30 minute read

In Memoriam – Gordon Willis asc

Douglas Kirkland

Gordon Willis,

asc, 1931-2014

Gordon Willis, asc, a cinematographer who had a seismic influence on his chosen art form, died May 18 at age 82 in North Falmouth, Mass. The cause was complications from cancer, according to his son Gordon Jr.

Best known for the dark chiaroscuro he brought to Francis Ford Coppola’s Godfather trilogy, Willis also enjoyed numerous collaborations with Woody Allen, including Annie Hall, Manhattan, Zelig and The Purple Rose of Cairo; and Alan J. Pakula, including Klute, The Parallax View, All the President’s Men and Comes a Horseman.

In a profile of Willis that was published in The New Yorker in 1978, Pakula said, “Working with him is collaboration at its best. It’s a joy, it’s fun, it’s camaraderie — like being kids and playing after school. They say about certain film editors that they have ‘gifted fingers.’ Gordon has that kind of eye.”

“In an industry that more often than not celebrates mediocrity over true genius, Gordon Willis occupies a category separate from and above all others,” ASC President Richard P. Crudo said. “He stands beside Griffith, Welles, Ford and maybe a few others as one of the industry’s great originators. Just as those men did, Gordon not only changed the way movies look, he changed the way we look at movies. influence,” Crudo continued. “Along with Conrad Hall, asc, and Owen Roizman, asc, Gordon Willis helped obliterate all that was traditional about the way films were staged and lit — ‘mounted,’ in Gordon’s words — and he then ushered in a new freedom that subsequently enabled most every look and texture that we now take for granted in cinematography. This is a momentous loss. If it’s safe to say there will never be another Rembrandt, I have an even safer bet for you: there will never be another Gordon Willis.”

Willis received the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 1995. He earned two Academy Award nominations, for Zeligand The Godfather Part III, and the Academy honored him with an honorary Oscar at its inaugural Governors Awards ceremony in 2009.

In accepting his honorary Oscar, Willis called his career “a series of great encounters, and they have been an embarrassment of riches. I’ve always had an opportunity to do what I want, the way I want, and I’ve always worked with people [who] have given me that opportunity. In retrospect, I think probably every good thing that’s ever happened to me has happened because of another person. Fifty-four years ago, I met this darling girl and married her. We’ve had three kids and now five grandchildren. And along the way, I met this remarkable group of directors, producers, very fine actors and very fine technicians who extended themselves for me. I couldn’t ever really give them back what they gave to me. I had the best of it.”

Willis is survived by his wife, Helen; two sons, Gordon Jr. and Tim; a daughter, Susan, and five grandchildren.

Reprinted with permission from the American Society of Cinematographers. American Cinematographer will publish a tribute to Willis in its October issue.

CSC Member Spotlight Brendan Uegama

csc

Credit: Kyle Cassie

What films or other works of art have made the biggest impression on you? Apocalypse Now for its mastery on so many levels. Baraka for its power and beauty. And Return of the Jedi for being the first film that made me look at films as a filmmaking process made by people.

How did you get started in the business? I’ve always had a passion and interest in image making. I started making extreme sports films and was lucky to shoot with some of the world’s top freestyle motocross riders, skateboarders and snowboarders. I then got into lighting and went to study cinematography further at Capilano. It quickly became my life passion.

Who have been your mentors or teachers? I have had many mentors in different ways, however, most prominently Jack Green asc. He took me under his guidance for a summer in ’06 and we’ve stayed in contact to this day. Another mentor has always been Ross Kelsay my teacher at Capilano who believed in me and pushed me from the start.

What cinematographers inspire you? Vittorio Storaro, Roger Deakins, Christopher Doyle and Conrad Hall to name a few.

Name some of your professional highlights. The most important project is always the current project, and each film or commercial I do is a highlight. What is one of your most memorable moments on set? The first time I shot a project on film and watched the dailies.

What do you like best about what you do? I love the limitless possibilities of cinematography. Creativity is endless if you and the team you’re on set with believe in the film and the power it can have.

What do you like least about what you do? When others around you do not care for the shoot and are only there for the pay cheque.

