Winston Churchill’s Efforts to Unify Britain From 1940-1941

Mitra Scholar

Dr. Meyer, Mentor

April 16, 2012

Sarah HowellsOn September 3, 1939, King George VI addressed the people of The British Empire, announcing Britain’s declaration of war on Germany as retaliation for German aggression against Poland. After denouncing Nazi Germany, he called on the British people to mobilize for war. The next day, the newspaper “Daily Sketch” contained an excerpt of the King’s speech, titled with the King’s defining appeal: “Stand calm, firm, and united!”1 As the British people banded together, Prime Minister Winston Churchill emerged as a figurehead of the war effort, both in public and in Parliament.

While Churchill clearly guided the British military to victory on the continent, his leadership on the home front is equally notable. This paper will explore the techniques Churchill used, such as his attention to his public image, his powerful and compelling speeches, and his creation of a coalition government, in addition to civilian displays of support for Churchill’s leadership and the general war effort, in order to demonstrate how he effectively guided the British people through German attacks.

When Churchill assumed the role of Prime Minister, Nazi forces were in the process of conquering wide swaths of territory throughout continental Europe. The British watched in horror as their allies, especially France, fell to Germany. The Western World seemed to be collapsing on itself, and Britain was the only Western European power left to challenge Germany. By September 5, 1940, only a year after the declaration of war, German bombs began falling on London, England’s capital city. Nazi leader Adolf Hitler hoped that class strife and chaos in England caused by the destruction would eventually pave the way for German forces to invade the island.2

During the eight-month attack, known as the Blitz, the British government employed propaganda such as posters, videos, and the British Broadcasting Corporation, a popular news

source, to inform and reassure London civilians. Government-sponsored organizations, namely Home Intelligence and Mass Observation, gave out daily reports monitoring the morale and opinions of Londoners, monitoring the stability of the home front during the heavy bombing.3

Although some historians note the elevated crime rate in London and the objections of political dissenters during the Blitz, the constant high morale and resolve of the British people proved Hitler’s plan ineffective. By May 16, 1941, the Germans no longer had the resources and capabilities to sustain an attack on Britain. Although the war was far from over, the residents of the British Empire could rest assured that their homeland would be safe from Nazi invasion.

The German forces did not account for the surprising resilience of the English people. Britain, prepared for German bombardment, was determined to “Keep Calm and Carry On”4 under the stress of war. Prime Minister Winston Churchill not only organized a strong military effort but also acted as a spokesperson for and organizer of the government. Civilians often looked up to Churchill during the war, as he worked “with a calm assurance and a conviction that this, at last, was the realization of his destiny: to lead his beloved nation in an all-out war for survival and for the universal values it represented.”5 The widespread confidence in Churchill’s governance gave the home front a cause worth fighting for, and the willpower to continue their difficult journey.

Churchill as a Public Figure

As one of the most iconic politicians of the 20th century, Churchill made his bold and overt character a fundamental component of his leadership and his role as the symbol of the British war effort. Because of his quintessentially British appearance and demeanor, Churchill enjoyed a widespread appeal that attracted many civilians to his cause. He was often portrayed in photographs and cartoons circulated by the press, and regularly roamed about England, cigar in

hand, surveying the war effort and the effects of German destruction.6 The English people could trust in “Winnie” to protect their island from the Nazis and to serve as their paternal figure during the frightening insecurity of World War II.7 Their confidence reflected the hope of the Allied civilians that England would come rescue those countries already conquered by Hitler’s regime.

Churchill’s stubborn personality inspired civilians, who admired his unwillingness to let war disrupt the normal way of life in England. Despite the many precautions designed to mitigate the hazards of German military advances, Churchill was determined to keep up his day-to-day routine. By remaining in London for the duration of the war, Churchill demonstrated that he could understand how the civilians fared in the dangerous and anxiety-inducing conditions of the Blitz. Although there were obvious risks associated with having the wartime leader be in the path of Nazi air-raids, Churchill was able to view danger with a grain of reason, thus convincing the English people they could stay in their city homes and attempt to live ordinary lives. He encouraged all of Britain to maintain a calm and functioning home front, undeterred by Nazi threats.

The book Irrepressible Churchill presents a variety of humorous quotes that exemplify Churchill’s unfaltering stubborn character. One instance is particularly illustrative of Churchill’s demeanor; when his wife Clemmie and supporting ministers attempted to reason with him regarding the personal risks he faced, Churchill simply replied: ‘I will have you know that as a child my nurse maid could never prevent me from taking a walk in the park if I wanted to do so. And as a man, Adolf Hitler certainly won’t.”8 His clear unwillingness to back down in the face of danger inspired the British to follow in his path and adopt his stubborn resolve.

