11 minute read

UPDATES FROM LUNCH LADY

Advertisement

CHILD NUTRITION WORKERS MAKE SURE AKRON STUDENTS EAT, EVEN WHEN THE JOB PUTS THEM AT RISK

REPORTING, WRITING AND PHOTOS BY H.L. COMERIATO

The chocolate milk is a hit. From kindergarten to senior year, Akron Public Schools students love those little paper cartons. But while on-site learning is on hold, Ellet Community Learning Center kitchen manager Julie Shumaker says the milks have taken on new meaning: 8 ounces of much-needed normalcy.

This year will mark Shumaker’s 28th as an Akron Public Schools child nutrition worker. On the Ellet Orangemen Cafeteria Facebook page she runs, Shumaker offers “updates from Lunch Lady Land,” posting news about the district’s summer meal distribution program, photos of puppies and congratulatory notes to Ellet’s 2020 graduates.

“When [students] come through our line and back out through the door, we’re the five minutes of the day that [no one] is harping on them,” says Shumaker. “We get to know the kids more on a personal, friendly basis than just as students.”

Shumaker worries about the students she no longer sees every day. She’s afraid virtual learning won’t fulfill one of students’ most basic needs: food.

“There was already this talk [about being] closed for a long period of time,” explains child nutrition coordinator Laura Kepler. “And schools — not just here in Akron, or Ohio, but across the country — they’re going to have to need to keep feeding meals because too many kids will be going without.”

When Akron announced on March 16 that schools would close for three weeks, APS child nutrition workers rushed to prepare for a meal distribution program designed to adhere to social distancing and public health standards while getting students free and dependable breakfast and lunch every day of the week.

“We really stopped serving in school on Friday, and by Tuesday, we were doing grab-and-go [meals],” Kepler says

Since then, child nutrition workers have continued staffing meal distribution sites through the summer months, serving bagged, nutritious breakfasts and lunches for families to take home — complete with those 8-ounce cartons of chocolate milk.

During an ordinary school year, Kepler says child nutrition workers serve 27,000 meals per day. Now, they’re serving around 6,000 per day. “It seems lower,” explains Kepler, “but that’s almost three times as much as we [normally] do in the summer.”

Kepler says the district has distributed nearly 800,000 meals via 37 meal distribution sites at neighborhood schools across the city since schools closed. Even at distribution sites located in neighborhoods where families don’t typically face high rates of food insecurity, Kepler says the district has seen active participation in the program. certain areas that we thought would get high participation,” says Kepler, “we would have been completely wrong.”

Shumaker, who’s been working meal distribution sites since March, says she now has a different insight into the families APS serves. Instead of working exclusively with students, Shumaker says child nutrition workers are now interacting with parents, grandparents and caregivers at meal distribution sites. “We’ve come to know people,” she says. “And they are just so grateful for the service we’re providing.”

Sometimes, the gratitude Shumaker receives from families is overwhelming. “It’s kind of weird, because they’re thanking us, but this isn’t coming out of my pocket.”

“I’m not doing anything extraordinary,” Shumaker says. “I’m just doing my job.”

Every APS student can eat for free at school. What about remotely?

On July 27, the Akron Public Schools Board of Education announced that students would not be returning to school for on-site learning at the beginning of the 2020-2021 school year. Instead, students will learn from home. But online learning could mean losing access to many of the resources Akron Public Schools provides — including food.

Mark Williamson, director of communications and news for Akron Public Schools, says that just under 97% of students in the district live below 130% of the federal poverty level. For a family of four, that’s a monthly gross income under $3,000 — around $34,000 per year.

Because Akron Public Schools’ poverty rate is so high, the district qualifies for the Community Eligibility Provision, a federally funded program designed to help high-poverty school districts feed students at no cost. Families living in school districts with high poverty rates don’t have to apply to receive school lunches for free or at reduced cost. Instead, districts that qualify are reimbursed by the USDA based on the percentage of families already participating in other food assistance programs, like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

The Community Eligibility Provision reimburses the district for every meal served, which means all APS students can eat breakfast and lunch every day at no cost — eliminating a major barrier to food access for students who may already be struggling to access nutritious foods at home.

But in a city where at least 90% of students and their families live below the federal poverty level, the need for accessible, nutritious foods has only become more necessary during the pandemic. One way to further reduce barriers to accessibility is to create spaces where students and their families feel safe, rather than judged.

