YEARS

Families

LSUReveille.com

Families

LSUReveille.com

First in a four-part series.

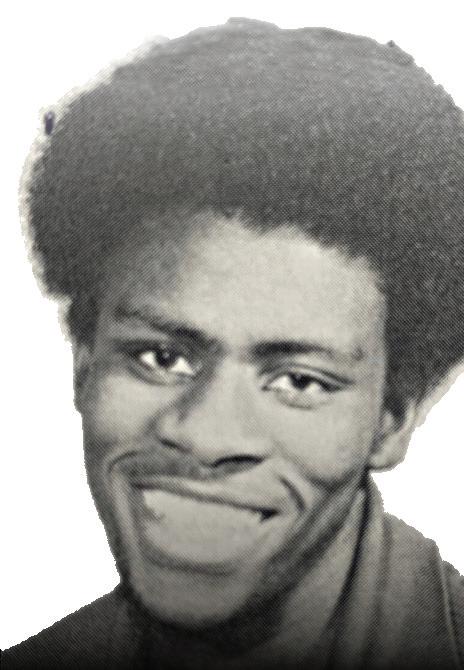

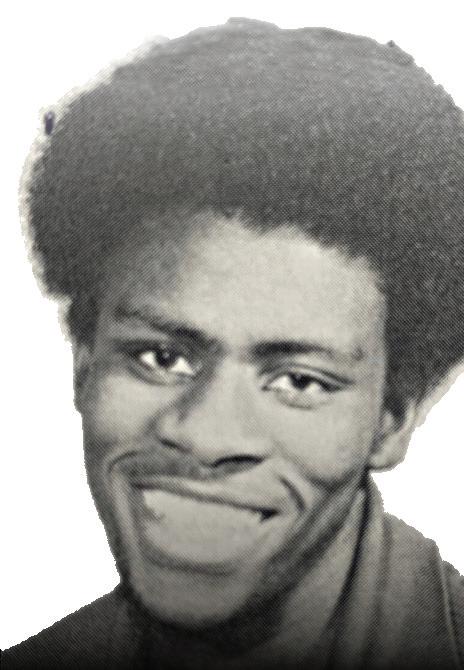

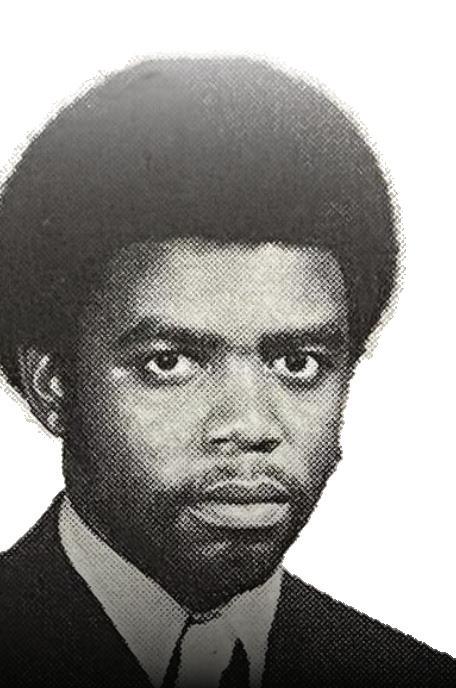

Josephine and Denver Smith took different approaches to pro tests at Southern University in the fall of 1972. Josephine skipped class for meetings, while her older brother stayed away and warned her to be careful.

The pair had grown up with 10 other siblings in a tiny sharecrop per’s house near New Roads, Loui siana, where they picked cotton in the hot sun and harvested pecans to help make ends meet. When they were not working, they fished, swam by the river levee and, not having paper, scratched their mul tiplication tables in the dirt with sticks, the oldest checking the work of the youngest.

Despite their modest finances, one thing was always certain: They would go to college.

One by one, the siblings en rolled at Southern University in Ba ton Rouge. Denver was the third to go, followed by Josephine the next year. And while Josephine lived in a dorm amid the growing campus ferment, Denver – 5 feet, 9 inches and slim – walked each morning to a white-framed Catholic church, where he hopped on a school bus for the hour-long journey southeast to Baton Rouge.

The protests at Southern in Oc tober and November 1972 echoed what was happening around the United States in an era of civil rights and anti-war activism. South ern—the main campus in a uni versity system that had the larg est number of Black students in the country—had its own history of activism that began with lunch counter sit-ins. By 1972, many of its 9,000 students in Baton Rouge were tired of what they saw as poor funding and teaching, dilapidated buildings and a lack of responsive ness to their concerns.

From those frustrations came weeks of protests, class boycotts and demands for a change in the school’s leadership. Rather than sticking with negotiations, univer sity officials repeatedly summoned sheriff’s deputies and state troop ers onto campus—and a standoff between roughly 150 students and 85 heavily armed officers that Nov. 16 ended in tragedy.

Amid the chaos and tear gas, a single blast of buckshot fired by a deputy from the East Baton Rouge Parish Sheriff’s Office killed two 20-year-old men in a stream of flee ing students.

