20 minute read

Tech Column

Credit: Alex Mead

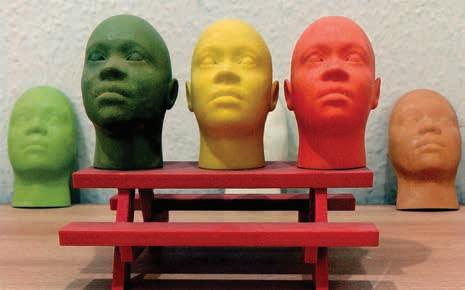

Cinema,” famed filmmaker Jean“ Luc Godard is credited with opining, “is the most beautiful fraud in the world.” PRINTING 3D Makes the Unreal Real

A “gold-plated” version of the James Bond’s classic 1964 Aston Martin DB5 prop made from 18 3DP parts sold at Christie’s. Indeed, cinematography sometimes seems to be about making the unreal seem real and the real seem unreal, blurring the lines between truth and deception in telling a story. Lighting, lenses and framing dance with scripts, actors, movement and vision but let us not forget the other elements in the scene, the costumes and the locations. Of course, these days everything done in the flesh can be done artificially. Mechanical sharks, CGI-created terminators and green screens have all made the impossible possible, the unreal real. Toronto has a proud legacy of digital effects, stretching back to Alias Research in 1983, which later became Alias Wavefront before being merged into Autodesk in 2006. Maya, its 3D modelling software, was state of the art when it launched in 1998, winning an Oscar for scientific and technological achievement in 2003. The digital art behind the art of cinematography continues to evolve: 3D printing, also called additive manufacturing, is now another option for producers and cinematographers alike. The former like it because they can reduce production costs in some cases, and the latter are thrilled because real props and real costumes allow greater latitude in the moment rather than having to be locked into what was decided months ago on a storyboard and fed into a computer. Traditionally, models would be made by hand and then go through iterations before final approval for filming. That’s expensive. With large objects it is even more expensive. 3DP objects, be they props, costumes or parts of a set, can be created in miniature, tweaked and then approved for large-scale production.

They’re also uncannily real. When James Bond’s classic 1964 Aston Martin DB5 was blown up and simultaneously shot to pieces at the end of Skyfall, more than a few of us gearheads winced and many cried out in pain. Later, to our collective relief, we discovered the prop was one of three 1:36 scale models made from 18 3DP parts. Good job, too, since one of the 1,021 real DB5s made between 1963 and 1965 are worth a lot more; the original Goldfinger DB5 is worth US$2.6 million. Incidentally, a “gold-plated” version recently sold for US$99,041 at a Christie’s auction house as a charity fundraiser. Guardians of the Galaxy, Iron Man 2 and 3, even Zero Dark Thirty, in which the night vision goggles were actually 3DP models, and The Hobbit are among the big titles with 3DP credits. On a more theoretical and creative level, as David Didur, design director and co-founder at Think2thing, a Toronto-based 3D modeling studio, notes, there are some really creative advantages to having real objects in hand to shoot. “I was listening to Jason Lopes of Legacy Effects who worked on Iron Man and he talked about the tyranny of CGI; how it has to all be planned out,” said Didur, who was involved earlier this year in scanning and creating a 3D sculpture of the bell from the Franklin expedition’s Erebus that was recently recovered. As he tells it, his collaborator had an epiphany around 3D during the prep work. “We had the bell out of the seawater and we had it for five hours to scan, and we were working with Lions Gate, which was making a documentary of the recovery,” he said. “We didn’t want to say we were making a 3D model. It was so much more. We saw it as a portrait. We used photogrammetry, which maps the surface in 3D, and then photographed it at 15 frames a second. The software then assembled the data to make the objects. As my partner Ed Burtynsky pointed out, this is really photography 3.0. If film and chemical was 1.0 and digital was 2.0. This is the next form.” As he notes, 3DP has gained traction because it’s a perfect convergence of materials, technology and software. Whereas Maya, the state of the art 3D software in 1998, required massive processing power at the time and huge storage, today, power and memory are cheap, and basic 3D design software comes free. Metals can be sintered with lasers, objects can be extracted from liquid pools, plastics, gypsum, even chocolate can be 3D printed. The unreal has become reality.

