15 minute read

CSC Members at the Canadian Screen Awards

CSC congratulates the following members whose work in film and television was nominated in various categories for the first annual Canadian Screen Awards.

Best Achievement in Cinematography

Nicolas Bolduc csc, Rebelle Philippe Lavalette csc, Inch’Allah Brendan Steacy csc, Still Mine Bobby Shore csc, Goon

Best Photography in a Comedy Program or Series

Douglas Koch csc, Michael: Tuesdays & Thursdays – Vomiting Ken (Anton) Krawczyk, csc, InSecurity – Anger Management

Michael McLaughlin, The Perfect Runner Derek Rogers csc, Explosion 1812

Best Photography in a Dramatic Program or Series Sponsored by Deluxe Toronto Ltd.

Eric Cayla csc, Bomb Girls – Jumping Tracks David Greene csc, XIII: The Series – Pilot Paul Sarossy csc, BSC, The Borgias – The Borgia Bull Gavin Smith csc, Combat Hospital – Triage

Best Photography in a Lifestyle or Reality/ Competition Program or Series

Joshua Allen, The Tape Stuart James Cameron, Deals from the Dark Side – Houdini Handcuffs Jason Tan csc, From Spain with Love: with Annie Sibonney – Basque Country

Best Direction in a Children’s or Youth Program or Series

Philip Earnshaw csc, Degrassi –Scream, Part Two

The awards will be broadcast live on March 3.

Technicolor On-Location, supporting your vision from set to screen

technicolor.com/toronto twitter.com/TechnicolorCrea technicolor.com/facebook

Grace Carnale-Davis

Director of Sales and Client Services 416.585.0676 grace.carnale-davis@technicolor.com

Boris Mojsovski csc Shoots An Officer nd A Murderer By Fanen Chiahemen

Russell Williams (Gary Cole) is asked to answer a few questions. Frame grab from An Officer and a Murderer.

Perhaps it was only a matter of time before the story of Russell Williams – the former Canadian Forces colonel, who in 2010 was convicted of serial rape and murder – would be retold in movie form. But that didn’t make it any easier for Boris Mojsovski csc to digest the idea that a made-for-television drama was in the works.

“I thought, ‘Why would anybody want to write this script? What’s the redeeming feature?’” Mojsovski recalls. But after reading Keith Ross Leckie’s script for An Officer and a Murderer, which was directed by Norma Bailey and stars actor Gary Cole as Williams, the director of photography was intrigued.

“It doesn’t go into the details of how the murders were committed,” Mojsovski says. “It just follows the murderer, and we see that people like that are all around us. The scary part was that he was just an everyday guy who happened to be the commander of the biggest air base in Canada. And that’s what I found most interesting.”

That philosophy was in fact what informed the filmmakers’ approach to the look of the film, which was shot in three weeks in Toronto and Unionville, Ont. “We never wanted to create a look that was too stylized because of that aspect of reality,” Mojsovski says. “We wanted to present the world as if this can happen anywhere at any time. It was a simple approach, and I really didn’t want a lot of gadgets because the story wasn’t about that. If I used gadgets it would have stylized the image. I just wanted it to be streamlined and simple.” To that end, he and Bailey decided the film should be “warm in the beginning and then we’d go slightly de-saturated and a little bit cooler,” Mojsovski explains. “As the killer progressed in his quest, our look got darker and cooler.”

Working with production designer Gavin Mitchell, Mojsovski pushed to find the right interior locations that would uphold the look without the need for too many gadgets. “That is, interiors with darker walls, neutral colours, no primary or secondary colours,” he says. “Trying to just allow the faces and the skin tones to be basically the most colourful part of the image. Because you focus on the actors that way subconsciously.” He also tried to keep the skin tones as natural as possible. “So you could see a little bit of pink and a little bit of magenta in the skin tones, and that helps the realism,” he adds.

Mojsovski lit most of the film with big soft sources. “I just like the feel of the big sources inside the room, and then you don’t

need a backlight or any other supplemental lights,” he says. “And it suggests realism. When you have soft light your eyes adjust to it much more easily. Also, you want a face lit with a soft light because it looks better and the viewer accepts it.”

However, controlling such light sources on a three-week shoot was problematic. So Mojsovski had two main interior lighting setups, which he and the crew dubbed “the big monstrosity and the small monstrosity.”

