CreativeDirector

SocialMedia

Editor-in- Chief

Graphic Design

Angie Menezes

Ariana Turner

Celia Cousineau

Ilan Elenbogen

Juliana Gurevich

Kaiya Scholl

Lillie Ostarello

Mallika Pallipuram

Sahana Raj

Sarah Haddad

Val Garcia

Yasmine Steele

Zoey Fischer

Event Planning & Multimedia

Ananda Sangli

Anthony Gonzalez

Catherine Urquiza

Della Griffin

Dhanai Haderaj

Emma Haugh-Ewald

Estelle Orleans

Esther Phipps

Francesca Dumitrescu

Gracelyn Sensibar

Jenna Glassman

Molly Pfeifer

Natalie Monroe

Salman Khan

Sam Pasquesi

Shagun Varma

Shannon Dwyer

Will Monroe

Aditi Dixit

Anna Pevey

Annika Mandrekar

Caelin Muniz

Farrah Anderson

Holiday Maag

Isabelle Zhao

Julia Di Marco

Katelyn Barbour

Leo Flood

Mika/Nox Burton

Rachel Menke

To point out the obvious: we’ve lost a lot during these past two years. It is easy to feel frustrated, like you’ve never been given a real chance at the “true” college experience. But do not succumb to such a despairing narrative—striving for eternal youth within four (or more) short years is contradictory to what it really means to feel eternally youthful. It is defined by the way you inspire, uplift, and laugh with one another.

However soon you came, however soon you’ll leave, you play a great role in our creative family. I am grateful to see you all continue to express yourselves so freely.

Elle Terrado President (2020-2022)

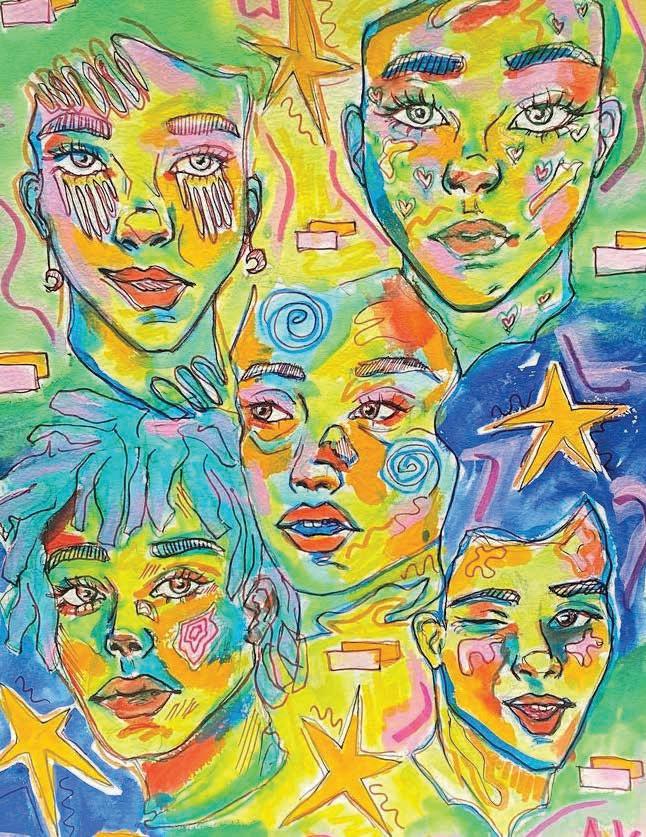

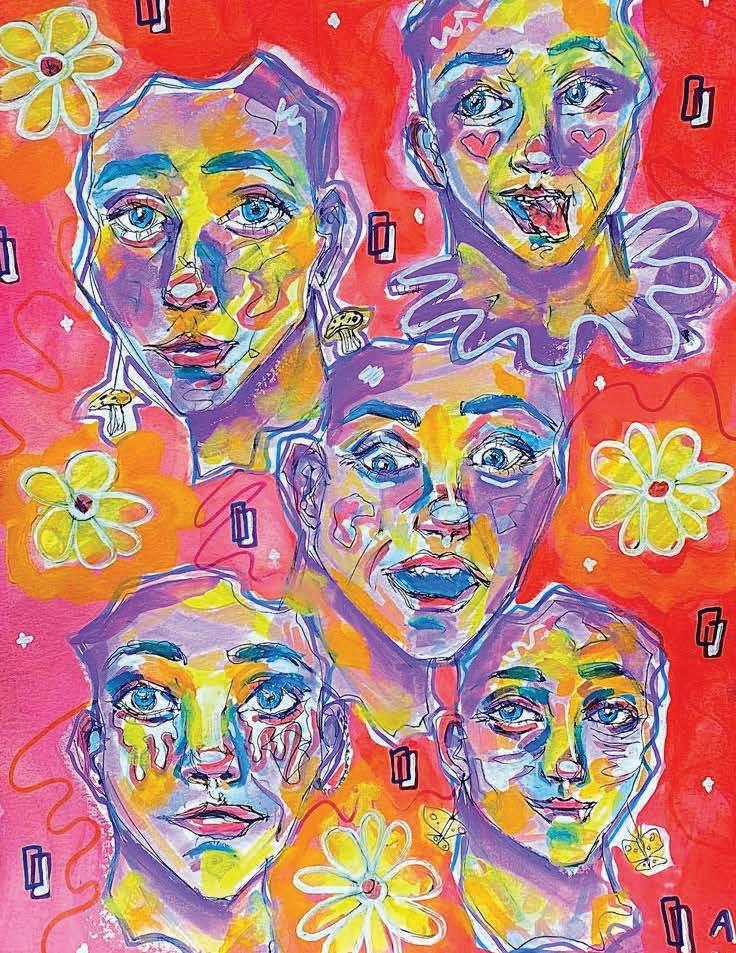

I was looking through your art all morning and it made me want to just light a candle, run a bubble bath, maybe grab a snack… it relaxes me, in a way. How do you feel when you look at your art, and furthermore, how do you imagine it making others feel?