When parents and caregivers arrive at a meal distribution site, child nutrition workers hope they’ll encounter an environment free from judgment. Adults aren’t required to show ID, or

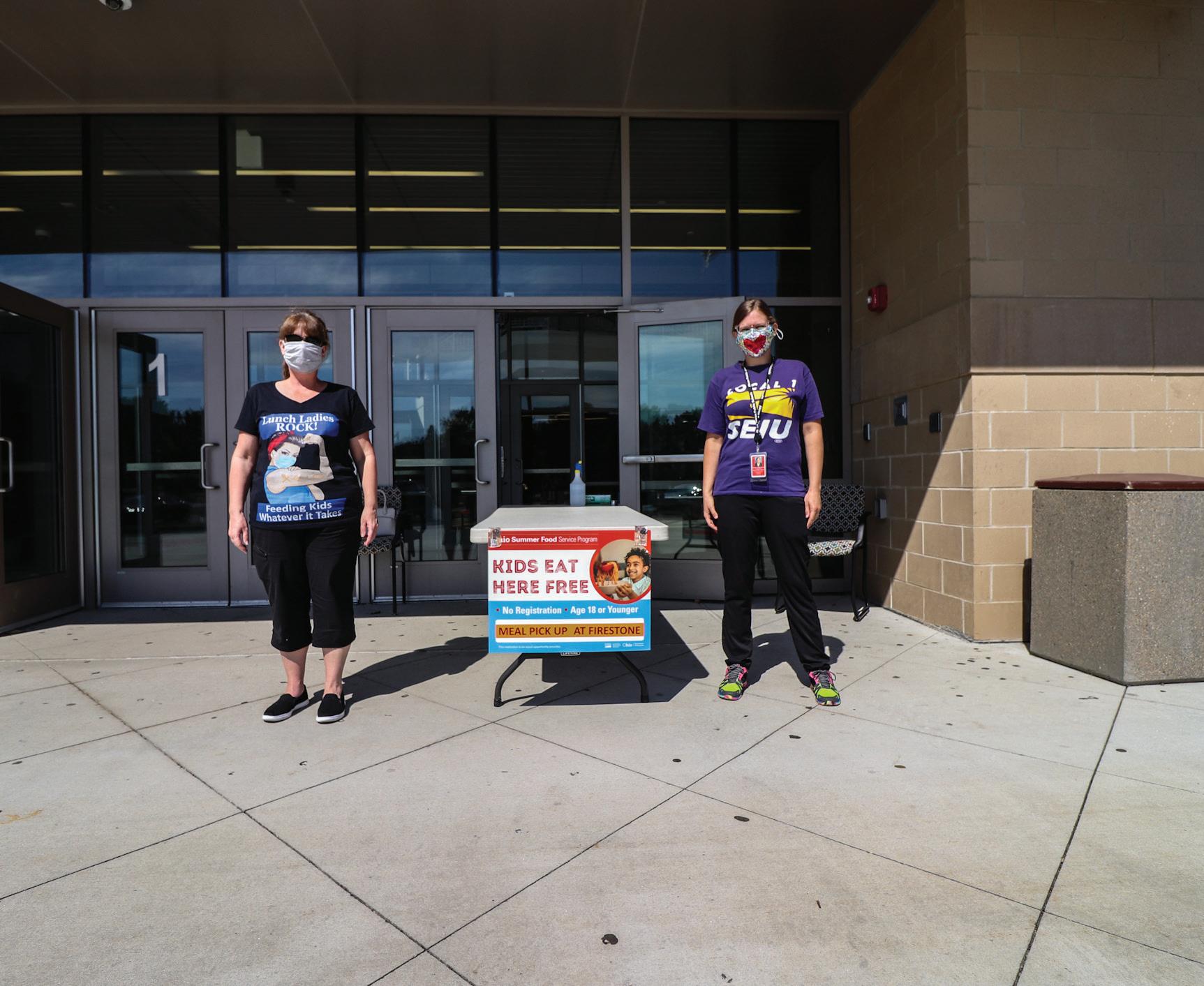

Child nutrition workers Heather Hillenbrand and Diana Stone promote social distancing at Firestone CLC’s meal distribution site.

Hillenbrand prepares meals at one of 37 APS meal distribution sites.

Hillenbrand disinfects a table at Firestone CLC’s meal distribution site.

(Photos: H.L. Comeriato)

provide proof that they have a child in the school system. Any child from ages 1 to 18 is eligible to receive a meal, regardless of which school they attend.

“We’re not asking questions,” says Shumaker. “We’re not here to pass judgment. We just want to make sure these kids are taken care of in some way. Because who knows? Parents may not know when their next check is coming.”

For Heather Hillenbrand, a child nutrition worker at Firestone Community Learning Center, it’s important that APS families utilizing the meal distribution program are treated with dignity.

After years of unfulfilling work in the food service and hospitality industries, Hillenbrand says landing a position with the Child Nutrition Department last year was a welcome change. “I’m really proud to work for child nutrition… I really think we do something awesome. [Students] can come to school and eat and they’re going to be OK. I like being a part of that.”

Child nutrition workers are doing ‘whatever it takes’ — including taking risks themselves

Outside the front doors of Firestone Community Learning Center, Hillenbrand wipes down a collapsable table with disinfectant. The rims of her glasses dip below a pink and purple face covering. Hillenbrand’s co-worker, Diana Stone, wears a T-shirt with an image of a masked Rosie the Riveter. “Lunch Ladies Rock,” reads the text above the image. “Feeding kids. Whatever it takes.”

A car pulls up to the entrance, and Hillenbrand clicks a small counter with her thumb. Over the last few months, she’s gotten to know the families at her distribution site. She recognizes the car, and already knows how many meals the family needs.