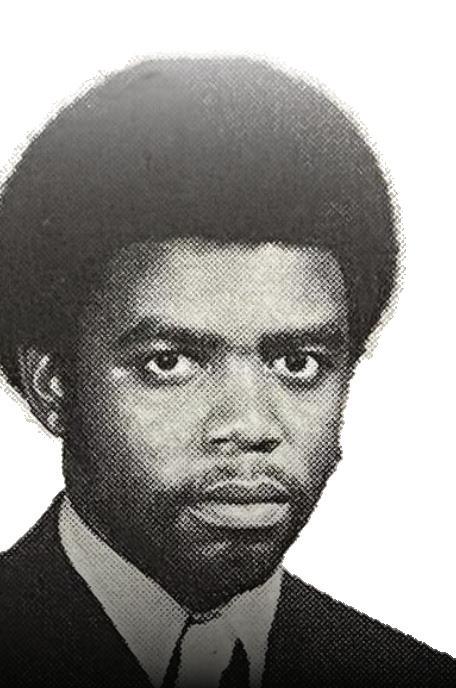

One was Denver Smith, who may have just wandered into the crowd to make sure Josephine was safe. The other was Leonard Doug las Brown, a junior who had fin ished breakfast with his girlfriend and went out to see why the crowd had gathered.

Neither man had been involved in the protests, and it was never

determined which deputy fired the shot.

Now, as the 50th anniversa ry of the shooting approaches, a 10-month examination by the LSU Cold Case Project provides a much clearer picture of one of the most troubling episodes in race relations in Baton Rouge—and one that still resonates nationally amid the tense relations between police officers and young Black men.

This series is based on dozens of interviews with family members of the victims; student leaders and witnesses; and former sheriff’s dep uties, FBI agents and prosecutors who had never discussed the case publicly.

Researchers from LSU’s Manship School and the Southern Univer sity Law Center also studied nearly 2,700 pages of FBI documents that reveal how agents quickly nar rowed their search to a handful of deputies but could not prove who fired the fatal shot.

A gubernatorial commission created shortly after the shooting determined there was “no justifica tion” for it and that the confronta tion “should never have happened.”

The commission, headed by Wil liam J. Guste, who was then Loui siana’s attorney general, found no evidence that any of the students was armed.

It also concluded that Southern officials were not prepared to cope with student unrest, criticized pro testers for disrupting classes in the weeks leading up to Nov. 16 and chastised law enforcement officials for responding with more force than was needed.

“No one should have pointed a gun at those students,” Mike Bar nett, who was at Southern that day as a young sheriff’s deputy and is now a liaison to the Louisiana Sher iff’s Association, said in a recent interview.

“There was no threat from them or anyone else at the time the shot went off,” he said.

Challenging the “Old Guard”

In the spring of 1972, a group of Southern students drove to a na tional Black political convention in Gary, Indiana. Among them were Fred Prejean and his girlfriend, Ola Sims.

Prejean was a tall, talkative 25-year-old political science major who had returned to his education after years in community activism. At 17, he had been inspired hear ing the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. speak at the March on Washington. He also was struck by how casually people of different races intermin gled in the march’s crowds.

Sims was a 19-year-old psychol ogy major who grew up in north Louisiana near Grambling State University, another historically Black institution. She had accept ed a scholarship to Southern for a program in the psychology depart ment, wanting to experience some thing new.

The conference in Gary, aimed at electing more Black people to of fice, sparked a new connection to politics in Sims—one that took hold of her that fall when a young pro fessor, Charles Waddell, resigned as chairman of Southern’s psychology department.

Waddell was beloved by his stu dents—and was everything they did not see in Southern President George Leon Netterville Jr., a quiet 66-year-old with white hair and dark-framed glasses.

Waddell was frustrated by a lack of equipment for his research. He took his concerns to Netterville, who had started as Southern’s busi ness manager in 1932 before being promoted to its vice president for finance and becoming Southern’s third president in 1968.

Netterville promised things would improve. But in meeting af ter meeting, they did not, and on Tuesday, Oct. 17, Waddell informed his student she was leaving.

Around midnight, a group of students braved the dark to pro test outside Netterville’s home, and he came out briefly to try to calm

them.

But to the students, Sims said, a consensus was forming that Nett erville was basically an “old guard” administrator who followed “oldguard rules” – and they were go ing to have to keep pushing if they were going to see any change.

Tensions rising on both sides

Sims brought Prejean to a meet ing organized by the psychology students, who soon realized that students in other departments shared their concerns.

Students noted that LSU’s main campus in Baton Rouge spent $2,325 per student, while Southern spent only $1,327 per student, and that their school was losing faculty to better pay elsewhere.

“The conditions on the campus overall were not comparable or even close to the conditions that existed at LSU,” Sukari Hardnett, one of the protest leaders, said re cently. “And it wasn’t fair.”

As student talk bubbled, a loose organization formed.

The group, called Students Unit ed, argued that Southern was fail ing to serve the Black community. Members put together a long list of grievances, ranging from substan dard housing and pest problems to no emphasis on the Black experi ence anywhere in the curriculum.

They thought that part of the solution might be a council system that would allow faculty and stu dents voting power over university decisions, and they wanted Netter ville to resign.

The students delivered the grievances to Netterville on Oct. 23, at an assembly the next day in the Men’s Gymnasium, he agreed to some student involvement in uni versity oversight. But the meeting fell apart when it became clear that he did not intend to step down, and the tactics escalated on both sides.

