9 minute read

Al Finegan

The Charles Eaton

MASSACRE PART 2 By: AL Finegan

Advertisement

Foreword: In researching this story, I found that the deeper I dived into the details of the fate of the passengers and crew of the Charles Eaton after she was wrecked, the more variations of the events emerged. From official records, newspaper articles and personal stories written at that time, I present what I believe to be the story closest to the truth of those unfortunate souls to have been on board Charles Eaton in 1834.

Long before the white man came to Australia, the Torres Strait, situated in the seaway between Cape York Peninsula and Papua New Guinea, was the province of tribes of fierce warriors. Many of their traditional stories have the same epic quality one finds in the Norse sagas. These warriors were the Vikings of the Torres Strait and New Guinea waters. The Murray (Mer) Islanders, at the north head of the Barrier Reef, were among the fiercest raiders of all the head-hunters of all the Islands, and were renowned, even among their savage neighbours, for their warlike propensities. Like the Nordic Vikings, all adult males went to war.

I pick up the story of the passengers and crew of the Charles Eaton after being wrecked, the hulk upright, and half submerged on a coral reef somewhere near Sir Charles Hardy Island, just off Cape York. The treacherous bosun and four of his mates had commandeered the last of the ship’s lifeboats and sailed off, leaving a desperate 26 survivors staring after it until it was seen no more.

Captain Moore gathered the remaining crew and passengers and told them that their only hope of survival was to build a raft from the timbers of Charles Eaton and attempt to sail to an island in the Dutch East Indies. He appointed his first mate, Clare, to select a team and start building. He also ordered his second mate to organise a team to swim below and recover as much food and water as possible from the inundated galley. The D’Oyly family set up a small area on the open deck, and assisted by Ireland, established a small degree of comfort. Each day the crew managed to distil the contents of a cask and some bottles of water from the sea, by the aid of the ship's coppers and a leaden pipe from the quartergalley cistern. Each person was allowed a daily ration of two wine glasses of distilled water, and a few biscuits. Clare and his crew worked all daylight hours, chopping down the masts and tearing up timbers from the deck. After seven days, a raft was completed and tethered to the hulk’s stern. As soon as Clare declared the raft complete, all crew and passengers scrambled to get on board. As more people dropped onto the raft it sank down, and down, until all on board were up to their waists in water. The captain decided that the passengers were his first priority and ordered all crew but two sailors off the raft leaving himself, the surgeon Dr Grant, the D’Oyley family and their nanny, and Mr. Armstrong on board. By dusk, those on the raft had settled in, establishing as much comfort as conditions allowed, securing water and rations as safely as possible, and waited for dawn. As daylight stirred the men on the wreck, Clare went to the stern and saw that the rope by which the raft had been made fast to the hulk had been

BY: Al Finegean

cut, and he and his crew were now alone on the wide sea. He assumed the captain had cut the rope during the night and put his trust in Providence to guide himself and his passengers to some place of safety. Those who were left on the wreck had no choice but to start to build another raft. The vessel's topmasts, lashed together with coir rope was covered with the ship’s doors to make a deck. They also made a sail out of some cloth which had formed part of her cargo. It took another seven days before the raft was completed. Then they set sail, now at the mercy of the wind. No trace of the Charles Eaton wreck has since been found. For several days, and having survived on little food, they passed an island, and saw another one ahead. Suddenly a wave of fear overcame the crew as a canoe was seen paddling towards them. It was a massive construction and contained ten or twelve natives. As they approached, the natives stood up and extended their arms, apparently to show they had no weapons, and were inclined to be friendly. On reaching the raft the crew were startled as the natives leapt on board. To the crew’s surprise the intruders conducted themselves peaceably, and seemed curious about the raft, closely examining the strange white men and their belongings. After a short time, the native in charge indicated by sign language that they should leave the raft and get into the canoe. At first, they hesitated, then with no apparent choice, they boarded the canoe. In less than an hour they were landed on an island which was later identified as Boydong Island. After disembarking, the natives led them about the island in a show of searching for food and water. None was found. On return to the place they had landed, the crew dropped to the ground in despair, so exhausted by fatigue and hunger that they could scarcely walk. Satisfied that the sailors were physically spent, the natives’ attitude changed to one of hostility. Suddenly armed with clubs, they adopted a ferocious bearing and stood around the party grinning and laughing in a most hideous manner. It was obvious that they were revelling in the anticipation of their murderous intent. In this dreadful state of suspense, Mr Clare addressed his companions, recommending them to be resigned to their fate, and read to them several prayers from a book which he had brought with him from the wreck. No sooner had they composed themselves, when the natives attacked. With screams and shouts, the weakened sailors tried to scatter. It was hopeless. One by one the sailors were caught, bashed with clubs until dead. The first killed was Ching, and after him his companion Perry, and then Mr. Mayer, the second officer. Mr Clare, who, in his attempt to make his escape to the canoe, was overtaken by his pursuers, and immediately killed by a blow on the head. Ireland and Sexton, the cabin boys, sat clinging together, trembling in abject terror, awaiting their fate. Ireland later wrote, “A native came to me