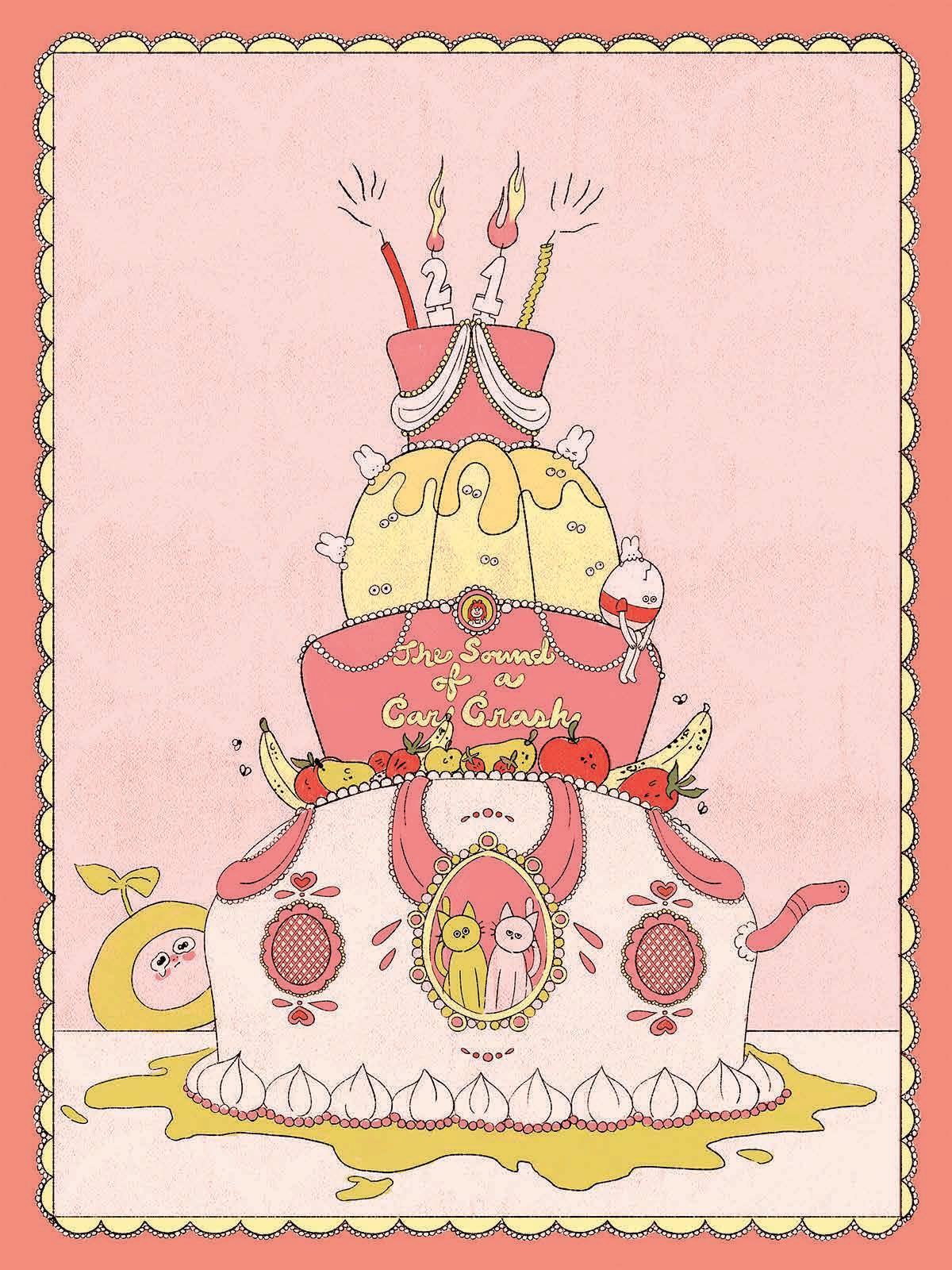

“Yeah. I think that’s sort of subconscious because I’m really attracted to pastels. Greens, pinks, and oranges are my favorite colors, and having this bright, almost sickeningly sweet exterior is what draws a lot of people to my work initially. And it’s fun, when I’m dealing with darker topics, to make them super sweet and saccharine and have that initial layer of comfort, so when you look at it a little longer you’re like, ‘what the fuck is happening?’”

With your comics, I noticed that your character design also plays into that sweetness, but you don’t shy away from vulgarity. I think in one about boba, you had a tapioca pearl calling someone a “dumb bitch” (which I loved). Can you talk more about your comics and the thought process behind those?

“The boba was very much my internal monologue, yelling at myself, like, ‘damn, bitch, you don’t have money, why do you keep spending money on boba?’ I guess that one is about the guilt you feel from simple pleasures that you should just be able to enjoy. We all experience this guilt in this capitalistic society, you know? The things that bring you joy are often demonized because you’re like, ‘oh my god, I need to be working, and not wasting my money on this sweet little boba.’”

The boba was kind of an asshole, though.

“The boba was an asshole, but the boba is me. I’m an asshole to myself sometimes, and I feel like people resonate with that.”

What is your dream piece to create?

“I want to do a graphic novel! My comics are like little vignettes, but they all exist in the same universe. Right now, it’s easier for me to create short stories rather than an extended piece with a cohesive narrative, because that takes more heavy planning. Ideally, I would plan it all out and really build up that universe.”

That sounds like a universe the world needs to see. I hope it happens soon.

“I hope so, too.”

I’m curious about the recurring themes in your work. I have seen a lot of food, and a lot of these playful little animal-like characters. What do they represent to you?

“In terms of the presence of food- food has personally always been a comfort for me. It’s something that makes me feel at home and like myself. I love cooking and eating a good meal with people I care about, but it’s also a symbol of something I need to do to take care of myself. These themes of food are sort of reminders for myself to eat. They’re almost foreboding, even though they’re so cute, saying ‘you need to take care of yourself, you need to eat this meal.’

The little characters, yeah, they’re just little guys. I love making characters with hats because I’m kind of frustrated with being a person a lot of the time.

The hats are usually either a fruit or an animal, and they’re meant to be the character’s way of escaping humanity.”

It’s interesting that you mention food as something that makes you feel at home, because much of the earlier work on your Instagram is focused on a home setting.

“I made most of that work in quarantine, but I’m also just someone who spent the majority of my life in my room. I wasn’t very outgoing until college, and the room is this safe space where you can curate what you want to experience. It’s a way of control, and also a source of comfort, but also a source of imprisonment. That early work was more fun, but at the same time, I felt like I was decaying in my room a little bit.”

A recent piece of yours shows two people fused together, with their heads connected by a cherry stem. It seems that the idea of duality often flows through your work — Does that mean something more to you?

“For the cherry piece, that one was sort of about my relationship with myself, but also growing up with a sister. If you’ve grown up with siblings, specifically if you’ve had a sister, it’s like, your mom always dressed you the same, and I guess a pretty big chunk of your identity is formed around that relationship.