Churchill’s physical appearance contributed to his image as the stubborn and slightly eccentric leader of the British people. In addition to his imposing figure and ever-present cigar, his dress exemplified both his role as an official representative of Britain and as a wartime leader.

Churchill began to wear his own form of labor saving uniform, a siren suit, easy to put on or take off, in which he could nap if he wanted during long night-time spells at work. This added hugely to the fast-accumulating Churchill legend: the public called it his “rompers.” In fact, thanks to Clemmie, some of these siren suits were of elaborate and costly materials, velvet and silk as well as wool- for “best” parties in the Number Ten bombproof dining room, and so on.9

These siren suits sum up Churchill’s demeanor: a gentleman at heart, but also conscious of his public persona and of his demanding role as prime minister. He held the respect of the most dignified aristocrats yet also appeared sympathetic to the rationing and wartime lifestyle of the masses. The mental image of Churchill, working away for the country, clad in his odd, yet practical, outfit, appealed to the people and enhanced their trust in him.10

In order to build on this positive mental image of Churchill, photographs were distributed with the intent of revealing the inner workings of his life to the public in a more transparent way. In newspapers, official propaganda, and even in political cartoons; pictures of Churchill circulated widely, especially of him displaying the V for Victory sign, his signature hand gesture. The sign had been brought to England by a man named C.E. Stevens, who thought that the powerful “symbolism” of the gesture and “its Morse code symbols, three dots and a dash, echo[ing] the opening notes of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony” would appeal to discouraged Allied civilians.11 In one typical photograph circulated by the wartime British Ministry of

Information, Churchill strolls down Downing Street. He is clad in a dark suit and matching bowler hat, his right arm lifted in the air, two fingers creating a V.12 Through such a simple gesture, Churchill displayed his own optimism and offered a way for the people to easily mimic him and his unwavering positivity that England was fully capable of defeating Germany.

An Associated Press photograph from 1940 documents Churchill taking shelter from bombs during his visit to the heavily damaged city of Ramsgate.13 Surprisingly, Churchill does not display any anxiety; instead, he smiles cheerfully for the camera. His dark bowler hat momentarily lies on the table next to him, and a protective steel helmet is strapped tightly around his chin.14 Additionally, a variety of photos were taken of Churchill surveying Blitz damages, which were designed to assure the people that the government cared about their situation. A September 1940 photograph entitled “Are we downhearted?” portrays Churchill walking down a damaged city street, surrounded by many grinning young girls and his contingent of calm, assuring officers.15 Two more photographs display London at its worst, when its two centers of powers were destroyed. One, from September 1940, shows Churchill, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth photographed surveying the rubble of Buckingham Palace.16 The other, from May 1941, portrays Churchill surveying the result of Germany’s last stand, the destruction of the House of Commons, as shown in “The stony path we have to tread.”17 In both of these photos, Churchill appears grave and serious, but never desperate or hopeless. Together, these photographs demonstrate that government figureheads were in the same dire situation as the civilians, yet managed to maintain a sense of resiliency and continued on as leaders.

Churchill’s efforts to establish himself as a positive public image were extremely successful with the civilian population, who regarded Churchill as a caring and passionate leader, confident yet realistic. The morning after the bombing of London began, government bureaucrat

Samuel Battersby accompanied Churchill on a scouting expedition, in order to survey what damage had been done. In a personal recollection, Battersby painted a portrait of a teary-eyed Churchill watching as rescuers pulled civilians from the rubble of their homes. When one woman asked him, “When are we going to bomb Berlin, Winnie?” Churchill ardently exclaimed, “You leave that to me!” immediately raising the spirits of the desperate and confused survivors surrounding him. Battersby was wholly impressed by the ability of Churchill, who transformed an atmosphere of despondency into one of hope, and in one single stroke “unleashed the lions in the blood” in only a few words.18

Churchill understood how to reach out to civilians, first dishing out sympathy, then effectively creating an atmosphere of security. In his own recollection of the Blitz, entitled Their Finest Hour, Churchill described an instance in which the people look up to him as a confident paternal figure who would protect from Nazi threats: They crowded round us, cheering and manifesting every sign of lively affection, wanting to touch and stroke my clothes. One would have thought I had brought them some fine substantial benefit which would improve their lot in life. I was completely undermined, and wept. Ismay, who was with me, records that he heard an old woman say: “You see, he really cares. He’s crying.” They were tears not of sorrow but of wonder and admiration….When we got back into the car a harsher mood swept over this haggard crowd. “Give it to ‘em back,” they cried, and “Let them have it too.” I undertook forthwith to see that their wishes were carried out; and this promise was certainly kept.19

Despite all the fame created by his public image and role as prime minister, Churchill remained humble. He devoted himself in the service of his country, and regarded his role not as a

path to glory but as a necessary hardship and great responsibility. Victory was not for himself, but for the nation as a whole.

