16 minute read

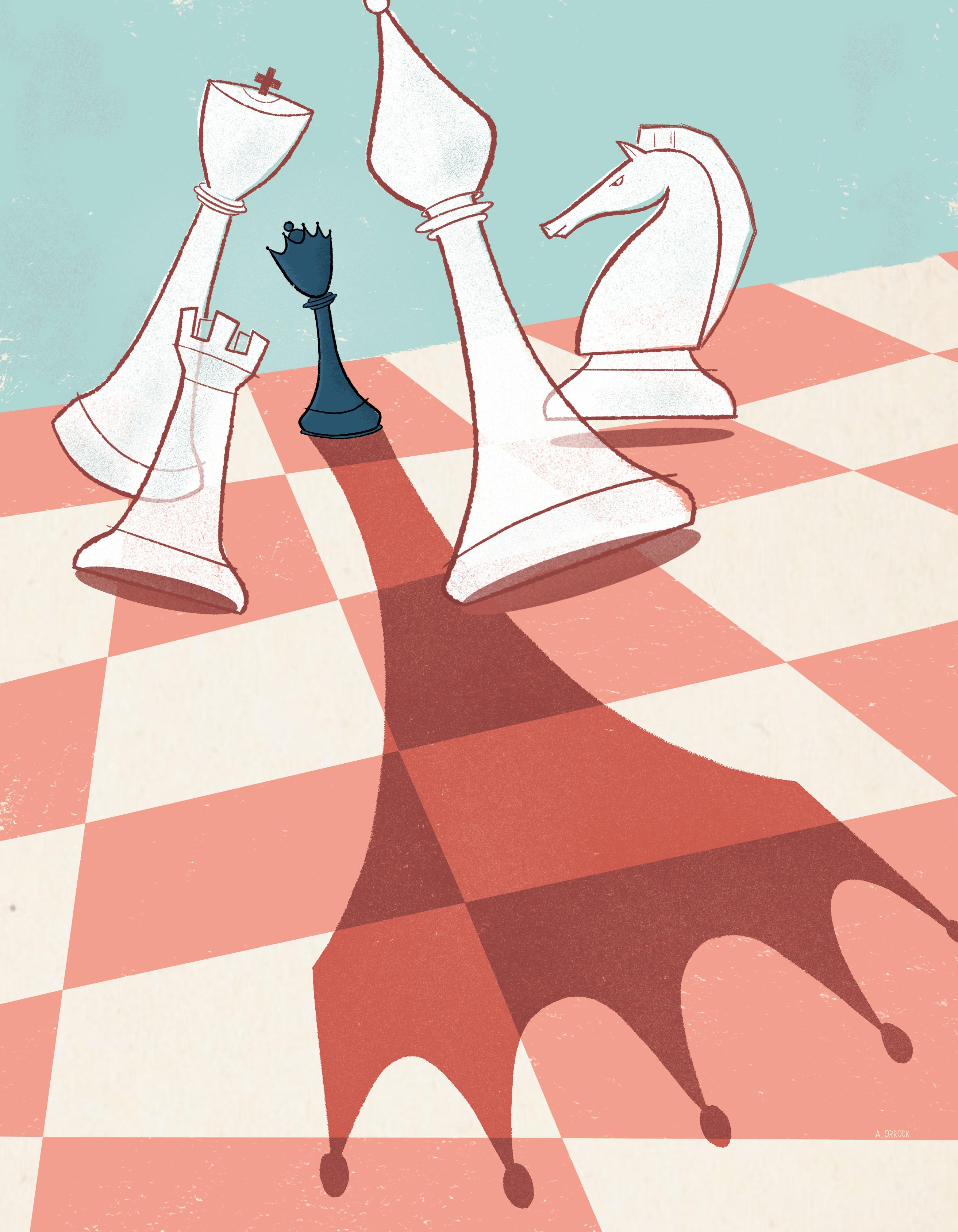

Breaking the Checkered Ceiling

Unveiling the Rich History of Women in Chess: From Pioneering Players to Archer's Chess Team, Explore the Triumphs, Challenges, and the Ongoing Quest for Equality on the Checkered Battlefield

By Amanda Ryvkin | Illustrations by Anika Orrock

With the ability to fly across the board with ease, the queen reigns supreme in chess. Towering over pawns, rooks, knights, and bishops, she is the master of her checkered domain and can move as many spaces as she wants in almost any direction. In a world of black and white and rigid, pre-prescribed movement, she has a level of flexibility and fluidity that is unmatched. Meanwhile, the king, whose safety makes or breaks the game, can only move one space at a time. While safeguarding the king might be the goal of chess, the expert maneuvers of the queen are key to a player’s success.

