FIFTEEN PLACES FIFTEEN PLACES

December 2021

December 2021

FM CHAIRS

Olivia G. Oldham ’22

Matteo N. Wong ’22

EDITORS-AT-LARGE

Jane Z. Li ’22

Scott P. Mahon ’22

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Josie F. Abugov ’22

Paul G. Sullivan ’22

Malaika K. Tapper ’22

Rebecca E.J. Cadenhead ’23

Maliya V. Ellis ’23

Saima S. Iqbal ’23

Roey L. Leonardi ’23

Sophia S. Liang ’23

Kevin Lin ’23

Garret W. O’Brien ’23

Harrison R.T. Ward ’23

WRITERS

Isabella C. Cho ’24

FM DESIGN EXECS

Cat D. Hyeon ’22

Max H. Schermer ’24

FM PHOTO EXECS

Sophie S. Kim ’23

Jonathan G. Yuan ’22

PHOTOGRAPHERS

Ben Y. Cammarata ’25, Julian J. Giordano ’25, Joey Huang ’25, Addison Y. Liu ’25, Jane Z. Li ‘22, Santiago A. Saldivar ’24, Zara G. Salem ’24, Aiyana G. White ’23, Meimei Xu ’24

DESIGNERS

Annie Class ’25, Michael Hu ’25, Samanta A. Mendoza-Lagunas ’23, Madison A. Shirazi ’23, Keren Tran ’23

