8 minute read

Globe Of Granite

Mia Middleton On Creating Cosmologies From Detritus

Mia Middleton in conversation with Elizabeth Fleur Willis

Mia Middleton's structural works explore the dichotomous flux between surface and void, material and mineral. In particular, she focuses on the psychogeography of synthetic and utopic environments by breaking apart and re-purposing the virtual and tangible veneers that typify them. The result is a conflation of the domestic, the organic and the fantastic, where multiple spatialities exist in tandem and coagulations in diverse movements of matter and culture converge.

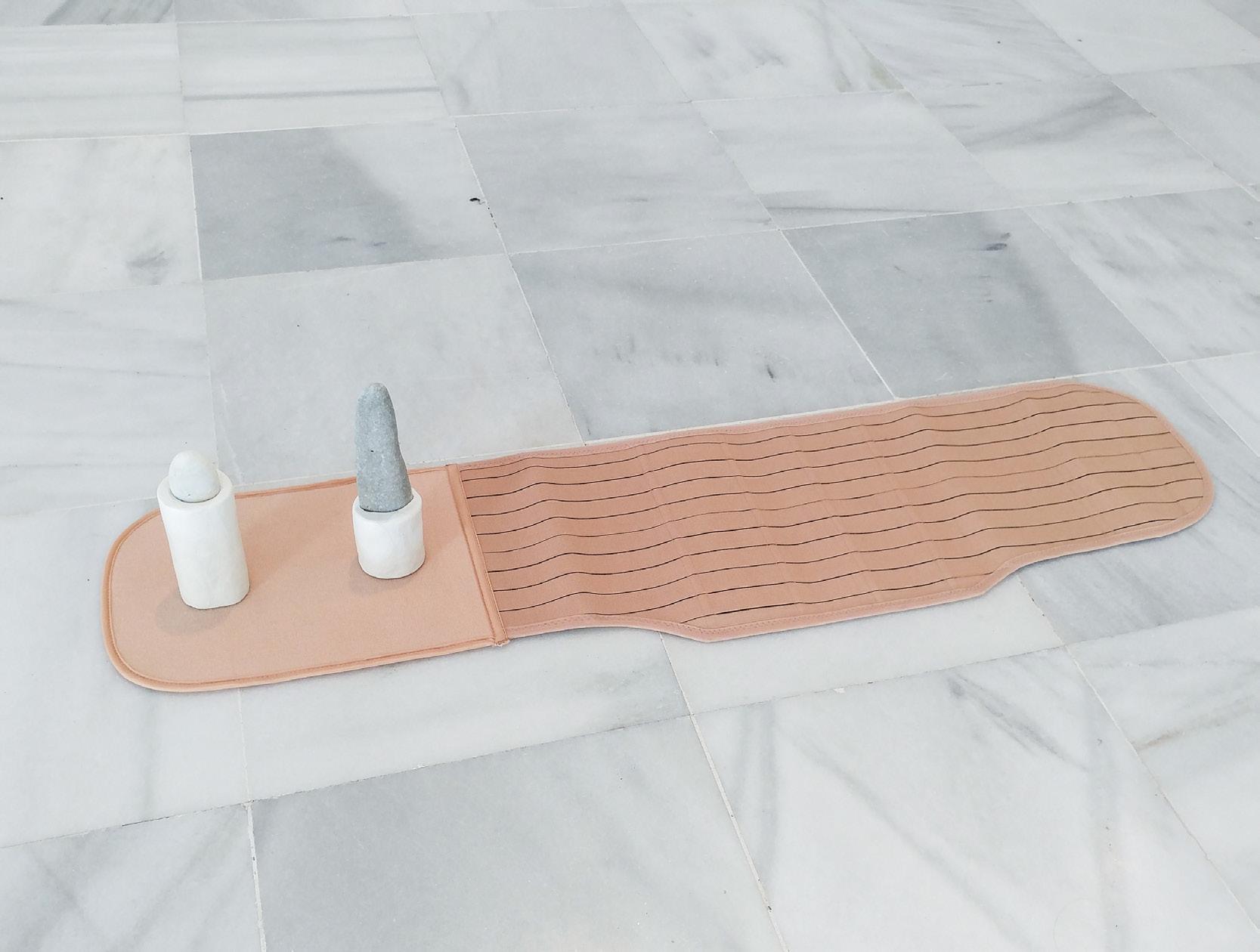

Continuing her transfixion with surfaces and objects that form the physical infrastructure of a place, Globe of Granite is a kind of relational archaeology that takes into account the delicate power balance between consumer culture and the primal landscape that supports it. Mia’s impulse is always to observe and acknowledge these entanglements and create cosmologies from their detritus. For this work, forms collected from public areas were decontextualized and combined with synthetic materials through intimate pairings and manipulations. Rather than situating humanity apart from the earth, the works explore a fused identity that directs awareness to the greater time scales encompassing us in contrast to confining elements of human domesticity.

Elizabeth Fleur Willis: To me, in this body of work, I find there to be a certain tension between ambiguity and direct metaphor within the message that you convey through the choices you make in taking and pairing the objects that you do. Can you tell us what inspires your decision to take an object and create a union with another?

Mia Middleton: There is a tension; the friction is what drives the creation of the work. I’m drawn to these connections and conduits between disparate elements. Juxtaposed and fused objects, textures, references – combined by an action which is often a very clear part of the final work – something wrapped, poked, encased, contained etc. There are lots of reasons why I do this: engaging and playing with matter, to exercise some energy and agency into my everyday environment, to investigate what appears as detritus here at this moment and extrapolate pseudo-narratives, to feel the joy of materials colliding. But I think this impulse is largely inspired by a desire to break down the edges of things – questioning the way we view matter as a collection of independent objects, and illuminating a continuum of the things in the world. I’m simultaneously very drawn to negative space: tracts of space between works, means the viewer doesn’t feel like they have the full scene before them. That spatial emptiness and unknown is also an integral part of the work.

