say I am simultaneously a full time artist and full time mom. And my subjects are my girls and girlhood. So I am both raising them and studying them.

LP: I have a kinship with you because, as a writer, I have an inverted experience—I study my mother as she is raising me and, somehow, also raising her inner child. How has your role as a mother influenced your art, and how has being an artist influenced how you parent?

CF: A core part of who I am is being a reflective person, so, in reflecting on what I do as mom, I am shaping that role. And what I do as a mom, shapes the work. It goes around and around. The part that blew my mind when you asked that question is the fact that my girls are also watching me. I realize that it is normal for me to watch them and they understand what the paintings are because that is their life—they know me and what is going on with that work. And they understand art. So they are my best audience, because they understand art history and who I am. It’s us knowing each other, which is incredibly intimate.

As a figurative painter, I have always painted the people that I know, and now the people that I know the best are my three daughters. When I have concerns about them as humans moving through contemporary culture or through girlhood, I use the paintings to work through those feelings.

Much of my work starts as a question. I worry about how they are influenced by their social culture, or how they will survive wildfires and invisible environmental toxins, but I explore it via art, and come out on the other side. In the work I climbed toward hope, and recognized how strong my daughters are, and how adaptable I think about the importance of imagination as play, and how it allows us to create different realities for ourselves that help us define who we are and give us skills to cope with life. So in my work, I’m starting with my girls, but it relates to every person who has ever been a child.

LP: I find it interesting that paintings come out of anxiety, I would think with anxiety, you would want to move away from the stimuli rather than sit in it. Does art work as a coping mechanism of art that allows you to sit in anxiety, or have you always been the kind of person to do so?

CF: Fear is bad. But in a way, I think a lot of good art starts with anxiety because art is a good way to process life. And more importantly, if there are no questions or something to solve, what is the point of making the art? I think there has to be an exploration. My process of painting helps me find answers and usually surprises me with deeper and more universal connections to others than I initially perceived.

LP: How did your daughters become your subject matter?

CF: I knew that I needed to be taking care of myself to be a good mom. And as mom, I didn’t have the freedom to go over to a friend’s house for five hours and have them sit for a portrait for me. So, I started painting the people around me, which were my daughters. Painting my children itself is an act of rebellion, as many women have been criticized and questioned throughout art history—even by feminists—that they should not, or cannot possibly, be both a mother and artist.

LP: You have described that your work is about “the serious business of childhood,” which I love. Children aren’t respected in American culture. They are seen as accessories. And girls are categorically not respected for the cultures they create for one another and amongst themselves. How has this artistic journey revealed new things to you about childhood, and more specifically, girlhood?

CF: I love what you said about girls and how they create cultures for one another and amongst themselves! That is so important!

Often when someone looks at one of my paintings, they relate to it in terms of their own childhood before they think of someone who is currently experiencing childhood. For many years, my daughters and I refer to the person in the painting as “she, her, or that person in that painting”—not actually my daughters’ names. We all understood their likeness was simply a character that could represent anyone. I love the fiction disclaimers at the beginning of novels! It’s so funny to me because it is impossible to not base your inspiration on real people!

I haven’t thought of myself as any of the characters in my paintings until more recently, as my oldest daughter is looking more like a young woman than a child. Also I constantly try to peek into their brains and they are starting to think with more maturity about the world. When they were younger I was clearly the mom looking in at playtime. Even though I related, I didn’t feel like I was painting about myself. It is healthy to not see too much of yourself in your kids. They are separate people.

LP: Do you feel like that healthy separation between these characters and you also mirror the distance a mom should have with her kids?

CF: Yes, And I think it’s helpful. Being both an artist and a mom helps me create healthy boundaries. My children are not my subject to manipulate, and likewise my paintings are their own thing- their own beings. Much like with kids, I make them then they go off into the world. It’s a healthy artist philosophy—if you are overly precious about something- you ruin it. A good artist responds to the needs of the painting and isn’t overly controlling. Similarly, there are things I cannot control in my daughters lives. I do what I can, and then I watch and wait.

LP: What I love about what you do is that your subject matter is living. Yes you are a mother who is an artist and those identities intersect, but to have subject matters that live with you and grow with you feels so ripe with potential. At least right now, the theme of your work is girlhood, but do you see that shifting as your daughters get older? Is womanhood going to be a new theme? Or, as odd as this sounds, are you going to find new children to paint?