What do you think has been the greatest invention (related to your craft)? It may not be my favorite, however I feel the greatest invention in cinematography is the high quality digital cameras we are mostly working with today, as it has transformed the industry worldwide in just a few short years.

How can others follow your work? Visit www.brendanuegama.com and follow my Instagram at instagram.com/bmkuegama

Selected credits: Exit Humanity, Blackburn

Vic Sarin csc

Follows His Heart for

The Boy from Geita

By Katja De Bock, Special to Canadian Cinematographer Photos by Sepia Films

When director-cinematographer Vic Sarin csc was researching his 2013 documentary Hue: A Matter of Color about the issue of colourism (discrimination within an ethnic group towards people with darker complexions), he conducted interviews with people all over the world who had been bullied because of their skin tones. In the process, Sarin – who was born and raised in Kashmir, India – came across the story of a recent development in Tanzania, a country with the highest rate of albinism relative to the entire Sarin worked to gain the trust of the local children while filming population. Albinism is a nonThe Boy from Geita. contagious, genetically inherited condition resulting in a lack of pigmentation in the hair, skin graphic footage of children with chopped off limbs and deand eyes, causing vulnerability to sun exposure and bright cided to follow his heart and make a feature length documenlight. Albinism is rare in North America and Europe, but in tary about the subject. Tanzania, and throughout East Africa, it is much more prevalent, with estimates of 1 in 1,400 people being affected, acTo his astonishment, he found an activist practically on cording to Dr. Murray Brilliant, an American geneticist who his doorstep in his hometown of Vancouver. Peter Ash – a did a DNA sampling in Tanzania. Canadian born with albinism – was raising money through his charity, Under the Same Sun, to help 12-year-old TanWitch doctors in the region, trying to make a buck in a clizanian Adam Roberts, who lost several fingers and the use mate of economic growth, proposed that a drug made of alof both arms due to an attack provoked by his own father. bino bones could lead to prosperity, and so set in motion an Ash convinced Vancouver General Hospital staff to donate unprecedented murder spree. Sarin found locally produced their time to try and save Adam by means of a challenging

Albinism is rare in North America and Europe, but in Tanzania, and throughout East Africa, it is much more prevalent.

operation, which would have a toe removed to replace his missing thumb. Adam became the main subject of Sarin’s documentary The Boy from Geita.

From all the cases he could have followed, Sarin chose the story about Adam, not only because of the Canadian angle, but also for his point of view as a storyteller: “In all my films, I do take an issue, but I also like to give someone hope at the end. Without hope, what’s the point,” says Sarin, who wanted to show both sides of the issue. While making The Boy from Geita, Sarin found that there was a perception by the locals that people with albinism are ghosts rather than real people. Echoing a local teacher in his film, Sarin says, “The biggest problem in Africa is ignorance.”

Sarin made a series of visits to Tanzania with two camera operators. They travelled light, taking minimal gear, including two SONY EX3 cameras, which Sarin owns. Though the model is now discontinued, Sarin says he is still happy with his SONY. The portability of the small camera is a great advantage, especially when filming an issue like the murder of children. Sarin and his team intended to move about like tourists and avoided raising unnecessary attention. They only used a tripod for sit-down interviews and did not bring additional lights. Sarin operated the camera himself for most of the cutaways, second unit footage and the operation sequence at VGH.

Noting that the look of a documentary is often driven by the subject of the film, Sarin knew that being such a sensitive subject, it was important to not impose any photographic design when shooting The Boy from Geita but rather to let the subject of the film take him wherever it was necessary. Still, he felt that the story needed naturalness and honesty in the camera. “Going in, I knew the camera had to be invisible,” he says. “Fortunately, with digital technology it is easy to do so. I felt the camera should be used handheld without much fanfare as far as the lenses, filters and lights go, except for the interviews.”

The choice to just rely on the standard SONY EX3 zoom was a conscious one. “For the effectiveness of the story it was important that the final image is consistent and perhaps even not that high quality or resolution, therefore maintaining the honesty and real quality of the story,” the cinematographer says.