That’s definitely part of it; looking at how I’ve experienced a weird difficulty establishing my own identity because it gets filtered through your sibling. It can be difficult to discern where you end and the other person starts and what is actually true to you.

I luckily have a very close relationship with my sister, though. That problem is definitely something I experienced when I was younger and have outgrown since college.”

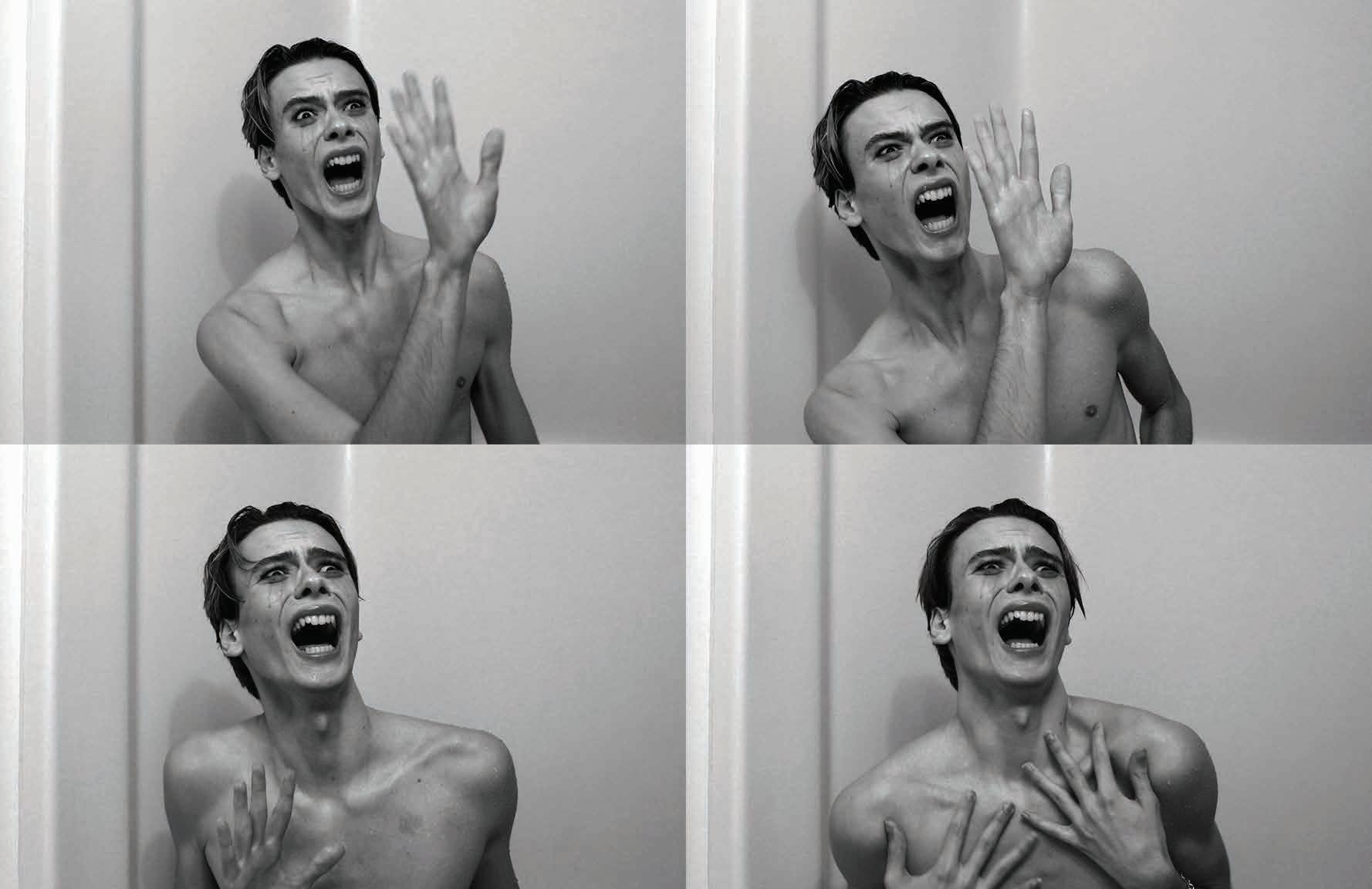

It looks like you’ve shifted from mostly digital work to this new, softly-shaded style of colored pencil drawing. You’ve also dipped into some multimedia stuff, like the print of a “clown bunny” you crocheted. Do you have a favorite medium, or are you just constantly expanding your horizon?

“I still do digital work, but right now I’m in a period where I’m working with traditional mediums. With my digital style, I want it to be all flat, but with colored pencils I have that middle-school urge to render something super dramatically with all of the shading and dimension.

I am first and foremost a ‘drawer.’ Drawing is my home, I love drawing so much. I was a former painting major and thought that was gonna be my life, but then it was like, ‘actually, no, I hate this shit.’

As far as the ‘clown bunny’ goes — wait, I have him. I’ll get him right now. I love these, you know, little guys. I remember in my first-year sculpture class, I told my professor I wanted to make a little guy, and he said, ‘maybe you can make it look like a little guy to you, but not to other people who don’t want to see that.’ But now it’s like, if you don’t wanna see a little guy, you don’t have to look at my work.

I used to be heavily based in realism, and I was straying away from the cute stuff to appease professors, and I think that’s what I thought art was. I’ve been attracted to cute things my whole life, but there is so much sexism surrounding things people deem as feminine or cute. People demean it by seeing cuteness as instantly frivolous and not meaningful. That was a stigma that pushed me away from creating work I actually wanted to create.

I love crocheting these little guys because it feeds my soul. It just does. I still do love realism, but it’s not what serves me right now.”

I also understand that you’re in a band, Soft and Dumb. Is there any struggle balancing your time and creative energy between music and visual art?

“Definitely. I’ve written music since I was around twelve years old, which is something that I kept very private, and I’ve also created art since I was a kid, which I got more academic validation from and felt more comfortable showing off. I remember when I was fifteen, I had this mental breakdown where I was like, ‘I need to choose one.’ But, now, I see both of those art forms as equally worthy of my time. It’s very rewarding to me, and they feed each other. Many of the songs I write deal with similar themes that I address in my work.”

Finally, for the question I’ve been dying to ask — can you share the story behind your Instagram username, “cre.puff”?