PRESIDENT

Amanda Y. Su ’22

MANAGING EDITOR

James S. Bikales ’22

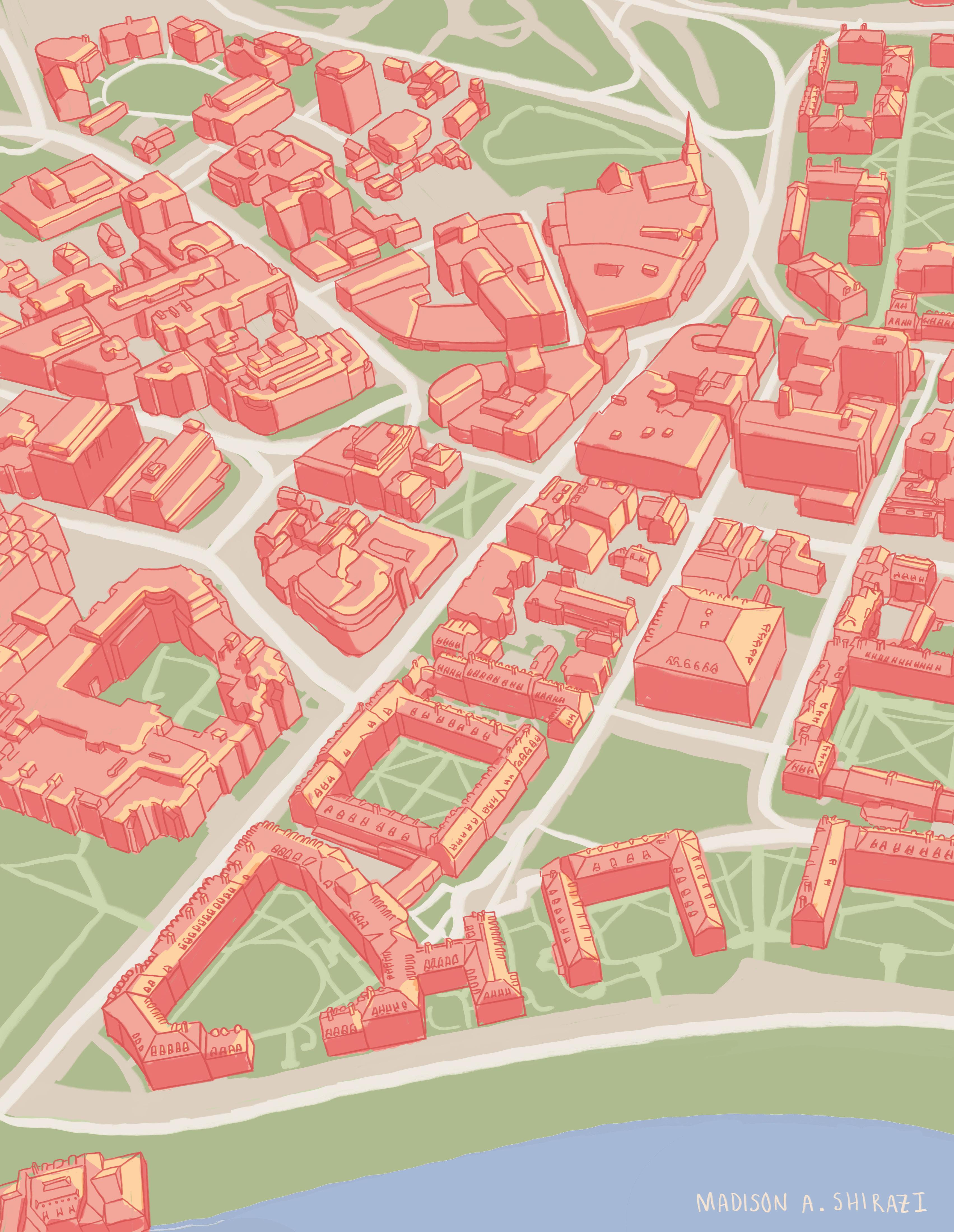

For our final issue, we chose to write about 15 places, a break from this magazine’s history of publishing end-of-year issues about 15 people. In our definition, a place constitutes any physical space in the vicinity of Harvard, from the Weeks Bridge, to Appleton Chapel, to the Yard itself.

After a year cordoned off in our bedrooms, a return to the physical space of campus demands us to look at the physical space of Harvard. What does it sound like? Where does the sunlight come in? What emotions have we attached to its places — melancholy, joy, the flat feeling of exhaustion — and how have those emotions changed in the time since we left?

Of course, people have defined this return. We embraced and broke bread and danced in late August; packed into lecture halls and hunkered down in libraries as the leaves changed; and nearly forgot how much we had missed just sitting in a room, side-by-side, in December. But these interactions happened within a place, or rather, places — points on an ever-shifting map that every student charts anew, a terrain we collectively call “Harvard.” They are spaces we inhabit and traverse, in which we cry and laugh, create and demolish — alone but also, especially after the past year, together.

We started this semester of Fifteen Minutes with two picnics: one for our writers in the lawn by the Cambridge Public Library, and another for our editors in the Quincy House courtyard. Something about kicking off our shoes and feeling the grass under our feet, sweating under the heat of the August sun, and hearing the commotion of Cambridge streets, was electrifying. No matter how close we’d felt over the remote spring, poring over articles late into the night over Zoom, chatting in virtual writers’ meeting, even going on distanced walks — the outright euphoria of being together, the sheer force of dozens of people showing up to hang out in the name of magazine journalism, was a sensation too textured for a computer screen to evoke.

Leading Fifteen Minutes has been one of the deepest joys and greatest honors of our time in college and, frankly, our lives. As editors, it’s a bit strange to be so without words for an experience so full of wonder, so full of love, so rich in its every frustration, challenge, moment of relief. We have a habit of describing FM as “the ground we walk on and the air we breathe,” as though it is not only a single point on our “Harvard” map — 14 Plympton Street, perhaps — but something so constant and abundant it has redrawn the coordinates. Now that we’re walking onto new ground and into new air, FM will change too; under MVE and SSL, it will flourish. Place is not static; it is sought and assembled, made sweet and vibrant by the people who inhabit it. With love,