As people with albinism are very sensitive to direct light, Sarin tried to avoid shooting them in bright sunlight as much as possible and did not use additional lighting. “This ‘handicap’ of people with albinism I had to respect,” Sarin says. “Fortunately, them being so light, this self-imposed restriction wasn’t that difficult. Having no lights also helped to keep the natural look for the story.”

Since the contrast was so great between the people with albinism and the other African subjects in the story, Sarin avoided as much as he could having both of them in the frame. On these occasions, as well as when shooting in darker locations, he sometimes used a white towel as a small bounce board,

just to give some detail in the blacks. “After a while people in the villages got to know me a little, so consequently I was able to make some slits or widen natural light sources, [such as] through a window or door in their huts,” the cinematographer says.

Aside from the logistics of filming, Sarin had the task of gaining the trust of the local people, made more complicated by the fact that he did not have the blessing of the local government and was posing as a tourist. “I just followed some of the characters for a short time without shooting anything, just to get them used to seeing me around with a camera hung to my shoulder,” he explains. “I had to follow the schedule of the characters and not mine. It was important so that they were not conscious of my presence and the camera.”

Getting his main subject to open up was perhaps one of Sarin’s biggest obstacles. “Going in, I knew it was going to be difficult to gain the trust of the children, but I was so sure that with time I would have it. Well, that didn’t quite happen, partly because of the language, but also, it is a horrible nightmare – who wants to talk about [that]?” Sarin says. “I had many sessions with Adam to tell me his side of the story, but each time I tried to talk to him on camera he just wouldn’t say anything or have any focus. Since I don’t use any narration in my documentaries it was important that he tell me what happened. Without his telling me I had no film. I understood his pain, so I tried various paths to get to him. I was almost going to walk away defeated, except for one final try. I got a little angry and I mentioned to Adam perhaps he is hiding something. Well, with this accusation he opened up.” Among the things Adam revealed is that his own father gave a neighbor permission to attack him with a machete, resulting in the loss of some fingers and a thumb on one hand and large pieces of muscle on the other arm, making it virtually impossible for the boy, who loved drawing, to use his hands and arms.

As Adam finally told his story through a translator, Sarin kept the camera as far back as he could, “so that the little boy was only conscious of me talking rather than the camera,” he explains. “He tells his own story, so simple, without pathos. The simplicity of that is to me the beauty of this film.”

Sarin is also confident with the quality of the exhibition copy. He won the 2013 CSC Robert Brooks Award for Documentary Cinematography for the camel-racing themed Desert Riders using the same SONY EX3 and he loved the visual quality of Hue on Vancouver International Film Festival’s large screen.

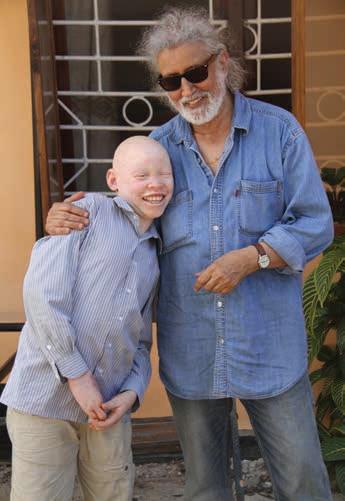

Since completing The Boy from Geita, Sarin has not stood still. Feeling perfectly at ease wearing two departmental hats,

Vic Sarin csc and Adam Roberts

he has meanwhile shot and directed the Lifetime/Movie Central/The Movie Network TV Movie A Daughter’s Nightmare in Kelowna, B.C., using drones to film breathtaking establishing shots of the Okanagan Valley.

For his latest project, The Keepers of the Magic, Sarin is travelling around the globe to interview the world’s most famous cinematographers such as Vittorio Storaro (Apocalypse Now, The Last Emperor) and Gordon Willis ASC, who shot The Godfather trilogy, many of Woody Allen’s films and recently passed away. In this magazine a few years back, Sarin said if he could, he would shoot everything on film. “I still do,” he says today. “In film I had a very strong discipline. You had to be sure what you wanted to do. The flip side of that was the discovery. There was always surprises, and I loved the surprise element. I think that is no longer available in digital photography as the image is right there.”