Child nutrition workers take great pride in the services they provide for students and their families. But Hillenbrand says she’s worried — not only for students and their families, but for her own health and safety, and the health and safety of her coworkers.

“I love my job. I want to keep working. I want to work on-site.” Hillenbrand pauses.”I don’t want to get sick, and I don’t want to bring something home to my partner that they might not be able to recover from.”

Hillenbrand, who is insured through her partner, says many APS support staff aren’t so lucky.

According to Kepler, around 85% of child nutrition workers live in Akron, and often serve their own communities. But many only work part-time and aren’t eligible to receive benefits through the district.

“At my level, I don’t have health insurance through my job that is exposing me to a pandemic on a daily basis. And that feels bad,” Hillenbrand says. “I assumed a great risk here — particularly when we had no idea what we were supposed to be doing to stay safe — and I don’t feel we were appropriately compensated for the amount of risk that we took.”

In March, when Akron Public Schools first began to address concerns related to COVID-19, there was a lot of uncertainty for child nutrition workers. “I think very early on we realized that we had to follow recommendations for the safety of our employees,” says Kepler. But in the beginning, masks and sanitizers were difficult to come by. “It was scary there for a period of time,” Kepler says. “There was so much uncertainty in the beginning.”

“One of my supervisors [was] purchasing masks on her own on the weekends, trying to get them where she could to make sure we had enough of what we needed. We literally had to go out and buy tape for the floor. Now you can find all the nice signs and footprints and ‘stay apart,’” says Kepler. “But we were trying to, every day, stay abreast of what was necessary to keep our employees safe.”

Still, Hillenbrand says she’s worried for her co-workers who are older, immunocompromised or otherwise at-risk.

“I’m very afraid of actual loss of life,” Hillenbrand adds. “How do we deal with staff death? How do we explain to kids that their teacher is never coming back to school? What do we do?” workers’ safety. “It’s going to be scary to go back. As much as we want to be back and see everybody and see our kids, it’s going to be scary,” Shumaker says. “I mean, there’s concerns all around. We’re concerned for our health. A lot of my crew either falls into a risk category, or they have a family member who does. So we worry about interactions. We worry about how we’re going to pull things together once we do go back.”

In the face of such uncertainty, Shumaker says the gratitude she receives from students and their families has kept her focused and committed. She hopes to provide at least some kind of support and consistency for families who might be struggling.

“If a parent has to make a decision between paying the water bill and buying food for their kid? I just can’t imagine having to decide something like that,” says Shumaker.

She says she wants parents, kids, and caregivers to know that someone cares.

“We’re here for you,” Shumaker says. “We’re here for your kids, and we’re doing the best that we can to keep those little bellies full and keep smiles on kids’ faces. And if a peanut butter and jelly sandwich does that, then we’re doing our job.”

// H.L. Comeriato covers public health at The Devil Strip via Report for America. Reach them at HL@ thedevilstrip.com.

WAKR-TV

Top and left: The Copley Theater and former WAKR-TV studio on Copley Road. Center: The original glass brick set above the front

entrance was once lit by neon. Right: A theater poster light box with the WAKC branding, the call letters the station took on in 1986. (Photos: Charlotte Gintert/ Captured Glimpses)

REPORTING AND WRITING BY CHARLOTTE GINTERT

If you ever noticed what looks like an old movie theater on Copley Road and didn’t know the story behind it, well, I have some fun Akron trivia for you!

The original operation in the Art Deco style building was the Copley Theater, a short-lived venture that opened in 1947. The new theater boasted air conditioning, a marble foyer, and a neon marquee. Neon lights also illuminated the glass brick set above the front entrance. Its grand opening event featured two showings of the Bette Davis and Claude Rains melodrama Deception.

The theater suffered from regular turnover of management and stopped showing fi lms in September 1952. For a time, it was rented to Alpha Rex Emmanuel Humbard, better known as Rex Humbard. He and his family broadcast their Pentacostal programming every Saturday night until 1953.

Humbard is famous locally for founding the Cathedral of Tomorrow. He also constructed Cuyahoga Falls’ highest and most unique landmark, a never-completed rotating tower restaurant that is visible for miles around. After the Humbards’ departure, the theater became home to Akron’s fi rst and only television station, WAKRTV. That’s right, kids, Akron used to have a television station! The station was founded by S. Bernard Berk and started broadcasting from the First National Tower downtown on July 16, 1953. It moved into its offi cial home at the former theater that fall.

WAKR-TV was an ABC affi liate and broadcast to the ultra-high frequency (UHF) Channel 49. Thanks to its ABC affi liation, it secured the rights to about 275 fi lms. It also hosted local news. Its fi rst remote broadcast was of Akron’s Sesquicentennial Parade. From its home at Copley Road, it broadcast the news, children’s programming, talk shows, and cooking shows.

Many of WAKR Radio’s announcers made the switch to TV. For unknown reasons, it was decided that meteorologist Jo Anne Ybarra needed to wear a bathing suit for her segment, while her male colleagues were able to keep the dress code from their radio days.

One of the most popular shows was The Professor Jack Show, a children’s entertainment show that fi lmed in front of a live studio audience. Professor Jack was Jack Bennett, a