EFW: Can you pinpoint a certain moment or particular project that started you on your journey on incorporating natural elements into your practice?

MM: I can trace it back to my teen years, incorporating organic matter in my creations was always an innate urge whether it was physically present or represented in some way. It really became an integral component of my practice at art school, especially when I was starting to move towards sculpture and installation and away from photography and video which were my original specialisations. This move in itself was partly due to my feelings of pure pleasure regarding physicality and materiality.

EFW: Did your practice evolve or change when you started connecting with organic elements?

MM: It absolutely has. For me it feels primal, so my creative process seems to flow really naturally now that it is fundamentally incorporated in my work. I remember a time when things weren’t so unencumbered but working directly with objects and organic forms really enabled that. I love listening to artists talk about the different ways this ‘hook’ so to speak manifests in their own work - like it might be a certain material or a process that once discovered or invited into the art practice, sort of sets things free. I think artists, especially those that went to art school, often start out thinking art-making is about gamesmanship and outwitting your opponents. It’s a sad thing and there’s undoubtedly some truth to it, but it's beautiful when people realise that for the most part, it’s genuinely beneficial to just follow your bliss through your practice.

EFW: How do you feel when you work with organic elements and within a natural context? Which emotions are evoked?

MM: I feel a sense of interconnectedness and fluidity. Working with natural forms is like working with the body - familiar and delicate and loving. I want to be constantly reminded that all living things are born of the same universal matter, and that humans are obviously not removed from this confluence. Our lives are so human-centric, I mean we’re obsessed with humans and that makes sense! But we’re really part of a vast, incomprehensibly complex thing here and it’s bonkers. I want to get close to that awareness, and I get that when I’m in, or working with natural elements.

EFW: Is the context of the gallery space important to this work and if so, how would it change if you displayed these items in a more natural environment e.g. a forest?

