23 minute read

On Set

Credit: Tomo Nogi Going for a real flight in a vintage North American Harvard plane using an ARRI ALEXA Mini, associate member Sarah Thomas Moffat DP'ed and operated the narrative film Boundless.

Credit: Rory Sommerville-Bathmaker Director Tony Kaplan and DP Christina Ienna (associate member) frame up Pixar animator Steven Hunter with a Sony VENICE rigged above on the set of the documentary series Inside Pixar: Steven Hunter.

Cinematographer and associate member Dana Barnaby on the set of Hearts of Winter (aka A Tidy Romance).

Credit: Sean Guzen

DP Quan Luong (student member), Steadicam operator Pedro Simone, 1st AC Ryan Offenloch (student member) and 2nd AC Alex DC on the set of the short film In Love We Survive (dir. Omar Benson). 10 • Canadian Cinematographer - April 2020

Credit: Nathan Garfinkel Associate Member Dennis Grishnin on the set of a music video for “I Drive Me Mad” by Ren.

Featuring: E117 Steel Blue, E089 Moss Green & E164 Flame Red

Capture your shot with authentic Rosco gel colors created by MIX LED technology.

Every gel color in the MIX library has been scientifically validated by Rosco’s color experts. Patent-pending MIX technology blends six LEDs to produce a fuller color spectrum than RGBW and RGBA fixtures. With the myMIX app, complete color control is in the palm of your hand.

Genre Bender Bobby Shore csc Builds

CASTLE in the GROUND

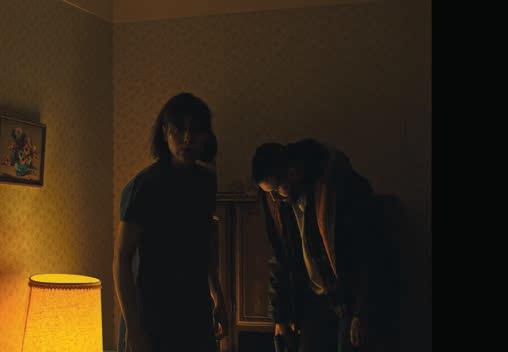

In actor-turned-director Joey Klein’s feature film Castle in the Ground, a young man living in Sudbury is the primary caretaker for his terminally ill mother, administering daily doses of OxyContin to ease her pain. When his mother dies, the teen, Henry, befriends his charming but troubled next-door neighbour, Ana, who is struggling to kick her own drug habit. Henry eventually becomes drawn into Ana’s sordid world and caught in the crossfires of the opioid crisis. Hereditary’s Alex Wolff leads the cast as Henry, with Neve Campbell playing his mother, Rebecca, while Imogen Poots (Frank & Lola, 28 Weeks Later) plays Ana.

Bobby Shore csc

By Fanen Chiahemen

Bobby Shore csc, who photographed Castle in the Ground, notes that Klein took a somewhat unconventional approach to handling the heavy subject matter. “I think what stood out the most was how it starts off as a character-driven tone piece and then almost imperceptibly shifts into a plot-driven genre piece,” Shore says. “I remember some of the initial conversations really being centred around how we could use aesthetic tropes of genre pieces to inform how we would film some of the more character-driven tonal aspects and vice versa.” French director Robert Bresson’s signature style was an inspiration for the film’s visual language, the DP reveals. “We watched a bunch of “With Joey old Bresson movies just because he was everything is just so restrained with the way he used the camera,” Shore says. “We were really inabout talking terested in the idea that what works best in psychological thrillers and horrors is about the tone never really knowing what is waiting for and emotional you just outside the frame. And the way Bresson uses a very locked-off camera and character of a specific sound design, it cues the viewer’s scene. It becomes imagination to wonder what’s going on outside of what you’re looking at. a very intuitive “Joey wanted to shoot and frame in 4:3 because he loved the idea of these black and explorative bars on either side of the screen, almost process between like the viewer wants to push the bars to the side to see what’s waiting around the the two of us.” corner,” Shore continues. “And so that became, at least for me, a very important jumping-off point as to how we’d use the