“Cre.puff! It’s literally because I saw some cream puffs. I was just talking about this — me and my friends, we kind of speak stupidly together. We say things in a weird way or shorten our words, and we talk like children sometimes. Anyways, I saw cream puffs at 710 Mart, and said, ‘oooh, cre-puff.’ I liked the idea of ‘.puff’ instead of ‘.com’ and just went with it. I don’t even know why it’s my user, but cream puffs are really good. It’s a good user.”

Throughout middle school, I was constantly told that high school would be the “best four years of my life”. But, once high school began, I just heard the same rhetoric about college.

It’s easy to understand the assumption that college would be the most enjoyable period of early adulthood. We are pretty much done growing up—we are not children anymore, but we have, for the most part, yet to enter the “fully grown-up with adult responsibilities like paying bills and filing taxes” era that plagues the rest of our lives. In our early twenties, we finally reach a stage in which we are more comfortable with ourselves than we were in high school, or at the very least, everyone is more open about their struggles with identity.

We have retired the script that tells others how we have every single thing figured out and we love ourselves completely. Most of us are away from our parents and are allowed to make decisions on our own; simple decisions about what we are having for lunch or whether we want to go out tonight, as well as more complicated ones, like having to be actually conscious about how we spend our money since rent is still due at the end of the month.

The part that bothers me most about the importance given to these years is that we are convinced our college experiences will never be surpassed.

The sentiment pretty much implies that not many good things happen after you take off your graduation cap; that after you’re handed a diploma you will be done with all the excitement that life has to offer. Graduating college may be the end of an era, but it is also the start of a new one. It isn’t called a “commencement” ceremony for no reason.

We will go on to do great things in the world—we will become published authors, or CEOs, or teachers, and we will receive awards, start our own businesses, or make our own TedTalks. Yes, being on the executive board of a college club will look amazing on our resumes, but our accomplishments won’t end there.

A lot of us will go on to get married, have children, and meet incredible people who remind us that there is fun to be had in every single thing we do in life. I would hate for us to turn into the forty-something-year-olds we see on television who spend their whole lives yearning for their college years because they have not taken any risks since then. There is no reason to trap yourself in that bubble—you can live your life to the fullest even after your twenties.

Now is a time where we are given the tools we need to nurture our talents. Now is a time of growth and learning, where nothing needs to be set in stone.

We have so much more time ahead of us. It would be a waste to spend it just worrying about what we did in school, instead of wondering about the great things we might get to do next.

Socially, we are told to cherish these years because wWe will never have as much fun.

That’s a lot of pressure to put on the four years you’re supposed to spend studying anyway.

By: Nox Blair

dried and fermented cocoa beans once undisturbed, living in ivory only to be stolen and beat into a piece of American delicacy.

We all want to be youthful forever, having a childlike quality about us. Sometimes, we make ourselves go back to that place without even trying. Ever smell, hear, or do something that takes you right back to childhood?

In an ever changing world, it’s impossible to be serious all the time. I asked 20 people about what makes them feel like a kid again.

10. Photography. I remember as a kid I would always be stealing my mom’s cameras. She never had nice ones, she just liked taking photos of us at sports games or concerts. Whenever we went to sports games as a family I would always beg her to let me take some photos of the players. It’s nice to have my own camera now. It is very full circle from what I have always wanted to do, even as a kid.

09. Walking in the grass, barefoot. Something about it makes me feel like a little kid again, not worrying about getting muddy while I pick the flowers or grass.

08. Buying stuffed animals. Yesterday, I bought two Webkinz and it brought me so much joy.

07. Strolling outside with the sun out. It feels like a fever dream. Everytime it happens I feel like I am daydreaming and thinking of home and my family.

01. Coloring. I remember getting so immersed in the pictures that I was coloring on as a kid and now I still feel the same sense of concentration as I did then. Staying in the lines, tongue sticking out in concentration, all of it.

02. Playing sports. There is something about being active and having such a good time playing a sport that you love that makes me feel so giddy inside and makes me feel like a kid again.

03. Hiking. When I was little, my mom and dad would take me and my brother hiking all over the United States. I don’t have much time to hike anymore but when I do, even if I go on a long walk, it makes me feel at peace and like I’m young again, with no worries.

04. Dancing. Rolling on the floor. Drinking milk with cookies.

06. Watching baseball. My grandpa and I used to watch the Cubs together- it was our thing. Now, I can watch them and feel like a kid spending time with him again

