33 minute read

Spotlight: Christopher Ball csc

CSC MEMBER SPOTLIGHT Christopher Ball csc

What films or other works of art have made the biggest impression on you?

From the first film I saw at age two Disney’s Snow White to diverse films like Lost Highway or The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, there is a huge range of influences that I reference at different times and in different ways. Films that have been thoughtfully designed and constructed to achieve a perfect suspension of disbelief are films that I am most passionate about.

How did you get started in the business?

I started by making films when I was nine years old, after being totally amazed that my parents “owned a movie camera” – a regular 8 Kodak Brownie. I made films through high school on Super 8 film, went to Ryerson for the Film & Photography program and started PA’ing in commercials and then drama. As a filmmaker, I was shooting short films, music videos and documentaries on the side as I was working my way up in the business, which ultimately led to a lateral mid-career move. I had always thought I wanted to direct, so I followed that career path by making “indie” films and working my way up as an assistant director. However, it became clear to me while working on projects with other indie filmmakers that my real love was with the camera, and I found a great deal more satisfaction as a DP than I did as a director, so eventually I followed through with that change of plan.

Who have been your mentors or teachers?

My first mentors would be my parents, both of whom were involved in creative pursuits and exposed me to a wide variety of theatre, film, music, literature and art from a very young age. I have to also thank my grade 10 teacher who told me that film was an actual career that you could get paid for working in, when I was unsure what to choose for postsecondary education. Two cinematographers who had an influence in how I think about shooting are Rene Ohashi csc, ASC and more recently Eric Cayla csc. They both “upped the bar” and encouraged me to go for things I might otherwise hold back on.

What cinematographers inspire you?

If I had to choose, I would lean towards Roger Deakins asc, who has a style and an edge (and a risk) to his shooting that I admire. But I also admire films shot by Peter Deming asc, Ellen Kuras, Sven Nykvist, Ron Fricke, and even the experimental innovations of Norman McLaren at the NFB.

Name some of your professional highlights.

I did a series of films in the Eastern Arctic which were explorations of Inuit culture and history. Working on these films, with Inuit crew and elders, in extreme weather conditions far from any amenities, was one of my most satisfying and challenging work experiences (try changing a lens at minus 59 in ice fog next to the floe edge. It takes about 20 minutes). These films captured an important part of our history, and there is great satisfaction in being part of that.

memorable moments on set?

Recently, scuba diving with a school of 900-pound tuna has to be up there, but that moment is indicative of one of dozens of “I-can’t-believe-I am-doingthis-right-now” moments that are typical of this career: Shooting on the high parapet of a 900-year-old castle in Luxembourg at sunrise, chasing hang gliders with an ultra-light plane, hanging off the side of a schooner in 16-foot waves.

What do you like best about what you do?

The constant exposure to new experiences and the never-ending learning. Also the thrill of seeing a finished project on the screen, especially when you see it really work the way you had intended.

What do you like least about what you do?

There is a certain amount of instability and unpredictability, which is a lovehate relationship. There are times it can be frustrating when you cannot plan your life and you can never commit to anything outside of work until the last minute! I have missed some life opportunities because of that.

What do you think has been the greatest invention (related to your craft)?

The greatest invention ever was motion picture film! But recently, I think it is LED lighting technology. I think that is advancing some of the possibilities of our craft, and to some extent, the approach to shooting, more so than many other technologies. I think LED technology will have a big impact, and with its lower power consumption it should also improve our carbon footprint.

How can others follow your work?

I have a website, cbifilms.com, which has links to many of the projects I have worked on. I am currently on Private Eyes Season 2 as alternating DP with Pierre Jodoin csc.

CSC at 60 The Story Continues

ganization is already looking forward to the next 60 years. The august founders of the CSC might not recognize much of the gear and even some of the technical language of the craft today, but they would see that some things never change: Always tell the story. The CSC itself also has evolved over time. Founded by a group of mostly news shooters and documentary makers, that first meeting of the CSC at a former theatre-turned-film

By Ian Harvey

Bob Bocking csc

Kelly Duncan csc

And… That’s not a wrap.

