11 minute read

Cams Part 2

By GEORGE WILLIS csc, sasc

Stick a camera on pretty well anything and you have some sort of “cam.” It can be as simple as attaching a rope to the top handle of a camera for a “Ropecam,” “Swingcam” or a “Danglecam.” You pick the name. At the other end of the spectrum are custom rigs with price tags into five

figures. No matter the cost or sophistication, rigs exist to provide those extra special shots we crave as cinematographers. What follows are three cams that I designed and built for those one-of-akind shots. I might add that these rigs were built before digitization and the ultimate cam, the GoPro, was invented. I love wood, PVC (polyvinyl chloride) and aluminum! They’re my favourite materials for building rigs. Being easy to use and machine, plus the option of immediate modifications, made them my construction choice for the “Woodcam.” With the camera almost always a couple of inches off the ground, the shot was to take off at a trot across a street, mount a sidewalk, jump a 2-foot hedge, cut across a lawn with the sprinkler going, as a ball gets kicked from under the lens, down a small rockery, over a child’s wagon, through a garage, out a back door, climb four steps into a house, with a sharp 90-degree right turn into a kitchen, across a floor and up to the refrigerator freezer door at 5 feet. All in one take please! My first thought was to call one of those super-fit Steadicam guys who can make the camera “float like a butterfly.” But I had confined spaces and tricky turns to deal with, and this was definitely not Rocky with Garrett Brown running up the front steps at the Philadelphia Museum of Art with loads of room to maneuver. Nix the Steadicam. I then figured that with the shoot a week away, I could learn to run and breathe over a long sustained period of time while holding about 30lbs in my right hand or I could pass the job onto an up-and-coming marathonrunning camera operator built like Arnold Schwarzenegger. Both these ideas of course were more comical than they were ever practical. My solution was a bit of trial and error. I started by cutting two pieces of ¾” medium density fiber board and connected them with four threaded rods. I now had a basic “cage” in which to mount the camera, a bare bones ARRI III with a 200-foot magazine. Someone suggested that I use a 400-foot mag to get more takes per roll, and he wasn’t

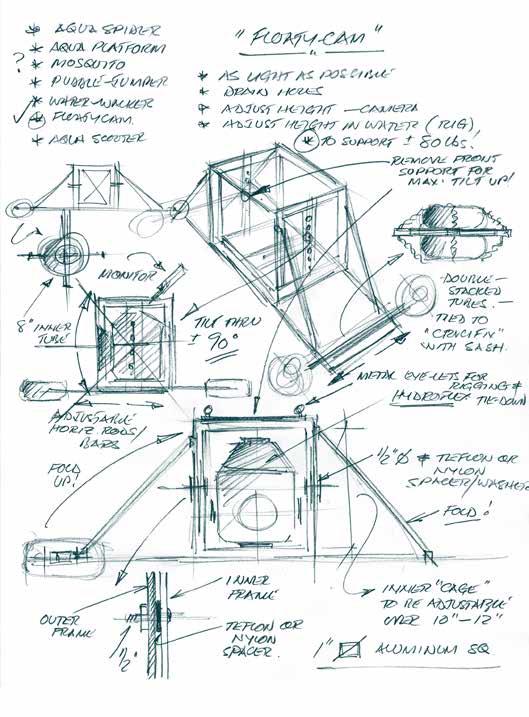

kidding! I mounted a wide-angle 14 mm lens to the body, along with a basic motorized focus and a custom-made French flag. Framing the shot was going to be a problem, so I mounted a small video recorder/monitor to the rig. So far so good! After initial tests, a small gyrostabilizer unit was added to steady the rig on the horizontal axis. Also, because the rig was mere inches from the ground, a “skid-plate” was attached to protect the lens from damage. Just as I began to joyfully think that this strange assembly might just work, I realized the Woodcam needed an auxiliary handle of some sort so that I could raise the rig 5 foot at the end of the shot. After all, this was no Steadicam. The answer was to add a “grab handle” onto the basic frame to assist in lifting the assembly up to the freezer door. In theory, the construction of the Woodcam was relatively simple, but in practice I was jolted by a rude realization – the thing weighed a ton. I could barely lift it, yet alone run with it onehanded! Off with the French flag, lens flares are kind of cool! Off with the gyro unit, nobody would care if I developed a hernia anyway. Bring on the smallest and lightest weight video monitor that I could find and try again! I also had another little problem to do with the 14 mm lens. If I took big steps, my running shoes came into frame. The obvious solution was to take smaller steps, which we did. Guiding the Woodcam while the first assistant pulled focus and the grip carried the batteries, we ran in mini-step unison, almost on our tiptoes all tethered together by the umbilical power cords. It took 14 takes to get it right, and we were not exactly a pretty picture running in short lock-step, but it all worked out well and the Woodcam was very much worth the effort. standing at the edge of the The Floatycam railing on deck. The distance from the deck to the water is about 50 feet. The shot calls for the camera to follow the action as the figure falls towards the camera and splashes into the water, holding the end frame solidly. Hmm… Not that easy of a shot. First of all, the camera operator must be able A couple of years ago, the small foldto follow the action with the camera in up kids’ scooters were all the rage, and I the water, as a stunt person falls 50 feet thought it might be fun to rig a camera and splashes down about 3 feet in front to one of them for an upcoming (kids’ of the lens, and the final frame must drink) commercial. I bought a scooter be partially submerged. Secondly, the and did some basic modifications to crew is floating in ice cold, 30-foot deep strengthen the chassis, but most of the water, holding onto a camera and wawork went into building the camera terproof housing weighing 90 pounds. mount out of PVC and aluminum. RiIf that’s not difficult enough, the progidity was required to hold and stabilize duction is also budget challenged, so an ARRI 435 and the “Scootercam” was there is no money to rent a Hydroflex born. The mount could be adjusted to Aquacam with remote head, let alone face the front or the rear of the scooter, a medium-size crane arm mounted to the idea being to keep the small wheel a barge or floating platform. A not so in frame, so that the viewer would know easy shot has now become a very difthat the camera was actually sitting on ficult one. a scooter. The main requirement, we So how does one float the camera in soon discovered, was that Scootercam, a locked-off position, operate and then because of the small diameter of the hold a rock-steady end frame with no wheels, had to run on a smooth surready-made technology? Enter the face. I added a counter-balance and an much cheaper “Floatycam.” outrigger wheel on one side to keep Here’s how I built it. At my local dive the camera clear of the pavement and store, I consulted with a dive buddy to harm’s way. Additional rigging was reestablish the float-to-weight ratio for quired to secure a small monitor on the this particular situation. I then took handlebars to act as a viewfinder. I only my design to Filmair, the company that used the “Scootercam for one shoot, built the “giraffe” crane, and had them but it was great fun to design and build! weld a framework out of aluminum. A Being an underwater cinematogralittle heavy, but this was the best mapher and operator, I was called to disterial for the rig. The framework concuss some second-unit shooting for sisted of two cubes, with the ability of a feature. The producer said it was a one cube to rotate within the other, to fairly simple night scene shot, where provide the camera tilt for the follow the camera, with a wide-angle lens at shot. Attached to the outer cube were water level, shoots up the side of a ship two sub-frames that hinged down and at harbour. The ship is painted black locked into position almost like wings. and is silhouetted against an almost The camera sits on a platform within black sky. The camera frames up on a the smaller of the two cubes, which is figure dressed in light-coloured clothing see Cam page 22