MM: The gallery is a really important part of the work. I’m in love with the gallery in some morbid way. It’s so devoid of life, like a sanitised echo-chamber and it seems so human that we display things in an empty room. Of course, it’s meant to represent a blank slate but it’s definitely not a nonspace. I find it soothing in the same way an ephemeral film might be. And I find it invigorating in the same way minimalism is. The emptiness between works is an important part of my practice. Those unknowns are stark in a gallery context and I try to reveal them further by exhibiting things in a format that vaguely represents a domestic space, but one which is sparse and muted, clearly neither a unified installation nor a series of independent works. One of the reasons the gallery was important to this exhibition is that there are confining elements to this work – things suspended or encased. And many of the materials I’m drawn to are from an urban or domestic context. The artifice of the gallery plays to these themes well. Having said that, I have displayed work in the landscape and I would love to do it again. I did a series of performances in a park and created a sculpture series in a forest and both were very connected to those environments. This particular body of work interacted with the politics of the gallery space intentionally – stark and fragmented, yet peaceful and considered. If I had been making work for display in a forest, I doubt this is what would have manifested.

EFW: What does the word foraging mean to you?

MM: Foraging to me is a state of presence and vitality. Being aware, attentive, curious and as objective as possible. When I find myself foraging, whether in a forest or on a roadside, I feel like I temporarily sidestep the strategic functions of the built environment, or any mental tendencies to focus on constructs outside of the sensory and the momentary, and I dive into an abstract, inventive and resourceful mindset. Innocuous debris and alluring organic matter become portals into vast elemental and cultural systems around us.

EFW.: Did you create your unique process autonomously or were you inspired by help/advice or inspiration from external sources?

MM: There’s an innate autonomy to every artist's process which is a part of what it is to be an artist in the first place. But nothing happens in a vacuum and I know that despite my distinctive urges to work with certain things, my process has absolutely been bolstered by research and guidance. I go through periods when I’m just consuming essays, artist talks and artworks like its literal food. Usually about three months before a show it kicks up a notch and I’ll just be pouring over content that contextualises my creative inclinations or just delights me for whatever reason. I actually find this time incredibly fun and absolutely necessary. I think about times I’ve done this and the artists I’ve discovered who have helped to give me that push in a certain direction. For me, absorbing the uncanny array of creations out there really boosts my sense of creative freedom, and inspires me endlessly. Considering how much of the creative process does happen in a very internal, solitary context, I welcome conversation and contextualisation.

EFW.: Do you have any particular books or websites that have inspired or helped you?

MM: There are so many but these are the ones that have really elevated me at key moments over the years:

“The Complete Cosmicomics” - Italo Calvino;

“A Field Guide to Getting Lost” - Rebecca Solnit;

“The Power of Myth” - Joseph Campbell;

“A Moveable Feast” - Ernest Hemmingway;

“Nausea” - Jean-Paul Satre;

“The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test” - Tom Wolfe;

“Labyrinths” - Jorge Luis-Borges.

I also have a whole lot of the Whitechapel ‘Documents of Contemporary Art’ series books which have been useful. I’m currently obsessed with Manuel De Landa (philosopher) and Peter Wohlleben (forrester/author) and Caitriona O’Reilly (poet). I trawl art sites a lot too.

EFW: What advice would you give yourself when you first started out as an artist. (Have you learned any important lessons through trial and error?)

MM: Experiment endlessly and go where the play/flow is. Explore the work of other artists, learn about the things you love and make sure you notice the little things that capture you. Are you drawn to ambient music? Round things? Start there and explore. Being output-driven means you can’t benefit from the twists and turn of your process. The beauty is in the doing. The context/concept is already there whether you know it or not, and sometimes you’ll flesh that out later, not before. Once some of your primal drives are unearthed, don’t be afraid of big feelings and assertions, or simple actions and abstractions. Live and create for those causes and fascinations you hold dear.

EFW: What advice would you give young artists who want to start to connect with their environments?

MM: Pay attention.

THEEARTISSUE