As the Canadian Society of Cinematographers celebrates its 60 th anniversary this year, the orMike Lente csc

Richard Stringer csc

studio at Woodbine and Danforth Avenues in East Toronto had a simple goal: bring together cinematographers of like mind and vision to share ideas and look to the future. Today there are more than 500 members and 38 sponsors from coast to coast to coast, something attendees at that first meeting could hardly have envisioned. The CSC is more than a trade organization, more than a professional accrediting body – it’s a place to share, learn and grow, not just the art of cinematography, but as creative individuals following their passions. Indeed, the CSC was born to “foster and promote the art of cinematography,” and that has not changed in 60 years, nor will it change in the next 60 years.

From left, Ron Stannett csc, Bob Saad csc, Joan Hutton csc, Richard Leiterman csc and Henri Fiks csc

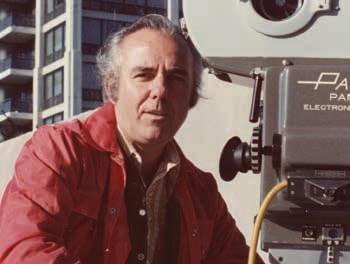

Rene Ohashi csc, asc

John Walker csc

Ken Post csc

Bob Crone csc

Noel Archambault csc

Richard Leiterman csc and Don Shebib

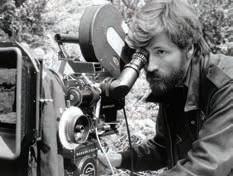

Ken Gregg csc, at the camera, with director Ron Bashford

Burt Dunk csc, asc Roy Tash csc

From that inaugural meeting to the first annual dinner in 1957, the CSC has been about professionals recognizing and celebrating the best works of their peers. It cost a mere $10 a year to join the CSC, then $15 initiation, and the first annual CSC gala and awards dinner event was held at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montreal. It was $6 a ticket. The first CSC magazine was also published that year, to be published six times a year. “Everything the CSC stands for is well worth supporting,” George Morita csc recalled in an October 2007 interview. He joined the founders as an associate member in 1957 at just 20 years old, quickly went on to become a full CSC and won the prestigious Masters’ Award before retiring. “Prior to the CSC, way back in the ‘50s, cameramen were distant. We heard rumours, stories of other cameramen; there wasn’t a sense of camaraderie. The problems affecting one cinematographer affect everyone. It made the art of cinematography more viable.” Flash forward to 1997 and the 40 th Anniversary when Maurice “Sammy” Jackson-Samuels csc noted: “No doubt about it, the CSC gave cameramen a name, it gave us respect in the industry, and it told the industry what we did. It gave cameramen a place in the industry.” Those sentiments are as true today as the day they were first

Joan Hutton csc

Serge Desrosiers csc

Pierre Gill csc

Maurice “Sammy” Jackson-Samuels csc

Manfred Guthe csc

spoken. In keeping with its beginnings, the CSC has always maintained three key elements: communications, camaraderie and cameras, though over time the latter has expanded to include all the technology now common on sets, from lighting to metering to rigs and more. And perhaps more proudly, it’s been done without any government funding or grants for 60 years. Meanwhile, the face of the CSC is also changing. There are more women cinematographers now and room for many more, following the trail blazed by CSCs like Joan Hutton csc, Kim Derko csc and Zoe Dirse csc. Laudably, three of four CSC inductees last summer were women, among them Catherine Lutes csc, who studied film in Vancouver and came to Toronto to work her way up to her designation. “The industry is changing,” Lutes said, noting that more women are entering the field and are eager to get behind the camera on larger budget projects. Advances in technology continue to open many doors, making good gear affordable at any budget level. “It’s more accessible to more people,” Lutes noted. “You keep learning new things with new technology. That’s why the educational component of the CSC is so important to me. You never stop learning.” And as new members are inducted, the CSC will continue

Ron Stannett csc

Kim Derko csc Rob Rouveroy csc

George Willis csc, sasc

Roger Moride csc Robert McLachlan csc, asc

Guy Dufaux csc

to grow through a strategy of inclusiveness set out clearly in 1958 when the bylaws were first drafted: “In all wording bylaws shall treat masculine as feminine,” a way of ensuring women would be welcomed whenever they presented themselves for induction. By 1971 the bylaws were further amended to open up official membership to camera assistants as affiliate members. Every stakeholder in the Canadian film, commercial and documentary sector has played a role because the benefits are shared by all. As CSC Executive Officer Susan Saranchuk says, “The future is never clear, but the CSC is stronger and well positioned for the next 60 years.”