Churchill as an Orator

In addition to the many methods through which Churchill obtained the respect and reverence of his peers and of ordinary civilians, Churchill was best known for his exceptional oratory skills. Before he assumed the role of Prime Minister in 1940, Churchill demonstrated an ambition to become a great speaker. He wrote an essay entitled “The Scaffolding of Rhetoric,” he worked diligently to diminish his vocal impediments and improve his voice, and studied the speeches of many great British politicians, including those of his father, Lord Randolph.20 As Churchill gradually ascended the political ladder, he became increasingly masterful in his speaking skills. His best works were often improvised as he paced around his office or home, at any hour of the day. Luckily, Churchill could trust in one of his many secretaries to take down his meticulously crafted words.21

Whether delivered in the Commons, on the platform or at the microphone, Churchill’s orations were, as Arthur Balfour once observed, far from being the ‘unpremeditated effusions of a hasty moment.’ For he took enormous care ‘to weigh well and balance every word which he utters’, creating speeches which were formal literary compositions, dictated in full beforehand, lovingly revised and polished.22

When war began in 1939, Churchill’s oratorical skills became essential in his strong leadership of Britain. Whether in Parliament, in public, or transmitted through radio by the BBC, Churchill’s words accessed the majority of British people and motivated them to join the war effort. In 1898, Churchill had said: “I do not care so much for the principles I advocate as for the impression which my words produce and the reputation they give me.”23 Yet by the time he

stepped down in 1945, Churchill had proved that the strong statements that he wished to convey matched the rhetorical power of his speeches.

On September 3, 1939, the day that Britain declared war on Germany, Churchill gave a empowering speech in Parliament that signaled the beginning of his rise in British politics. In his discourse, Churchill stressed the importance of unity within Britain during wartime, foreshadowing his later success as a popular and effective Prime Minister. Congratulating the British people on their strength and character helped Churchill appeal to the patriotic sentiments of those around him. He argued that the population had never been so well prepared to take on such a difficult task and said, “the wholehearted concurrence of scores of millions of men…is the only foundation upon which the trial and tribulation of modern war can be endured and surmounted.”24

Only eight months later, Churchill assumed the role of Prime Minister. At this point, his oratory became more powerful, more frequent, and more available to the general public. He immediately began preparing the public for the impending attacks on their homes by boosting their morale through his inspirational speeches. His first broadcast as Prime Minister, entitled “Blood, Toil, Tears, and Sweat,” introduced many themes that would appear in his oratory over the next year. Churchill emphasized unity in both his coalition and in the general population, the need to protect Britain at all costs, and the effort needed to win the war. He ended his speech on a high note, by saying, “Come then, let us go forward together with our united strength.” 25

As Britain prepared for battle, the emphasis on resolve and solidarity continued to pervade Churchill’s speeches. A few days after his first broadcast, Churchill again addressed the people, this time emphasizing the impending attacks on their homes. His realistic yet determined manner served as a model for all the people tuned in on their radios. The theme of the British

homeland became increasingly important, because it gave the people a cause worth fighting for. Churchill took advantage of British nationalism in his speech: “there will come the battle for our Island – for all that Britain is, and all that Britain means. That will be the struggle.”26 He continued on by encouraging the people to devote all their resolve and effort into the war and asking them to “perish in battle than to look upon the outrage of our nation.” He was requesting total devotion to the country. Before, only military members had been compelled to serve their homeland; now that total war had become a reality, all civilians would have to devote themselves to the cause.

Churchill clearly stated that the defeat of Nazi Germany would be essential to Britain’s survival as a nation. In addition, he attached the war effort to a greater cause: Britain had a responsibility to its empire and to its allies to protect them from enemy aggression. His speech “Wars Are Not Won By Evacuations” extended the island theme that he had introduced before: “We shall go on to the end, we shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be.”27 The glorification of war gave the British people a reason to band together against their common enemy, and put aside their domestic differences for a while. In “Their Finest Hour,” Churchill reiterated his invigorating remarks, inciting everyone to “brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves that, if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, ‘This was their finest hour.’”28 The population understood that it was only a matter of time until the German military turned on British civilians. However, they were encouraged by the elaborate military preparations, by the propaganda of the Ministry of Information, and especially by Churchill’s efforts to emphasize their duty to fight against German attacks.

