22 minute read

CSC Members Win at the Canadian Screen Awards

CSC congratulates the following Canadian Screen Award winners

Best Achievement in Cinematography

Nicolas Bolduc csc, Rebelle

Best Direction in a Children’s or Youth Program or Series

Philip Earnshaw csc, Degrassi – Scream, Part Two

Best Photography in a Dramatic Program or Series Sponsored by Deluxe Toronto Ltd.

Paul Sarossy csc, bsc, asc, The Borgias – The Borgia Bull

Best Photography in a Variety or Performing Arts or Sketch Comedy Program or Series

Dylan Macleod csc (with Pierre Marleau), Love Lies Bleeding

�s sss nssns ss ssssssnss sss ss� �� ��� ssss �ss

�sssss� sssssss sss ssss sssssssss� sns����� ssss �sss�sss �snssss�sss �sssssssssssssssnsnssssnnsssssssss� sssssss��ss�nn�ssssssssssssssssss

Grace Carnale-Davis ssssssss sssssss sss ssssss ssssssss ssssssssssss sssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssss

Technicolor On-Location nnnnnnnnnn nnnnnnnnnnnnnn nnnnnnnnnnn

technicolor.com/toronto

Iris Ng Telling Sarah Polley’s Stories

By Fanen Chiahemen

There’s a family secret revealed in Stories We Tell, the first feature

length documentary by Toronto native

Sarah Polley. But it’s not the secret that’s

under examination here, but storytelling

itself and how each person’s version of the

same story can cause the truth to mutate.

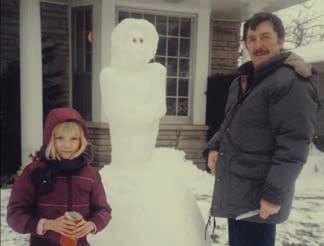

Scene from Stories We Tell.

Left to Right:

Sarah and Michael Polley.

Courtesy of the National Film Board of Canada 2012. The documentary captures that essence by interweaving testimonial-style interviews, home movies from the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s – shot mostly by Polley’s father, Michael – with dramatized recreations of events shot to look like they were captured during that era.

“[Polley] wanted to closely match the 8 mm archival footage shot by family, and to blur the lines between what was archival footage and what was an interpretation of the past,” director of photography Iris Ng explains. “The intention was not to trick the viewer but encourage them to question what they were seeing. To wonder how much is fictionalized and filling in of gaps, which tends to happen when you’re dealing with something that occurred 30 years ago.”

It was Ng’s use of Super 8 film on another project that brought Polley to the cinematographer. “Iris made a beautiful short film several years ago called Point of Departure which examined her own family history in a really innovative way,” Polley says. “I remember the film opened with a Super 8 shot, and it moved me to tears, partially because of the way the format itself was being used. The aesthetic and tone of her film became the seed of inspiration for Stories We Tell.”

Ng used the format for the recreations, and the production amassed several Canon 1014XL-S cameras – the DOP bought one herself from another filmmaker, while the National Film Board purchased several from New York-based Du-All Camera and rented from CSC member Justin Lovell. She shot with the Kodak Ektachrome 100D reversal film (7285), as it was the closest film stock to the Kodachrome, which had been discontinued but was commonly used in that era, having an inherent smoothness to the grain and a distinctive falloff in the shadows.

“We tested a whole bunch of stocks – negative mostly – which captured so much more information,” Ng says. “Even though we had the option of manipulating them in post, it was apparent, as my colourist Mark Kueper offered, that ‘right out of the box,’ the reversal had all the inherent qualities we were going for.”

Because the film was a daylight stock, Ng primarily had daylight balanced light, namely 400W up to 6K HMIs, Kino Flos, and Photoflood bulbs, playing them as motivated sources whether they were practicals or natural daylight from outside a window. Also, Ng noticed in watching the authentic archival Super 8 footage the use of a spotlight that was obviously mounted on top of the camera. “I think because Kodachrome came in such a low speed at the time, probably 40 ASA, that for any interior shooting they would need these sun guns,” she says. “So in the interior scenes of the home movies, you would see someone lit by the spotlight, and everything in the background would quickly fall off. That was the case for a lot of home movies from that era because of the low film speed.”

