6 minute read

“Everything is beautiful if you look at it in the right way”

Edwina Baines

World-famous artist Michael Taylor is putting on his first gallery show outside London for 30 years. The Child Okeford show is a ’must-see’ event, says Edwina Baines, who spoke to Michael about his work

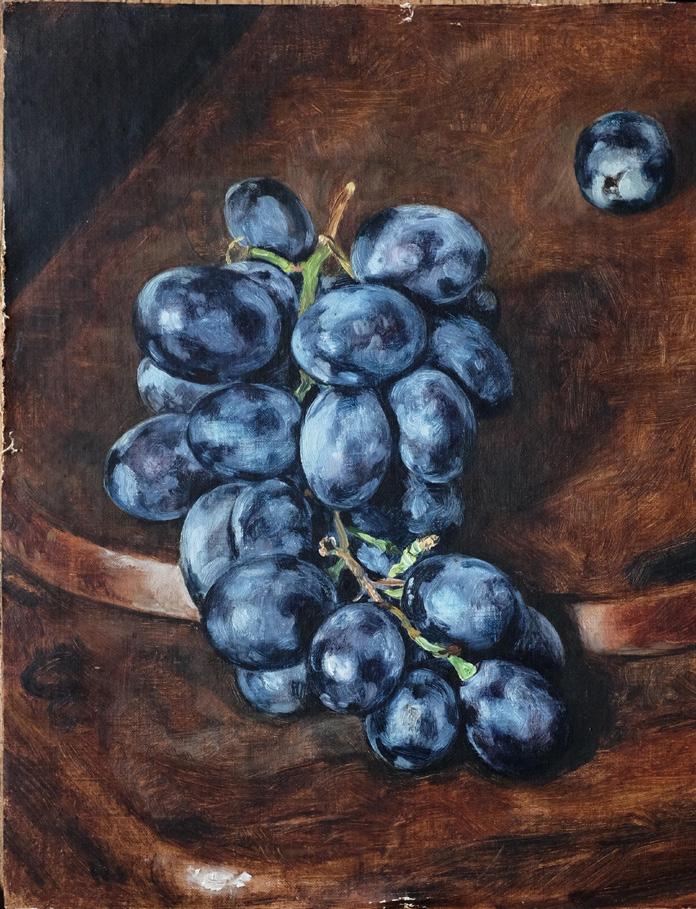

Around forty years ago I bought a small still life painting by Michael Taylor of a bunch of grapes (see image below). I have always admired the talent demonstrated in that oil study, especially the bloom on the grapes - a dark background with the blue-violet bunch occupying a central position. At that time, in 1983, Michael won the National Portrait Gallery John Player Award. This placed him firmly on the map of prestigious portrait painters and led to a commission from the National Portrait Gallery to paint the classical guitarist Julian Bream.

Subsequent commissions followed and the National Portrait Gallery now also owns his portraits of the crime writer P D James (Baroness James of Holland Park), and the composer, Sir John Tavener, along with a self portrait. For his Oscar winning film, ‘The Grand Budapest Hotel’, the film director Wes Anderson also commissioned him to paint ‘Boy with Apple’; the sittings taking place at Hanford School, the Jacobean manor house in Dorset. I was curious to understand the nuances between a portrait and a figure painting.

However, during our conversation at his lovely home near Dorchester, Michael told me he prefers not to be described as a portrait artist: ‘I don’t do so many portrait commissions now.’

Around forty years ago Edwina Baines bought this small still life painting by Michael Taylor.

Attic Stories

In Dorset, there will now be the rare opportunity to view his first Gallery show outside central London for over 30 years: ’Attic Stories’ is to be held at The Art Stable, Child Okeford, Dorset from 5 February - 5 March 2022. The ten stunning works on display are still life and figure paintings - and I was curious to understand the nuances between a portrait and a figure painting. Michael explained ‘They each require a very different approach and technique.’

He likened it to the difference between a novel and a biography. ‘Portrait painting is more like a performance. I’m demanding a lot of the sitter’s time - it’s a two-way thing. You need their attention. I have to engage in conversation. I like to go into their environment if I’m going to paint a portrait because it reflects how they’ve chosen to live. I like to find the sitter’s unique distinguishing qualities which define their individuality.’

There is a rare opportunity to view Michael Taylor’s first Gallery show outside central London for over 30 years: ’Attic Stories’ is to be held at The Art Stable, Child Okeford, Dorset from 5 February - 5 March 2022 Work featured in this photograph: On easel: In parenthesis. Lower left: Copper basket with fruit. Right: Still life with Orchid image: Edwina Baines

‘darting glances of great intensity’

P D James spoke about her experience of sitting for Michael. During a sitting, she asked, ‘Are you trying to make me look grim and mysterious?’ He replied, ‘I’m not trying to make you look anything. I have enough difficulty painting what I see!’ She apparently felt that was the mark of a good portraitist. Painting with deep concentration and giving her ‘darting glances of great intensity’.

There was a certain amazement when she first saw the portrait. She said there was ‘a conviction that this was a portrait beautifully painted. The skill of the painter impressed me tremendously... it had something that can be preserved for posterity. I think it is a face of someone who has looked on the darker side of life, certainly!’ A wonderful tribute.

Michael went on to describe how a figure painting differs from a portrait.

The placement of each figure’s hands seemed particularly expressive in many of the paintings. Always beautifully portrayed.

Michael explained, ‘Hands are very expressive. The odd thing is, if you paint a hand anatomically correctly, it looks wrong. You have to paint how it feels. Often I’ll paint it correctly and then wipe it over with a cloth and what is left is more expressive.’

Portrait of PD James (copyright National Portrait Gallery)

’I’m still learning’

His technique does not include a lot of drawings; rather he completes preparatory diagrams and notes for his own use and then draws on the canvas with under-paint. However, he told me that he has recently been attending life classes again. ‘There is nothing like the rigour and discipline of objective drawing for sharpening up the brain and eye.’

Sitting with Michael in his studio, I was surrounded by the canvases for his exhibition. He is able to take an everyday object such as a sewing machine, a pepper pot or an old oil can and paint it with extreme precision.

The pictures certainly take time to look at, each object gaining significance. There is a tenderness and reverence in his interpretation of both everyday items and the figures themselves: it is no wonder that Michael completes only three or four paintings each year. He is able to ‘commune with an object for weeks and weeks, in complete silence or with a bit of Haydn, getting to know it thoroughly. It’s a meditative process. The only way I can get the necessary focus is to take my time and then do nothing else.’

Michael Taylor in his studio. Works featured are - Left:’Toppled Machine’ Centre: ’Three tiered Table’. Right: ‘Attic Scene with Grave goods’. Michael holding: ‘Petrified clock with oil can’ image - Edwina Baines

A still life is a work of art where the predominant subject matter is that of inanimate objects, either natural or man-made: this genre had its heyday during the Dutch Golden Age of the sixteenth century. Also known by its National Portrait French title, nature morte, the term “still life” derives from the Dutch word stilleven, which literally means motionless or silent life. It is a genre which has fallen out of fashion in recent years - but Michael manages to portray a contemporary twist on the timeless tradition so that even the most mundane objects are imbued with a life beyond the ordinary and can be made into masterpieces.

The Curator of the National Portrait gallery writes of the ‘Sheer beauty, weight and intensity of his ‘still lifes’ - so I can understand that at the end of an intense period of painting, Michael needs to get outside to walk each day in our beautiful Dorset countryside.

https://www.mrtaylor.co.uk