Who doesn’t want to own a piece of the CSC? To commemorate our 60th anniversary, we will include this metal gear label with your CSC 2017 membership receipt! And if you really love it, additional labels are available for purchase on the CSC website.

MEAN DREAMS Steve Cosens csc Chases Teens on the Run

By Fanen Chiahemen

Left: Jonas and Casey fall in love.

In director Nathan Morlando’s second feature, Mean Dreams, Jonas Ford ( Josh Wiggins) is a 15-year-old who spends his days helping his father run the struggling family farm, while his mother battles chronic depression. When Casey Caraway, a girl Jonas’ age, moves to the property next door, the two fall for each other fast. Casey (Sophie Nélisse of Philippe Falardeau’s Monsieur Lazhar, shot by Ronald Plante csc) has lost her mother and is being raised by her aggressive, alcoholic police officer father Wayne (Bill

Paxton). Having witnessed Casey’s abuse at the hands of

Wayne, Jonas takes it upon himself to save her, at first seeking the help of a local police chief (Colm Feore), who brushes him off. Then one night, hiding in the back of Wayne’s pickup truck, Jonas witnesses Casey’s father’s involvement in a drug deal in which a pile of money is exchanged. Jonas impulsively seizes an opportunity to grab the cash, with the intention of using it to rescue Casey, but the teens are forced to flee when

Wayne discovers Jonas’ theft.

The Great Lakes setting – with its gold-and-rust-hued woods for the kids to hide out in, its roadside motels and wide open skies – provides a picturesque autumnal landscape to juxtapose against the suspenseful, fast-moving narrative of Mean

Dreams.

“As soon as I read [the script], I knew right away I wanted a camera that was always chasing, following or moving and that it was dreamy and had the feeling of youth on the run. That was Nathan’s feeling too,” cinematographer Steve Cosens csc says. “We were really synced up that way; we had the same interpretation of the script – it had a certain amount of darkness and was very minimal. We knew it was going to be sparse and stark and moody, and Nathan wanted it to be fable-like. Wherever we could, we tried to push the film into a slightly stylized naturalism.” Cosens introduced Morlando to the paintings of Andrew Wyeth, and Morlando has been quoted as saying he sought to evoke in Mean Dreams the painter’s same dark romanticism and modern gothic realism to express the “darkness that exists in Casey’s and Jonas’ world.” By contrasting the wide, expansive landscapes in the beginning of the film – symbolizing the hope that lies ahead when Jonas and Casey meet – with the more enclosed spaces the teens encounter when they go on the run, Cosens and Morlando mirror the dangers in the physical world encroaching on the youths’ innocence. The changing seasons of Sault Ste. Marie, where the film was shot, also echoes the physical and emotional transition in the teenagers as they come of age and enter into the adult world. “For every scene, we really wanted a specific landscape to help evoke the tone of the scene and we worked hard at finding those special places. It’s not coincidental that in the scene where Jonas and Casey first tell each other they love each other it’s in a wide expanse; it’s kind of the only time that we see that – vulnerability amidst emptiness,” Cosens says. Having shot in Sault Ste. Marie before, Morlando and Cosens were thoroughly familiar with the area and spent much of pre-production trying to find the perfect locations. “We were very particular; we just knew so much of it would be about having the landscape represent an interior space. It required hundreds of miles of driving around Sault Ste. Marie to find the right landscapes for each scene. It was really days and days and days. It would have been so easy for us to just shoot in one area, just go from one forest to another. For sure it would have saved money and time. But we were determined to find the

The teenage runaways count stolen money in a burnt-out bus.