camera and how we would frame things. A lot of the time, we would try to frame the characters with a lot of foreground elements stacked to help amplify this sense of claustrophobia and help give the sense that sometimes maybe the characters are being watched, or if we’re really present with them that we’re holding on close-ups for a very long time and using sound design to try to intuit what might be happening around them.” Having worked on two features and four short films together, Shore and Klein had developed an efficient shorthand that came in handy especially when prepping the film. “I can definitely say that it’s by far one of the most collaborative processes working with Joey from every standpoint,” Shore observes. “We had two passes of the shot list done a month before we even started official preproduction, and so with Joey everything is just about

talking about the tone and emotional character of a scene. It becomes a very intuitive and explorative process between the two of us.” Shooting on location in Sudbury allowed the production to take advantage of Northern tax credits, and the city was also an ideal setting to depict the impact that the opioid epidemic has had on small towns, although the location came with challenges. “From a logistical standpoint, it was one of the hardest shows I’ve ever worked on, and that had a lot to do with the hardships of shooting a movie in the dead of winter in Sudbury and the fact that there were five blizzards and six feet of snow on the side of the road, and just moving gear around outside became a massive ordeal,” Shore reveals. He, Klein and production designer Zosia Mackenzie scouted

Clockwise: ImogenPoots, Alex Wolff and Tom Cullen in Castle in the Ground. Imogen Poots and Tom Cullen. Imogen Poots as Ana. Alex Wolff. locations in Sudbury a couple of months before preproduction and found an apartment that would serve as the main location where most of the film takes place. “To Zosia’s credit, being as collaborative as she is, she was able to take the bones of something that would work very well from a camera and lighting standpoint and transform it into something that worked from a character standpoint for both Henry’s and Ana’s apartment,” Shore notes. “And knowing how much time we were going to be spending in these places, it became really important to utilize the space in the ways that would help propel the elements of the horror genre that we wanted to use in terms of having the camera float in and out of rooms and looking around one corner to another. Zosia was pretty instrumental in helping to cultivate and create a look and feeling because the apartments were basically just empty shells, and she totally designed a nice aged, well-worn feeling for both of them.” For lenses, Shore went to Panavision. “As always, I just tested a bunch of old shitty standard speed lenses and handpicked the ones that felt like they were the best feeling for the film,” he says. “And usually, in the past, I’ve used more Super Speeds or Ultra Speeds, but given the texture and feeling that we really wanted for the image, I wanted to go even older and use more of the standard speeds. We shot about 80 per cent of the movie on an old 40 SP, and the remaining 20 per cent was shot on a Close Focus 35 that we used for all of the macro work. And then obviously, if we needed to throw in a 29 mm or something, we would do that every once in a while, but the majority of the movie was a 35 or 40 mm, and it just felt like the right focal length. It let us see enough of the space but still kept things feeling a little bit claustrophobic while still getting a sense of proximity between the camera and the actors.” One of the biggest influences for lighting from a texture and tonal standpoint was the photography of Nan Goldin, he says. “If you look at what she was doing with people that were in her close friend circle in the ‘70s and ‘80s, there was a sense of intimacy and a very raw sense of loneliness,” Shore states. “So if it was a day scene, all the light was motivated from the windows,

and if it was a night scene, it was a streetlight or a lamp that was turned on, and that became the M.O. in terms of really wanting things to feel not really lit that much. And for day scenes, a lot of times we wouldn’t light at all; we would just use whatever natural light was coming in, and then if we lost the light, we would augment it and recreate our own daylight if we had to do night for day. “If you came on the set and we were doing a night scene, the setup probably looked worse than a student film,” he continues. “Because we would just have a 1K outside a window. We wanted it to feel motivated from sodium vapour streetlights, so we’d either use actual sodium vapour fixtures or we’d use MTY on the light that replicates the sodium vapour look pretty well just to light the sheers. It felt so rinky-dink and small, but it worked really well because of the sheers that Zosia put up that gave so much texture to the light or the wallpaper that was behind the character and would reflect and pick up the light so well that you didn’t need to augment or do anything else. “When we were staging night scenes where lamps would be on, we’d just keep everything motivated from a lamp source, so if there was a lamp in the corner, we would take a lite mat and then throw a bunch of unbleached muslin on it and put it right next to the lamp, and that would be our light. So if the characters moved away from the lamps, they would just go into shadow and if they moved towards it, they would move into their light,” he says.