Before the Blitz even began, the island theme and the knowledge of a greater cause were the main focus of Churchill’s speeches. The advent of the Battle of Britain called Churchill to make a final broadcast on his two main themes. Soon, the civilian’s endurance and patriotism would be tested. On July 14th, 1940, Churchill spoke to the public of the impending danger coming their way, in a realistic yet inspirational tone. Since Britain represented the only Allied power not yet conquered by Germany, Churchill stated that “We are fighting by ourselves alone; but we are not fighting for ourselves alone.”29 By referring to the people as “we,” Churchill grouped the British population into a united team, all working towards the same cause. As Churchill demanded the resolve and effort of British civilians, he also acknowledged the great difficulty of the task at hand. He was asking them to contribute to the war effort, even though the war was still hundreds of miles away and they would receive no direct compensation for their efforts. By titling his broadcast “War of the Unknown Warriors,” Churchill glorified the contributions of each and every British civilian to national mobilization.

As bombs began to rain down on civilian homes, Churchill was obviously distressed by the situation. He confessed to Parliament that “it is very painful to me to see… a small British house or business smashed by the enemy’s fire, and to see that without feeling assured that we are doing our best to spread the burden so that we all stand in together.”30 Despite his many efforts to ease the strain of attack, Churchill worried that he had not done enough. Yet only six days later, Churchill’s mindset had totally changed. Completely assured by the civilian response to the bombs, Churchill was sure that the country would be able to survive the Blitz. The bombings began in London, and the city served as a model of unity and resilience, especially during the first few nerve-wracking days. Even the King and Queen had felt the effects of the bombs, demonstrating the equalizing effect of danger.31 In a broadcast, Churchill commended

the attitude of those under attack: “All the world that is still free marvels at the composure and fortitude with which the citizens of London are facing and surmounting the great ordeal to which the are subjected, the end of which or the severity of which cannot yet be foreseen.”32 The nation had proved itself capable of surviving the Blitz, just by their impressive efforts of the first month. A month after the Blitz began, Churchill announced “We Can Take It!” and was even surprised by the high morale of the people, who acted as if “one had brought some great benefit to them, instead of the blood and tears, the toil and sweat” that Churchill guaranteed.33 Although the attacks spread throughout Britain and lasted many more months, the bombings became a part of everyday life that civilians learned to live with and work around.

Following Churchill’s Example

Earlier sections of this paper have showed how Churchill established his public image, garnering respect for his oratory and his leadership skills. This next section will demonstrate Churchill’s more specific efforts to maintain civilian spirits, and the demonstrations of patriotism that affirm the success of those efforts.

Early into the Blitz, Churchill realized the gravity of the situation: the war had transformed from a distant fight to an everyday toil. While traveling through the streets of London, Churchill caught a first-hand glimpse of the civilian reaction to air-raid sirens, which he recounted in Their Finest Hour. As “night and the enemy were approaching,” he “felt, with a spasm of mental pain, a deep sense of the strain and suffering that was being borne throughout the world’s largest capital city” and worried about the threshold of suffering that civilians were willing to put up with.34 Thus began Churchill’s efforts to instill patriotism and stall civilian dissatisfaction.

With regard to the home front, the government was extremely concerned with sustaining civilian morale, which was especially challenging as bombs rained down on the country. The Ministry of Information put forward propaganda campaigns, including posters, films, pamphlets, and music, all geared towards ensuring civilians that the government cared about them and emphasizing the need to win the war. Other government factions worked to distract civilians from the discomforts of daily life under siege by providing shelters, giving adequate media coverage of the Blitz and of military movements abroad, and by maintaining sirens. Surprisingly, a thorough investigation of The Churchill War Papers and of the Hansard Archives of the British Parliament demonstrates that Churchill was not directly involved in these Ministries. Although he sometime commented on their work, they usually functioned as independent entities. With this in mind, Churchill cannot be regarded as a master of conventional propaganda, like his counterparts Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin proved to be. Instead, Churchill influenced public opinion in other ways: he exhibited concern for the morale of British civilians, and besides being an effective public image and orator, enacted some measures to ensure the continuation of popular support for the war effort.

