7 minute read

BURSTING AT THE SEAMS

GPs are being forced to work in cramped premises which hold them back from recruiting staff and meeting patient needs.

Ben Ireland visits three practices which highlight the need for urgent investment

Kensington Road Surgery has outgrown its longstanding home in a Victorian end-terrace house in Coventry.

On the day The Doctor visits, one nurse had been turfed out of her room twice before midday.

‘It not only puts me behind,’ she says. ‘I had to kick one of the doctors out of his room. It was like we were playing musical chairs. We’re very productive, but we could be even more productive if we weren’t faced with this.’

Huma Latif, a GP partner at Kensington Road, says the pressures to keep up with everrising patient demand have taken their toll on the practice’s workforce who she feels deserve to work from a site with sufficient space to do their jobs.

The practice has been innovative with its space but is bursting at the seams. The back of the reception area also serves as a staff kitchen, with a fridge a makeshift table. There is no room to add a lift, so patients in wheelchairs must be seen in ground-floor consulting rooms. The medical secretary works among boxes of gloves and toilet rolls. The only staff room is in the loft with a slanted roof, so anyone over 5ft 4ins can’t stand upright.

Staff take the brunt of the inconvenience so patients don’t have to, but some effects are unavoidable. The midwife has been forced upstairs and on-street parking is not readily available given competition from customers of the nextdoor tyre shop.

Foundation of care

‘Patients have come to expect an excellent service, which we provide,’ says Dr Latif, who joined Kensington Road as a partner in February 2022. ‘I want to ensure we continue to give that, but it’s not sustainable in the current building.’

She adds: ‘We pride ourselves on giving really personal care. That was honed by the partners before me. I saw how hard everyone works, the potential in the practice and how we can build on that – a big part of that is the building.’

Partners welcome the relatively recent development of ‘additional roles’ staff, but Dr Latif says they are ‘constantly playing merry-goround’ for space to work from. As well as three first-contact practitioners and a clinical pharmacist on-site, there is a visiting paramedic, an occupational therapist who mainly does home visits and social prescribers reluctantly based off-site.

With space at such a premium, ‘if an emergency comes up, and we need to do an ECG, we might have to kick someone out of one of the downstairs rooms which immediately puts us behind,’ Dr Latif adds.

‘There’s a knock-on effect to the whole practice; receptionists do an amazing job but if things change or get held up it upsets patients in the waiting room, which can be heard in the consulting rooms.’

Recruitment and retention is ‘an issue’, Dr Latif notes.

‘We need more staff, but there is nowhere for them to work. When locums come in, I ask them what might make them consider a salaried role. The premises always comes up. It’s a major barrier to recruitment. If we had the building, the rooms, we could recruit. It would be so much more appealing. We could take on trainee GPs, or a junior pharmacist, but our existing pharmacist doesn’t even have the room they need.’

Kensington Road’s list has grown by about 2,000 patients over the last 20 years, peaking at nearly 7,000 pre-COVID. But because of how tight services are, this has dropped slightly to about 6,500. Dr Latif says: ‘Patients were getting frustrated they couldn’t get appointments – which comes down to the lack of space.’

‘We can make it sustainable and continue to give that level of care if we have some support for that investment,’ she insists. ‘We need a new practice that’s purpose-built.’

Dr Latif went to the Best Practice exhibition in Birmingham and spoke to banks and architects about possibilities. It gave her plenty of ideas, but a funding ‘minefield’ remains an obstacle.

When NHS improvement grants are offered, a practice’s notional rent will be subject to an abatement depending on how much is funded. So the practice pays long-term. The only other option without involving a third party is self-funding, which usually involves bank loans given the costs involved.

Dr Latif says: ‘There needs to be some clearly earmarked money to support investment in GP premises which is easily signposted so we know where we stand.’

In Dr Latif’s experience, ‘banks seem more amenable to the idea of two practices merging under one roof. But that could get messy, and lead to disagreements. Plus, I believe in old-school general practice. Our patients love that we’re a family practice they can walk to.

‘It can be quite demoralising as a new partner. When you come up against such brick walls it makes you question your attempts to improve the practice and quashes aspirations.’

Daily struggle

Kensington Road is not the only practice in Coventry desperate for investment.

Stoke Aldermoor Medical Centre was purpose-built in

1992, when it had a list size of 500 patients, and extended in 2006. Its three GPs now care for about 6,600 patients.

Partner Parveen Aggarwal says: ‘We’re bursting at the seams. It’s so busy we have people doing admin work on laptops in the kitchen around others who are trying to take a break.

‘Some staff use the practice manager’s office. Staff are essentially hotdesking, but in practice leaving your room to write up your notes somewhere else doesn’t work. And you might need to make confidential phone calls. We’ve run out of shortcuts.’