Worried about how the stu dents might react, Netterville had arranged for 100 sheriff’s depu ties to be on standby at the Baton Rouge airport. Black sheriff’s depu ties in plain clothes walked around campus watching for any signs of trouble.

Shortly after the meeting ended, an estimated 1,000 students de scended on the state Board of Edu cation and the Capitol, with some marching the seven miles from campus and others driving.

Gov. Edwin Edwards, a Demo crat who had taken office eight months earlier with Black support, stepped outside to meet them. Ed wards refused to consider Net terville’s resignation. But he told the students he would negotiate on other issues if they returned to school.

The next day, Oct. 24,protest leaders met in the Southern gym. They decided to call for a boycott of classes, giving speeches outside the dorms to rouse support.

“You got to be careful”

The surge in activism caught

B-16 Hodges Hall

Louisiana State University

Baton Rouge, La. 70803

(225) 578-4811

Editor-in-Chief

JOSH ARCHOTE

Digital Managing Editor

HANNAH MICHEL HANKS

Digital Editor

JAYDEN NGUYEN

News Editor

BELLA DARDANO

Deputy News Editor

DOMENIC PURDY

Sports Editor

PETER RAUTERKUS

Deputy Sports Editor

MACKAY SUIRE

Entertainment Editor

AVA BORSKEY

Opinion Editor

CLAIRE SULLIVAN

Multimedia Editor

MATTHEW PERSCHALL

Production Editor

MADISON COOPER

Chief Designer

EMMA DUHE

(225) 578-6090

EMILY TRAN

Layout/Ad Design

SOFIA RAMOS

The Reveille holds accuracy and objectivity at the highest priority and wants to reassure its readers the reporting and content of the paper meets these standards. This space is reserved to recognize and correct any mistakes that may have been printed in The Daily Reveille. If you would like something corrected or clarified, please contact the editor at (225) 578-4811 or email editor@lsu.edu.

The Reveille is written, edited and produced solely by students of Louisiana State University. The Reveille is an independent entity of the Office of Student Media within the Manship School of Mass Communication. A single issue of The Reveille is free from multiple sites on campus and about 25 sites off campus. To obtain additional copies, please visit the Office of Student Media in B-39 Hodges Hall or email studentmedia@ lsu.edu. The Reveille is published biweekly during the fall, spring and summer semesters, except during holidays and final exams. The Reveille is funded through LSU students’ payments of the Student Media fee.

The Student Government Sen ate on Wednesday unanimously passed a resolution “strongly con demning” LSU President William Tate IV for the Building Name Evaluation Committee’s disband ment.

The resolution, authored by senators Adam Dohrenwend, Cooper Ferguson and Chloe Ber ry, urges the university to follow through on 2017 and 2020 resolu tions to have buildings with prob lematic namesakes renamed.

The university’s building re naming committee came to a con sensus to disband in December 2021, according to a letter sent to Tate on behalf of the committee.

The letter said the committee dis banded to “give the new adminis tration adequate time to develop its vision and set priorities.”

The committee’s dissolution came less than a month after Tate said that he would have never started the committee in the first place, had he been president at the time. He said then that he’d rather pursue other avenues to increase diversity and inclusion at LSU.

The resolution says Tate was undermining the objectives of the committee before they were dis banded, concealed the commit

tee’s disbandment for 10 months, did not set the renaming of these buildings as a priority and dis missed the concerns of the student body.

Tate released the following statement to The Reveille regard ing SG’s condemnation:

“In the months since the build ing renaming committee voted to disband itself, I have been working

to outline priorities related to di versity and equity for our campus,” Tate said. “This included a reorga nization of our diversity efforts into the Division of Inclusion, Civil Rights & Title IX and conducting a national search that resulted in the hire of Todd Manuel as vice presi dent over the division.”

“The administration has also been considering a number of oth

er ways to enhance our diversity efforts such as pathway programs to help provide more opportuni ties to students from elementary school to Ph.D. levels, diversity hiring initiatives, and our A&M agenda with Southern University,” the statement continued. “Impor tantly, we are working to find ways to better acknowledge important pioneers who came before us,

and we will be finalizing and roll ing out new efforts in the coming months.”

International trade and finance junior Cooper Ferguson, a senator for UCAC, said previous resolu tions had been made in 2017 and 2020 to change these building names, with little progress being made.

“There’s been one large student movement that has been taking over,” Ferguson said. “It’s tearing down the names of segregation ists, slave-owners, confederates, and mass murderers. And you see the inaction from administration on this issue.”

The resolution says the build ing names sanitize people who en acted racial terror during Jim Crow and the Civil War and that certain building names are symbols of racial oppression and work to en force a white power structure.

“White supremacy, symbolic or structural, must be rooted out of all facets of campus life and soci ety at large,” the resolution says.

The resolution says that the building renaming committee was a result of years of students orga nizing around the issue.

“President Tate will not meet with the student-body on this is sue. He feels like he’s not respon sible to the student-body on this issue,” Ferguson said.

Over 1,600 students voted in the fall Student Government senate elections, with two ref erendums failing to pass among seat changes, election commis sioner and psychology junior Chris Charles announced Friday.