Credit: Phots courtesy of Cinéfilms & Vidéo

man.” And I put the film on the projecCams from page 21 adjustable in height. This will determine how far in or out of the water the camera lens will be placed. With the camera in place, the entire rig weighed close to 150 pounds and it still needed to float on the water surface. A floatation test combined with some rudimentary math allowed me to arrive at what kind of equipment would be required to keep this monster afloat. A trip to Canadian Tire resulted in the purchase of eight small inner tubes that were attached to the rig via some crucifix-shaped adjustable arms. These, in turn, slid into brackets on the main frame and provided the necessary buoyancy, which could be adjusted by varying the inflation pressure. Once again, it all sounded great in theory, but I wasn’t able to test Floatycam until the night of the shoot, which became a “do or sink” situation. Shooting black on black is fun at times, but certainly not at night in a harbour, in water at around 10 degrees Celsius, with oily fumes wafting through the air. a month, and I became assistant to some of the greatest filmmakers who ever walked on this earth.

On the film business:

If you come with a Roger Racine csc, right, date unknown. project, a real, wonderful great project, the first Racine from page 6 question they ask is, “Will it make monadministrator at this time. I said, “I’m me the first question we should ask is, very much interested in film and I “Will it make a good film? Will it make heard that you’re looking for posia film that will stay part of what our tions.” The funny part of the story is descendants will see in 50, 100 years?” that John Grierson came out of his ofThe film business is a business, yes, fice, with his Scottish accent, and he but it’s got to be more than a business. says, “Well, show me those films, young Without substance it’s nothing. tor, and he looked at maybe 10 minutes, On the power of film: and he said, “This young man seems to Film is one of the greatest instruments have some talent, give him a job.” So for communication. It shouldn’t be MacLean hired me at the salary of $60 used just for selling chocolate bars, it

ey at the box office?”It hurts because to Floating in the water and looking up at the ship certainly put a new light on a situation – with very little light. The first challenge was holding the very specific frame steady while avoiding flares from the lights. Trying to hold position in the water during and after the stunt action in a slight breeze proved to be impossible. Without an anchor we were drifting all over the place. That’s it, an anchor! We tied a sash to the rig, and sandbags were attached to the sash cord. Standby divers then positioned them on the murky bottom of the harbour channel. This took some time, because the “anchors” needed to be constantly reset until everyone was satisfied with the framing. Okay, here we go, this is it. Frame the shot. Where the heck is the stunt person? Oh, there he is, the light speck in the completely black frame. “Stand by, roll camera.” Oh no, the frame is even darker with the mirror spinning. “Action!” Got him, got him. Well, not quite. We discovered that even while the video camera and monitor should be used for education, it should be used for culture, and it should be used for getting people’s minds better, not just their stomach, not just their body. Because take the mind away [and] we’re just a gorilla, you know?

On his hopes for Canadian cinema:

I think that Canada as a country will have to find its own soul and its own directors and writers and so on. And I hope I live long enough to see that. I would be a very, very happy person.

On last year’s screening of his film Ribo ou “Le Soleil sauvage” for the first time in North America at Montreal’s Cinémathèque québécoise:

The only thing I have to say is thanks for coming. Our profession is a means of communication, and when it’s non-communicable it is no longer cinema.

had been adjusted to allow maximum brightness, the external LCD monitor was not showing enough clarity for perfect framing. The solution was to “jury rig” an old-style black-and-white tube monitor that allowed the definition we needed. The monitor sat in a small boat floating next to the rig. As difficult as the situation was, as I had to look at the monitor set at almost 90 degrees to the camera, I now at least had a very good image and the next take was perfect. Chalk one up for the Floatycam. The rigs that I have built during my career have added enormously to the creative side of filmmaking and made my professional life more interesting as a result. The best part of the process for me is the challenge and then devising a viable solution. The next best thing to designing is when I got to actually build them myself.

Have you designed and built your own rigs? Do you have pictures or diagrams? Canadian Cinematographer would love to hear from you about your inventions. Email: editor@csc.ca