Ian Harvey is a Toronto-based journalist who writes for a variety of publications and covers the technology sector. He welco mes feedback and eagerly solicits ideas at ian@pitbullmedia.ca

COME SEE US AT PROFUSION 2015.

The Industry’s only trade show geared to pros.

Credit: Courtesy of Rapid Prototyping (IN TOTAL, MORE THAN 100 LEADING MANUFACTURERS)

Presented by

The Visual Technology People

Othello Ubalde

Goes Into The Interior

James is tired of his life – his dead-end job in Toronto, his no-account boss, his go-nowhere girlfriend. A confrontation with the boss and a distressing medical diagnosis leads to a decision to leave The Big Smoke and find some peace. He flees to the remote British Columbia interior, ostensibly running from his life, but in reality, running from himself. Once in the woods, he discovers that he is not alone. Someone is following him. And he begins his slide down the rabbit hole. The Interior, director Trevor Juras’ first feature-length film, is the story of one man’s descent into madness. Shot in Toronto and in the beautiful, otherworldly forest of Salt

By CHARLOTTE EMPEY, SPECIAL TO

CANADIAN CINEMATOGRAPHER

Spring Island off the coast of British Columbia, the film starts out as a dark comedy and slowly morphs into a psychological thriller. James’ breakdown drives the narrative, and his unravelling is spookily captured by the film’s look and feel. “Trevor was clear about what he wanted,” director of photography Othello Ubalde explains. “And that was to invite the audience into James’ reality, to experience his unravelling through lighting and composition.” Exploring James in the first act, Ubalde was charged with shooting from the audience’s point of view, to create a level of intimacy between the audience and the actor. “I shot primarily

handheld medium to medium-wide,” Ubalde says, “to create the sense that the viewer was in the room watching James begin to fall apart. I used dynamic handheld shots when the actors moved. Where possible, we shot long takes to engage the audience in the tension James was feeling in that particular moment. I used mostly a 35 mm or 50 mm to create the scene from the perspective of the human eye. I shot with a RED cam for a clean digital look. The colour leans closer to the warmer side, which underscored the dark comedy tone. And I used a Schneider Xenon FF-Prime lens – it offers less contrast – which captured the dark comedy vibe Trevor was after. “I used natural light wherever possible to support the voyeuristic feel. If I had to use additional lighting such as the Hexolux D7 or the Fenix flashlight, I wanted the outcome to feel as if there is no lighting at all. “From a compositional standpoint, we were well aware of what was in the frame. We were after certain textures that would help set the mood. For example, dense fog in the background when James was wandering through the woods.” Films conventionally use dialogue and action to explore the characters and move the plot forward. Once James arrives in the woods, The Interior becomes a one-man play – the narrative depends on the audience getting inside James’ head and eavesdropping on his internal conversation. “We tried to achieve a real-life feel and only augment the lighting where it was critical for effect,” Ubalde says. “The goal was to suspend the viewers’ belief, to fully engage them in the story. And that meant it needed to look real, not manufactured or manipulated.” The film’s first act is essentially a dark comedy that takes a tonal turn, and the aesthetic had to follow suit, moving from softer, less contrast to colder, higher contrast. “I needed portable, lightweight support gear I could break down easily,” Ubalde explains. “And with no electricity or a generator for the night scenes, I needed a light fixture and high-output flashlight.”

Director Trevor Juras wanted to show how vast the forest is to underscore James’ isolation.