The referendum to raise the SG fee by $1.50 ultimately failed to pass, with 560 in favor and 768 against. This fee would have gone on student’s fee bills and would have increased the SG budget.

Another referendum, this one to raise the student me dia fee by $2.75, also failed to pass, with 596 in favor and 736 against. This would have increased the budget for student media, being divided evenly between The Reveille, TigerTV, KLSU and The Gumbo.

The election was held 7:30 a.m. on Wednesday through 7:30 a.m. on Thursday, accord ing to Charles. When compared to previous election turnouts, he said that this election drew more voters than last fall’s election’s 1,200 votes, but sig

nificantly fewer votes than last spring’s election’s nearly 7,200 votes.

Economics and political science senior Rehm Maham, a justice in SG’s judicial branch, said most students don’t vote in the fall elections because there isn’t a flashy presidential race going on like in the spring.

“But [the elections] matter because half the Student Sen ate is up for election,” Maham said. “The Student Senate is the body that is most often trying to change the direction of cam pus.”

There were a total of 96 candidates on the ballot, but two withdrew. Twenty-three were disqualified, largely for not turning in their campaign finance forms, according to Charles. Most of the disqualified candidates were running under the University Center for Fresh man Year. Two types of seats were up for election: a full seat serving for two semesters, and a half seat serving for one.

Here are the winners by college and the ticket they ran under:

College of Agriculture

Full seat winners:

• Crockett Comeaux (Ambition)

• Alex Foret

• Half seat winner:

• Zoe Davis (Fuse)

College of Art & Design

Full seat winner:

• Harris Quadir (Click Here)

E.J. Ourso College of Business

Full seat winner:

• Cooper Ferguson (Click Here)

Half seat winner:

• Joshua Miletello

College of Coast & Environ ment

Full seat winner:

• Paris Holman

College of Engineering

Full seat winners:

• Gabriella Fontenot

•

• Kendal Frazier (Fuse)

•

• Hamood Qureshi (Fuse)

•

• Colin Raby (Fuse)

Graduate School

Full seat winners:

• Prakash Dangal

• Terry Geraldsen (Grad Gold)

• Cullen Hodges (Grad Gold)

• Jocelyn Wood

College of Human Sciences and Education

Full seat winners:

• Gabrielle Farrar (Fuse)

• Emily Herrera (Ambition)

Half seat winner:

• Erica Giambrone

College of Humanities and Social Sciences

Full seat winners:

• Tabari Bowser

• Amelie Chadwick (Ambition)

• Taylor Myers (Ambition)

• Lailah Williams (Fuse)

Half seat winner:

• Jahi Palmer-Davis (Ambition)

Law School

Full seat winner:

• Samantha Jacobsen

Manship School of Mass Com munication

Full seat winner:

• Katherine Melancon (Fuse)

Half seat winner:

• Cortlyn Roddini

College of Music and Dramat ic Arts

Full seat winner:

• Sam Staggs (Fuse)

Full seat winners:

• Presley Gilbert (Ambition)

• Saad Tanveer (Fuse)

University Center for Advising and Counseling

Full seat winners:

• Danielle Jackson

• Taylor Jarrell (Ambition)

• Vivi Nguyen (Fuse)

Half seat winners:

• William Brual (Ambition)

University Center for Fresh man Year

Full seat winners:

• Zachary Broussard (Fuse)

• Brandon Dixon

• Ethan Elmer (Fuse)

• Ryan Griffin (Ambition)

• Lavar Henderson (Ambition)

• Anna Kate Jackson (Fuse)

• Andrew Jewell (Ambition)

• Charles Robertson (Fuse)

• Brandon Turner (Ambition)

• Mallory Urban

• Kelsey Womack (Fuse)

the attention of Josephine Smith, a 19-year-old education sophomore, who was concerned by Southern’s lack of a Black studies program.

“I had never been in a group or organization that was so big – big ger than me – as far as a cause,” Josephine recalled recently. “And I felt led to join that cause for a good reason.”

Denver did not share his sister’s feelings, mirroring concerns from some students that the protests would interrupt their education.

A junior studying computer sci ence more than a decade before the internet, Denver preferred to keep his head in his studies and encour aged Josephine to do the same. He often stopped by her dorm to check on her and her suitemates.

“You got to be careful,” Denver told her.

Denver had almost left South ern after receiving a job offer from a technology company in Houston. But he had declined it that summer after his mother suggested he fin ish his education.

Leonard Brown, a 5-foot-10inch vocational agriculture educa tion major known as Doug, also was focused on his studies, and he returned home to Gilbert in north east Louisiana for two weeks to avoid the protests.

Brown had loved living on a farm as a child. He attended South ern with the help of an educational

opportunity grant and joined the National Society of Pershing Ri fles, a military honor society that focused on developing leadership skills.

Brown also had an infant daugh ter, who lived with his mother, and he went home every weekend to visit them. His sister Evelyn Turner said he hoped to get married and start a farm after graduating.

Negotiate or confront with force?

As the protests churned forward through late October, the students stuck to their demands that Netter ville leave and for a say in running the school—and Gov. Edwards and Netterville would not give in on those points.

The men’s gym became the cen ter of student organizing as well as student-led classes and tutoring.