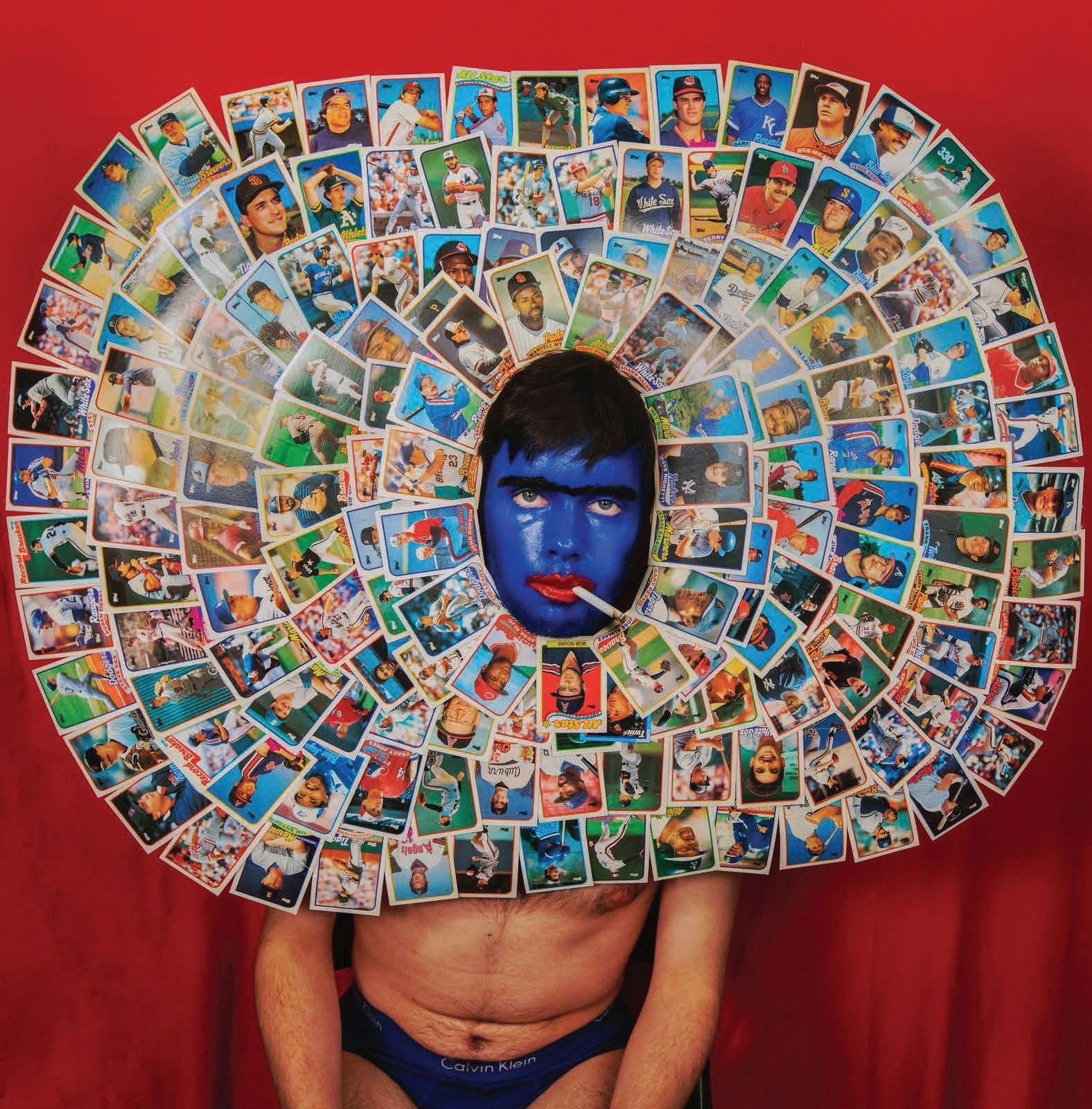

05. Making art collages. My parents used to make me feel like it was a waste of time, so eventually, I stopped. But now that I’m grown, I do it from time to time and it takes me right back to my childhood. Buying cute markers and pens make me feel like it’s Christmas morning.

20. Watch my favorite childhood tv show. It was a huge deal when new episodes came out of the shows I liked because we didn’t have anything to record if I missed them. So whenever I get the chance to watch reruns of them on Netflix, I do it. Sometimes, I can still remember the

19. Watching my dad cook. When I was growing up I would watch him cook every night. After I moved out, I always missed it, so when I get the chance to go home, I make sure to watch and ask to help out.

18. Making bracelets. In middle school I used to make beaded bracelets during recess but I stopped when I got older. Now, I’ll take beads and make little necklaces with my friends’ names on them and it feels really special.

11. Swimming. Some of the earliest memories are swimming in a pool and boating with my family.

Playing video games. I always would play video games with my brother when he would let me.

17. Playing with my cat. I love watching him get so excited and get the zoomies when we play together.

16. Smelling freshly baked cookies. Something about the smell of cookies right out of the oven makes me feel so nostalgic and happy.

13. Sledding. I always wanted it to be winter already so my siblings and I could go sledding and ride down the big hills. Even now on campus, whenever there is a chance, I jump at the opportunity to go sledding.

Having a home cooked meal. It’s not often, a few times a year really, that I can experience and enjoy a home-cooked meal that my mom makes. Something about it makes me feel like a little kid and makes me feel like nothing can hurt me.

15. Reading. You know that feeling when you are so invested in a book, you can’t put it down? That is a feeling I chase after because it makes me feel like I’m in grade school again, sitting on the couch reading after school. No worries, just me and my book.

Written by: Katelyn Barbour

Designed by: Sarah Haddad

Gen Z, Millennials, Generation X, Boomers, so on and so forth, etc. These entities now referred to as “generations” have existed since the beginning of mankind. And, likewise, mankind has always found it easiest to find faults in the youngest of these generations. This phenomenon can be found in any given period of history, and Gen Z is no different.

According to many, we’re technology addicted children with short attention spans and no connection to the real world. We listen to inappropriate, nonsensical music and we have no filter. We’re headstrong and out of our depth. I’m not here to dispute those claims – I’m simply here to put them in context.

Let’s take things back a few centuries. Aristotle once wrote a rather lengthy rant about the younger generations in the Art of Rhetoric, “And they think they know everything, and confidently affirm it, and this is the cause of their excess in everything.” Aristotle’s main point here is that the youth of Ancient Greece are cocky and self-indulgent which, in turn, makes them spoiled and selfish. Essentially, Aristotle has the same opinions about the “youths these days” as your grandfather.

This reflex of Aristotle’s, to blame the young people in society by way of gross overgeneralizations, is not an isolated incident. To tackle some of those Gen Z criticisms mentioned above, I’m going to break down how they have been tirelessly used in various historical circumstances.

We’re technology addicted: It is not an original idea that the younger generations can’t focus on anything except the newest devices. In fact, every major invention has its skeptics. Take the radio, for example. In the 1936 issue of popular music magazine Gramophone, journalists openly feared that children had been engrossed by the radio to the point that “they have developed the habit of dividing attention between the humdrum preparation of their school assignments and the

compelling excitement of the loudspeaker.” The magazine was clearly not ready for the branded “iPad babies” of today. The next time your grandparents make an offhand comment about kids paying too much attention to their phones and not enough attention on their homework, feel free to ask them how their grandparents felt about the radio.

We have short attention spans: Classic technophobia goes hand in hand with the concern that young people will stop taking time to “smell the roses.” Younger generations, according to their elders, increasingly value efficiency over quality of experience and lose the ability to think in a way that older generations did. This concern is also the case in an 1871 article from The Sunday Magazine, where the author states that “the art of letter-writing is fast dying out” and “we fire off a multitude of rapid and short notes, instead of sitting down to have a good talk over a real sheet of paper.” This is a scary parallel to the criticisms of texting that we get today. There is, and always will be, a way to compare our modern forms of communication with those of the past. Gen Z’s texting may very well someday be another kid’s letter writing.

We’re headstrong and risky: A lot of older generations say that young people are impulsive and self-centered. This accusation repeats throughout all of time. Take this quote from 1906’s The Authority of Parents: “There is a great tendency among the children of today to rebel against restraint, not only that placed upon them by the will of the parent, but against any restraint or limitation of what they consider their rights” and “this fact has filled well minded people with great apprehensions for the future.” At some point, the same concerns repeat so often they become cliché, and we have to ask ourselves, “is it the children that are in the wrong here?”

Gen Z’s Progression

Gen Z, for all the grief it gets, isn’t much different from generations past. We probably hear the same criticisms and judgment from our parents and grandparents as they heard from their parents and grandparents. However, that doesn’t mean things haven’t changed.