The solution: a Hexolux D7 Fresnel LED light that could run off a V-Mount battery, Fenix flashlight (they throw a 700-meter beam) and a Panasonic GH4. “This camera was perfect for what I needed,” says Ubalde. “It’s lightweight and compact, easy to transport, has excellent battery life, is very robust and is weather sealed. And most importantly, it has excellent dynamic range, which captured high-contrast images very well.” The camera’s only shortcoming: out of the box, the GH4 low-light settings were not good enough for the quality images Ubalde wanted. “I discovered a Panasonic GH4 how-to video on Vimeo, used this to tweak the settings, and did tons of testing in pre-pro,” Ubalde says. “It was great.” For camera stabilization, Ubalde used the DJI Ronin 3-Axis Brushless Gimbal for the long tracking shots through the forest. For the handheld rig, he used one made from Redrock Micro. As James’ paranoia grows, the tension mounts. When James scrambles out of his tent to see who is stalking him, Ubalde started with a medium shot inside the tent, then moved outside for an over-the-shoulder, then moved to a wide shot. “The scene was intended to create suspense without payoff,” Ubalde says. “So I wanted to film in one long take. We could have had cuts, but we wanted to keep the tension high. I stripped the handheld rig down to two handles and no shoulder pad, which allowed me to start shooting inside the tent, move quickly to an over-the-shoulder shot and then move to a wide as James left the tent and walked into the woods, the camera following the movement of James’ flashlight’s centre beam.” Juras wanted to show how vast the forest is to underscore James’ isolation – internally and in reality. In a number of scenes the forest becomes the co-star, so Ubalde often shot in a poetic manner, treating the ‘set’ as if it were a character. “In the scene where James walks through the forest, I used a wide-angle lens on the Ronin gimbal for a stable shot and a Tokina lens – it has a short hyper-focal distance – to keep James in focus as he walks. We waited for the right weather conditions to shoot this scene; we wanted dense fog to add texture. It was difficult to track James while maintaining the framing continuity. I counted the paces and made mental notes of potential obstacles. For example, if the ground was uneven at pace seven, I knew I needed to step a little higher.” Recognizing the film starts as dark comedy and becomes a psychological thriller, Juras included a scene where James breaks into a cabin, takes a shower, and then writes a thank you note to the cabin owners while he enjoys a glass of wine. “This scene had comedic overtones, so lighting was much less dramatic,” Ubalde says. “The kitchen had big windows and a skylight so lots of natural light filled the room. This scene was also a nod to Werner Herzog, and one of his courses Trevor attended, where Werner suggested that every filmmaker should learn the art of lock picking.” (roguefilmschool.com) Camera movement was motivated by each scene’s action – a locked-off shot to provide the audience’s point-of-view; a handheld shot to give the scene more energy and make the action feel more frantic. “There’s a dream sequence where James is being chased through the forest,” Ubalde says. “Trevor wanted a more stylized shot to show James’ building fear as he runs. I placed a Hexolux D7 camera on the left and shot using a handheld rig to make it feel as if you’re right there with him, experiencing the tension. I shot at 96 frames per second and slowed it down to 24 frames per second in postproduction to build suspense.

What I Learned from the CSC Lighting Workshop

by Othello Ubalde, associate csc

Ihad the privilege of taking the CSC Professional Lighting Workshop with Carlos Esteves csc in April 2014. One of the first things he said to us when opening the course was, “Develop your vision.” I think about that often while working on projects. I suppose I thought that he would get straight into the nitty-gritty of cameras and lighting etc, but he first made sure to spend time stressing the importance of having a vision or an idea of how you could make your mark as a unique individual in the cinematography profession. When discussing upcoming projects with people that are considering using my services, they like to ask questions like, “What’s your style?” I don’t have, nor do I believe in having a specific style, because I believe it’s my responsibility as a cinematographer to be versatile enough to help my client achieve their vision. I certainly have sensibilities and preferences (naturalistic lighting, motivated camera movement etc), but on production day I take pride in being flexible. I believe that cinematography is intended to serve the director’s vision. At the end of 2014 and into 2015, I had the pleasure of working with director Trevor Juras on his feature length film called The Interior. The film recently premiered at the Fantasia International Film Festival in Montreal, and it was just announced that it will be screening at the Saskatoon Fantastic Film Fest in October, and hopefully some more festivals by the end of the year. Working on The Interior was an opportunity for me to apply my knowledge and understanding gained from the lighting workshop as well as other experiences I’ve had. What made this a challenging shoot was that most of the film takes place in the forested area of Salt Spring Island in British Columbia. The first challenge was that I was unable to view the locations ahead of time. We arrived from Toronto the day before we started shooting.