So Ng did some research and found an array of sun guns that could be mounted on cameras, eventually procuring from Craigslist a Kodak Instamatic Movie Light that could be attached to certain Super 8 cameras of the time. “I tested the effect with the Instamatic and found that it reproduced the same quality and intensity we were seeing in the home movies, so key grip Zach Zohr created a mini rig which allowed it to be positioned on top of the camera,” she explains. “Although not conventionally desirable because it was flat and created an obvious shadow behind the subject, it really sold the look we were going for. But because we were shooting at a low speed and on a daylight-balanced reversal stock, it was particularly hard to balance the colour of that light. And it was way too hot to place a gel anywhere near it, so using an 80C filter on the lens was a happy medium between losing two stops with a full correction and having too far to go in terms of balancing the colour in post.”

Although the recreation scenes were challenging to light, they were also exciting for Ng because it required her to embody the character of the person who shot the archival footage she was trying to emulate. To that end she would mimic the shooting styles she observed in the home movies. For example, she noticed that Michael Polley would often use an “in-camera editing trick” while shooting. “There’s a shot of Diane [the director’s mother] lying on the grass, and he shoots about two seconds of her straight on, and he stops the camera, and clocks it 15 degrees, and then there’s another burst where he shoots another two seconds, and he repeats this maybe eight times in a sort of pinwheel fashion, and it’s just one of those playful things that he did very spontaneously, but it was something that I mimicked during one of the more playful moments.”

Images on this page: Courtesy of the National Film Board of Canada 2012.

Above: Stories We Telldirector of photography Iris Ng, left, with director Sarah Polley. Middle: The director’s father Michael Polley in Stories We Tell. Bottom: Scene from Stories We Tell. Left to right: Michael Polley and Sarah

Polley.

Ng also noticed that when Michael Polley was operating the camera he would frequently pan away from the human subjects and shoot what was in the background, say a field or a rooftop. “As he mentions in the beginning of the film in his interview, his style of shooting home movies was not to pay attention to the people too much. So I would keep that in mind and I would drift when shooting in the way that Michael’s camera might have drifted to emulate that style he has.”

This technique served to make it more difficult for the viewer to identify a scene that had been reconstructed, Ng says. “If the attention was always on the central character, I think the con- nections would have been too literal; it would give away the fact that they were recreations.”

Ng would also sometimes operate the camera in such a way that it looked amateurish. “I had to embrace the flaws that a novice shooting home movies might make,” she explains. “Like things going soft sometimes or second-guessing one’s panning or tilting at times.”

Because shooting in Super 8 meant having a turnaround of two days to see dailies – by which time the crew was usually out of

Also, as Super 8 was “a format that was never meant to be professional,” Ng says she did not always trust the camera to hold up. The solution, she and the crew decided, was to shoot a take they were happy with and then capture another take on a backup camera. “We would always have two in use, plus any backups ready, knowing one would jam or fail in some way. In total, we went through six cameras over a three-week shoot.”

Shooting the testimonials with Sony F900-Rs was a lot more straightforward. “We wanted a very naturalistic look so we wouldn’t be imposing a heavy-handed visual interpretation that would influence how the viewer should feel about the story or the storytellers. We just wanted something very neutral.” During interviews, Ng would situate the subjects beside a window with diffused light, shooting them at a medium range to discourage too much focus on their emotions. “We weren’t always in situations where there would be sufficient natural light, so I would have a 575 HMI or tungsten fixture with CTB on hand, which I diffused and did my best to play as natural light,” she says. Throughout the documentary, behind-the-scenes style shots of Rather than undermine the narrative, the divergent techniques and approaches to composition that went into making Stories We Tell ultimately converge into a compelling film, and Polley’s faith in Ng’s instincts and judgment went a long way to bringing together the final product.

“Sarah’s a very collaborative and trusting director, and I think this film especially put that to the test because shooting in Super 8 you have no means of monitoring what the DOP is doing,” Ng offers. “And she put that trust in me from the very beginning, and that allowed me to be free to follow the action in the way that I felt was the most natural. It was just a great

experience.” © Kodak 2013. Kodak and Vision are trademarks. VANCOUVER CALGARY TORONTO HALIFAX 604-527-7262 403-246-7267 416-444-7000 902-404-3630 Client: _____________________________________________________ Docket: ________________ Media: _____________________________________________________ Placement: ____________ Trim Size: ______________________ Safety: ____________________ Bleed: ________________ Colour: ________________________ Publ. Date: _________________ Prod. Date: ____________ Panavisi on Canada PAN-COR-1 634-08R1 CSC News 5.25" W x 2.1 25" H N/A N/A B&W 201 0 Jan 7, 201 0 VANCOUVER CALGARY TORONTO HALIFAX 604-527-7262 403-246-7267 416-444-7000 902-404-3630 the crew filming the subjects are interspersed among the recreations, home movies and testimonials, a device that came about somewhat organically, according to Polley. “When we were shooting our first interview, Iris had the idea to shoot some B roll of behind-the-scenes footage on Super 8 since we knew we would be using so much archival Super 8 in the film,” the director recalls. “When we watched the footage we realized that it helped articulate one of the central ideas of the film – the feeling of nostalgia triggered by the format immediately calls into question the accuracy of memory, and how a moment that has only just been captured or lived is already relegated to the past and is unknowable and its truth subjective.”