Jason Vieira with Shore and Wolff on set.

“One of the elements that I think can get under utilized from the standpoint of visual storytelling is lighting contrast,” he observes. “And one thing that me and Joey spoke about doing very intentionally was as Henry gets deeper and deeper into this world, we wanted to use harder and harder light on him. So even

in scenes that didn’t make sense to have the lights turned off inside the apartment, we would just turn them off and have the inside lit by what would look like a streetlight coming in from outside a window, just as a way to build up the contrast and get much darker, really rich shadows and not being able to see everything so clearly as a way to visually represent his descent into this darker world. From a camera standpoint, it became a lot about using the camera in very locked-off frames and letting Henry move in and out of the frame or stacking a lot of foreground elements in front of him so that he starts to feel kind of trapped.” The camera was locked off 90 per cent of the time during the shoot or on a dolly, with a couple of big Steadicam shots executed by Jason Vieira and associate member Andreas Evdemon, Shore says. Jim Fleming completed colour timing on the film, using a variation of a LUT that Shore used on another project earlier that year, and which he tailored to suit the visual aesthetic the filmmakers were going for. “I think it really captured the tone and texture of the old Nan Goldin photos from the ‘70s and ‘80s,” Shore says. “She used a chromogenic print process called C-41, and when you see the light on a character’s face, it has a kind of subtle filmic roll-off to the highlights and information in the shadows, but you still really feel the contrast of the source. Of course, having worked with Jim on multiple features and TV series and really trusting his taste, he was able to really finesse it and hone in on all the aspects of the lighting that the LUT really brought to the image.” Klein being an actor as well as a director was an advantage to the production, Shore maintains. “When we did his first feature The Other Half together, I felt like I was learning more from him than I had learned from almost any other director I’d worked with before, and that had everything to do with the way he spoke with actors and the way he approached everything from the perspective of an actor,” the DP says. “So I felt like I was learning something new because I was listening to the words he would use to describe motivation or an intention of a feeling, and hearing him use those words infused in me a deep understanding of what a scene was actually about, so the conversation became elevated and more about subtext and the more ethereal, emotional unspeakable stuff.”

Like A Boss Bloodshot Midsommar Dolemite Is My Name Hustlers Just Mercy Wu-Tang: An American Saga The Witcher The Dry Veronica Mars American Horror Story Your favorite stories. Told with .

www.panavision.com

Dickinson Evil Maniac Tales from the Loop The Terror Homecoming The Highwaymen The Hate U Give The Rook Mary Queen of Scots The First Can You Ever Forgive Me? All the Bright Places Velvet Buzzsaw True Detective The Good Fight

Paul Sarossy csc, asc, bsc

Looking Back at

By Fanen Chiahemen

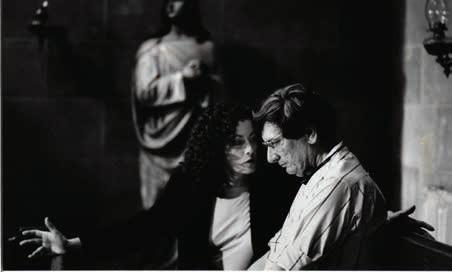

In 1996, Paul Sarossy csc, asc, bsc served as director of photography on the feature film Mariette in Ecstasy, an adaptation of the Ron Hansen novel that depicts a 17-yearold girl’s religious fervour when she enters an upstate New York convent as a postulant. The film was directed by cinematographer John Bailey asc, and it was on the set that Sarossy met his wife-to-be, actress Geraldine O’Rawe (Circle of Friends, Adoration), who played the lead, Mariette. Due in part to the bankruptcy of production company Savoy Pictures, the film was never released, and few had seen it until it was screened late last year as part of a retrospective of Bailey’s career. Despite the years that have passed, Sarossy clearly remembers his first meeting with Bailey. “We immediately connected when talking about this French film by Alain Cavalier called Thérèse, which was subject-wise very similar to this film and very beautifully photographed. I could see his eyes light up when the conversation went in that direction, and I kind of think that was the moment when I got the job,” Sarossy says. For Bailey, who served as president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences from 2017 to 2019, his first meeting with Sarossy was just as memorable. “As soon as I met with him, I was just captivated by