The Boy from Geita premiered this year at Hot Docs in Toronto, was licensed by Super Channel and will be shown on the pay TV channel this autumn, and subsequently on CBC. Peter Ash’s charity Under The Same Sun intends to use the documentary in an ongoing awareness and media campaign on the ground in East Africa.

A master class at the IAGA.

IAGA 2014: A Greek Odyssey

Delphi, Greece, steeped in its antiquity and its folklore, was the perfect setting for the 2014 IMAGO Annual General Assembly (IAGA), and as the CSC representative I was very happy to be there and watch a bit of history in the making. IMAGO is an umbrella organization for 47 cinematography societies from around the world. Its goal is to promote professional cinematography, to vigilantly lobby for cinematic authorship rights and improve the general working conditions for cinematographers. IMAGO is comprised mostly of cinematographer societies from Europe with full member status, since its origins are footed in the European Confederation of Cinematographers. Non-European societies were all associate members until this year’s IAGA, and this is where the historic aspect kicks in. To loud applause, and I do believe a few whoops, IMAGO ratified changes in its statutes, allowing for the first time non-European societies to become full members with voting rights. The first to step up and receive full membership, ushering in a new era for IMAGO, were the Australian Cinematographers Society (ACS) and the New Zealand Cinematographers Society (NZCS), while the Japanese Society of Cinematographers ( JSC) and the Israel Association of Cinema and Television Professionals (ACT) are in the wings completing their

By Joan Hutton csc

Photos by Louis-Philippe Capelle sbc

applications. As for the CSC, it is still the status quo as an associate member of IMAGO, although a motion was passed at the CSC 2012 Annual General Meeting for the upgrade to full membership once the mechanism to do so was in place with IMAGO. The motion sits now before the CSC Executive for deliberation.

When I started in the film business back in the early 1970s, women cinematographers were virtually non-existent, but through the years our numbers have grown to the point where it’s not all that uncommon anymore to see a woman behind the camera. At previous IAGAs, I could usually count myself and two or three other female delegates in attendance. However, 2014 proved to be a banner year with nine female cinematographers as delegates at this year’s IAGA. It is heartwarming to see women cinematographers making an inroad at the international level, and I do hope the number continues to spiral upwards.

Moving away from the official discussions, the background buzz at the IAGA, which was when two or more cinematographers spoke casually with each other, seemed to always gravitate towards the role of the cinematographer in the digital age.

The ones in which I participated were anxious conversations, questioning the diminishing stature of the cinematographer in today’s production hierarchy and the future relevancy of cinematography in a world of constantly changing technology. Uneasy questions with no easy answers. In the new digital reality, most agreed that cinematographers need to be on a continuous learning curve, reinventing themselves, but it is the person, not the tools, that shape the shot and create the look of a film. While the future of cinematography is not etched in stone, DPs like Academy Award-winner Emmanuel Lubezki asc have shown us where it can go with his groundbreaking work on the space disaster film Gravity. Pushing existing technology beyond its cutting edge and even inventing new technology for the film, Lubezki pondered whether or not anyone thought what he did was cinematography, algorithmography or whatever, but opined that it still required a cinematographer, a person overseeing the images. It doesn’t happen by itself. I think it is fair to say that Gravity would not be the cinematic marvel it is without Lubezki’s creativity.

An interesting topic on the IAGA agenda tackled the supposedly unassuming subject of film archiving and restoration, which proved to be anything but that and inadvertently questioned the relevancy of cinematographers. IMAGO is very active in promoting cinematographer authorship rights, a concept that views cinematographers as the co-authors of the images they create. This puts them on equal footing as producers, directors and writers, legally and morally, and opens the doors for residual compensation. The concept has taken hold in several European countries, most notably Poland, where cinematographers have legal standing, but it is an uphill struggle. As far as North America and the rest of the world is concerned, cinematographer authorship rights Christian Berger aac at the IAGA. are non-existent and only talked about in hushed conversations as a non-starter. For Canada, I’ve been told that there could be legal grounds for cinematographer authorship, but I’ve never seen it enacted. The only cinematographers I’ve ever known to receive residuals are the ones who are also producers of their own films.