While the queen may reign supreme on the board, according to Daniel Lucas, the Senior Director of Strategic Communication for the U.S. Chess Federation, as of February 21, 2024, only 11.7% of all U.S. Chess Federation have self-identified as female. In the history of chess, few women have broken through into the highest ranks of the game. Why is it that women have been sidelined in this mental sport?

Surprisingly, the queen has not always been such a significant player in chess. It was not until a real queen who exercised considerable influence came into play that her eponymous piece gained the ability to move more freely.

Chess is largely considered to be a descendant of the 7th-century Indian war game Chaturanga, where each piece corresponds to a role within the Indian army. This iteration of the game didn’t have a queen; it split the pieces into four different types: infantry, elephantry, cavalry, and chariots. After 600 CE, chaturanga evolved into shatranj, which was played across South Asia, regions of Central Asia, and more, and introduced the piece of the “firzan” (in Persian), or counselor. The counselor, the predecessor to today’s queen, was limited to one-space diagonal plays.

By way of the Middle East and North Africa, eventually, the game spread to Europe where, in the 990s, the counselor was finally upgraded to “Regina,” a queen. However, the newly designated “queen” was still confined to the counselor’s extremely limited movements. It wasn’t until the late 1400s that the queen was set free, gaining the ability to move farther and in more directions. What led to this liberation and empowerment? Chess historians believe that this shift was due to the notoriety of Queen Isabella I of Castile.

Queen Isabella I ruled Castile and Aragon with her husband, Ferdinand II, in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. Among other moves, they united Spain, sent Christopher Columbus on the voyage that led to his exploration of the Americas, and launched the bloody Spanish Inquisition which mandated that everyone in Spain be Roman Catholic and led to the exiling and killing of large numbers of Muslims and Jews. Isabella and Ferdinand’s large impact on European politics seems to be reflected in the evolution of chess.

With such a forceful inspiration for changes in gameplay and the emergence of a powerful “female” piece, you wouldn’t be wrong in thinking that women played a prominent role in the world of chess. However, the rise of the chess queen coincided with enforced gender segregation in the game. Now that the queen was the most powerful piece on the board, it was ironic that women began to be shut out of chess. “Chess became a much faster, more exciting game and, thus, came to be perceived as a more masculine pursuit,” notes the Encyclopedia Brittanica. From the 15th century until the mid-19th century, female players were segregated from male players.

The professional and amateur chess world largely revolves around rankings in national and international competitions. This general structure and system began to develop in the 19th century when the first chess clubs were started and the concept of international chess competitions came to the fore. Women were shut out of the nascent chess clubs, but they established their first dedicated club in the Netherlands in 1847, and later, in the mid-1880s, they were allowed to join men at a club for the first time in Turin, Italy.

World Chess Championships began in the late 19th century. The first unofficial world champion match was in 1866, between two internationally prominent chess players, Wilhelm Steinitz and Karl Ernst Adolf Anderssen, with Steinitz emerging victorious. From then on, the winner, the World Champion, would set the terms for future potential challengers and would have to defend their title in arranged matches that they set up. The first official World Chess Championship was in 1886, when Steinitz beat Johannes Zukertort. Women were absent from these competitions, but in 1927, the Fédération Internationale des Échecs (FIDE, or International Chess Federation) established the Women’s World Chess Championship. Later, by the 1940s, FIDE also took over administration of the open World Chess Championship, which remained closed to women until 1986. FIDE has remained the organizer of both sets of championships to this day.

Despite the fact that women were sidelined for so long, the history of international chess features some incredible female players who often gave male players a run for their money in the face of prejudice and misogyny. Soviet-born Vera Menchik won the first Women’s Chess Championship in 1927 and competed frequently against men. According to former U.S. Champion Jennifer Shahade, cited in a New York Times article, Menchik was known for her “fearless, confident style.” Georgian Nona Gaprindashvili was the first woman to be named an International Grandmaster in the 1970s, a title separate from and with higher ranking requirements than the International Woman Grandmaster. According to NPR, Gaprindashvili was known for her “aggressive” play and once even played a game in which she and the other party agreed to a draw only after there were almost no more pieces on the board. Gaprindashvili also played against men and found that, according to her lawyer Alexander Rufus-Isaacs, men “would go to great lengths to avoid the embarrassment they saw as being beaten by a woman.”