It was exhausting, said Sims, who married Prejean in 1974. In an interview in her Lafayette home, she recalled that amid the boycotts and late nights, her normally high GPA dropped. She left class quickly one day, embarrassed, after realiz ing she had been so busy she had forgotten to wash her clothes.

When students gathered in the gym on Tuesday, Oct. 31, a school official told them that the meeting was unauthorized. They headed over to the administration build ing, where Netterville refused to meet them. Instead, he called in the sheriff’s deputiesand canceled classes until Monday, Nov. 6.

It is not clear how much say Netterville, who died in 2000, had at this point, with Edwards and an all-white state education board heavily involved. But judging from how two other historically Black universities had handled similar situations, there seemed to be a choice between further negotiation and the risks involved in relying on law enforcement to quell the pro tests.

At Howard University in Wash ington, D.C., in 1968, administra tors negotiated as 1,000 students occupied the administration build ing for four days. The school re fused to fire its president, but the protests ended peacefully after it agreed to incorporate Black history and culture into its curriculum and give students input in its disciplin ary process.

But in Jackson, Mississippi, in 1970, police killed two protesters at Jackson State. The students were fed up with whites driving through campus shouting racial slurs and throwing bottles, and the students were throwing rocks at the cars.

Any hopes for a compromise at Southern evaporated on Nov. 1, 1972, when 150 students at South ern’s campus in New Orleans oc cupied its administration building and demanded the resignation of their president, who left eight days later.

Students at Grambling also made demands on Nov. 1, and the next day, roughly 150 of them bar

ricaded the street outside its ad ministration building with chairs and tables from the dining hall and threw rocks through dorm win dows.

These incidents –as well as a shootout on North Boulevard ear lier that year that had left two Ba ton Rouge police officers and two Black Muslims dead –also had un nerved many whites and placed law-enforcement officers on edge.

Several Southern protest lead ers said in interviews that they cau tioned students not to take control of buildings.

“Whenever we had a demon stration and law enforcement came on campus, we urged the students to go back to their dorms, leave the campus, do not engage the police, do not allow them to engage you,” said Herget Harris, an electron ics technology major and Students United leader.

When school reopened on Nov. 6, Brown’s mother asked if it was safe to return. His sister said he re plied that it must be, since classes were resuming.

About 500 students met in the men’s gym around 10 a.m. that day, and the leaders urged them to keep boycotting classes. State Police and sheriff’s deputies sealed off campus but had no confrontations with stu dents. They left after half the crowd returned to class.

Students United slammed the university at a press conference for bringing police onto campus, and

members of the physics department condemned the “senseless” choice.

“Expect trouble tomorrow”

Over the next several days, a mysterious fire broke out at South ern’s Horticulture Barn, and some students protested on the field dur ing a football game. Harris said Stu dents United did not condone these activities, but Netterville asked for arrest warrants to be drawn for Har ris and seven other student leaders, including Prejean and Hardnett, for disrupting university operations. After some of the students were ar rested, Netterville said the remain ing warrants would not be execut ed if the disruptions stopped.

But the boycotts continued, and on Nov. 15, university and law en forcement officials met at the East Baton Rouge Parish Prison to de cide whether to execute arrest war rants for the rest of the leaders. According to an FBI interview with Sheriff J. Al Amiss, they discussed “whether this arrest of students would stir up trouble and add to the unrest already existing on the campus.”

Still, they decided to execute the warrants. And that evening, Netterville left a message for Gov. Edwards saying that he expected trouble the next morning.

Drew Hawkins, Maria Pham, Allison Allsop, Alex Tirado, Adrian Dubose, Oliva Varden, Cayli Pham, and Brea Rougeau contributed re porting. This series is supported by the Data-Driven Reporting Project.

When one thinks of college football, they may think of the ac tual football on the field, bands or student sections. A small minority of people think about the mas cots. Since the early days of play ing the mascot matchup in college football games, I have been in trigued by mascots.

Mascots bring with them a level of tomfoolery that is an add ed bonus to the already amazing games on the court or field. Take Chip, Colorado’s mascot, playing solitaire on the sideline this sea son while his team was down 4510. You could also look to Puddles the duck, Oregon’s mascot, during College Gameday. He set up his own booth behind the broadcast booth. These mascots all try to make the game fun and entertain ing for fans.

In the spirit of Halloween, we are going to be ranking the top five scariest college mascots.

I will be rating each mascot on three things: Fit check, spooki ness and how likely they are to be seen standing creepily outside your window at night.

No. 5: Clemson Tiger (Clemson)

While most games he is seen wearing a Clemson jersey, the Clemson Tiger is rarely seen wear ing pants. He gets a four in the fit check ranking. The tiger’s eyes are meant to be vicious and creepy.

This tiger’s eyes look glazed over giving it an extra spooky rating (8/10). This tiger is creepy, and if I saw it staring at me from outside my window, I would pee my pants (10/10).