Stories We Tell Tel: 416-423-9825 Fax: 416-423-7629 E-mail: dmaguire@maguiremarketing.com

Camera formats:

Interviews: HD-CAM - Sony F900-R “Archival” recreations: Super 8 - Canon 1014XL-S (Kodak 7285 100D), transferred at Technicolor New York

Real archival footage: Regular 8 mm (transferred at Frame Discreet) Behind the scenes footage: Super 8 - Canon 1014 Auto Zoom, Nikon R8 (Kodak 7219 500T, 7213 200T)

Client: _____________________________________________________ Panavisi on Canada Docket: _______ PAN-COR Media: _____________________________________________________ CSC News Placement: ___ WHEN YOU CHOOSE TO ARCHIVE ON FILM, YOUR WORK LIVES ON. Trim Size: ______________________ Safety: ____________________ Colour: ________________________ Publ. Date: _________________ 5.25" W x 2.1 25" H N/A B&W 201 0 Bleed: _______ Prod. Date: ___ N/A Jan Film is more than entertainment, it’s history.

Tel: Without it, countless classics would be lost. 416-423-9825 Fax: 416-423-7629 E-mail: dmaguire@maguiremarketin Now, as digital storage becomes more seductive, modern classics could face extinction. If it’s worth shooting, it’s worth saving. Protect your legacy on KODAK Asset Protection Films.

Find out more at www.kodak.com/go/archive

“Modern-day” recreations: Super 8 - Nikon R8 (Kodak 7219 500T, 7213 200T)

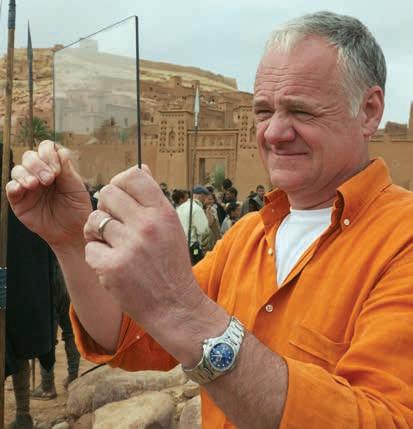

Robert McLachlan csc, asc Plays

Game of Thrones

By Fanen Chiahemen

Robert McLachlan csc, asc in Morocco utilizing Schneider Optics’ Hollywood Black Magic filters on Season 3 of Games of

Thrones. Previuos page: Candles are used

often in Game of Thrones.

Being enlisted to shoot a couple of episodes of a series as popular and acclaimed as Game of Thrones comes with its fair share of pressure. As Vancouver and Los Angeles-based director of photography Robert McLachlan csc, asc remarks, after two successful seasons, “the bar has been set pretty high.”

What McLachlan discovered, when he teamed up with director David Nutter to film the climactic last two episodes of the HBO series’ third season, was that for all its intricate plotlines and fantasy elements – the series features seven noble families warring for control over a mythical land –the key to maintaining the show’s standards was to keep things pretty simple.

McLachlan says Nutter favoured substance over style, in keeping with the show’s ethos. “The template as a rule is quite naturalistic, and as much as possible true to the era we’re supposed to be shooting in where there aren’t a lot of artificial sources of light,” the cinematographer explains.

This meant using natural light or modified natural light as much as possible, softening with negative fill when necessary to give some modelling to a subject. The ARRI ALEXA helped facilitate the show’s shooting style even in low-light situations, and it was thanks to the camera that McLachlan was able to capture a scene he says is going to be the series’ most shocking yet – a scene he filmed almost entirely with candlelight.

McLachlan explains, “It starts with a big happy occasion, and what I wanted to do with the scene was put the viewers at ease. On Game of Thrones even the simplest scene is shot in a very contrasty, moody, dark light, with a lot of dark shadows where things are lurking. So I lit this hall quite a bit brighter by Game of Thrones standards. I had the art department put extra torches in and twice as many light sources as I would normally have, Credit: Sean Leonard and I brought the light levels quite a ways up substantially, just to get the viewers subconsciously feeling there’s no way anything bad can happen. “And then, organically, within the scene there’s a point at which the party is led out of the hall and most of the people leave, and because it’s obviously dark throughout the rest of the castle, I got all the extras to grab most of the torches and candelabra and leave with them. So as they walked out, they picked up the actual instruments that were lighting the scene, and the hall naturally got much darker and suddenly spookier, and that’s when really horrible things start to happen. The beauty of the candlelight made a really fantastic visual counterpoint to the brutality that followed.”