Gen Z is a revolutionary presence in the history of generations. According to the Pew Research Center, over a third of Gen Z-ers reported that they personally know someone who uses gender-neutral pronouns, and about six out of ten Gen Z-ers say that forms and online profiles should offer gender options apart from “man” or “woman.” These statistics, when compared to older generations’ answers to the same questions, show that Gen Z-ers are far more familiar with and supportive of identities outside of the gender binary.

This one example of Gen Z’s progressive thinking certainly does not stand alone. Even among young Republicans, Gen Z liberalism is taking hold. In fact, over half of Republican Gen Z-ers say the government should be doing more. Compared with the 38% of Millennials, 29% of Gen

X-ers, and even smaller percentages among older generations agreeing with this sentiment, Gen Z proves that it’s moving the future generations further left across the board.

In reality, generations have always grown in ways that defied expectation, and Gen Z is simply following in those footsteps. Although, Gen Z is more ethnically diverse than any other previous generation. We’re also more likely to enroll in college. Gen Z’s unprecedented diversity mixed with our exceptional education leads to a new type of leftism, in which we’re not just tolerant; we’re accepting. The world is growing and changing and Gen Z is out there in it, fighting for the rights of ourselves and others.

However, we can’t let any of the statistics listed in this article go to our heads. If we do, we’ll be stuck in the same pattern of unchanging judgment towards those who come after us. Humanity, no matter the newest developments in technology or legislation, has always been humanity. Mozart wrote a piece titled “Kiss My Ass.” Graffiti found in the streets of Pompeii shows Ancient Romans boasting about their girlfriends and bragging about having sex. Medieval scribes doodled in the margins of their books. Whether it’s in the form of anger or lust or boredom, generations before and after us will continue to embrace and flaunt their humanity, just as Gen Z does.

Generational clash is a tale as old as time. Geezers don’t understand the mindset of teens – their style, their politics, their music, their hobbies – and couldn’t if they tried. But what youth often don’t get is that their identity is transitory.

They may be the most experimental group out there right now, setting the tone for culture and trends, but they won’t be forever. Take the Baby Boomer generation, for example. They came of age in the ‘60s and ‘70s, two decades known for countercultural youth movements, but have spent the last two decades complaining about “kids these days” and being the butt of everyone’s jokes.

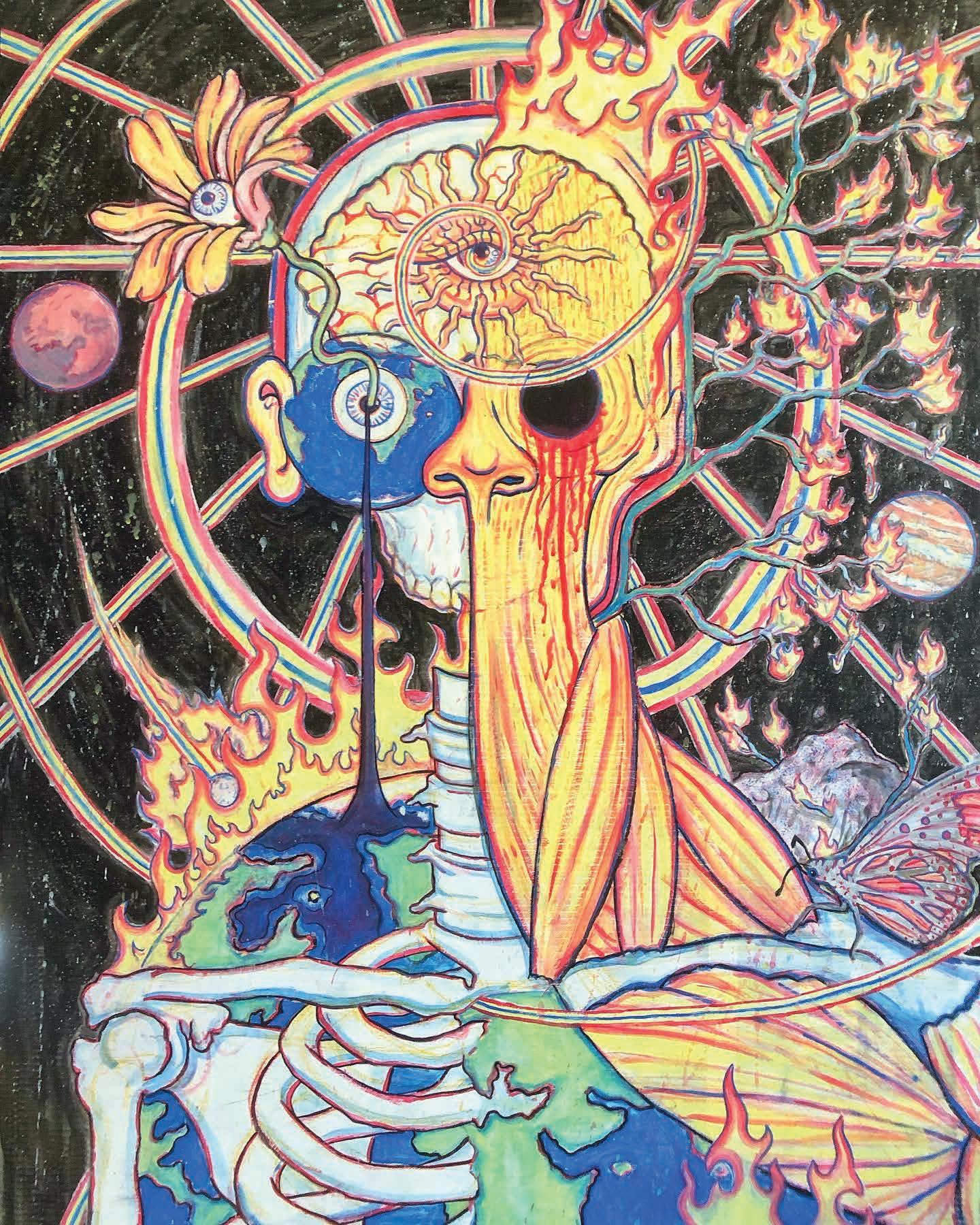

This push and pull between adults and teens has been happening for ages. Youth resistance to the norm will often bubble to the surface of the public eye, transforming from individual angst into shared culture and community all over the world. From the punks of 1970s Los Angeles, to the gyaru of ‘90s Tokyo, and the izikhothane of South Africa today, young people have historically paved the way for expressionistic and personal liberation in the form of cultural resistance.