CF: Who knows?! I don’t think I’m ever going to stop being fascinated by my girls. But when they grow up and move away, will I have to paint other people again? My girls’ friends and even a few strangers are subjects in some paintings already. Or maybe I’ll have to paint about myself. (Laugh)

That sounds really funny to me. ...All I know is: you have to follow your interest to make good art. And right now my inspiration is my three daughters - and their internal and external worlds.

LP: It feels like the second art project, is you as an artist chasing this subject matter. As if the art is also in making something perpetual. Perpetual girlhood is not a real thing, but it feels like your work captures that in a very noble way.

CF: The things that make us who we are are always part of us- and we form those things during childhood—imagining, inventing, reflection. Those actions are always in us. In my new work I’m growing interested in how girls relate to one another—whether friends or siblings. I remember getting dressed up or ready to go out with girl friends- like for a birthday or a dance. It was a time when you proclaimed who you were to some kind of audience, and it was important. You were becoming. And there was a monumental feeling about it—that it should be documented. That sense of becoming doesn’t go away, no matter how old you get. Becoming is perpetual.

When the girls and I did the photoshoot for the Picnic series, we went out into the desert and set up a picnic with pink-frosted cake and bright blue lemonade. Getting to the location was somewhat dangerous and together we had conceptualized the props and meanings of it all. As we were acting out this strange tea party which I was photographing to paint, I thought to myself, which part is the art? This event?—or the painting I will make in the studio? We are the art and the art is life.

LP: I’m biased, but the artist life is healthy: you have to know your worth, act with intention, know how to create community, set boundaries.

CF: Absolutely. Being in a place where you’re creating is a healthy place to be. There is a universal desire to create, even if you are not in the creative fields—you might be building a company or building a building or building a family. But it’s all creating.

LP: Tell me a little bit about the upcoming exhibit, Watching/Waiting.

CF: The title of the show is about suspense, the sense that something may be about to happen. For me, it is what I do with my girls—I am constantly watching and waiting. My show partner, Joy Ray, makes sculptural weaving that look incredibly fragile. Joy and I found visual connection in the art of falling apart—my paintings kinda look like they’re falling apart, and Joy’s work looks similarly, but neither work actually reaches that place.

She explained to me that her weavings are inspired by a memory of watching people walk on to a semi-frozen lake in Southern California. As the people walked across the lake, cracked and splintered beneath them, so her art captures that precariousness. It is about that tension. And I resonate with that because as a mother watching over my girls, I’m often aware of the ways they or the world around them could fall apart. That goes back to the watching and waiting—that’s all I can do as they move through girlhood. Watching/Waiting runs from April 27th to May 27th at the GearBox Gallery in Oakland!

LP: Yes! Thank you so much for letting us host inside that space. And I’d love to end on some fun, light questions. Since I am a Parliament Funkledelic Fan, I must ask: are you a stoplight, a flashlight, or a neon light?

CF: Ooh! I’m probably a neon light, but in my work I’m using a flashlight. I’m neon, I’m not someone who shies away from attention. I wear a lot of black, but I love color.

LP: And that leads me to the next question: What is your favorite color to work with?

CF: The moment I get to place red on my canvas is always a favorite moment. You have to use it sparingly, and it’s not my favorite color in general, but it brings me back to the pure love of paint. From my earliest memories. I remember dipping my paint brush in dripping red tempera paint at the preschool easels and making that mark on the paper. There’s nothing as exciting as that. Red is a power color—it’s fire, it’s blood, it’s excitement, it’s passion. And you have to use it decisively.

LP: And the final question is: what’s next for you?

CF: After I launch this show, I need to get back into the studio! I’m starting paintings about girls getting ready in mirrors, and about our relationships with one another and ourselves. I’m excited to be in my new LA studio as well, where I’ll be hosting studio visits and enjoying focused work time this summer. Being an artist is a continuous journey.

Thank you so much for this interview. I cherish our conversations. It has been wonderful to work with you. We are thrilled to host The Ana at GearBox Gallery for your upcoming release party!

Three Masked Princesses, oil on canvas, 72” x 48”, 2015 |

April 27 - May 27, 2023

GearBox Gallery in Oakland, CA

To follow Christine Ferrouge: christineferrouge.com

@christineferrouge

Ferrouge’s recent honors include exhibiting in the deYoung Museum Open Exhibit and solo show at Gray Loft Gallery. In addition to studio practices in Oakland and Los Angeles, Ferrouge is a teacher, curator, and promoter of the arts, who contributes passionately to art communities such as: the Oakland Art Murmur, Los Angeles Art Association, and Kipaipai Fellows.