No. 4: Oski (California)

Oski is a lovable bear who wears a lovely California jacket to all games he attends. He pairs that with some amazing pants un like the tiger. Oski is a 9/10 in the fit check. The spookiness of Oski comes when you see the perma nent smile left on his face. It’s om

inous, it’s creepy, and it makes me think about the crimes Oski has committed (8/10). The smile alone would creep me out, but I would check behind you, reader, as he might be behind you…. (10/10) No. 3: Big Red (Western Ken tucky)

Big Red from Western Ken tucky is just a red blob. I don’t even know how it relates to be ing a hilltopper. Zero on the drip scale for wearing no clothes. However, Big Red scores a 10 on the spookiness factor. It’s so omi

nous, and it could easily devour you. Big Red wouldn’t be seen outside your window. It would be sprinting dead at you toward your window (10/10).

No. 2: Providence Friar (Provi dence)

The Providence friar, I’m scared just writing that. The deep chilling look in its eyes, the haunt ing smile and the black cape. The friar has definitely committed some major crimes in its lifetime. And it’s not stopping there. It’s coming for you… 8/10 on drip, 10/10 spookiness and 10/10 win dow runner.

No. 1: Purdue Pete (Purdue)

Out of all the mascots that ex ist in college, Purdue Pete takes the cake for the Halloween spe cial. He rocks the team fit as well as a hammer to commit various crimes on and off the field. He gets a 10/10 for the fit check. Pete also is absolutely terrifying to look at.

His deep stare in his eyes, creepy smile and big head bring nightmares to opponents. 10/10 for spookiness. Lastly, as some one who went to Purdue, I have seen Purdue Pete outside of my window once and it was the inspi ration for the last category to this. I was so scared, I almost cried.

And there we have it, the scari est mascots in college. Be on the lookout this spooky season for one of our creepy, yet lovable friends.

TRE ALLEN @treday0314

TRE ALLEN @treday0314

LSU’s offense has been click ing these past couple of weeks, mainly because of Jayden Dan iels.

There were a lot of ques tions and debates surrounding the quarterback spot for the Ti gers between Jayden Daniels, Garrett Nussmeier and even the freshman Walker Howard.

So far, it’s been the right move to go with Daniels. The 6-foot3, 200-pound quarterback has led his team to a 6-2 record and a No.15 ranking. He started off slow as the passing game was stagnant, but these past couple of games against Florida and Ole Miss, he’s shown how good of a passer he can be by throw ing for a total of 597 yards and five passing touchdowns.

His passing ability has im proved, he has been taking his time and reading the defense and finding the open receiver. He has also been giving his re ceivers chances to go up and make plays by taking downfield

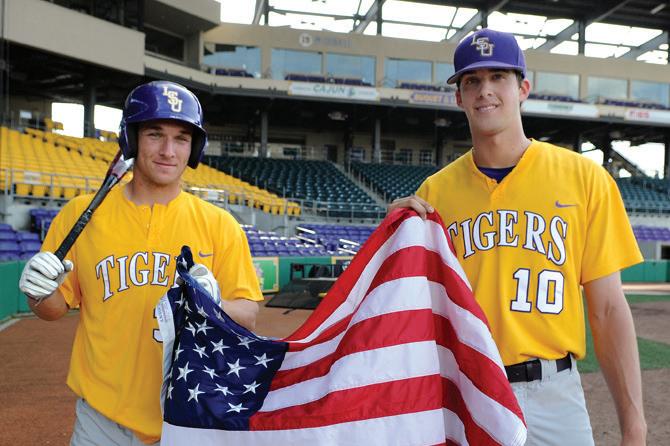

This year’s rendition of the Major League Baseball World Se ries sees two former LSU baseball players competing for a champi onship.

Former LSU All-Americans Aaron Nola of the Philadelphia Phillies and Alex Bregman of the Houston Astros are facing off in this year’s World Series. Nola, a right-handed pitcher who is a Ba ton Rouge native, and Bregman, a third baseman from Albuquer que, New Mexico were once wear ing the purple and gold together as teammates in 2013 and 2014. They were critical in the Tigers’ drive to the 2013 College World Series.

Former LSU baseball players have played for World Series par ticipants on 43 occasions and on 19 occasions were a part of cham pionship teams. Outfielder An drew Stevenson is LSU’s most re cent World Series champion as he played for the Washington Nation als in the team’s 2019 World Series

run. That year, the Nationals beat Bregman and the Astros in seven games to win the organization’s first World Series championship Nola, a 2018 National League All-Star, helped lead Philadelphia this season to its first postseason appearance since 2011 and its first World Series berth since 2009. He recorded an 11-13 mark and a 3.25 ERA in 205 innings during the 2022 regular season with 29 walks and 235 strikeouts. This season, Nola recorded the most strikeouts with fewer than 30 walks in Major League Baseball history.

Nola is Philadelphia’s No. 2 starter and has collected wins in the postseason over the St. Louis Cardinals in the Wild Card Series and over last year’s World Series champions, the Atlanta Braves, in the Division Series. The pitcher was the Phillies’ first-round draft choice back in 2014 and is now in his eighth MLB season.

Nola enjoyed a monumen tal three-year (2012-14) career at LSU, recording a 30-6 record

DANIELS, from page 9 shots. Daniels’ passing ability has been forcing people to take notice and quiet his doubters. Something that has also helped his performance has been his running ability. Al though Daniels has a tendency to have a run-first mindset, it’s been something that has won LSU many games this year. He has broken the record for most rushing yards in a season by an

LSU quarterback with 524 yards so far and the most rushing touchdowns in a season by an LSU quarterback with nine. Questions about the LSU of fense were something that many fans have been talking about, discussing how it was going to hold the Tigers back from any major success, but with help of play calling and overall better performance by Daniels, the Ti gers have confidence going for ward.