perfect woods, even if it meant stopping and hiking a mile or stopping and taking a quad up in the hills,” he says. “We knew shooting in the fall we would have amazing colours with the leaves changing,” he continues. “We definitely knew we wanted to integrate the browns, grays and autumnal colours in their clothing with the set design and landscape. We chose the buildings and key set pieces that had great aged grays, ochres and rust, and then in postproduction, with the help of Hardave Gruel at Urban Post, we worked to finesse the look by playing with warmth and desaturation as needed.” For Cosens, the RED DRAGON was most suitable for the shoot and worked particularly well at capturing the everpresent sky. “You can use the HDRx function where you can get extra latitude out of the highlights. I used that quite a bit

on exteriors just to really get as much detail out of the sky as I could because the sky was always so dramatic and moody. And because it was the fall, there were often storms in the distance that I wanted to try to define a bit more,” the DP says. The camera also inadvertently creates a striking effect in the film in which the sun appears to be – almost symbolically – burning a hole in a dense canopy of trees sheltering Casey and Jonas. “That was just the fact that the RED sensor couldn’t handle the heat of the sun,” Cosens reveals. “That really is what allowed it to eat through the trees like that. I really just liked the graphic quality of those trees with the sun fighting to get through them.” He outfitted the RED DRAGON with Zeiss Master Primes because he “knew for the night scenes I really needed to be

Images: Courtesy of Elevation Pictures

WHITES,

CAMERA,

• Over25,000 square feetofeco-friendlyprep • 3 feature-sized camera test rooms • • Production-friendly

CAMERA,

ACTION!

prep space • 8 full-service camera testlanes State-of-the-art lens projector room Production-friendly storage solutions

Credit: Courtesy of Elevation Pictures

Mean Dreams director Nathan Morlando. Colm Feore plays the police chief. Jonas (Josh Wiggins) faces off against Casey’s abusive father Wayne (Bill Paxton). able to shoot wide open, and I love the look of Master Primes. You can shoot 1.3 wide open on them and they just have a nice soft look because of absolutely no depth of field and the image starts looking anamorphic,” he adds. He kept his lighting package sparse, employing primarily natural light but with a 6K and 18K on the truck if ever needed. He recalls a scene in which Wayne manhandles Casey down a flight of stairs in their house. “I needed to bounce a light in the living room in order to provide enough interior ambiance to balance out the brightness of the exterior seen through the doorway behind the father, so I bounced an 18K in the house, and it practically melted the old house down,” he says. “But I really needed that much fill in order to compensate for how much light was behind the dad.” For virtually all interiors, he manipulated natural daylight and lit with practicals at night, whether it was in the motel where Casey and Jonas seek refuge or in the characters’ homes. For instance, in one scene the only light in the room comes from a TV that Jonas’ depressed mother is watching. “I just used the TV light itself on the actors and moved the TV around for the close-ups to get a bit more out of it. I went through a DVD beforehand and picked scenes that were a little brighter just to get a bit more kick out of the TV light. I also used the orange bug lights out on the patio at night because I was interested in a more discordant or artificial look for the scene where the father and son can’t come to terms,” he says. The scene in which Jonas hides and travels in the back of Wayne’s truck at night was shot in a studio with the use of a swinging light rig. “There were four lights gelled with different colours swinging on each side of the truck – two Kinos and two Peppers – and we were just making the truck vibrate a bit. And we had some fishing line on the flaps to make it look like it was flapping in the wind. And then we took the truck out and did all the exterior shots of the truck driving through similarly tinted light and stitched it together,” Cosens says. “Because we were shooting widescreen, we knew that looking from the back of the truck into the bed of the truck would work so nicely for our 2:40 frame,” he adds. “And then when they stop and the drug deal goes bad, that was just two practical sodium vapour lights to light the bikers and to rake some light into the back of the truck, and then we had a few strobe lights for the gun shots.” For exteriors, he relied on a bit of muslin bounce and negative fill. “It was pretty minimal and a lot of the shots were moving so it wasn’t like I could set up bounces