Deac

poetry by Elisha Taylor

I never hear her voice anymore in my name/I just hear the common tree planted firmly by living waters/Swaying my name from first to last and letting his leaves bristle Durrell in the middle/Just as calmly as he could seem/

in the poet’s house, i am the mirror

nonfiction by Erick Sáenz

Con mucho amor a Ángel, Farid, Tato, Vickie, & Roque - ese fin de semana y para siempre

I believe in the power of books. They find you, if you weren’t aware, dear reader. When you’re at your local bookshop browsing dusty shelves for something to jump out at you—that’s the power of books. Other times, it’s a recommendation from a friend / partner / lover. The book connects y ’all in a way that can’t be undone. It’s an anchor for a certain time and place in your life.

And you can always go back; reflect remember.

In the Spring of 2018 I found myself returning to a nostalgic place. My first book had just been published by a press back east and I was invited to join five poets for a weekend of readings in Monterey. So I found myself traversing across those familiar farm landscapes of Central California on the way to the event. Imposter syndrome and that familiar nervous ache in my belly traveled along inside, like the words tattooed on my right arm; taking dreams back at one thousand miles1 down highway 101.

Have you ever noticed all of the different textures books hold?

1. Grab a book off your shelf. Don’t think about which one, try to figure out which will be the most satisfying to touch. It’s better when it’s random.

2. Hold the book between your thumb and index finger.

3. Pause and think about how it feels on your finger tips. What is there and what isn’t?

4. Take your middle finger and brush the book back & forth.

5. Close your eyes.

6. What do you feel? “Forty Four Sunsets” - The Saddest Landscape the attitude, the speech.

Ángel and I met at a reading in Santa Cruz. By that time I had read (and re-read) his debut collection. My book had just been accepted by The OS and I was going through the motions of becoming a published poet and a deep-setting imposter syndrome like a shadow.

Somehow I knew immediately Angel is from Los Angeles; I could feel the traffic, smell the heat radiate off concrete. We’re both adjacent to LA; close enough to know the city but far enough away from the congestion.

We know you gotta hit up the Tommy’s Burgers on Beverly for those late (late) night munchies; but beware the drunks, and those chili cheese fries sitting in your belly for the rest of the weekend.

When I was in my late teens & early twenties I was obsessed with punk music. But more than that, I was obsessed with all the tiny micro-genres of the genre. I found myself devouring information about bands and labels. I’d spend countless hours reading liner notes, noting who played what, documenting labels to look up later, either in real life or on the web. Years later, I find this practice has stuffed my brain with mostly useless information. I see record covers in my mind. I can tell you what band(s) someone played in and how long they existed. Every few weeks I find myself doing a deep-dive on the internet, vastly expanded from those days, and nostalgically downloading obscure EPs long out-of-print. If this obsessive practice did anything for me, it taught me how to throw myself completely into something. To live and breathe this… something.

When Ángel’s debut collection, Black Lavender Milk, came into my life; I was living in Monterey for the third time in 10 years. Let me pause for a second and explain: I earned my BA in English at CSU Monterey Bay, and then promptly moved back from Southern California to earn my Teaching Credential. After that I floated around California spending time in various cities but never feeling home. For me Monterey was (and frankly still is) a place of transition…I return when I need a reset. This time around would turn out to be my last jaunt living in Monterey, although I still visit as frequently as possible.

In the months leading up to my final move to Monterey, I had found my writer’s voice. I’d always had an interest in writing from a very young age, but I’d never made time to focus on my writing or develop a regular practice. Once back I suddenly felt compelled to write about the corridos that kept me up at night, the familiar smells of fresh pan dulce, riding my bicycle and breathing in that salty air, the wind howling in the early mornings, that fog settling on everything outside my window, obscuring the familiar and making things more familiar.

In preparation for the gathering, I read the latest books by all of the poets whom I will soon be kin.

We are strangers, but I feel connected to them through textures. They say the words I could never find in my throat. After the weekend I write a poem for each of them.

I am too embarrassed to ever hit “send”

Everything loops; a snake eating its tail. What’s that called again?

I’m living in Southern California (again) and invited back to Monterey (again).

This time as a guest poet for a Latinx Creative Writing class Ángel is teaching at the college. I’ m nervous but quickly put at ease by the students’ enthusiasm for my book. Rather than go through the passages I had pre-marked in my own worn & creased copy, I let the students curate my reading. They excitedly shouting out the pages of their favorite poems. I comply, reading on a whim.