Three of the most prominent women in chess to date emerged in the 1990s: Susan, Zsófia, and Judit Polgár. Zsófia reached the rank of Woman Grandmaster and Susan and Judit both achieved Grandmaster status. When Judit became a Grandmaster, she was the youngest person to ever do so in the history of chess. These women fought to open up the chess world to women. Indeed, a 2018 Sports Illustrated article notes that it was Susan Polgár who petitioned that “Men’s” be removed from the “World Chess Championship” competition’s name, effectively creating space for women to potentially compete. Her sister, Judit, eventually became the first woman to compete in a World Championship tournament in 2005, which served as a qualifier to the official World Championship title match. Even Judit, who reached the top echelons of chess only about twenty years ago, was faced with sexism and mistreatment, noting in a 2020 New York Times article that “there were opponents who refused to shake hands.” Since then, no other woman has competed in a World Chess Championship. Unfortunately, Judit did not move on to secure the champion title in 2005, so there has yet to be a female World Chess Champion.

So far, it seems women are still being outranked by men in chess. In 2020, only 37 women were counted among the 1,700 regular grandmasters worldwide. As of January 26, 2024, there are more men named Vladimir (two Vladimirs!) ranking in the top 100 international chess players than there are women. In fact, there are no women listed at all.

Of course, as Coach Jay Stallings, Archer’s Chess team Coach, noted, the “history of women in chess is not as long…because they hadn’t been invited to the table, so to speak, until the 20th century.”

Archer Chess team member Elyse H. ’29 feels the impact of the lack of women and girls in the chess world. “I notice for a fact that when I’m going to a co-ed tournament, [...] it’ll normally be me, [one of her friends on the chess team], and maybe like seven other girls and a room full of boys” across age groups. Archer Chess team Captain Liora G. ’24 also noted that a lot of girls aren’t joining chess because it’s so male-dominated. “Especially for younger girls, they don’t want to be in a room full of guys that won’t listen to them.”

Female players are, to this day, being restrained by bias. A 2023 study published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology titled “Checking Gender Bias: Parents and Mentors Perceive Less Chess Potential in Girls” noted that “parents and mentors thought that female youth players’ highest potential chess ratings were on average lower than male players’” and that this bias “was exacerbated among parents and mentors who believed that success in chess requires brilliance.”

Female players are also being held back by societal expectations. To win at chess, there is a conception that you have to be aggressive and confident, and often, these are qualities that are stereotypically attributed to boys and men. In contrast, women and girls are historically seen as demure. Women have also been socialized to be more hesitant and compliant, to couch their requests with timid language—“If you don’t mind…” Along those lines, they are much more likely than men to not apply for a job because they don’t meet all of the qualifications.

At a recent girls’ chess tournament, Liora G. ’24 noted that the tournament organizers were handing out cooking mitts. This, obviously, wasn’t received very well. Not only is this sexist, but it also feels extremely dated. Who is expecting high school girls to want cooking mitts in this day and age? As she put it, this incident sparked a conversation for Liora and her team about “different unintentional, well-meaning, but still sexist practices” that happen at tournaments. Even in these spaces dedicated to women, according to Liora, “almost none” of the tournament directors for the all-girls tournament were female. Chess culture seems to tell women in chess that they are not as important. Maya H. ’27 notes that she thinks “women are taken less seriously in chess.”

At the top of the chess world, just as in the sports world at large, there are also financial disparities. For example, the 2023 US Junior Chess Championship, which is open to all genders, awards $40k, but the 2023 US Girls’ Junior Chess Championship only awards up to $20.6k. While the existence of an open and a girls’ tournament in theory creates double opportunities for young women to potentially earn prizes, it does seem somewhat telling that the prize amount significantly decreases when the tournament is only open to girls. Furthermore, since girls and women are still working to break into the higher ranks of open chess, these sorts of disparities can unfortunately effectively result in girls and women earning smaller prizes.

However, chess tournaments and public perceptions around chess are evolving, and its player base can evolve with it.

Even within the last decade, the chess world has experienced several seismic shifts. With people stuck at home during the COVID-19 pandemic, the overall popularity of chess increased. According to The Washington Post, after the pandemic began, Chess.com’s average daily user count went from 1.5 million to 5-7 million.

2020’s “The Queen’s Gambit,” the Netflix original series that followed the fictional Beth Harmon’s climb in the chess world, compounded this effect and catapulted chess—and specifically women in chess—into the public eye. The show became Netflix’s most-watched scripted miniseries, with over 62 million households viewing the show within one month. Chess.com’s active users skyrocketed after the show came out. The New York Times noted that from October 2020 to April 2022, Chess.com’s monthly active users went from about 8 million to almost 17 million. Similarly, The New York Times reported that physical chess set sales skyrocketed.