What he called the “big monstrosity” consisted of eight or more Kino Flos behind a 20x Muslin or light grid suspended on a TBar. “It looks very scary,” Mojsovski says, laughing. “But I really like it because it’s organic and easy to move even though it doesn’t look like it is.” The smaller light fixture, the “small monstrosity,” had just two or four Kinos.

For daytime interiors of police station scenes, Mojsovski would place a row of five 18K HMIs on lifts, and the light outside would sift through the windows through unbleached muslin, and then the interior light setups – the monstrosities – would shape the close-ups.

For night interiors, Mojsovski would supplement the smaller “monstrosity” setup with strategically hidden lights and just glow the windows slightly cooler to simulate moonlight.

“So that approach saved us in many ways but gave us that very soft contrast-y look. We gave the images as much shape as we could,” he says.

Mojsovski also tried to avoid having hard light hitting the actors’ faces. “With the soft light coming through the window and from what looked like practical sources, the viewer associated that with realism because it looks like the practical lamp or the window is lighting the actors.

“But I never overdid the contrast,” he adds. “The film is never too dark. So you never feel the style overpowering the story. We always shot with the camera on the dark side to consistently have proper shape on the faces.”

Shooting exteriors was more challenging because of the number of houses in the neighbourhood locations. Mojsovski ended up lighting a whole block, relying on his team for precise placement, as there was no time to move lights. “Without my gaffer, George Kerr, and the grip, Felipe Rodrigues, I don’t think we could have done it. I mean, they were the heroes of this production,” he says.

The DOP recalls a sequence that required shooting three houses at night. “What George, Felipe and I decided to do was put condors on two sides of the action, at both ends of the street in case we wanted to turn around, right away we would be ready to start burning the lights on both sides of the street and basically cover an area of 500 metres,” he says.

In one crucial scene, the Williams character comes out of his house and hides so as not to be seen by the police. “We simply

Credit: Stephen Scott

DOP Boris Mojsovski csc talks to Laura Harris (playing Detective Jennifer Dobson).

could not figure out where to put another condor to light that part of the house. So finally we hid a 20K in some bushes. It was the only way to hide it from the camera and the only angle that would work for the bounce.

“It saved us a huge amount of time,” he continues. “If we’d brought another condor around we would have lost a lot more time and resources. It allowed us to do something in 15 minutes instead of waiting for an hour.

“The support of the producer Mary Young Leckie and the line producer Lena Cordina was crucial for our success. They gave us access to all the gear necessary to move quickly and efficiently; they were great,” Mojsovski says. Having shot several made-for-TV movies, Mojsovski is accustomed to the three-week shooting schedCredit: Dave T. Sheridan ule they typically require. But usuFive 18Ks on lifts lighting the ally on those movies, he says, “the police station interior. story fits that time-frame because there are a few locations and not many cast members. Here we had 20 locations and they were all quite complex locations. Every scenario that you can imagine would be difficult to do where you really need the time to do it, well, we had to do it in three weeks.”

Sometimes the crew tried time-saving methods like placing the two ALEXAs (fitted with Ultra Prime lenses) on the same dolly to shoot close-ups and wide shots at the same time.

But it also helped that the production had “great actors who really did a great job,” Mojsovski says. “We didn’t have a lot of takes because we didn’t need a lot of takes. The actors did really well. It was a really well-oiled machine. Everyone cared a lot because of the story.”

His

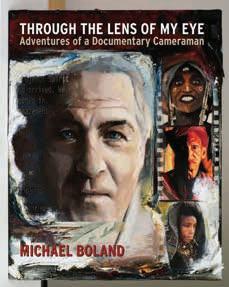

Lens: o ugh Michael Boland csc Shares His Adventures

Credit: Marco Preti

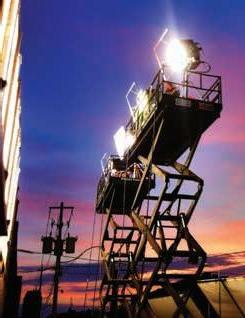

Michael Boland csc 60 feet up on a filming platform.