his enthusiasm – and I mean this in the most positive way – his kind of boyish energy and enthusiasm,” Bailey recalls. “I felt on a certain level he would be a counterpoint and a balance against my own inherent sense of pain and guilt-ridden Catholic obsessions because he seemed to be very life-affirming and very positive. I thought Paul would help keep me from falling into a penitential pit, and he did. So I asked him to do the film as much for his temperament and his personality as for his work. And of course once we started to make the film and I actually watched how he would light, I thought, ‘Boy, this is great.’ The lighting is Paul’s completely; I just left him alone.” Baileys’ hands-off approach to the cinematography was one of the things Sarossy most appreciated about the director. “He was a wonderful person to work with, a great collaborator, because he absolutely didn’t interfere with the photography and the lighting of the film, which is of course the obvious fear when you go into a working relationship with a well-known cinematographer. Will he be able to resist getting his hands dirty,” Sarossy says. “And he was wonderful that way. But he was also a very verbal person, unlike myself, so he very much was able to talk about and describe paintings and works of literature, other films and visual references that he was interested in.” Bailey, who was raised Catholic and had initially planned to enter a Jesuit novitiate to become a priest, says he was always interested in filmmakers that dealt with metaphysical themes and was influenced by directors like Michelangelo Antonioni, Ingmar Bergman and Robert Bresson. “The common visual style I saw in all their films was a tremendous sense of formality; a

Paul Sarossy csc, asc, bsc

Geraldine O’Rawe

Top: Actress Geraldine O’Rawe. Bottom: Helen Hughs, Janet Wright, Soo Garay, Nancy Beaty, Meg Hogarth and Deborah Lambie. Left page: Actress Geraldine O’Rawe, DP Paul Sarossy csc, asc, bsc and actress Eva Marie Saint.

“I thought Paul would help Both photos O’Rawe as Mariette.

keep me from falling into a

penitential pit, and he did. So I asked him to do the film as much for his temperament and his personality as for his work,” John Bailey asc certain kind of pageantry, or a controlled processional ritualistic imagery, one shot succeeding the next in a kind of classic way. And I thought the formalities and rituals of the religious life were very interesting to explore in the film,” Bailey says. “But I didn’t want it to look too devoid of rich imagery. You think of Bergman and Antonioni, especially the black-and-white work, it’s very spare and elemental in terms of the use of visual elements, so I decided I really wanted to shoot it in colour rather than black-and-white, and I wanted it to be wide screen anamorphic because I saw a lot of the movement and action in the film in this kind of horizontal processional way, the ritual and the movement of the nuns within the convent.” The anamorphic format also “lends itself to the frame being very solid and the filmmaking not being too cutty or edited because of the wide frame and the fact that you had an ensemble cast where at any given moment there are may be five or six people in the frame,” Sarossy observes. “Because it’s a convent, in a sense, there is a kind of proscenium that everyone is performing in.” Casting the film with actors primarily from the theatre also served the film’s style, according to O’Rawe. “John wanted this sparseness to be present in the movie to counteract the intensity of Mariette’s journey,” she says. “It was a visual balance to the emotions Mariette was feeling while in ecstasy. This style of filming mimicked the simplicity and ritualistic nature of the life of the nuns. There is a monotonous tone to life in a convent, every small moment, every little detail, holds more meaning than it would in a fast-paced world.” The sparseness is mirrored in the lighting, with candles lighting a lot of the film. “Pretty much in the convent it was all candlelight,” Sarossy recalls. “I guess now looking at this film in retrospect, it really makes you realize what a different approach you would take today. We are now at a moment in digital cinematography where you can actually light with a candle, but in those days it was utterly impossible, you had to make various efforts to create that illusion and mimic candlelight artificially.” Although the tools of the trade have become more efficient, Sarossy suggests shooting the old-fashioned way was more creatively satisfying. “I feel lucky to have gone through the period of time where film was less sensitive. You had different tools and had to do things another way,” he remarks. “Today, you’re almost throwing away as much lighting as you’re embracing. In the olden days, you started with nothing and added one light after the next; it was an additive process.” Both Sarossy and O’Rawe fondly remember the Toronto shoot and the dedication of the cast and crew. “I remember everyone, particularly myself, John and Paul, being totally tunnel-visioned as to what we wanted to do,” O’Rawe says. So she barely paid attention when actress Eva Marie Saint (who played Mother Saint-Raphael) came up to her and, pointing to Sarossy, said, “See that guy there? You should marry him.” O’Rawe says she laughed it off, but the seed was planted for a courtship with Sarossy. “It was when I sort of started to pay attention,” she recalls. “After that, we chatted a bit and got to know each other, and a whole other layer was added to the making of this beautiful piece.” Then after the production wrapped, Mariette in Ecstasy “just