Soon after the Battle of Britain began, the war turned from a traditional military confrontation into one threatening civilian lives. Churchill suggested to King George VI that he should create a series of medals that honored civilian heroism. Soon, the George Medal and George Cross were created and served as rewards for acts of bravery during the Blitz.35 In an effort to create an atmosphere of patriotism, Churchill mandated that the BBC play the seven national anthems of the Allies each Sunday.36 He understood that the families of Britain had made a tradition of gathering around their “wireless” radios, and used that ritual to communicate Britain’s duty to protect its Allies, which were all already under Nazi control.37 The BBC

became a useful tool for the government to convey messages to civilians, especially considering that “in a Listener Research Survey of February 1941 almost two-thirds of respondents thought BBC news ‘100 per cent reliable and only one in 1,200 thought it ‘completely unreliable.’”38

Through both direct rewards and public broadcasting, Churchill was able to instill patriotic sentiments in the British population.

Civilians responded enthusiastically to the many efforts designed to raise their morale, and demonstrated great resiliency during the Blitz. As bombs began to fall on London, the civilians buckled down for the long haul, yet overall remained positive and cheerful, demonstrating their devotion to the war effort. The Blitz was not an excuse for self-pity, instead it motivated civilians to strengthen the home front, in order to protect their own livelihoods. Churchill later reflected that “many persons seemed envious of London’s distinction, and quite a number came up from the country in order to spend a night or two in town, share the risk, and “see the fun.”39 The attitude of British civilians is quite surprising, considering the desperation of their situation, but reflects Churchill’s success as a role model and their fierce determination to protect their homeland and win the war.

In October, only one month after the bombings began, a resounding “80 per cent of the public felt it was impossible for Germany to win the war solely by air attacks and 89 per cent said they were behind Churchill’s leadership.”40 Rarely can a leader make such a dramatic effect on civilian opinion, especially without the direct use of force or propaganda to sway opinion. Even under attack, as bombs destroyed British landmarks, homes, and ships at sea, the British people were able to assert confidently that they would win the war.

In addition to portraying himself as someone to look up to, Churchill helped create an atmosphere of resolve that emphasized demonstrations of patriotism and encouraged high

civilian morale. By putting a positive spin on the horrifying events of the Blitz, Churchill was able to convince the people that they would eventually outlast the German strikes, adding to a vengeful atmosphere already fueled by the direct attacks on civilian homes. In Churchill’s own words,

These were the times when the English, and particularly the Londoners, who had the place of honour, were seen at their best. Grim and gay, dogged and serviceable, with the confidence of an unconquered people in their bones, they adapted themselves to this strange new life, with all its terrors, with all its jolts and jars.41

Churchill as a Leader of Parliament

When Churchill assumed the role of Prime Minister, he created a coalition government that quickly mobilized for war and exemplified the strong unity of Britain. However, some of his political opponents in Parliament denounced Churchill as a pompous shell of a politician, in an attempt to undermine his ability to charm British civilians. Former Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin thought that Churchill lacked the reason and intellect required of him, stating jokingly that “fairies” had bestowed Churchill with many talents, yet “he was denied judgment and wisdom.”42 He cautions others against taking Churchill’s advice or believing in his abilities as a politician. In Baldwin’s eyes, Churchill was all words, and what he said had little value. However, further research is required to know the true thoughts of Churchill’s Coalition government members, since petty talk such as Baldwin’s could simply be two very tenacious and intellectual Prime Ministers butting heads with one another. This kind of infighting became almost nonexistent from 1939-1945, in order to ensure the intense teamwork needed to fight Nazi Germany.

In contrast to the relative support of Parliament, some radical political groups clearly denounced Churchill. During the war, Churchill had managed to create a coalition government, united around the goal of victory over their fascist Axis opponents. However, British radicals, angered by Churchill’s refusal to compromise with Germany, took a stance against the government. Before the Blitz had even begun, the founder of The British Union of Fascists, Sir Oswald Mosley, was arrested in May 1940 under the Emergency Powers Act. Although the group later condemned his treasonable offenses in their newsletter entitled Action and called for all members to support the national war effort, one must keep in mind that the Fascists were likely trying to avoid the same fate as their leader.43

Other leftists overtly expressed their concerns during the People’s Convention of 1941. Communists and Leftist liberals gathered to plot a takeover of the British government and to begin a movement that “would bring peace by negotiating with the German masses, not with their leaders.”44 Churchill’s realist policy of fighting until Hitler had been completely defeated conflicted with the opinions of these political dissenters. The protesters believed in the class struggles that dominated pre-war English society, when the working class fought against the supremacy of the elite. Churchill was obviously unconcerned by the protests, because he allowed the Convention to take place without any police intervention. The New York Times commented upon this act as a demonstration of “the Government’s inherent strength, just as the impossibility of such a gathering in Germany, Italy or Russia proves the inherent weakness of the dictatorships” and pointed out that the Convention represented but a small minority within Britain.45

Despite the concerns of British political dissenters, most of King George VI’s people maintained full confidence in their government. “77 per cent of people, when asked, rejected the

idea of making overtures of peace with Germany and 82 per cent still thought that ultimately, Britain would win the war.”46 This opinion parallels Churchill’s unwillingness to end the Blitz through negotiations with Germany. Instead, Britain, under Churchill’s command, was ready to fight the Nazis for the long haul.

