8 minute read

GREY FOX COLUMN

from The Chap Issue 110

by thechap

Style Column

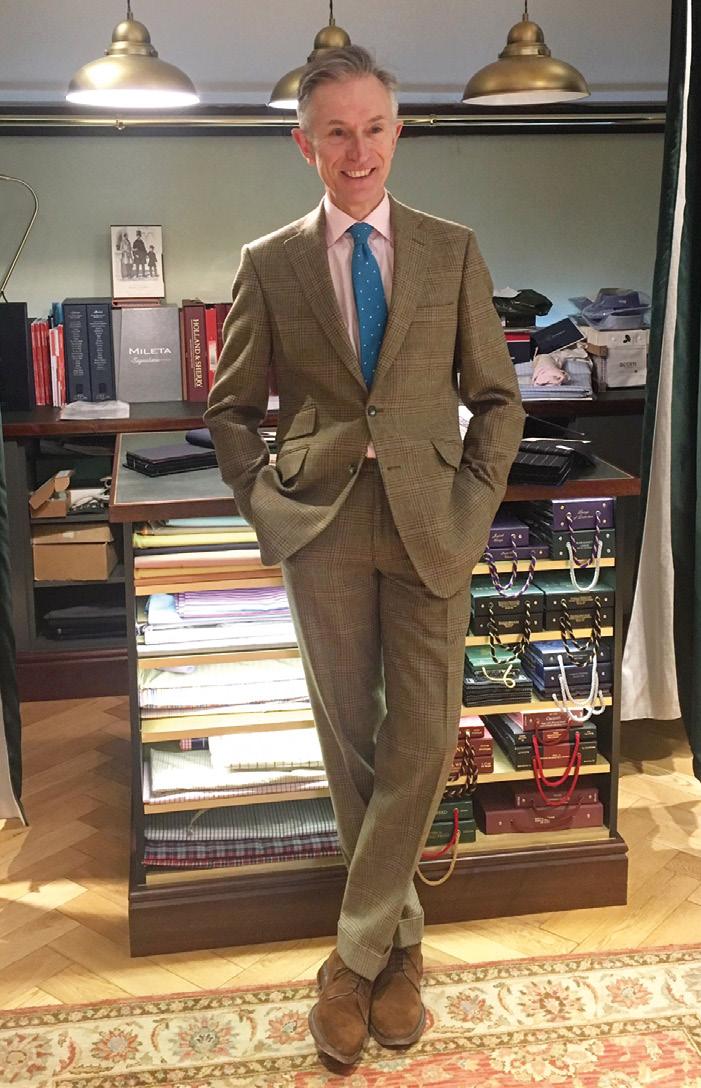

David Evans dusts off his winter woollens and tweeds and visits the Campaign for Wool to find out why wool is the best fabric of all www.greyfoxblog.com

As winter tightens its grip, we turn our attention, naturally, to wool. For millennia this wonderful material has kept sheep and their wild forebears both warm and dry. The pre-domestication origin of the species is lost in the mists of time and may now be extinct, but early animals would have been initially hunted and later domesticated for their meat, milk and skins. Once they were farmed, their fleeces would have been plucked as they moulted or, once an appropriate tool was available, shorn and the wool made into cloth. It would be fascinating to know how man discovered the skills of spinning and weaving to make cloth to replace skins for their clothes. The advantages of using a renewable resource would have been clear – to provide a skin you need to slaughter the animal – wool comes from the fleece which regrows each year.

The Campaign for Wool organises an annual Wool Week at which the virtues of wool are extolled. In Cumbria, the local sheep,

Herdwicks, spend much of their time on the fell in all weathers, developing tough fleeces that keep them warm and dry. Handling a fleece leaves one’s hands greasy with lanolin, which helps the animal shed the heavy Lakeland rains. While Herdwick fleece is often too harsh for clothing (although I have a very stylish Herdwick tweed jacket) it is these weather resistant properties that make wool such an ideal material for our clothes: warm, water resistant and sustainable. The Campaign for Wool describes other properties: it’s a natural insulator, breathable, biodegradable, resilient and elastic, odour resistant and fire resistant (for the pipe smokers among us) and, unlike man-made fibres, it doesn’t shed indestructible microfibres into the environment.

At this year’s Wool Week, the Campaign for Wool collaborated with Hackett to produce their Townhouse Tweed. Launched by Jeremy Hackett (profiled elsewhere in this issue) and the Campaign chair, Nicholas Coleridge, the tweed was developed in collaboration with Lovat Mill. Using a 29-micron Cheviot wool yarn blended with wools from New Zealand and the UK, the yarn is spun, woven and finished in the UK. A perfect wool combination, the New Zealand wool imparts softness to the handle while the British wool adds durability.

The Hackett Townhouse tweed colours were based on the vibrant colours of the rooms at 14, Savile Row. Tweed can be a fascinating

vehicle for colour and this fact was used for the early Scottish estate tweeds, which reflected the colours of each estate’s environment, partly to provide camouflage for those stalking deer or shooting game birds. You can still have your own personal tweed designed by Araminta Campbell in Scotland. I love the idea of an inner city tweed, showing the grime and colour of urban life. Such a cloth is indeed available from Dashing Tweeds, who are in some ways the urban equivalent of Araminta Campbell, whose designs reflect the rivers, stones, heather and vast rain-laden skies of Scotland rather than the hard, grimy surfaces of the urban environment.