Punk is thought to have originated in the 1970s across Detroit, New York, and London. The movement started as a continuation of the counterculture movements of the ‘60s (think hippies, free love, and anti-war) with an emphasis on working-class identity and political frustration, especially in the U.K.. The subculture orbits around its music scene, where polish and perfection takes a back seat to a raw and gritty expression of the self. Punk roots lie in the DIY scene and the rejection of conformity. A variety of cultural contexts influence unique iterations of Punk across the world, emphasizing the beauty of decentralization and diversity in the movement.

In Los Angeles in the ‘70s and ‘80s, the Chicano punk scene blended fast rock and Mexican identity in the context of America’s socio-political landscape.

The art born from the Punk scene is extremely personal, and for bands such as Los Illegals, The Bags, and The Zeros, art reflected their experiences growing up Chicano in Los Angeles. Common themes in their music include immigration, cultural clash, troubles in their home life, religion, and discrimination. The DIY aspect of the movement in many ways reflected the concept of rasquache, using any items available (many of which are deemed “non-valuable”) to express oneself artistically, or to create new utility. For many of these Mexican-American Punks, they did not see themselves as vanguards of a cultural movement, but instead as people trying to create a space for themselves. From The Vex, a popular venue for the scene in East L.A., to countless garages, the movement found its home.

Social conservatism in immigrant families, the radical self-expression of the movement and the racism towards people of color from the majority white scene helped to fortify an incredibly strong community: the Chicano Punks of L.A.

In times of national hardship, we see a rapid shift in culture, popular style, and trends. For example, before the 2008 recession, logomania and wearing “it” brands was in vogue. After the recession, fast fashion took off due to its discreteness and affordability, meaning anybody could afford to buy bandage dresses and mustache print leggings. What a win for fashion! Now if we turn back the clock to 1991, we’d see, just like overly inflated bubblegum, the Japanese “bubble economy” pop. The outcome? One word: Gyaru.

At the outset, this fashion-based subculture was a way for the wealthy schoolgirls of Tokyo to subtly rebel against the modest sartorial expectations set for them. The Kogyaru, as they were called at the time, wore designer clothes, rolled up their uniform skirts into miniskirts, wore loose fitting socks, tanned their skin, and lightened their hair. The media proceeded to oversexualize the girls participating in the trend and conflate the style with moral panic and disgrace. However, as the

subculture evolved and expanded, its sphere of influence eventually tapped into the mainstream, featured in magazines and in the marketplace. By the 2000s, the Kogyaru style had morphed into the Ganguro style. This look was more extreme in every way and made the desirable look off-putting to many. The newer take on Gyaru originated from the less affluent neighborhoods of Tokyo, and featured looks appeared to emulate the wealthier Kogyaru look while keeping in touch with their working-class backgrounds. Clothing became brighter, hair became more colorful, makeup became lighter, and skin became tanner.

In an effort to push back against the beauty standards of the time, Gyaru sported deep fake tans dramaticized with white makeup. The media was taken in an uproar of disapproval of the style, spewing sentiments riddled with racism, colorism, and classism. The extremities of the Ganguro look subverted stylistic expectations for teenage girls and young women while still embracing femininity and youth.

In the modern day, the Izikhothane in South Africa are a unique product of the post-apartheid era, comprised of people born after the apartheid came to an end from 1990 to 1994. The social landscape of South Africa, after escaping the trenches of de jure segregation, still maintained many inequalities that existed in the period prior but saw a shift toward increased consumerism. In some ways, the Izikhothane represent the materialism that started to breed in the nation, but their extreme forms of extravagance are what sets them apart from the rest of the popular culture.

This subculture came to prominence in the early 2010’s, making its oldest members at the time a mere twenty years old. Having no experience growing up directly under the conditions of apartheid, these teens were able to experience adolescence with more freedom, and with this came economic liberation. Now, that’s not to say that everybody who belonged to the social strata affected by segregation suddenly came into a higher economic standing. However, the display of wealth and status through consumer products became a popular way to express oneself, and to emulate a higher social standing than what they were societally born into. Izikhothane style

consists of designer pieces, sometimes layered superfluously to highlight extravagance. Groups of teens, or “crews” have dance battles where they destroyed clothes to assert their ability to spend and consume. Most participants in this subculture come from low-income townships, which begs the question: Why consume beyond one’s means? For one, this flashiness increases social capital. But, ultimately, the subculture is a product of South Africa’s Black youth craving a shared identity in a nation that made a huge social shift at the time of their birth, and having no choice but to carve space for themselves in a culture of increased consumerism.

The freshness of being young and the freedom to experiment with personal style, social circles, and art breeds rich subcultures that many adults are not fond of. There will always be a disgruntled commentator taking a dump on whatever trend young people fixate on that year or month or week (it’s so hard to keep up with the trend cycle these days). The irony of it all is that all adults were once teens who were just trying to have fun and build community. They were once misunderstood by their parents or their social surroundings, rebels to the expectations set before them. Maybe it’s the harsh realities of aging and entering the working world that relegated them to a mindset of practicality and stoicism. They can’t push back against the establishment because they are the establishment. Nevertheless, these cultural movements are products of their time, and the legacy of its participants is captured in history in the form of art. Music, photos, videos, clothing, magazine spreads, paintings, and creation of all forms crystallize the youth of people who have had to grow up.

“In

My Car”

By: Sophie Mennenga

In my car

Slid off straps

Shoes and constraints of immaturity

My younger self once wondered

Where I’d be parked

But I’m not parked

We’re moving, driving, gears shifting

Signals of change

Lanes and pains

That reveal my ignored insecurities

Haze of the past

Mixed with the heat of it all

Flowers bloomed

Crashed cars and windows

Glass everywhere

But its edges can’t cut me

Smooth yet lacking grace

But there’s beauty in it

No seatbelt before you

Though no risk of crashing

What a waste to never turn the keys

The patterns. The threads. The fabric. The seams. Today, most people couldn’t really tell you where their clothing came from. Or what the fabric is. Or who made it. That’s not a coincidence. In the past, the United States was a huge producer of garments. Most people knew someone who could sew and possibly worked in a clothing factory or alteration shop. Because of rampant outsourcing to countries around the world like China, Bangladesh, and Vietnam, more and more United States consumers are removed from what it takes to make their clothing.But then came COVID-19. With all the free time in quarantine, a renaissance began. Sewing machines started flying off the shelves of crafts stores throughout the country as people looked for hobbies. While masks were being rationed for frontline healthcare workers, people started making their own fabric masks with easy-to-sew patterns. This was a particularly fruitful time for young people, too. The pillar of Gen Z is the idea of manifesting individual identity, according to researchdone by McKinsey & Company. More young people are interested in personalizing their products and expressing their own identity through that personalization. And so, young people picked up their knitting needles and threaded their sewing machines. The fashion industry is no longer being held at arm’s length.