There are six consulting rooms at Stoke Aldermoor, not enough for the doctors, nurses, pharmacist, physiotherapist and physician associates. Dr Aggarwal is keen to become a training practice but feels that is impossible given the daily battle for rooms. ‘There isn’t enough space,’ he tells The Doctor

Dr Aggarwal paid architects to draw up plans back in 2019, sought council planning approval and developed a business model.

But improvement grant funding has still not been forthcoming. As a last resort, he has considered splitting one consulting room in two, turning the rest area into another and moving that into the loft – giving eight consulting rooms.

He fears going ahead with such temporary measures could make it harder to claim funding long-term.

Such funding was available back in the late 1980s, when Dr Aggarwal received a loan of more than £80,000 as a new GP partner. ‘I was very grateful for that support,’ he recalls. ‘I have so much more expertise behind me now, I know we can provide a good service for today’s challenges with the right support.’

His oven-ready expansion plans – which he sees as the ‘bare minimum’ – would cost £250,000, and Dr Aggarwal is not even asking for all of that, just a contribution. If it came to fruition, he could accommodate two GP trainees and two medical students and allow ARRS (additional roles reimbursement scheme) staff their own rooms.

‘If we compare it to PFI funding, it’s much better value,’ he adds. ‘It’s not a lot to ask. In an ideal world we would have a much bigger expansion so the practice could cope as its list size grows.

‘This is the only GP practice serving a growing population in a deprived area. We have 15-20 patients applying to register every day. I’m going to have to stop taking new patients if I can’t get access to funding. If we want to offer a good service, even a basic service, we need space.’

Provision potential

One Coventry practice where staff feel happy is Broomfield Park, which was the beneficiary last time any practice in Coventry and Warwickshire LMC received estates funding – back in 2016.

The £2m project, completed in 2019, enabled it to grow its list size, including a satellite site at the University of Warwick, from 14,000 in 2016 to 20,500 in 2020.

Broomfield Park houses four partners, five salaried GPs, three to four GP trainees and 12 ARRS staff in a combination of full- and part-time roles. Its modern, airy building has spacious consulting rooms and good accessibility.

Walls in the waiting areas are decorated with intentionally calming floral wallpaper and there are designated admin and meeting rooms.

Monica Green, a partner since 2002, says the results show what can be achieved when GPs are given financial support for their premises.

‘Thankfully, we have room for everyone currently. But we are running out of space. We probably went for more rooms than we needed at the time but wanted to futureproof the practice.’

Need for investment

Doctors at the BMA’s 2022 ARM called for ‘HS2-type investment’ in GP estates as 91 per cent backed a motion calling for extra funding and to look at the limits to disabilityadapted consultation rooms. A rider to the motion, backed by 95 per cent, called for more space for GP trainees.

A BMA report published in December 2022 laid bare the ‘alarming’ condition of healthcare estates and recommended ‘substantial’ capital investment is made available to GP practices and hospitals.

It found 26 per cent of respondents to its survey working in primary care said the building in which they work is in a poor or very poor state and concluded: ‘Shortage of space is a major challenge in general practice, making it harder for GPs to see patients quickly and even preventing some practices from expanding their patient list.’

In 2018, only half of the 1,000 GPs responding to a BMA survey said their practice was fit for present needs – and two in 10 said their practice was fit for future needs.

The NHS Confederation made investment in estates one of the 10 priorities of its Delivery Plan for Recovering

Access to Primary Care, published in March.

Peter Holden, who sits on the BMA GPs committee, and gave evidence about the state of GP estates to the Commons health select committee last year, says: ‘The Government wants us to do more in general practice, the Government wants more GPs, and the Government has provided more people through the ARRS scheme –but they need somewhere to work from, and our buildings are bulging at the seams. One of the reasons patients can’t see a doctor is that there’s nowhere for us to consult from.’

Dr Latif at Kensington Road sees the difference funding could make to her practice and believes the state of general practice sets the tone for patients’ experiences of healthcare.

As she puts it: ‘Politicians talk about general practice as the “front door” to medicine. But if your front door is in tatters, what do you expect for the rest of the service?’

‘If we want to offer a good service, even a basic service, we need space’

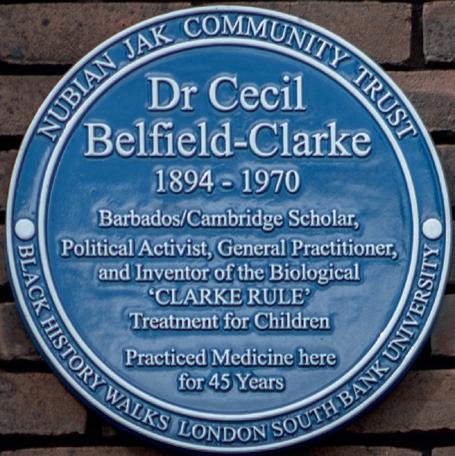

At a time of endemic discrimination, Cecil Belfield Clarke was a black, gay doctor who thrived in mid-century Britain. His civil rights legacy is now being celebrated, as Tim Tonkin reports