RONIN 2

Producer Alba Francesca and John Bailey asc.

sort of disappeared,” she remembers. Bailey declines to elaborate on the “ugly politics” that led to the disappearance of the film but cites “creative differences of opinion” with co-producer Frank Price “that increased when Savoy became very unstable financially and went bankrupt.” Bailey eventually withdrew from the project late in postproduction. “With the bankruptcy of Savoy, no distributor would pick the picture up, so it just kind of languished for several decades and it was too painful for me to look at it again,” he says. Then in August of 2019, when the Camerimage Film Festival announced it would be honouring Bailey with a Lifetime Achievement Award at the 27th edition of the festival in Toruń, Poland, Bailey decided to add what he calls his “orphan film” to the retrospective screenings of his works. Mariette in Ecstasy would finally have its world premiere in November 2019, more than two decades after it was shot. After so many years, Bailey says he was surprised to find himself getting “caught up in the movie” during the Camerimage screening. “It was the first time I was seeing it with a room full of people who knew nothing about the movie, projected on a large screen,” he says. “So it was like seeing it for the first time, and I got caught up looking at the emotions and the journey that Mariette takes.” He was particularly struck by O’Rawe’s performance. “Truly transcendent in my mind is the absolute conviction that Geraldine brings to the role of Mariette,” he says. “It’s a kind ofno-holds-barred performance; it’s very courageous, very naked. I’m just swept away by her performance.” O’Rawe indicates that Bailey’s directing style allowed her to give such an honest portrayal of Mariette. “I trusted John and Paul to have my back, and simply tried to deliver a sincere performance of a young girl who was deeply and passionately in love with God,” she says. “I felt very much embraced and I felt safe; I was left to deliver. He trusted me to have done the research and to put on screen what he wanted to see.” The actress says she was “overwhelmed and surprised” when she saw the film at Camerimage. “I hadn’t messed up, which is what I thought I had done so long ago. I had not for 20 years seen the finished movie, and watching it, I felt a part of me – the part I had given to this role – come back. During the Q & A after the screening, I could see a shift in all of us, something had changed in John, Paul and I. The piece that had remained incomplete and unresolved had found closure.” As for Sarossy, seeing the film after almost 25 years was like “unearthing a time capsule,” he says. “I’m looking at it through the eyes of working with very different methods and tools. I was surprised in a wonderful way, and I was so bowled over by how beautiful Geraldine was in the film.”

MAVIC 2 ENTERPRISE

Set yourself free

Looking for the very best in cinematic camera stabilization or professional or enterprise-level UAVs? DJI has what you need. The versatile Ronin 2 motorized 3-axis gimbal can support payloads up to 30 lb. and can be operated in wide range of modes. And DJI’s modular Mavic 2 Enterprise dual camera quadcopter drone offers a complete enterpriselevel aerial solution. Visit your nearest Vistek for a full demo: as a DJI Drone Solutions Dealer we can provide full lines of DJI Cinematic and Enterprise Drone Solutions.

VISTEK IS AN AUTHORIZED DJI ENTERPRISE SOLUTIONS DEALER

CSC Tabletop Lighting Workshop

February 15-16, 2020, Toronto

Credits: Justin Lovell

in Partnership with ICG 669

Led by: Carlos Esteves csc and George Willis csc, sasc

William F. White, Vancouver, BC February 22-23, 2020

A huge thank you to William F. White, who supplied all the gear (lighting/grip/camera packages), as well as the location.