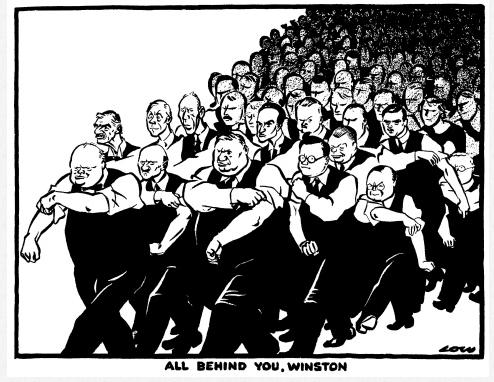

The strength of Churchill’s coalition government contributed greatly to the solidarity of Britain. Churchill maintained a very efficient and effective government, with a cabinet comprised of members of all political parties, which swiftly assembled for war and quickly brought civilians under its protective wings. The clear unity and strength of the coalition government assured the public’s confidence in their leaders and increased patriotism. This is a stark contrast to Hitler’s dictatorship, which often needed to use militant force, intimidation, and oppression in order to garner the support of the German people. On May 19, 1940, before the awful Blitz actually began, The Evening Standard published a political cartoon entitled “All Behind You, Winston” (see figure 1). The cartoon portrays Churchill, along with a contingency of famous English politicians, rolling up their sleeves and marching onwards together. Creation of a coalition government represented a new and exciting experiment in British politics, in which stubborn politicians put aside their grudges in the face of war.

Churchill himself was pleasantly surprised by the quick work of Parliament under his own leadership: “I doubt whether any of the Dictators had as much effective power throughout his whole nation as the British War Cabinet…. It was a proud thought that Parliamentary Democracy, or whatever our British public life can be called, can endure, surmount, and survive all trials.”47 He obtained the respect of his colleagues and of his leader King George VI, by establishing their mutual devotion to the British Constitution and to the democratic role of Parliament, and entrusting his ministers to act responsibly and rightfully. No matter that the

country was under a severe Blitz, because the British leaders were determined to fight for their beliefs and for their country. Churchill led Parliament into a strategic battle, ordinary civilians standing behind them, the whole nation united as one. Unlike Hitler, the quintessence of a totalitarian dictator, Churchill worked diligently to create a strong coalition that everyone, from the Lords of Parliament to the lowliest workers, could stand behind in an effort to defeat Nazi Germany.48

Saving the Western World

Overall, Churchill understood that Britain needed to band together in order to have a fighting chance against Germany. The creation of a coalition government mobilized the country for war, and captured the admiration of civilians. Churchill’s speeches, both over the radio and in Parliament, worked towards maintaining approval of the government and creating a unified home front. Effortlessly, his almost caricature-like personality appealed to the British population, and he rarely concerned himself with official propaganda. As a manipulator of propaganda, he demonstrated no great talent, but as a master of words and as a strong wartime leader, he thrived.

Leading by example created an inspirational and motivated environment that emphasized realism, without resorting to jingoism.

Clearly, there were few objectors to Churchill’s leadership. Although the People’s Convention dictated many serious concerns and was a noteworthy challenge to Parliament, there is little other evidence that opposition to the government was elevated during Churchill’s leadership. Because of his coalition government, Churchill was able to pacify his opposition in government, and because of his admirable character and impressive oratory, he was able to win over the hearts of the civilian population. In addition, the lack of evidence of objectors could be attributed to the need to maintain approval during wartime: government run organizations would