MLB, from page 9 and a 2.09 earned run average in 332 innings with 345 strikeouts. He was a two-time first-team AllAmerican and is the only pitcher to win the SEC Pitcher of the Year award twice, receiving the honor in both 2013 and 2014.

Bregman, who won the 2017 World Series with the Astros, helped lead the Astros to the American League pennant in a 4-0 sweep over the New York Yan kees. He helped guide the orga nization back to the world series for the fourth time in six seasons. The two-time American League

All-Star and 2019 Silver Slugger Award winner batted .259 during the 2022 regular season with 38 doubles, 23 home runs, 93 runs batted in and 93 runs scored.

Bregman was drafted as the No. 2 overall pick in the 2015 MLB Draft and is now in the height of his seventh season with the As tros. He recorded a .333 batting average, going for 5-for-15 in Houston’s Division Series sweep of the Seattle Mariners with one double, one home run and three runs batted in. Bregman also hit a .333, going 5-for-15 in the ALCS with one double, one home run and four RBIs.

Bregman has hit 14 home runs and registered 43 RBIs in 80 career MLB postseason games, marking the most postseason home runs by a third baseman in MLB history.

Although he’s a third base man in the majors, Bregman played shortstop at LSU from 2013 through 2015 and led the Tigers to two appearances in Omaha for the College World Series. He was a two-time first-team all-Ameri can for the Tigers. Bregman was named the recipient of the 2013 Brooks Wallace Award as the na tion’s best shortstop for his ef forts.

Must be an LSU student enrolled half-time at minimum and in good academic standing with a minimum of

One of the simplest but most profound observations by Edmund Burke, the founder of modern con servatism, is that history doesn’t stop: Society has never and will never be perfect, and things in evitably evolve with the passage of time.

The role of the conservative, then, isn’t to fight a losing battle, to resist change simply because change is bad. Instead, Burke ar gued that it’s the role of the conser vative to preserve the good things – the true things – and especially institutions, which help protect the rule of law and are the factories of a nation’s social and cultural val ues.

An integral and necessary part of this preservation is an histori cally accurate understanding of these institutions. Possessing such knowledge, however, is difficult –especially in today’s United States, where hyper-partisanship makes understanding the most basic of facts laborious.

Take the American founding, for example. Since its creation, pol iticians, pundits and scholars have debated the intentions and purpose of the Constitution: Was it created to perpetuate slavery? To establish a Christian nation? To protect indi vidual rights?

At a recent Turning Point USA talk, at LSU on Tuesday Jeff Landry,

Louisiana’s Attorney General and a Republican candidate for gover nor, brought his answer to LSU’s campus: It’s clear, Landry thinks, that the United States is Christian through and through – and that it needs to rediscover its religious foundations.

There’s been an improper switch, Landry argued, in our country’s source of truth and val ues. While under the Founders’ watchful eyes, it was God – “Big G” Landry said. But now, because of the machinations of an historically corrupt court system, it has de volved into the government – “Little g,” he said.

According to Landry, the sepa ration of church and state is a myth. The “wall of separation” between government and religion as articu lated, for instance, in the Supreme Court’s 1947 Everson v. Board of Education decision, was never what the founding fathers meant when they penned the Bill of Rights.

For Landry, this is a convenient argument – one that plays well to his Trump-friendly, Protestant Evangelical base.

Question: If God and Christian ity are on Landry’s side, who could stand against him? Answer: the truth.

While some of the founding fa thers were practicing Christians, many of the most important names – Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, James Madison, Alexander Ham ilton – weren’t. They were deists who believed in an impersonal, cre ating force of the universe that was wholly unconcerned with human

affairs. Mankind was left to his own devices and was thus reliant on his reason, his own personal, rational faculties, a philosophical Jiminy Cricket, to lead him.

Jefferson, who is credited with writing the Declaration of Inde pendence, turned to Enlightenment philosophy, rather than Christian ity or the Bible, as the theoretical backbone for America’s first and most important documents.

Most specifically, Jefferson in corporated the 17th-century Eng lish philosopher John Locke in three important ways.

First was Locke’s emphasis on reason – which Locke said was “our only star and compass,” a most trusted guide. Second was Locke’s articulation of natural rights: that men were born with certain, in alienable rights upon which no government could rightly infringe. Third was the three most essential and basic of these rights – life, lib erty and property – which Jefferson famously reformulated into life, lib erty and the pursuit of happiness.

Interestingly, God is largely left out of Jefferson’s equation. Which doesn’t mean that there’s no room for conversations about God or the role of Christianity in the Ameri can founding (New England Puri tans would have something to say about that), nor does it mean that individuals are required to aban don their beliefs when entering the public square. But it does indicate that making claims for an explic itly Christian Constitution or Bill of Rights is dubious at best.