and just let them live somewhere. The camera’s always moving, so it was hard to just get something up and put it in one place and leave it,” he explains. “A lot of what we did was I worked with Nathan to just structure the scenes knowing where the sun was going to be, so we just played with the sun the MOSS whole time and we were able to move quickly enough that we could situate scenes in the right backlight or sidelight or use the breakup of light through foliage. I think that as you age and get more experience you grow braver and you start to have the confidence to use and manipulate natural light fluidly and to your advantage.” Morlando and Cosens took advantage of the horizontal landscapes, which lend themselves to widescreen shooting, and they took care to keep the camera fluid. “We didn’t want the film to be jagged with loose handheld. We wanted to keep the camera moving but we also didn’t want to be obtrusive; we wanted the focus to be on the kids, and I wanted the journey of the kids to lead us, not the camera,” Cosens says. “And also we were depicting a love story too, so we wanted a bit of grace,” as Casey and Jonas wander the golden fields surrounding their properties getting to know each other. Cosens says Steadicam operator Michael Heathcote was a key asset. “The whole film is Steadicam, and Michael was running through the woods on Steadicam,” he says. “He was definitely part of making it a fluid, floating film. He’s an amazing s camera operator, and he’s got a beautiful eye. He and I just really see the world in a similar way. I could just say, ‘This is the shot,’ and he would just really finesse it. I have so much trust and faith in him and our professional relationship continues to evolve.” Cosens was also mindful of supporting the performances of the young Cam Gear would like actors. “One time, I remember –Josh is to wish everyone a very an amazing actor and he had so much potential – but I could tell he was kind happy and prosperous of nervous, and at one point early in the shoot we were just walking across New Year! a field and I said, ‘You know, man, you’re really doing great work, and I really want you to feel safe.’ That really works; just big brother kind of stuff. And they really respond to that because that’s what actors need to feel ultimately – safe.”

Mr Zaritsky on TV

Michael Savoie csc on Making a Film About Making a Film

Michael Savoie csc

By Fanen Chiahemen

John Zaritsky has been making documentary features for almost 40 years, receiving an Oscar in 1983 for Just Another Missing Kid. Among his prominent works are two films he made about the legacy of thalidomide, a pregnancy drug marketed worldwide in the late 1950s and early 1960s that resulted in thousands of babies born with drastic birth defects. Thalidomide was pulled from the Canadian market in 1962. Zaritsky has now returned with a third documentary on the topic – No Limits, which revisits the same thalidomide victims that he profiled years earlier and explores new angles to the story. Zaritsky turned to his long-time cinematographer and

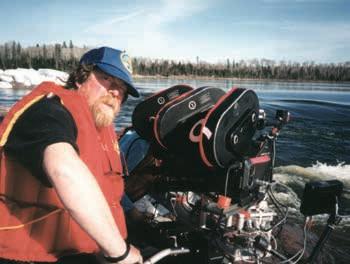

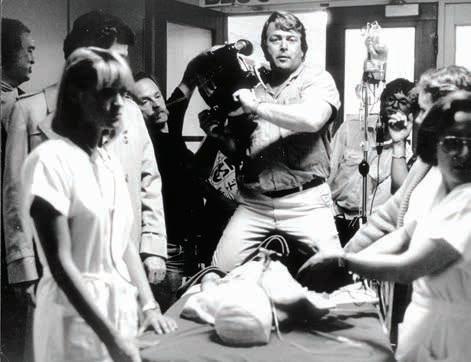

Michael Savoie csc shoots out of a car for Zaritsky’s film No Limits.