“I lit only one side of his face and let the other side fall into complete darkness. I used a couple of Fenix flashlights, handheld from behind, giving James some edge light to pull him out of the dark background and make him the focus of the shot.” Light was integral to capturing James’ break with reality, and when you’re committed to shooting with natural light (and a limited budget) you don’t have the luxury of do-overs. “Trevor wanted a scene that showed how thin James’ soul had become,” Ubalde explains. “I waited till dusk. There was just enough light to read James’ face. He tilts down his head, his face goes into darkness, and you feel the black chasm of his loneliness.” Ubalde created poetic images to illustrate the juxtaposition of the forest’s beauty and James’ fractured state of mind, and this is, perhaps, most evident in the film’s closing sequence. Ice water. Lush vegetation. Perfectly vertical trees. – metaphorical prison bars “We shot mid-afternoon,” Ubalde explains, “primarily with a 35 mm lens with an Induro Hi-Hat tripod. Most of the shots were framed as a medium shot. You could see some details around the subject. The final shot was a wide shot of the trees to give you the sense that you have been overcome and trapped by nature much like James was inside his own mind.” Shooting The Interior was a collaborative effort, Ubalde says. And that’s why he loves working with Trevor Juras. “My job is to bring the marriage of technical expertise and creative vision to the project – Trevor respects that – and the experience of working as a team to realize the film was really fabulous.”

UBALDE’S…

GH4 SETTINGS

Cive V Contrast -5 Sharpness -5 Noise reduction -5 Saturation -5 Hue -2 Highlight +2 Shadow -1 I.Dynamix: LOW I.Resolution: OFF Master Pedestal Level +10 Luminance 0-255 Keep ISO under 1600

ICONS

ALEX WEBB Because he shoots in layers SAUL LEITER For his painterly approach ROGER DEAKINS asc, bsc For his naturalistic lighting and motivated camera movement

MENTOR

CARLOS ESTEVES csc “The most important thing to do is develop your vision.”

Director of photography Othello Ubalde

Trevor and I would scout the locations the day before we shot, so every day was a brand new logistical challenge. Shooting in a forest requires giving up control of the elements. We were forced to adapt to the conditions, which were ever changing. Stylistically, we wanted to give The Interior a realistic feel. In order to do so, the lighting needed to appear as natural as possible so as to suspend the viewer’s disbelief. My saving grace in these situations, and a little trick that I picked up at the lighting workshop, was my Sun Seeker app, which gives me a 3-D view of the path of the sun at any given hour of the day. I have multiple examples of when this really helped us decide when to shoot. One example is when we picked a location where we wanted to shoot a scene that called for dramatic shadows. Sun Seeker told me where and when the sun would start to drop behind the tree line, so we could perfectly time the filming of this scene. It ended up looking perfect. Pre-production is one of the critical elements in my approach to filmmaking. I believe that doing your due diligence and putting in the necessary time upfront frees your mind to be more creative and quick thinking on production day. Consistent with the teachings in the advanced lighting workshop, I’m a stickler for being intimately familiar with my equipment. There is nothing worse than being out there and having to worry about your lack of familiarity with gear that you might need to use that day. It’s unprofessional. Being confident and well prepared during a shoot has allowed me that extra brain space necessary to think on my feet, make creative decisions and deal with unpredictable situations as they arise. Filming can be, and is with me, a very intuitive process, and I like to be uber-prepared from a technical standpoint because you’ll never know when that creative moment will happen.