This areligious interpretation of

REAGAN COTTEN / The Reveille Attorney General of Louisiana Jeff Landry addresses the room on Oct. 25, in the Student Union in Baton Rouge, La.

the American founding is corrobo rated by several scholars, perhaps most importantly Thomas West and his “The Political Theory of the American Founding,” where he argues that the founders indeed meant for the Constitution to be a Lockean natural rights document as opposed to one based on com mon law, natural law, Christianity or classical republicanism.

According to LSU political science professor James Stoner, this means that the intent of the American government is to protect people’s rights from tyranny and arbitrary rule. Noticeably, it’s not to perpetuate Christianity or any other faith. In fact, Christianity is only compatible in American gov ernment once it has been purged of anything that may contradict with natural rights.

If West’s argument is accurate, Landry’s view of the Constitution, Bill of Rights and, by extension, its

courts, simply can’t be true.

Landry’s talk did have many conservative elements: He recog nized that the United States and it’s traditions are good true and worth fighting for; he rightly identified some of the excesses of the Ameri can left and the dangers they pose; and he emphasized the importance of personal responsibility.

But if Landry wants to fully embody traditional American con servatism (one might assume he would, given his claims to origi nalist readings of the Constitution and his legal credentials as attorney general), he needs to reevaluate his historical interpretations of Ameri can and its founders.

Otherwise, in the conservative view, Landry’s perspective is coun terproductive and the antithesis of Burke’s description of the con servative vocation: to preserve a nation’s institutions in accordance with history. Landry’s current posi tion is one that is only nominally conservative and in actuality seeks to arbitrarily change the most es sential of American political facts.

If Landry doesn’t want to ad mit his true stance, however, and he truly does want to advocate for a redefinition of America along the lines of mainstream Trumpian, Protestant Evangelical lines (a curi ous thing to do for a Catholic), then fine. He’s entitled to that opinion. But he should at least be honest enough to come out and say it.

Benjamin Haines is a 24-yearold history graduate student from Shreveport.

Lakers guard Russell West brook has come under fire for his recent atrocious performances, rekindling a discussion about ath letes and heightened criticism in the social media era.

When the Lakers play, West brook often trends on Twitter for all the wrong reasons. He usually trends under both his name or his nickname, “Westbrick.” “Brick” is a term in basketball meaning an ugly missed jump shot.

The former MVP is now a washed-up bricklayer who can’t be bothered to attempt to play de

fense 90% of the time. Every time he shoots, people in the arena peo ple behave as if they’re witnessing a horrific car accident. He’s the pri mary reason for his team’s strug gles and in all likelihood will be traded soon.

Despite this, Westbrook has remained composed in a situation that would crush most people. Be ing ridiculed online, turned into a punchline and universally de spised by a massive fan base for ruining their team and staining the legacy of their franchise is a tough tide to remain stable under.

The general populace wouldn’t be able to stand such scrutiny.

If the internet pilloried teachers when one of their students failed a standardized test, calling for them to be traded to another school

district, they wouldn’t be able to handle it. The negativity would be crushing.

Imagine if a server at a restau rant became the target of an online attack campaign whenever they got an order wrong. They wouldn’t hold up under the pressure. They’d come home from work to open their phone to find that while they were at work their critics have come up with new names to belit tle them. They’d start to lose con fidence.

Picture a world where NASA en gineers were lambasted every time they came into work a little late. They wouldn’t be able to stand it. Westbrook detractors would say that these comparisons are not comparable because of how bad Westbrook is playing. They may

say that his performances would be more akin to a teacher who scrolled through Instagram all year in place of any instruction or a server who accidentally burned down his restaurant or the engi neers that worked on The Chal lenger.

This point may be true, but it doesn’t negate the value of basic human decency. Being one of the most detrimental players in NBA history shouldn’t make someone a villain. Society would benefit from a collective understanding that sports ultimately don’t matter.

They’re fun to watch, analyze and predict but that’s all it is: fun. If the Lakers lose every game this season, it won’t meaningfully af fect their fans’ lives. But you wouldn’t know that by looking at

their tweets.

There’s no need to contribute to the social media hate storm. When confronted with another in evitable vomit-inducing Westbrook performance, Lakers fans should remember to treat him with re spect. He has shown resilience by not lashing out at any fans, but he shouldn’t have to deal with that.

Many athletes read their men tions, so any disgruntled social media users should keep that in mind when they post. Everyone would be better off if social media was a more positive place. Save the negativity for articles in the school newspaper.

Frank Kidd is a 21-year-old mass communication junior from Springfield, Virginia.

The Reveille (USPS 145-800) is written, edited and produced solely by students of Louisiana State University. The Reveille is an independent entity of the Office of Student Media within the Manship School of Mass Commu nication. Signed opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the editor, The Reveille or the university. Letters submitted for publication should be sent via e-mail to editor@lsu.edu or deliv ered to B-39 Hodges Hall. They must be 400 words or less. Letters must provide a contact phone number for ver ification purposes, which will not be printed. The Reveille reserves the right to edit letters and guest columns for space consideration while preserving the original intent. The Reveille also reserves the right to reject any letter without notification of the author. Writers must include their full names and phone numbers. The Reveille’s edi tor in chief, hired every semester by the LSU Student Media Board, has final authority on all editorial decisions.

Barbara Jordan Congresswoman“If you are dissatisfied with the way things are, then you have got to resolve to change them.”