collaborator Michael Savoie csc to shoot No Limits, just as Savoie was developing a documentary project of his own about Zaritsky’s career. Savoie was flattered to be asked to work with Zaritsky and says, “John and I had done a lot of work together during the ‘80s and ‘90s, but I was looking for the next film that I wanted to make. I always wanted to shoot the journey of a documentary crew, because that’s the life I’ve led. I started out on the drama sets of the CBC and got into documentary filmmaking and loved it so much, I just never got out of it.” Savoie and his business partner Jennifer Di Cresce then pitched their idea of a documentary film about Zaritsky making a film. documentary Channel agreed to fund the project, and at the same time Savoie agreed to work with Zaritsky on No Limits. As Savoie saw it, it was a perfect opportunity to make his own film, which would be both a portrait of Zaritsky and a candid behind-the-scenes look at documentary filmmaking. “It just seemed to me to be the meeting place where all the various factors that we needed to make a documentary would be in one location. All the players were in one silo together at that point,” Savoie says. The result was the documentary Mr Zaritsky on TV, which had its world premiere at the Whistler Film Festival in December. To handle both projects, Savoie and Di Cresce hired a second cameraperson, Jake Chirico, who would work with Di Cresce shooting the material that would become the spine of Mr Zaritsky On TV. Savoie shot Zaritsky’s No Limits with two Sony PMW 300s. The B camera was operated by his son, David Frank-Savoie. The same camera model and gear were used on Savoie’s Mr Zaritsky On TV “so that everything would have a consistent look,” he says, “although the cameras and data were kept separate.” Over a period of three weeks, both film crews travelled more than 20,000 kilometers through six countries – Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the United Kingdom – with Savoie capturing Zaritsky meeting and interviewing with thalidomide victims for No Limits, while at the same time keeping an eye on the shooting for his own film, Mr Zaritsky on TV. Savoie says Zaritsky put complete faith in him and had no input in the making of Mr Zaritsky on TV. “He and I have been in some very difficult situations in the past, and our lives have been in each other’s hands a few times, so he just trusted me,” Savoie says. The trust between the two filmmakers is evident in Savoie’s documentary, and after working together for so many years, their roles are clearly defined. “John is all story,” Savoie says. “That’s all he concerns himself with; it’s getting the story onto some kind of video format. And that’s what makes him so good. Practical details are not his strongest suit. He doesn’t want to have to arrange hotels or airfare, filling up the car with fuel or anything like that. He always sticks straight to story. And that’s where I come in. I kind of step into the producer’s role which is something that I’ve done with Zaritsky for 25 years, made sure that all the various details are taken care of. That’s really how it works. He takes care of his business, his focus, and I take care of everything else.” As is his habit, Savoie carried with him a large arsenal of lights. “There were some Diva lights, some LEDs, tungsten lights for accent and for little spots. Basically there were a whole bunch of soft lights,” which he would employ according to what the space and the interview subject called for, he says. “When you walk into a situation, whatever it is, you really make decisions as to how you want it to look based on who the character is and what he or she is going to say,” Savoie explains. “I’m also a great believer in available light.” While he takes care of what he needs from a technical standpoint to capture the interview, Savoie says he is always conscious that Zaritsky is establishing intimacy and trust with the subject during the set-up stage. “It’s a foreign experience for the interview subject, and what you have to do is disarm

were looking for those moments when the big cameras weren’t rolling. They were looking for those reactions,” Savoie says. “That’s pure cinema verité shooting; it’s keeping your eyes open and remembering what’s important to you and to the story you want to tell.” When a 77-year-old German woman describes how she felt the moment her son was born with birth defects, the camera stays on Zaritsky, who is listening wide eyed, head shaking, clearly moved by her story. “I had never seen Zaritsky direct before, and we discovered that a lot of what he does is very subtle,” Di Cresce says. “Because a big part of a documentary is trying to get people to open up by conveying empathy. Maybe it doesn’t look like much, but the person who’s being interviewed is looking for those subtle visual cues from the director that convey that they should keep going, that they are to keep revealing themselves and that what they’re saying is good.” As with all documentaries, not everything went according to plan, and early in the process, Zaritsky lost an important interview when the father of one of the thalidomide victims backed out at the last minute. “This really confused things. A major element of [Zaritsky’s] story structure was now gone,” Savoie explains. While Zaritsky goes for a solo walk to process the news, Di Cresce and Chirico’s surreptitious shooting comes into play to get inside the documentarian’s head. “I was in the room when Zaritsky got the call,” Di Cresce says. “And I should add – this sounds terrible – but when things go bad for Zaritsky’s film, it was good for our film because we were looking for those draJohn Zaritsky sits across from interview subject Jan Schulte-Hillen while sound recordist matic moments that revealed his conflict. So we Justin Ladd adjusts the boom mic overhead. Zaritsky prepares for an interview with film had to be very opportunistic when things didn’t participant Moni Einsenberg-Geginat. go their way. When that call came in and John started to put his jacket on, I knew that to hound them with your behaviour, with your eyes and your smile, him with questions in that moment was not going to go very your mannerisms. You have to make them feel comfortable well. So when he stomped off to have that walk, I sent Chirico and confident that they’re going to be well taken care of, and out alone and he was just clandestinely filming John. It wasn’t you have to show yourself to be a nice person,” he says. “I’ve a time for questions; it was a time for just sheer observation been doing it for so long that it’s become second nature to because I don’t think we would have captured John’s real feelme as to how to conduct myself on these interviews. And the ings. I think we would have seen a good face or a courageous same goes for the rest of the crew as well, including Jenniface if he was going to explain what was going on internally – fer and Jake, who were there all the time although they were if he could even articulate his feelings in that moment. more of satellite, off to the side and concentrating on other There is something very safe about relying on people’s selfelements, not so much on the interview subjects specifically” reporting, and it’s not necessarily true reporting. I mean, our Di Cresce and Chirico focused instead on observing own self-reporting is flawed. You have to hope and trust that Zaritsky at work when he was both on camera and off. “They people in the film are going to be demonstrative, and you also