likely frame only positive questions about Churchill, in order to maintain a positive public view of him. In order to be sure of the widespread approval of Churchill, a thorough examination of the records of Mass Observation and Home Intelligence is necessary, yet neither source is accounted for in this paper due to their immense scope and limited access. Churchill conveyed to British civilians that they had an immense responsibility to fulfill: they had to single-handedly win the Battle of Britain, given that the Nazis were swiftly overpowering the Allies. If Churchill had made peace with Hitler in order to end the Blitz, Nazism might have taken over continental Europe.49 In order to convince civilians of the need to fight for their empire’s survival, he employed his natural abilities as a leader and conveyed the duty of Britain to save the Western world from the evils of fascism. The resounding willingness of civilians to follow him into a difficult conflict on their home territory indicated Churchill’s success in unifying the country against Germany. His unfaltering leadership and ability to guide Britain through the Blitz was a key component in preventing Germany from solidifying its new empire, at least until The United States entered the war and Russia joined the Allies. Inspiring resolve within Britain, both in Parliament and in civilians, rendered the Nazis incapable of conquering Britain, causing them to turn on Russia, where the downfall of Hitler began.

In the newspaper Daily Mirror, poet Patience Strong poignantly portrays Churchill’s strong leadership:

We know that we can trust them -— for we know they will not fail.... Although the ship of state may roll and rock upon the sea—They will steer her safely to the ports of Victory. Many are the perils, and the risks that they must take—Many are the dangers of the journey they must make.... May they have the favour of the wind and of the tide—as upon thewaters of the unknown seas they ride.

May their hands be strengthened by the knowledge that we place—reliance in their enterprise. God bless them! We shall face—the future with new confidence in their capacity— to bring us through the greatest tempest in our history.50

Even before the bombing actually began, Britons were prepared for the worst, and they trusted in Churchill’s government to lead them through the war. Churchill served as the strong, unwavering captain of their ship, who led them through Britain’s most challenging trials with staunch resolution. No other politician could have achieved such a decisive victory for his people and for the citizens of all Allied countries.

Notes

1."The King's Message to His Peoples," editorial, Daily Sketch, September 4, 1939.

2. Patricia D. Netzley and Moataz A. Fattah, Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Terrorism (Detroit: Greenhaven Press, 2007), s.v. "Blitz, the," Gale World History in Context (GALEICX3205400078).

3. Robert Mackay, Half the Battle: Civilian Morale in Britain during the Second World War (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2002), 9

4. Mary Dale, letter interview by author, February 2012.

5. Geoffrey Best, "Winston Churchill: Defender of Democracy," BBC History, last modified March 30, 2011, http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/worldwars/wwtwo/ churchill_defender_01.shtml.

6. “Winston Churchill: Defender of Democracy”

7. “Winston Churchill: Defender of Democracy”

8. Kay Halle, Irrepressible Churchill (Cleveland: The World Publishing Company, 1966), 167.

9. Paul Johnson, Churchill (New York: Viking Penguin, 2009), 113.

10. Netzley and Fattah, Blitz, Gale

11. Johnson, Churchill, 116-117

12. "Winston Churchill displaying the V for Victory sign," June 5, 1943, Ministry of Information Second World War Press Agency Print Collection, Imperial War Museum London, http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205022125.

13. "Churchill Dons Helmet," Associated Press, September 6, 1940, New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004666450/.

14."World War II," Churchill and the Great Republic, accessed January 1, 2012, http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/churchill/interactive/_html/2_07_00.html.

15. David Cannadine, ed. Blood, Toil, Tears and Sweat: The Speeches of WInston Churchill (1989; repr., Boston: Penguin Classics, 2002).

16. Cannadine, Blood, Toil, Tears and Sweat

17. Cannadine, Blood, Toil, Tears and Sweat

18. Martin Gilbert, The Churchill War Papers, vol. 2 of Never Surrender (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1995), 788-789

19. Winston Churchill, Their Finest Hour, vol. 2 of The Second World War (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1949), 307-308

20. Cannadine, Introduction to Blood Toil Tears and Sweat. XV-XIX

21. Cannadine, Introduction to Blood Toil Tears and Sweat, XIV

22. Cannadine, Introduction to Blood Toil Tears and Sweat, XX

23. Patrick J. Buchanan, Churchill, Hitler, and the Unnecessary War: How Britain Lost Its Empire and the West Lost the World (New York: Crown Publishers, 2008), 351

24. Winston S. Churchill, Never Give In!: The Best of Winston Churchill's Speeches (New York: Hyperion, 2003), 197

25. Churchill, Never Give In!, 204-206

26. Churchill, Never Give In!, 206-209

27. Churchill, Never Give In!, 218

28. Churchill, Never Give In!, 229

29. Churchill, Never Give In!, 235

30. UK Parliament, "Commons Sittings in the 20th Century," Hansard, last modified 2005, http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/C20.