So what has this got to do with film restoration and ar

Science of the Beautiful

SALES SERVI . CE RENTALS . HDSOURCE.CA // 905 890 6905

chiving? Much of the world’s celluloid film has yet to be digitized and archived. In Europe, around 98 per cent of the film legacy is languishing in film cans, in vaults or in worse conditions. Last year, IMAGO endorsed a film restoration and digitization process devised by the Association of Czech Cinematographers (AKC) called Digital Restoration Authorizate (DRA). The DRA method requires that a film’s original cinematographer, if they are capable and still alive, be a part of the restoration and digitization process. If not the original cinematographer, then at least one or preferably two other cinematographers become part of a process. The premise being that who else but cinematographers, the co-authors and creators of the image, would be able to best replicate the true look and feel of a fellow cinematographer’s film.

When the DRA method was presented to international and European archival organizations, it fell flat. The archivists said it was unnecessary, too cumbersome, too regulation heavy and too costly. But most interesting of all, it was felt that the job of a cinematographer was to shoot films and nothing more. No latitude is given to cinematographer co-authorship of films in the preservation process even on a logical and moral level. IMAGO responded by distancing itself from the DRA initiative, and at the IAGA a vote was held to dissolve the existing Author’s Rights committee in favour of forming a hybrid Film Heritage and Author’s Rights committee, which as the name suggests, will deal specifically with restoration, archiving and author’s rights. This new committee will approach the archivists to find a common ground to move forward on restoration and archiving of films that includes cinematographers in the process. I’m keeping my fingers crossed that IMAGO and its new committee is successful on this issue that strikes to the very core of being a cinematographer.

Group photo at IAGA 2014

At this writing, the location for the 2015 IAGA has not been established, but the frontrunners for hosting countries seem to be Russia and Israel.

Left: Haris Zambarloukos bsc at the IAGA. Right: Phedon Papamichael asc gac at the IAGA. Bottom: Delegates at IAGA 2014, including Joan Hutton csc (centre).

Warren shot stills and video with the Canon 5D Mark III.

There is a big map of the world in my office, and on it are dozens of push pins that indicate where my journeys have taken me in my 30-year career. There has always been one big continent right in the middle that has nary a pin prick: Africa. I don’t know why, but it was never at the top of my bucket list. I may have thought it a little intimidating. But then an opportunity came up to travel to Tanzania. My old friend from CTV, Scott Hannant, was producing a series of

My East African Adventure

Words and photos by Peter Warren csc

videos for the Aga Khan Foundation that would focus on its work with education in that region. This was just too good to pass up.

The first thing I do is contact my buddy Mike Grippo csc, who has done a lot of work in Africa. “Mike, I’m going to East Africa, what do I need to know?” I ask. “Bring a flashlight,” he says. “And make sure it’s the headlight kind ‘cause you’re going to need it when you go to the washroom at night.” This,

amongst all the other valuable advice he gave me, was the most salient. Number one, electrical power is not a given in Tanzania. And number two… Well, you will be doing lots of number twos.

I decided to shoot these videos with the Canon 5D Mark III. The great thing about the 5D is that it doesn’t look like a video camera, which makes customs so much easier. With the 5D and a tacky floral shirt, you are just another tourist. It also means that you can travel lighter. My tripod for the 5D weighs about 10 lbs, and I created a lightweight dolly for this shoot that came in at about the same. But the main reason I went with the 5D was that the client also wanted me to take stills.