put a lot of trust in your audience that they are going to pick up on the subtlety of what could be happening.” Savoie says Di Cresce and Chirico were always so discreet that “there was never a moment when you felt they were shooting you. They just disappeared, and that speaks to their skills.” As a case in point, in the scene where Zaritsky is processing his disappointment with the loss of the key interview, he seems to be completely unaware that he’s being shot and only notices Chirico with the camera at the end of his walk. Di Cresce reveals that staying out of the way involved “a lot of ducking and hiding behind obstacles” as well as being everywhere all the time. “I spent a lot of time hiding, but most of it, quite frankly, was just a result of being ubiquitous,” she says. “We were there all the time, and everybody was so exhausted that it got to a point where nobody cared anymore and that was just a result of being around the crew and in their faces all the time.” Documentary shooting comes with its fair share of everyday difficulties, and Savoie and his crew did not shy away from capturing Zaritsky’s unpleasant reactions under pressure. “When out on the road like that, it’s really hard, you’re working 20 hours a day, you’re not eating, you’re not sleeping, you’re in some jeep driving all over the place. It’s really exhausting,” Savoie says. “Anybody’s bound to get upset, and John has a particularly sensitive hair trigger; he’s a volatile guy. You’re always paying attention, trying to figure out where he’s at, and when he’s quiet you let him be quiet. A lot of the time, he’d just sit with his headphones on and listen to music to calm himself down.” Still, having worked with Zaritsky for so many years, Savoie says he knows by now how to pick his battles. At one point, he expresses frustration with Zaritsky when the documentarian gets up to use the restroom in the middle of an interview on a day when the crew has been completely pushed to the limit. “That was a battle I was going to pick,” Savoie says. “I wasn’t concerned about me; there were a whole bunch of people there, and all of us were in the same spot. And at that point, excluding John, I’m the guy at the top of the food chain, and it’s up to me to make sure that seven days into the shoot, we don’t end up with a sound man with a head cold. We have to eat; we’ve got to sleep. I’m not afraid to speak up for the crew. And if I say to John, ‘We need to stop and eat because the sound man and the B camera operator are both eating candy for dinner,’ it’s time to stop.” Being on the road so much, Savoie sometimes worried about Zaritsky’s stamina, but he had faith that the director knew how to handle himself, so he never requested a slowdown. “He’s a grown man and he knows what he’s capable of,” Savoie maintains. “John is a tenaciousness guy,” he adds. “I like to think I am as well. I think when John gets an idea in his head of what he wants to do, he does his very best to get that done. I like

Top: John Zaritsky, Michael Savoie csc and sound recordist Justin Ladd share a laugh while travelling in a van. Zaritsky speaks with film participant Louise Medus-Mansell outside her home. John Zaritsky and Michael Savoie csc have been making films together since the ‘80s.

All photos: Jake Chirico, except bottom photo this page: photo courtesy of Michael Savoie csc

to think the same thing washes over into my work now as I have transitioned to taking on extra duties producing and directing. There have been a lot of producers that I’ve worked with along the way, and everybody has their own little trick or their own little hiccup that you can learn from. I think that some of Zaritsky’s single-mindedness has rubbed off on me. But best of all, I learned a lot about storytelling from John.” That’s something Savoie hopes to take with him as he continues to develop his own projects. “I think the days of me working for other people are really coming to an end,” he says. “I want to develop my own ideas, my own stories, and I can also shoot them.” Despite the grind involved in documentary filmmaking, Savoie says, “It’s rewarding. It’s the people that you meet along the way. Those are the really big benefits. You meet people that have so much integrity. It’s a real privilege and you’re grateful for the opportunity. That’s what pushes you out there, that curiosity and just wanting to meet new people, new stories, new ideas, new dilemmas and new crises.”