with a carving knife to cut my throat, but as he was about to do it, having seized hold of me, I grasped the blade of the knife in my right hand, and held it fast, struggling for my life. The native then threw me down, and, placing his knee on my breast, tried to wrench the knife out of my hand; but I still retained it, although one of my fingers was cut through to the bone. At last, I succeeded in getting uppermost, when I let him go and ran into the sea, and swam out; but being much exhausted, and as the only chance for my life was to return to the shore, I landed again fully expecting to be knocked on the head. The same native then came up with an infuriating gesture and shot me in the right breast with an arrow; and then, in a most unaccountable manner, suddenly became calm, and led, or dragged me a little distance, and offered me some fish and water which I was unable to partake of. Whilst struggling with the native, I observed Sexton, who was held by another, bite a piece of his arm out; but after that knew nothing of him, until I found his life had been spared in a manner similar to my own”.

In his book, Ireland went on,

“At a short distance off, making the most hideous yells, the other savages were dancing round a large fire, before which were placed in a row were the heads of their victims, whilst their decapitated bodies were washing in the surf on the beach, from which they soon disappeared, having been probably washed away by the tide. Sexton and I were then placed in charge of two natives, who covered us with the sail of the canoe, —a sort of mat, —but paid no attention to my wounds, which had been bleeding profusely.”

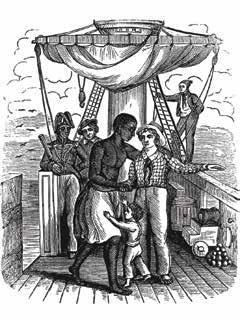

The next day the natives collected all the heads and boarded their canoe, taking Ireland and Sexton with them. They rowed to another island where the native women lived. On landing there, Ireland was surprised to see the two D’Oyly children. A traumatised George D'Oyly told Ireland that the first raft had been intercepted at sea, and that the passengers were brought to this island where they were all murdered, except himself and his brother. George said through his tears that his mother had been struck down when attempting to jump into the sea with little Willy in her arms. Her body was dragged ashore while little Willy was saved by one of the women, who took care of him. Ireland saw a distressed Willy in the woman's arms. He also noted some fancy pieces of the ship's cabin-doors attached as ornaments to the heads of their canoes. They appeared to prize many of the relics they had collected from the rafts. In the centre of the village, a tall hut was decorated with tortoise shells. Attached to these were many human heads in various states of decay. On a pole, in pride of place, the heads of passengers from the first raft swung in the breeze, attached by a coir rope. Ireland was horrified at seeing two that stood out, those of Mrs D'Oyly and Captain Moore that were plainly distinguishable, the former by her hair, the latter by his features. At regular intervals the native women danced before the gruesome display, with aggressive gestures and horrid yells.

Later that day an argument arose among the excited natives as to which of the four boys were to be kept. After much loud shouting and arguing, with natives charging back and forth, Ireland and Willy were dragged aside and handed to a group of women. Teenagers George D’Oyly and John Sexton were hauled to the front of the display hut. Without warning, they died in a hail of spears. A few days later, the only survivors of the Charles Eaton wreck, John Ireland and William D’Oyly, were taken to Darnley Island. Here they were placed in a special hut for exhibition as curiosities while natives from all over Torres Strait were charged a fee to view the strange white children who had come out of the sea. The boys were really a sideshow, and later they were taken on tour, being transported by canoe to other islands in the Strait where they were also exhibited.

As time passed, interest in the lads waned, and they probably would have met the same fate as their shipmates but for Duppar, an elderly chief of Murray Island. Duppar thought he would like to keep the boys as pets. He sailed across to Marsden Island, where the lads were then being exhibited, and after much bargaining, he managed to buy the boys for a bunch of bananas apiece. On Murray Island the lads were treated kindly. John Ireland was christened Wak, and little Willy D’Oyley, who became the spoiled darling of all the native women, was named Uass. The boys began a contented life among the natives.