Michael Boland csc started out with a career in hockey, playing professionally for seven seasons, including some games in the NHL with the Philadelphia Flyers. Then a chance encounter at an Australian television station landed him a job as an assistant cameraman, and he spent the next 35 years travelling to every corner of the world, including some of its remotest spots. From filming gorillas in the N’Doki rainforest of the Congo with Bembemgele pygmies to climbing Mount Everest, Boland has racked up some remarkable adventures. Now in his recent memoir Through The Lens of My Eye, he shares some of the best tales from his journeys.

Canadian Cinematographer: In the book you describe how your mother encouraged you to take lots of pictures and notes on your travels so she could live vicariously through you. But how did you manage to capture all those memories in such detail?

Michael Boland csc: I would be on a documentary shoot, and I’d spend the day shooting and then be writing in my tent at night, because I found it interesting. So I have word-for-word, day-for-day verbatim conversations. I never started out with the intent of writing a book. I just tried to busy myself documenting the day. There’s a good core of documentary cameramen in Canada, and they say to me, “I would have liked to have done that too, but I can’t.” No one else really took journals or took copious amounts of still pictures. I started writing this stuff 12 years ago. It took 12 years to get it all down.

CC: You got into the documentary shooting business in the late 1970s after an Australian friend told you about an opening for an assistant cameraman at a TV station. You were hired with no experience and learned on the job. Is that still common today?

MB: I don’t know if it could happen today. Maybe not. Maybe

hr T

you’d have to go to a George Brown College or Humber College. But it’s still competitive. Only a few will do it. You’re competing against some hot shots. Is it possible to have a similar career? Yes. It all comes down to drive, ambition, talent, luck, and fate. A lot of young people say, “I want to do what you do.” And I ask them, “Where are you now?” And they say, “I’m in fourth year of media studies. And I’m hoping next year I’m going to be doing what you do.” And I tell them, “You can’t do what I do within 12 months. You have to have a reputation. It takes a long time to get there.” So [with this book] I wanted to give them an idea of what’s possible – that it’s colourful, wonderful, interesting, fascinating and hard work. It has ups and downs and trials and tribulations. I wanted to give them enough impetus but at the same time not delude them that they’re all of a sudden going to step into it.

CC: What’s the most important thing you tell people who want to follow in your footsteps?

MB: The art of the documentary business is the art of telling the story. That’s what I tell young people coming out of college. When I go out to shoot a documentary, I know character development, I know story development. That’s a learned process. If you’re talking about focus and craning and lighting, I could teach you that in a crash course in about probably a month. The storytelling takes a lifetime. And quite frankly a cinematographer’s job is to assist in the telling of a story. The directors and producers trust you to know the technical aspects. They’re interested in telling a story. So, consequently, my book is about the telling of a story. Utilizing the camera as a tool to tell the story.

Accuracy, Simplicity, Compatibility

“This technology represents the essence of forward compatible, forward thinking metadata support. Open source, anyone can use it, high degree of accuracy. Ten stars out of a possible five for providing for the digital future of cinematography. Bravo!”

David Stump ASC, DP/VFX Supervisor

What Happens in Post Determines the Look of Your Final Product

Your film isn’t finished until it’s up on screen. We know how important that final look is, so we designed and built digital “ Technology” into our lenses. Frame-by-frame Data Capture

Technology is a metadata system that enables film and digital cameras to automatically record key lens data for every frame shot. Metadata recording takes place without having to monitor or manipulate anything so normal operations on set are not affected. No specialists required. And, manual entries in camera log books will be unnecessary, so you’ll save time in production. That’s important. No More Guesswork in Post Effects artists will save hours of time when they have to composite a creature into your masterful 16.4mm to 32.7mm eight second zoom, during which you followed focus from 65 to 12 feet at T2.8 1/3. With metadata automatically recording your every move, you just saved the guesswork in Match Moving and mountains of paperwork in post. Your producer saves time and money. You are a hero. Open Source To date, companies including Aaton, Angenieux, Arri, AVID, Birger Engineering, Cinematography Electronics, CMotion, Codex, Element Technica, The Foundry, Fujinon, Mark Roberts Motion Control, Pixel Farm, Preston Cinema Systems, RED, S.two, Silicon Imaging, Service Vision, Sony and Transvideo have incorporated Technology into their hardware and software products. Your Secret Weapon Using means consistent, accurate lens data for every frame of every shot and a great final product with no disruption to your normal work on set. Join the evolution. Capture it, use it, and see for yourself.

For more information see: http://imetadata.net/mlp/join-i-technology.html

Join the evolution and become a Contact info@imetadata.net Partner.