In September or October I dig out my knitwear and tweeds and shake them all out in the garden. As a counter-moth measure, I will have cleaned and brushed everything at the end of the winter before putting it into storage for the summer. Sometimes repairs are necessary (climate change has been a licence for moths to promulgate profusely in London) but after a good pressing, tweeds and flannels always look perfect for the chillier months.

London Craft Week has been steadily increasing in size since its inception in 2015. The word ‘craft’ has rather homespun connotations to many, and it’s interesting that a language as rich as ours doesn’t have a vocabulary to describe skills that depend on the human hand, eye and experience and which apply to everything from mechanical engineering to woodcarving. This year’s exhibitors alphabetically covered everything from automotive through candle making, embroidery, leather working and paper making to woodworking. This autumn I was asked to mediate a panel discussion at the new Chelsea Barracks development in London between five premium but very diverse British brands: Edward Green (shoes), Floris (fragrances), Ettinger (leather goods), Bentley Motors and Johnstons of Elgin (cloth, knitwear and clothing), all of which manufacture in the UK. The oldest of these brands dates from the early 18th century and the youngest is nearly 90 years old. The skills of their workers and designers have developed over decades, or even centuries, underlining their international reputations for product quality. In my travels around many British workshops, mills and factories over the last ten years, I’ve noticed that the workers tend to be in middle age and beyond. Of course, this isn’t always the case; in some places it’s been great to see young people learning real and important creative skills. However, British manufacturing needs young people to ensure its future and companies like Bentley Motors, Ettinger and Johnstons of Elgin have invested much in future skills.

Issues such as sustainability and the nature of a quality product were also discussed. British products can be pricier than those made in other parts of the world, where wages and living and working conditions aren’t so high. While British manufacture will never be as it was in the glory years of the previous two centuries, it’s good to see the standing that British goods have as luxury items around the world. Sadly, in the UK itself, many consumers still prefer cheap to quality and show little interest in the high quality products made in the UK. While not everyone has the budget to buy quality goods, many cheaper products remain unworn and are eventually disposed of, going into landfill and wasting money that could be spent on fewer but higher quality items.

I recently acquired a perfect example of British manufacture in the shape of a briefcase from Royal Warrant holder Ettinger. The case is made from bridle leather and arrives with that waxy bloom that protects and nourishes the leather. Beautifully made, cut and stitched, this is a luxury item that will outlast me and, like all the best leathers, its appearance will improve with age – a sure sign of a quality product.

A recent example of the rise of British manufacturing in certain sectors is the launch by Bremont of a collection of watches with movements made at their new watchmaking facility in Henley. British watch and clockmaking was once a world leader (think of Harrison, who invented the marine chronometer in the 18th century, and Smiths Industries, which made

high quality watches and movements in England until the middle of the last century). Reviving any manufacturing heritage of that sort, once lost, is a costly business. It’s taken brothers Nick and Giles Ashley some years to acquire the workforce skills and the expensive specialist machinery required to develop a new proprietary movement, but it has now been completed – the first watch to have been manufactured in any scale in the UK for fifty years. Bremont’s watches have, over the last couple of years, become more attractive visually and their new limited edition Longitude is no exception. It contains a piece of brass from the Flamsteed meridian line of longitude at Greenwich; a bit of a gimmick perhaps, but many of their watches contain bits of old aircraft and other historic artefacts (including a piece of Stephen Hawking’s desk) and I rather like the idea.

While on the topic of British watches, I wanted to mention Fears Watches again. This Bristol-based watchmaker was revived by Nicholas Bowman-Scargill, a descendant of the founder, and recently celebrated its 175th anniversary with the launch of two archiveinspired vintage-style rectangular watches assembled in the UK from overhauled ‘new old stock’ Swiss movements. They are examples of how one man’s dream can create a beautiful, quality product. I met Nicholas recently, who told me that, during the first covid lockdown, he left his business to work stacking shelves at a local supermarket, to avoid having to close the business and lay off his employees. This is a brand worth our support and typifies the many young impressive entrepreneurs that I meet running small British businesses.

My blog reaches its tenth anniversary as you receive this issue. It’s meeting exciting, stylish and creative people like Nicholas Bowman-Scargill that makes me determined to keep the blog going for at least another ten years. Hopefully, like my Ettinger briefcase, it too will improve with age.

Campaign for Wool: oliverbrown.org.uk Hackett: hackett.com Lovat Mill: lovatmill.com Araminta Campbell: aramintacampbell.co.uk Dashing Tweeds: dashingtweeds.co.uk Edward Green: edwardgreen.com Floris: florislondon.com Bentley Motors: bentleymotors.com Ettinger: ettinger.co.uk Bremont Watches: bremont.com Johnstons of Elgin: johnstonsofelgin.com Fears Watches: fearswatches.com n

LONGER FEATURES

Interview: Lindsay Duncan (p82) • Jules Verne (p90) • Around the World in Eight Cocktails (p100) • Cooking (p106) • Travel: Italian Riviera (p110) • Motoring (p119)