Credit: Caitlin Cronenberg

What films or other works of art have made the biggest impression on you?

As a child in the ‘70s, I got my hands on books, and my first encounter with the world of storytelling was with Tintin and Astérix, the Belgian graphic novels. The ninth art is still an inspiration for me today and I still love to study its visuals for editing and composition.

How did you get started in the business?

When I was about to finish the film program at Concordia University, I met three guys at school with whom I opened a small production company. We knew that there was no other way to get a job we wanted unless we created it. We essentially worked for three months straight during the summer, producing, directing and shooting music videos. In the fall, we became so broke that we closed the company and parted with $4,000 each in debt. But we had a hell of a nice demo to show around in the industry. I then started to direct and shoot commercials, and my first feature as a DP came my way when I was 26.

Who have been your mentors or teachers?

There was a cinematography class at Concordia, and the teacher was an old cinematographer called Georges Dufaux who had shot tons of documentaries at the NFB and many features. This was his first gig as a teacher and he couldn’t talk about cinematography for the life of him, so people just left the class, but three of us remained. It became a very intimate class and that’s when Georges decided to show us rather than tell us about the art of making pictures. We tested stocks and cameras and tried lighting setups. He lent me his director’s viewfinder and would come to my student film sets and discreetly propose ideas for me to work with. On a student film I was shooting, I vividly remember when he climbed on an apple box and rigged some lights on the ceiling with the student gaffer to make time. That old man was the most striking inspiration for me because it is his artistry that taught me about camera and lighting. Georges taught me that I can talk about it all I want, but in the end, it’s on a set that things happen. His passion was tremendously contagious and I learned to use my instincts rather than follow a recipe. I owe him much.

What cinematographers inspire you?

I mostly like the older generation who made films I grew up on, that I still study today – Storaro, Willis, Savides, Deakins, Toll – they always made (or still make) films that matter, that remain encrypted in the cinematic universe. I respect them for their work but also for their choices as artists. They know that getting along with a director and making a good film rather than a film to show off is the key. I also love Bobbitt, Prieto, Libatique, Lubezki, Khondji and Mantle because they dare to try new things and put themselves in danger. The

truth is I hate the bland-uncinematic-digital-beige cinematography that some cinematographers do today.

Name some of your professional highlights.

I have to mention that winning at Camerimage with War Witch was not just a surprise but also an irreversible career driver. The films I did in those years have all been memorable to me because I’ve been working with crazy inspiring people that drive my own passion for film. Of course there’s also Enemy because working with Denis Villeneuve again after Next Floor made me more confident about my approach with the kind of films I really want to make – they are actually the ones I love to watch.

What is one of your most memorable moments on set?

Twenty years ago, as a student, I visited a friend working on an American film shooting in Montreal. Between two takes, I sat quietly amongst the equipment, keeping to myself until I crossed Bruce Willis’s eye-line during his acting. On cut, I quickly sneaked off the set hearing Willis fume about how distracted he got during the take and now everything was shit because some kid was in his damn eye-line.

What do you like best about what you do?

Travelling the world and visiting so many places that are hidden to the common traveler. Also, meeting so many inspiring and talented people in a single year to me is mindboggling.

What do you like least about what you do?

I hate justifying to a stubborn producer or a production manager how the hell my job is important and why I need to use some particular gear that the film needs. Those never-ending, redundant, souk-like negotiations make me crazy.

What do you think has been the greatest invention (related to your craft)?

I’m fascinated by the formats we use in cinema. I think that since the anamorphic format appeared, there’s nothing to measure against it; it’s in a category on its own and it seems that it can never be challenged. Cinema has an obsessive love affair with the anamorphic format, as I do.

How can others follow your work?

nicolasbolduc.com and imdb.com/name/nm0092839