31. Hansard

32. Churchill, Never Give In!, 252-253

33. Churchill, Never Give In!, 255

34. Churchill, Their Finest Hour, 316-317

35. "George Medal," Ministry of Defence, accessed March 18, 2012, http://www.mod.uk/DefenceInternet/DefenceFor/Veterans/Medals/GeorgeMedal.htm.

36. Johnson, Churchill, 112

37. Mary Dale, letter interview by author, February 2012.

38. McKay, Half the Battle, 146

39. Churchill, Their Finest Hour, 328-329

40. McKay, Half the Battle, 75

41. Churchill, Their Finest Hour, 316

42. Buchanan, Churchill, Hitler, and the Unnecessary War, 357

43. The British Union of Fascists: Newspapers and Secret Files," British Online Archives from Microform Academic Publishers, last modified February 7, 2009, http://www.britishonlinearchives.co.uk/collection.php?cid=9781851171255.

44. James MacDonald, "British Leftists Demand Control," New York Times, January 13, 1941, http://search.proquest.com/docview/105516365?accountid=618.

45. “'The People' In Britain," New York TImes, January 14, 1941, http://search.proquest.com/docview/105522808?accountid=618.

46. Mckay, Half the Battle, 86

47. Churchill, Their Finest Hour, 315

48. Johnson, Churchill, 110-111

49. Buchanan, Churchill, Hitler, and the Unnecessary War, 358

50. Patience Strong, "New Leaders," The Daily Mirror (Manchester, England), May 20, 1940, http://www.ukpressonline.co.uk/ukpressonline/getDocument?fileName=DMir_1940_05_20_007 &fileType=PDF.

51. David Low, "All Behind You, Winston," cartoon, London Evening Standard, May 14, 1940.

Bibliography

Best, Geoffrey. “Winston Churchill: Defender of Democracy.” BBC History. Last modified March 30, 2011. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/worldwars/wwtwo/churchill_defender_01.shtml.

“The British Union of Fascists: Newspapers and Secret Files.” British Online Archives from Microform Academic Publishers. Last modified February 7, 2009. http://www.britishonlinearchives.co.uk/ collection.php?cid=9781851171255.

Buchanan, Patrick J. Churchill, Hitler, and the Unnecessary War: How Britain Lost Its Empire and the West Lost the World. New York: Crown Publishers, 2008.

Cannadine, David, ed. Blood, Toil, Tears and Sweat: The Speeches of Winston Churchill. 1989. Reprint, Boston: Penguin Classics, 2002.

Churchill, Winston. Their Finest Hour. Vol. 2 of The Second World War. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1949.

Churchill, Winston S. Never Give In!: The Best of Winston Churchill’s Speeches. New York: Hyperion, 2003.

“Churchill Dons Helmet.” Associated Press, September 6, 1940. New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/ item/2004666450/.

Daily Sketch. “The King’s Message to His Peoples.” Editorial, September 4, 1939.

Dale, Mary. Letter interview by author, February 2012.

“George Medal.” Ministry of Defence. Accessed March 18, 2012. http://www.mod.uk/DefenceInternet/ DefenceFor/Veterans/Medals/GeorgeMedal.htm.

Gilbert, Martin. The Churchill War Papers. Vol. 2 of Never Surrender. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1995.

Halle, Kay. Irrepressible Churchill. Cleveland: The World Publishing Company, 1966.

Johnson, Paul. Churchill. New York: Viking Penguin, 2009.

MacDonald, James. “British Leftists Demand Control.” New York Times, January 13, 1941. http://search.proquest.com/docview/105516365?accountid=618.

Mackay, Robert. Half the Battle: Civilian Morale in Britain during the Second World War. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2002.

Netzley, Patricia D., and Moataz A. Fattah. Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Terrorism. Detroit: Greenhaven Press, 2007. Gale World History in Context (GALEICX3205400078).

New York Times. “‘The People’ in Britain.” January 14, 1941. http://search.proquest.com/docview/ 105522808?accountid=618.

Strong, Patience. “New Leaders.” The Daily Mirror (Manchester, England), May 20, 1940. http://www.ukpressonline.co.uk/ukpressonline/ getDocument?fileName=DMir_1940_05_20_007&fileType=PDF.

UK Parliament. “Commons Sittings in the 20th Century.” Hansard. Last modified 2005. http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/C20.

“Winston Churchill displaying the V for Victory sign.” June 5, 1943. Ministry of Information Second World War Press Agency Print Collection, Imperial War Museum London. http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205022125.

“World War II.” Churchill and the Great Republic. Accessed January 1, 2012. http://www.loc.gov/ exhibits/churchill/interactive/_html/2_07_00.html.