I assembled a complete battery-operated LED lighting kit for the trip, consisting of a 900, a 600 and a 250. With the difference in power cycles in the PAL regions, I did not want to go with practical lights. The LEDs covered virtually every situation. When I shot interiors I turned off all the practicals and used my lights to complement the daylight; night scenes were well covered with these three lights as well. In fact, in the daytime I could place the two larger lights outside windows in small huts and classrooms to give direct light. The 900 and 600 are amazingly powerful outside. On overcast days they worked as a key, and on sunny days they performed well as fill, but they have to be in pretty close. A side note: the 250 is amazing when shooting interior car scenes during the day. I suction cupped it just below the mirror, and it provides a constant exposure on the face. And with the 5D being so small I can put my back against the dashboard and get an almost full frontal of the driver with my 16-35 mm lens. Just don’t tell Health and Safety. The lights all fit in one lighting kit with five stands, a reflector, various CTO/CTB gels and 216, and amazingly it all came in at under 50 lbs. So my luggage amounted to one lighting kit, one tripod case and my personal suitcase, which was packed with two-thirds gear, one-third jammies and underwear. The camera and lens were my carry-on. I should mention the crew for this shoot amounted to me, myself and I. Tanzania: what an awesome, inspirational, humbling and challenging place. There are a billion award-winning photos just waiting to be taken. But taking them can be quite a challenge. In the major centres, which are crazy with activity and colour, I was yelled at within seconds of pulling out the camera. They assume you are there to exploit them, take pictures, and sell them for profit, while they get nothing. Apparently, there have been cases where unscrupulous people have set up fake charitable foundations using video and stills, only to

pocket all the donations themselves. How can I explain to them that we are legitimate? You can’t. You ignore the jeers, hope nobody approaches with a machete, roll for 30 seconds, get back in your vehicle and drive off. In the villages, people are not as aggressive, but they do expect to get some stipend for taking their photo – what amounts to a dollar. You can call it unethical, but it is the reality, and honestly, I did not mind paying.

Having said all this, the people of Tanzania are so

A couple of innovations worth sharing:

Imade a dolly for this shoot that is essentially a high hat with wheels. I actually bought a second tripod and sawed the legs off. Believe it or not, this was cheaper than buying a proper 70 mm high hat bowl! The 5D is so light that you can buy a good fluid head tripod for under $150. The dolly track runs between two light stands. I used 2x2 wood that sat on top of the light stands to support the track. I just drilled a 5/8th hole in the middle of each piece and inserted a thumbscrew, then notched the surface to hold the metal rails. The track is 3/4” steel rod. I had four, 4-foot sections that screwed together so that I could dolly 8 feet; the four sections fit in my tripod case. Between the two light stands, I could go from 3 feet to 6 feet in height, but I also found it most useful on the ground to get low-angle dolly shots.

Peter Warren csc travelled to Tanzania to shoot videos portraying the Aga Khan Foundation’s work in education.

unbelievably friendly and warm. The rural areas are stunning, a photographer’s dream, with small mud huts and grass roofs, patchwork fields set against a huge blue sky and lush green mountains in the distance like a watercolour painting. But the façade belies the reality. These people are desperately poor. Children go to school hungry; sometimes the only nourishment for dinner is a cup of tea. And yet I was told there is a saying here that you never let your neighbour go to sleep hungry. This is truly a community. They look out for each other and yet they are only a drought away from starvation.

After flying from Dar es Salaam – Tanzania’s largest city – to the southeastern municipality of Mtwara, we meet our driver and load up to travel the four hours to the small village of Nachingwe. About an hour into our drive, at speeds of up to 130 km on roads that back home would not merit an 80 posting, I start contemplating that maybe kidnapping, gun toting thieves and terrorists should not have been at the top of my greatest fears list. A simple, horrific, fiery car crash may be the way I leave this planet. How ignominious! After surviving hours of dodging pedestrians, motorcycles, bicycles and goats, we finally hit the unpaved, beautiful red dirt road that would lead to our first village.

In Nachingwe, the poverty is so apparent but so too are the smiles of the children and adults alike and the genuine warmth and friendliness of all. As we slowly drive through the village (only because the condition of the road precludes our driver from hitting Mach 2), a simple wave and smile is returned in kind with enthusiasm and more than a little curiosity. After meeting all the officials, we finally get to start what we have travelled over 10,000 km to do – tell the story of the children and their struggle to get a decent education.

In the Classroom When we are introduced in the classroom of five-to-nineyear-olds, they are quick to jump to attention and welcome us with a well-rehearsed greeting in perfect broken English. Their surroundings are barren; the mud walls are worn and weathered. The small windows let in daylight and whatever breeze happens to blow by. Today is moderate, maybe 25 degrees, but I can only imagine what it’s like during the hot season or the rainy season. There is no electricity, no running water. Toilets, if they have them, consist of a small room with a hole in the ground, no toilet paper.