MB: You’ve got to be thinking on your feet. A drama cinematographer has a gaffer, a grip and a crew of 20. My job is to run myself. And I’ve been on a few drama sets, and they’d all go, “Lucky bugger! I wish I could do what he’s doing.” When you go on these kinds of trips you become not only great friends hopefully with the people you’re working with, but also with the people you’re filming. When you have a heart and you show your heart, people recognize that and you become friends.

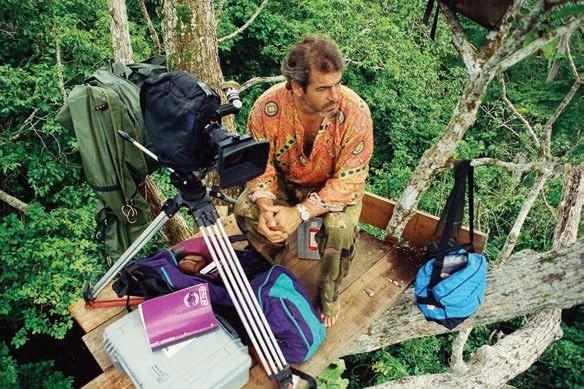

Excerpt from Through The Lens of My Eye: Adventures of a Documentary Cameraman

“Quiet!” The middle-aged Frenchman with the tattered shorts and the unkempt beard commanded us. His eyes flashed wildly in anticipation of what we were about to see. He frantically motioned for us to remain still, then darted ahead leaving us only imagining what lay around the next bend on the rainforest path. The first shards of the dawn light had only just broken through the jungle canopy. My Italian co-cameraman, Marco Preti, and I had journeyed two hours in the darkness of early morning, led by five Bembemgele Pygmies and this most strange maverick, Michel Coutois, equipped with a lone flashlight. He returned shortly after and instructed us to follow. Carefully, cautiously we edged our way down the muddied path trying not to snap a fallen

© Kodak 2013. Kodak and Vision are trademarks.

WHEN YOU CHOOSE TO ARCHIVE ON FILM, YOUR WORK LIVES ON. Film is more than entertainment, it’s history. Without it, countless classics would be lost. Now, as digital storage becomes more seductive, modern classics could face extinction. If it’s worth shooting, it’s worth saving. Protect your legacy on KODAK Asset Protection Films.

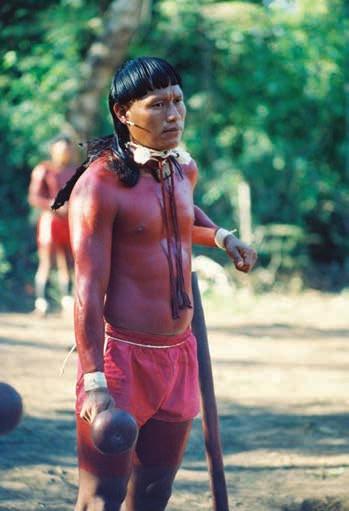

Find out more at www.kodak.com/go/archive Travels with the first peoples of Peru and Brazil.

twig or brush our camera equipment against the jungle foliage.

“They’re here,” he whispered. “Try not to make any sound. Just climb the platform and start filming.” Marco and I stepped waist deep into the murky water and waded some 50 feet, whereupon the jungle opened up to a clearing called a baille, the Bokumbela baille to be exact, a square mile swamp created by generations of watering animals. It was the only clear, open space in an otherwise claustrophobic jungle. When we reached the base of a large African hardwood tree, I looked up and saw the constructed platform. Marco ascended first, then cast down a rope in order to haul the camera equipment up the 25 yards to our filming position. I secured my camera in a rucksack and began the ascent up the primitively-constructed ladder. Having just hiked six kilometres, my legs were shaking as I progressed up each rung of the terrifying climb. I was drawing on adrenaline to prevent tumbling from the heights. Finally, I reached the top and Marco grabbed my jacket collar and pulled me aboard. We assembled the gear with as much precision as we could muster and then switched the camera on. Four green-grey forest elephants were dining in the marsh pond not 300 yards from us. To film forest elephants in the French Congo is rare to say the least. A broad, crazed smile beamed from the face of the Frenchman whom we would come to know soon enough. This was our first day of filming in this most tropical of jungles, having arrived only two days previously.