With so few candles left in the room, it was just a question of adding very soft studio light to pick up some of the residual smoke that was in the air from all the candles. He adds that he often uses smoke as a lighting tool. “Slightly backlit smoke

Still from Game of Thrones.

becomes your fill light, so you don’t have to throw a bunch of other light in from the front, and you end up getting a much more naturalistic feeling, so in this case I was doing the same,” he says.

By using smoke for fill light, which helped open the shadows up, McLachlan could often get away with a 20K just outside a window streaming in – when shooting in a large castle hall, for instance – and almost no extra fill light from the floor. “Also, we used this wonderful unit we hadn’t used before made by Dedolight called the Octodome; it’s one of my favourite lighting tools,” McLachlan says. “It just throws an incredibly soft light; it doesn’t have a very deep profile. One person can move it around, and we usually softened it through a full grid cloth. There was no unmotivated backlight ever used.”

To help maintain the visual continuity throughout the series, which switched out the director and DOP every two episodes, the cinematographers, directors, producers and executives, were given new retina display iPads loaded with the PIX System for posting dailies. “You just downloaded it off the Internet and everything that was shot throughout the season was loaded on it, as well as episodes from last season,” McLachlan explains. “You could go in and see what somebody had done either the day before or the year before on a similar set. I think by and large people won’t see much of a difference from DP to DP.”

For the episodes he shot, McLachlan worked in Croatia, Morocco and Northern Ireland, and he adopted a simple philosophy to deal with the unique obstacles each location provided: “You take what you’re given and work with that as best you can rather than fight it. Because when you fight what you’ve got visually or go against what the location gives you in terms of natural light and conditions, and look and feel, you generally fail.”

Fortunately, working on such a large production, McLachlan was granted the luxury of time to plan ahead. For example, in June of 2012 when he and Nutter scouted locations in Morocco, where they would be shooting in November, they used sun-tracking software uploaded on an iPhone to determine exactly where the sun was going to be at the time they would be shooting. “So we had four months to formulate our plan for how we were going to shoot it,” McLachlan says. “That way you’re not dragging a lot of cranes or lighting lifts around. You can just let Mother Nature do it if you’re in the right place at the right time. It turned out really gorgeous, and we were able to use natural light and none of our own light. It’s when you’re fighting the elements and shooting a scene that’s taking forever, and not necessarily where or when you want to be doing it, that you have to start pulling out a lot of equipment to control it.

“That’s why throughout my whole career I’ve always pushed directors as much as they could to know before they get to a location how and where they were going to be shooting, where they want to look and how the scene is going to be blocked,” he continues. “Most don’t like to be nailed down that much for whatever reason, but most of the directors they had on the show this year either understood or were made to understand by the DOP that we had to work this way.”

What McLachlan struggled with abroad was adjusting to the way jobs were classified. “In Britain they don’t have grips like we’re used to having in North America,” he explains. “It comes down to the rigging crew to do a lot of that stuff. When you need a big green screen on location, it’s a bit more of a cumbersome process there than it is here. Here if you need a 12 or 20 x frame or something you tell the grip, and it’s usually up in a flash. In the British system the electrical department does all the lighting stuff, as well as light modification, so things that would normally fall in the grip department here are all under lighting department there.”

McLachlan credits much of his success on a show of such scope to his working relationship with Nutter. “I’ve worked with over 250 directors, and I’ve never worked with anyone more prepared than he is. When you have someone that dedicated and experienced who has all their ducks in row and knows exactly what you’re meant to do, it just makes a huge amount of difference,” he says. “But quite apart from that, he is an absolute prince of a man – kind, empathic and generous to a fault. The cast and crew are all demonstrably happy when they know he is directing that day.”

Accuracy, Simplicity, Compatibility

“This technology represents the essence of forward compatible, forward thinking metadata support. Open source, anyone can use it, high degree of accuracy. Ten stars out of a possible five for providing for the digital future of cinematography. Bravo!”