Online chess, in particular, has grown significantly in popularity in recent years. People are playing chess on their computers and on phone apps, and people are even streaming their games. Liora attributes chess streaming as “giving a platform” to many female chess players. “I feel like everything’s had pros and cons, but I feel like it kind of generates publicity but [is] also changing the narrative of chess being like an old man’s game.” These online communities also ostensibly make it easier for female chess players to connect with their peers and feel less “alone in the room,” so to speak. Streaming also helps female chess players find and follow other female chess players.

In a more and more disconnected world, chess organizers like David Heiser of Renaissance Knights believe that chess is creating a way for people to build community in person. “I think things like the chess meetup [are] a way for people to get out and have those personal connections and have something to bond over.”

This has been Liora’s experience. Ever since she began playing chess in middle school, thanks to a random email her mom received in 6th grade from the LA Chess Club, Liora had wanted to be on a chess team—she loved seeing the team dynamics at tournaments. So when she came to Archer, she worked with the administration and Coach Jay Stallings to launch Archer’s inaugural team.

While the subjects of the 2023 Journal of Experimental Psychology study might have shown that gender bias in chess “was exacerbated among parents and mentors who believed that success in chess requires brilliance,” we know at Archer that our students are striking brilliance all the time. Our students have the exact kind of brilliance—and are building the type of community—it takes to reign supreme on the chess board.

In a game known for being solitary, community and social connection—the exact things often lacking in the outside chess world for women and girls—are at the core of the Archer chess experience.

Liora’s favorite part about starting the chess team at Archer is the camaraderie she feels with her teammates. Not only has it provided her with an opportunity to be a leader at Archer and share her love for the game, but she feels that it has also enabled her to “get to know people outside of the classroom” across grades. This experience was echoed by Maya, who remarked that because of the Chess team, she now has a bunch of friends in 10th and 12th grade, “elevat[ing]” her experience at Archer.

The program has grown in the short time it’s been at Archer. In the first year, the team had less than ten people; now, in its third year, they’ve more than doubled their membership. Students come from different chess backgrounds, and Coach Stallings lets students go at their own pace, with each student working in a different place in the curriculum. They practice drills and strive towards different achievements, such as getting checkmate with different configurations. They also engage in different thinking techniques and become familiar with each piece’s strengths and weaknesses.

At Archer, our chess program teaches our students critical thinking and analytical skills. Maya recalled Coach Stallings’ saying: “If you find a good move, think of a better one.” Elyse H. ’29 has taken away the importance of planning ahead and “fighting your hardest.”

Every year, Archer’s Chess team is able to apply these skills and their maneuvers at the All-Girls Tournament in Chicago. These tournaments enable female students to connect and work together to improve. For Liora, one of the benefits of the all-girls tournaments is that, because there are so few girls in chess, most students are not competing in teams. This ends up leading to a more interactive and supportive dynamic. “It’s more collaborative. There’s more talking at the chess board,” Liora shared.

All-girls and all-women titles and tournaments, such as the one our students attend in Chicago, have been a cornerstone of the chess world’s solution to the game’s uneven gender representation. The hope behind these initiatives is that they encourage women and girls to continue in chess and help elevate female players. For example, according to Coach Stallings, before U.S. Chess began recognizing female players in each youth age group, the age group lists were almost entirely made up of boys, and it was discouraging for female players. Now, female players can make a list that feels less outside their reach. In the big leagues, women-specific rankings and tournaments also enable more women to become professional chess players since there are financial prizes and there are more tangible titles.

If Archer is any indication, the future is hopeful for more women on the international chess stage. Heiser, whose Renaissance Knights co-runs the All-Girls Tournament in Chicago, notes that they’ve been seeing increased numbers of girls in chess programs locally as well. Unfortunately, in recent years, growth has stalled a bit. While the pandemic piqued interest in chess for the larger public, it led to a “crash” in the U.S. Chess Federation’s national membership numbers, as stated by Daniel Lucas, the organization’s Senior Director of Strategic Communication. While membership is up again, Lucas noted, “For reasons we don't understand, the number of female members has not fully rebounded.” From 14% of members identifying as female before the pandemic, the number has dropped to 11.7% as of February 21, 2024. That being said, Lucas also shared that identifying one’s “sex” is optional when joining U.S. Chess so “the number is likely somewhat higher.” While this recent dip in female membership levels is unfortunate, the long-term trend is still positive. According to Lucas, back in 2000, only 1% of their membership base identified as female. Even with COVID, that percentage has increased more than elevenfold in just 24 years.

When asked what she liked about chess, Elyse joyfully said, “I love winning.” She knows she’s up against a lot, but she’s prepared for the challenge, sharing, “I do have a lot to prove because I am a girl, and on top of that, I’m also not white…it definitely makes me feel out of place, but also does compel me to perform better… I beat adults. It doesn’t matter who you are.”