The first step to any project is the pattern: deciding what you want to make and how you want it to look in the end. This is a lot easier than it sounds.

For Madeline Blair, who owns her own knitting business – called Skyemade – the patterns she designs are typically modeled after her own body. In quarantine, she was about the only person she could measure. Blair started knitting way back in fourth grade. She said she would make tiny squares, in the hope of stitching them all together one day into a giant patchwork blanket. But eventually with age, the hobby faded. That’s until the start of the pandemic. As her classes at the University of Illinois winded down for the summer, she decided to try it again. She bravely decided to make a complicated sweater to start – complete with a cable knit pattern and an off-the-shoulder neckline.“It was really like an advanced pattern and I made it pretty perfectly right off the bat,” Blair said. “I wore it like every day, like the whole year basically.” With one completed, wearable project under her belt, Blair said she kept knitting. As she showed her friends what she was making, and they wanted one themselves, she started to realize she could make them for other people. But creativity wasn’t her only excuse for starting the brand. Yarn is expensive, Blair said, and she wanted to find a way to make up some of the money she was spending. “I wanted to keep having an excuse to make things but then also not lose a bunch of money,” Blair said. Then she got to another issue – the pricing. If she was pricing her knits to pay herself minimum wage

for the hours she spends knitting, Blair said her products would be too expensive for anyone to realistically buy. By the time she spends money on the yarn, shipping, marketing, and packaging, Blair said she had to be okay with just breaking even. “Most of the things on my website are to make sure I don't lose any money from buying the yarn and sending it out,” Blair said. “But I'm also not really making money either.” Because many of the patterns she designs herself are modeled after her own body, Blair said it can be tricky to figure out how to create patterns for people of different sizes. “Unfortunately, buying yarn to make a sweater for a smaller size is far cheaper than buying one to make an extra large,” Blair said “[But] you don't really want to price it by size, because then that gets to be a bit discriminatory, because then if you're thinner than you're paying less money than if you weigh more.” For now, Blair said she’s focused on creating clothing that is structured in a one-size-fits-all way (no, not like Brandy Melville) that’s loose and comfortable so people who wear many different sizes can wear it. As she’s made her way into writing and directing her own films and plays, Blair has started to let actors wear her designs on stage. In the future, she said she hopes she can incorporate more of her own designs into her work. After learning how difficult and time-consuming creating clothes can be, Blair said she’s starting to invest in higher quality pieces she can wear for a long, long time. “I'd rather spend a little more money to have less things,” Blair said. “So that way, I'm not like constantly looking through my drawers being like, ‘Oh my god, I have too much stuff and I don't know what to do with it.’”

Once you have the pattern figured out and a game plan set, it’s time to actually start creating. Again, this is a lot easier than it sounds. You often have to sew things inside out to avoid seeing the seams. Or, fold fabric in an exact way to get the right shape. For Chloe Fulton, she likes to make this process even more difficult for herself. As a creator of historical clothing, she sews almost everything by hand – or without a sewing machine. It’s time-consuming and tedious, but Fulton said she’s trying to make her pieces as they would have been made hundreds of years ago. “I'm getting the feel of how it would have been made in the period with the same look,” Fulton said. “It’s obviously taking a super long time, but I feel like it's worth it for me, not only for the final product, but the experience of making it is really fulfilling.” Fulton studies historical fashion, but she also knows a lot about the history behind the fashion she creates. For example, corsets, although seen as restrictive and torturous to us today, were actually essential to making heavy dresses more comfortable by supporting more weight. Or that men who

were involved in making clothing were seen as artisans while women were seen as frivolous hobbyists. She posts photos of her historical clothing online, where she said she’s found a thriving community of people interested in clothing of the past, too. Fulton also makes some of her own modern clothing, drawing inspiration from touches of historical fashion. (Her favorites are puffy sleeves and linen fabric.) When asked about striking a balance between creating historical and modern clothing, she compared it like this: the non-historical clothing she makes is like reading fiction books, Fulton said. It’s fun and less complicated. The historical clothing is like reading non-fiction books. It’s daunting and requires study and more precision. By having a hand in the creation of clothing itself, Fulton said she has a new outlook on the fashion industry as a whole.“It’s not like robots making these clothes,” Fulton said. “It’s still people [and] I think that people should not only respect the clothing, but also respect the people that made it because they did this labor and it shouldn’t just go away,” Fulton said.

Once you’re finished putting the piece together, it’s time to see if you did everything correctly. Whether it’s flipping it inside out or trying it on, it might require a prayer or two. If you’re planning on selling your product, the hard work isn’t over yet.

For Valerie Morrice, the co-founder (along with Chloe Fulton) of the clothing line Butter Stitch, pricing the clothing they create is pretty fluid. “A teacher said something like, ‘How much money can they give you in your hand andyou feel great letting go right?’ He’s right,”

Morrice said. “So that's how I like to price things.” To keep the price of their products down, most of their designs are printed onto thrifted clothing. This way, the items are unique and they’re not adding more clothing into the fashion cycle. For both Fulton and Morrice, sustainability was important to them as they started theirbrand. It’s a huge buzz word, but it actually takes a lot of effort to implement into your lifestyle, Morrice said.“I feel like sometimes younger people [are] passionate about sustainability, but they're not as willing to commit all of the time and effort,” Morrice said. “Because it's valid. Not everybody has the time or the patience.” Not everybody needs to create their own clothes all the time because there are so many artists like Fulton and Morrice that they can buy clothes from. But, fast fashion isn’t always avoidable, Fulton said.“I think what's more important than that is if you do buy something fast fashion, just respecting it [and] using it for as long as you can and not throwing it away when you're done with it,” Fulton said. The more that Fulton and Morrice scroll on Pinterest and find clothing they’d love to have, the more they start to realize they could do it themselves. With their skills of graphic design, illustration, sewing, crochet, and screenprinting combined, it’s fully possible. “Once you start to make your own clothing, you don't really want to buy more, because you have the idea that you could just make it yourself,” Fulton said.