David Stump ASC, DP/VFX Supervisor

What Happens in Post Determines the Look of Your Final Product

Your film isn’t finished until it’s up on screen. We know how important that final look is, so we designed and built digital “ Technology” into our lenses. Frame-by-frame Data Capture

Technology is a metadata system that enables film and digital cameras to automatically record key lens data for every frame shot. Metadata recording takes place without having to monitor or manipulate anything so normal operations on set are not affected. No specialists required. And, manual entries in camera log books will be unnecessary, so you’ll save time in production. That’s important. No More Guesswork in Post Effects artists will save hours of time when they have to composite a creature into your masterful 16.4mm to 32.7mm eight second zoom, during which you followed focus from 65 to 12 feet at T2.8 1/3. With metadata automatically recording your every move, you just saved the guesswork in Match Moving and mountains of paperwork in post. Your producer saves time and money. You are a hero. Open Source To date, companies including Aaton, Angenieux, Arri, AVID, Birger Engineering, Cinematography Electronics, CMotion, Codex, Element Technica, The Foundry, Fujinon, Mark Roberts Motion Control, Pixel Farm, Preston Cinema Systems, RED, S.two, Silicon Imaging, Service Vision, Sony and Transvideo have incorporated Technology into their hardware and software products. Your Secret Weapon Using means consistent, accurate lens data for every frame of every shot and a great final product with no disruption to your normal work on set. Join the evolution. Capture it, use it, and see for yourself.

For more information see: http://imetadata.net/mlp/join-i-technology.html

Join the evolution and become a Contact info@imetadata.net Partner.

Greig Fraser acs, director of photography on Zero Dark Thirty.

Shooting Zero Dark Thirty

By Bryant Frazer, StudioDaily.com

With awards season running at full throttle, much ink has been spilled about the political implications of Zero Dark Thirty. The controversy has nearly overshadowed director Kathryn Bigelow’s pulse-quickening achievement in translating the boots-onthe-ground details of the CIA’s long-running manhunt for Osama Bin Laden to the screen. The press and punditry will continue to dissect the film’s attitude toward torture. Meanwhile, we dug into some of the behind-the-scenes details of the film’s making that have been released in various outlets to pull out some nuggets about how Bigelow’s crew pulled off the immense feat of principal photography.

10 Tidbi s from he Trenches

1Director Kathryn Bigelow and cinematographer Greig Fraser ACS chose the ARRI ALEXA because of demanding low-light conditions in the film’s climactic raid sequence. “It was a very specific decision, driven in part by the need to capture the low light of the raid in Abbottabad,” Bigelow said. “The cameras are wonderfully sensitive to light, so we were able to utilize the softest, dimmest light source possible, allowing us to more accurately simulate a moonless night.” 2 3 ARRIRAW data was recorded to Codex Onboard M recorders. For scenes when the camera crews were working handheld, Codex recorders and other accessories were mounted on special backpacks given to the camera assistants by Digilab Services. Digilab also redesigned the Codex Datapacks, modding them to replace their aluminum shells with lightweight injection-molded plastic.

The brand-new LTFS tape offloader module from Codex was used to archive the 276 hours of footage gathered during the shoot to LTO-5 tape. Dailies were graded using the ACES colour pipeline, and DNxHD MXF media was rendered out for editorial. Fraser and production designer Jeremy Hindle were close personal friends, making collaboration quick and easy. “Every time there was a shot that looked like it was a reference to another movie, Greig and I would look at each other and say, ‘Oh God, we shouldn’t do that,’” Hindle explains. “So we’d change it to look a little less familiar, and strip it back to be as bare and natural as possible.” Shooting in Chandigarh, India, was difficult because of huge crowds gathered to watch the Western filmmakers. “We found that one way to solve this was to distract a crowd with ‘fake shoots,’” said producer and screenwriter Mark Boal, “including one where we had one of our grips dancing, while we got the actual shot we needed elsewhere.” 4 5 6 7 8 9 Even though the stealth helicopters used in the film’s climactic sequence were CG, VFX supervisor Chris Harvey recommended shooting real Jordanian Black Hawk helicopters first to capture the motion of a real helicopter in flight as well as the interaction with dust in the environment. The visual development team at Framestore built 3D models of Osama Bin Laden’s secret Abbottabad compound for Hindle before the production design team dug in and spent three months building a full-scale replica of the compound out of aged cinder block. “We had to build the compound so that it could withstand real Black Hawk helicopters flying right down on it, so we built the structure on six-to-nine-foot caissons underground,” said Hindle. Even though the stealth helicopters used in the film’s climactic sequence were CG, VFX 10 Most of the raid was shot twice — once night-for-night, and a second time with a “night vision” lighting scheme that sought to replicate what the SEALs would have seen during the actual event. “We did that by wiring up a series of infrared lights, and then making them film-friendly. This turned out to be pretty accurate to what SEALs see because they also have mounted infra-red lights,” said Fraser.

This article is reprinted with permission from StudioDaily.com.