Ángel and I laugh about this impromptu poem-on-demand over beers afterwards.

The last night of the Latinx Symposium feels like a baptism. The imposter syndrome is gone. I do not know if it will return once I’m back to my real life in Southern California. But I feel different.

Later, we drink, we laugh about the weekend, we watch music videos, cry in each other’ s arms. We scream at the ocean, the pitch black night.

My hands hold fire I better put it to2 su voz como el viento llenando esos espacios vacios, tantos años después

I find myself at the ocean. Every time I return like the punchline to a bad joke no one is telling. It’s because he is there; we ebb & flow through a conversation that is only for us. He was never great at listening, but now listens patiently at the voice that I found after he was long gone.

I say all those unsaid things I couldn’t while I watched him dying. Maybe the point is he can ’t really talk back.

“My hands hold fire” - Sinaloa (is a state) taking it all in: i think we stopped for burgers, one last night together.

The same weekend I visit Angel’s class, I’m asked to give a writing workshop at the local Boys and Girls Club in a sleepy Monterey suburb. I stop at the ocean; for advice, or to calm my nerves. The pavement is wet from a recent downpour, that smell mixing with the Eucalyptus-lined pathway. I read some pages from the book and then tear out a page and film it saturated with saltwater, and then tumbling away with the waves. Not my last communication, but a good ending anyways.

The workshop goes well; I break through with one kid in particular whose story is similar to mine. He knows paternal loss.

We are kin.

We all hop into a rented van the second day, heading to Salinas. Where the first day felt … “academic,” this feels more ________. Farid and I stay together in one of the college apartments I know well. We drink until the wee hours of the AM, and the coffee feels good in my throat and stomach. Ángel is behind the wheel, looking the part of a tired parent taking their kids to a practice of some sort. The day consists of a writing workshop with youth from the area, and a reading that includes local poets.

I am taking it all in.

In the poet’s house, i am the mirror.

Tato reading their poems the 2nd day in Salinas - seated on the floor; confident, relaxed. Moderating a writing workshop with Roque - the young people sharing their stories while we listened, intently. Driving Farid to the tiny Monterey airport; early and hung over. Vicki reading her poems the 1st day in Monterey - the ease in which she spoke Spanish. Crying on the balcony with Ángel, darkness carrying it away.

Several years later I’m eating chicken wings and drinking beer with friends. It’s been a while, although we live in the same neighborhood, and it’s nice catching up. One of them says something like the art world tends to fetishize poetry. The line bores into my head for several days and then finally I remember why I agree with the statement.

The last excursion we take as a (what do you call a group a poets?) is to BAMPFA for a reading Ángel is asked to do. The crowd is very… white… for lack of a better word, a stark contrast to the people we’ve surrounded ourselves with all weekend. We get there early, and find ourselves in the awkward moments of milling around looking at the art and paying way too much for snacks. Finally they are ready to begin.

Ángel absolutely kills it. Their mix of performance and poetry is something I am always envious of. I’ve been privy to many iterations but this one is probably my favorite. As they read to their ancestral peoples, a rope is woven in and out of the crowd. People seem embarrassed by the fact that the script has been flipped: they perform too. No safety in the spectator.

By the end everyone seems to have missed the point. They are unsure how to react once the performance is done, standing idle while Ángel collects their artifacts.

The other reader reads and a sense of familiarity with the work (or the person) fills the room.

A strange way to end.

Later, a cenote surrounding White-washed space bodies pose, then goodbyes.

We hug outside BAMPFA; damp Berkeley air.

Two need to leave to catch flights, head back to their version of home.

I’ve sat down and tried to write about this countless times, words never quite right.

I think about the famous scene in Stephen King’s 1986 film Stand by Me.The main character finally is alone with his thoughts while his friends sleep nearby. He sits quietly and watches a deer approach and linger for that one extra second before vanishing back into the background. He returns to his friends but never tells them about what he witnessed. The memory his own.

The point, I think, is that the main character has this great moment of clarity that he doesn’t need anyone else to justify.

And maybe that’s why I’ve been reluctant to share.

I keep these moments in my heart, return to them when I need to remember what it is to be a poet.

I hope you find these moments, too.

Someone remembers to document the final moments of the weekend.

We’re all there.

Words on Fire, Karen Gomez