As the class begins, the enthusiasm of the teachers is infectious, the children are laughing, eagerly raising hands, singing rhythmic responses that acknowledge correct answers. My work is easy, I have set up lights outside to boost the level of daylight, kept both lights to one side so there is lots of contrast and then I just roll. I start with some dolly shots, back of the room, then from the side. Using the 24-105 mm I’m able to get wide establishing shots and tight shots without a lot of fuss. Then I ditch the dolly and just get in there and shoot, down on my knees, tight smiling faces layered three deep, pop on the 200 mm to get pencils hitting the paper, tilt up to capture the concentration in their eyes. The last thing

Warren fashions portable water sandbags. Opposite page: Warren’s custom-made dolly.

I do is throw on the 16-35 mm just to try and capture the essence of this space, the dirt floor, the little windows, the tin ceiling and all the children crammed into a space designed for half their numbers.

Outside in the playground things are a bit more challenging. As I set up to take a shot of kids kicking around what looks like a ball – it might be rags tightly bound – one child notices the camera, then two, and before long I have a virtual wall of smiling young faces staring right down the lens blocking any possibility of a shot I might have had. They are immensely curious and love having their picture taken. So I throw on the 200 mm lens, shoot from as far back as possible and keep moving from one side of the building to another which gives me about a minute or two to get a shot before the wall of smiling faces reappears. I have shot all these same shots hundreds of times back home, but there is just something magical about these. Maybe it’s my own inexperience with these types of surroundings, maybe it’s the beautiful earthy tones of the dark skin set against worn sandy walls and vibrant red dirt. Children playing on the green grass made lusher by the rainy season.I can’t help but overshoot all of it.

This is just the beginning. Over the next 16 days, we shoot life around the village: young children managing herds of cows and goats; women carrying babies on their backs and water, grass, dried fish, and even bundles of wood on their heads. Every time I turn around there’s something to shoot. What is most inspiring is going home with a couple of the children and getting a glimpse of how they really live. We go home with nine-year-old Acidiri, who wants to be a pilot when he grows up. Mom and Grandmother happily invite us in. I suddenly feel an overwhelming feeling of guilt when I realize their home is no bigger than the smallest bedroom of our comfortable suburban house. As meagre as it might appear, they clearly have a great sense of pride – the dirt floor all around the hut has been swept clean, the small subsistence garden is well tended, and there are little flower gardens that frame the front entrance. But what’s missing is so apparent: there is no running water, no electricity, no table to eat meals. This is life in the rural villages. But there is also no shame, no attempt to make us feel sorry for them. They eagerly prepare a meal, and I start shooting.

Scott and I made it back, although my tripod case got crushed by KLM. But I am so glad that I had this opportunity. It is the most amazing thing about our job – that we get to become so immersed in people’s lives. I will forever be humbled by this experience and will never complain about a missed meal again!

A video essay of Warren’s experience can be found at www.peterwarrendop.ca and subsequently on the Aga Khan Foundation website akdn.org.

The other thing I came up with that worked extremely well is portable water sandbags. Go to the camping section at Canadian Tire and buy 8-litre dry sacs; they are yellow and cost about $10. Then buy large, double-zip Ziploc bags; each dry sac will take three. When you arrive at your location you can fill the Ziploc bags with water – don’t try to overfill them – and then just seal them up and place them in the dry bag. Close the dry bag, squeezing the air out, and presto, you have a 15 lb sandbag. Even if the Ziploc accidentally opens, no water will escape the bag. You can also fill them with dirt, sand or rocks depending on your location. The neat thing about the dry sac is that you can clip it around your light stand. Works like a charm and takes no room in your case! (For more of Peter Warren csc’s innovations, see “The Adventures of a Serial Inventor,” Canadian Cinematographer, February 2014).

VANCOUVER CALGARY VANCOUVER CALGARY 604-527-7262 403-246-7267 604-527-7262 403-246-7267

TORONTO TORONTO 416-444-7000 416-444-7000 HALIFAX HALIFAX 902-404-3630 902-404-3630