5 minute read

Personal essay: Experiencing “the best of both worlds” and living in the melting pot of the world

MEL LAMM Staff Writer

Growing up, I moved back and forth between Turkey and the United States every two years. My father was in the Air Force and met my mother while he was stationed in Turkey. It was love at first sight, literally. He knew absolutely zero Turkish, and she knew nothing about America. And yet, my dad took it upon himself to bridge the gap, dedicating years to not only learning the Turkish language, but also to educating himself on the country’s history, traditions and the way of its people.

After years of polishing his “Tarzan talk” and building relationships and connections with my mother’s family and friends, they eventually got married. Soon after, my dad got orders from his job to move to California, which led to my mother leaving her home country for the first time. Soon after moving to their new home, I was born.

My mother had started picking up some English, but she was still heavily dependent on pocketbook translators and my dad. She didn’t work the first two years of us living in California, and because I grew up with both of my parents speaking Turkish, it became my mother tongue.

We eventually moved back to Turkey for another two years, and being surrounded by family and a familiar language felt more comfortable. But that quickly changed when I was 5 years old and we moved back to California. The biggest difference from the first time we were in the state was that I had to start preschool. At the time, my dad was stationed in Iraq, and once he got my mom and I settled into our new home and registered into my new school, he had to go back, leaving my mom to teach me English and find herself a job. When I was at a young age and with very little English of my own, my mother managed to use what she knew to get a job at Walmart. Meanwhile, I had a hard time making friends of my own and trying to understand why the letter “C” exists if it makes a “K” and an “S” sound, not a “J” sound like it does in Turkish.

My mom tried to teach me what she could, but since she only knew how to speak English, she didn’t have the ability to teach me grammatical rules or spelling. This led to my dad retiring from the Air Force so he could come back to the United States to teach me English. It was a long and difficult struggle that lasted years, and he would get called into parent-teacher conferences to be told I belong in ESL or other special courses for help. My teachers showed him my assignments where I had mixed up “couch” and “coach,” “soup” and “soap” and various spellings of words with special, non-English characters, such as “ö” or “ü.”

My dad took the time to teach me English, to read and write correctly, and to speak and enunciate my words. I remember at the age of 7, sitting at the dining room table for an hour repeating the “th” sound over and over again until my “dank you” sounded like “thank you.” My dad started only speaking to me in English and encouraged my mom to do the same, which helped both of us in the long run. By the end of third grade, I was speaking English fluently and touching up my reading and writing the best I could for an 8-year-old.

The tables turned when I became fluent in English and my mother was still figuring out how to spell items for grocery lists. She’d come to me for help applying for new jobs, and I would help translate the application questions and explain the job survey scenarios for her to understand. Ultimately, it went beyond translation.

I eventually grew up to adapt to the American way of life, but many things continue to be a struggle for my mom to wrap her head around. For example, she had to adjust to tipping here, since that isn’t the custom in Turkey. Even differences like American home architecture have taken some adjustment. So many houses—especially in the Virginia area—don’t have foyers; it’s common for Turks to have extended welcomes and goodbyes right by the front door where they’ll talk for an additional 15–20 minutes, but many townhouses here are not built to accommodate that.

We moved here to Virginia a week before the start of my junior year at my first American public school. I had no idea what to expect besides what I’d seen in movies and pop culture media, especially the movie “Mean Girls,” which was quite accurate to my personal high school experience and moving to America.

By the age of 18, I had finally gotten my driver’s license in the state of Virginia, and a year later so did my mom. I helped her study for the exams and explained what all the different signs meant. She didn’t pass her first time, but neither did I; driving in Turkey was much different than in the U.S. For instance, kids start driving here at 15 instead of 18, which we both thought was crazy. In Turkey, though you drive on the right side of the road like in the U.S., the right lane is for parking. In fact, if your car fits, it’s a parking spot. I also had to show her how to pump her own gas into the car, since a gas station attendant does it for you in Turkey just like they do in New Jersey.

Today, I am beyond blessed for my bicultural background and truly getting to experience the best of both worlds. Moving to America after being raised overseas has opened my eyes to the different western ideas and perspectives of other people, both good and bad. The conversations I’ve had here have enlightened me and given me different ways of looking at the world. And at times when I felt alone or misunderstood, I also remember I am living in the melting pot of the world. I have made so many positive connections with people who also have similar stories and backgrounds to my own.

I can’t help but think how moments like this have affected my childhood and shaped who I am today. Having to help and guide my mother with things that usually a child needs help with forced me to grow up and mature faster—to learn “adult things” while still figuring out how to be a kid. The struggles of cultural differences and language barriers might have been the biggest obstacles I faced as a young foreigner in a new country, but it was exactly these struggles and obstacles that have shaped me into the person who I am today and understanding both sides of my nationality. Despite all the miscommunication and struggle to understand the English language, my mother and I both managed to learn and guide each other through it all.

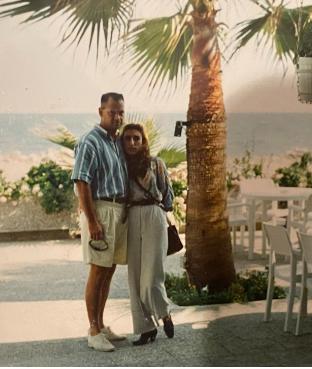

My parents in the ‘90s on their second date, which consisted of a lot of charades, along with ice cream and a nice walk by the beach. The person taking the photo was a Turkish market owner named Cemal (Jem-aal), who spoke English and Turkish and became a good friend of my dads, helping him learn Turkish for my mother. He was there to help translate between them.

Do you skip meals or not buy food in order to pay for gas, rent, utilities or other necessities? If so . .

“Swipe Out Hunger” is for You!

A simple and confidential online application is all it takes to get access to meals at the Top of the CRUC! Meals are loaded directly to your EagleOne Card, so you can swipe in just like all other students with meal plans!

Please don’t go hungry! We have more meals available than are being used, so there are plenty to go around.

Use this QR code to apply, or contact Chris Porter at CJPorter@umw.edu for details.