OGO & MNW

18

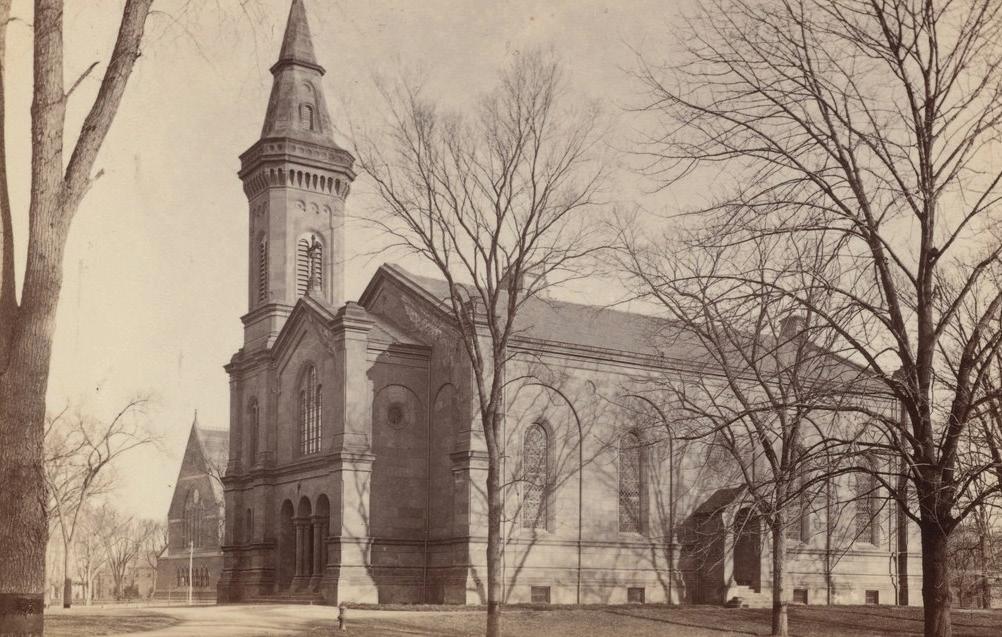

At the front of the Memorial Church sanctuary, partially sequestered by an intricately-carved wooden panel, lies Appleton Chapel. In the morning, pale light streams in through the large, Palladian window; the dawn redwood tree outside casts its shadow on the hardwood floor. Unlike in the church’s main sanctuary, Appleton’s pews face each other, rather than the altar, made for antiphonal singing and immersive listening. Organ pipes lie beneath the wall’s ceramic panels. Iron candelabras stand at the end of each pew; during evening services, they fill the space with a flickering, orange glow.

Memorial Church, as its name suggests, was constructed in 1932 as a memorial to World War I victims. But before Memorial Church there was another church: Appleton Chapel, the stone, ivy-covered chapel that housed the University’s religious services for 73 years. Though beautiful, the small chapel was razed in 1931 to make space for the larger, grander church that presides over the Yard today. Today’s Appleton Chapel is its own memorial, preserving the

name of the Memorial Church’s predecessor from within its brick walls.

Appleton is a beautiful corner of campus — and a piece of history — that few Harvard students ever experience. But it’s one of the places I feel most at home. At 8 a.m., four mornings a week, I make my pilgrimage. Bleary-eyed and yawning, I speed-walk up Bow Street, across Mass Ave, and through the deserted Yard. I join 15 other sleepy students in the choir room under Appleton. Together we are the Choral Fellows, reporting for the equivalent of the early shift: Morning Prayers.

We stretch, warm up, glance over the piece for that day — usually a four-part motet, often in Latin. After a half hour, the conductor has usually managed to transform our early-morning croaking into something like music, and we get ready to head upstairs. I don my floor-length, black-and-red choir robe, and my body relaxes into this forgiving cocoon. As the organ prelude begins, we process in two lines, a la “Madeline” picture books, into the sun-drenched chapel.

I peer out at the congregation — around 25 regulars by my count, mostly older, either faculty members or Cambridge residents. Usually the congregation would join us in the Chapel, but because of the pandemic, they sit in the Sanctuary. I would prefer proximity, but the distance is a small price to pay for being able to sing in-person: I struggled through three semesters of Zoom choir, rife with lag time and void of any sense of community.

And then we sing. The conductor raises his arms, moves slightly to cue the entrance — and harmony fills the chapel. The last note lingers for a second in the air,

them have never heard of.

Morning Prayers, now obscure, were once ubiquitous. They have existed at Harvard since its founding in 1636, and for over 200 years, were mandatory for all students, a standard practice among the Ivy League at the time. They were as much about moral discipline as they were about Protestant worship: strict attendance was taken, and late or absent students were publicly named and even fined.

It’s not surprising that the practice produced much grumbling from students, who launched several petitions to make attendance voluntary. As an 1885 Yale Literary

to “bring the passing and casual under the shadow of the eternal; to make a man feel that amid the confusion of his hurried life, he can lay hold of an unvarying, underlying truth.”

As a Choral Fellow, my attendance at Morning Prayers is compulsory, making my ritual an anachronism. And I’ll admit, not infrequently, the ritual feels like mere routine: I stumble to Appleton, half-asleep, and I’ve dozed through not a few reflections.

But there are also moments when routine gives way to genuine transcendence, even for an agnostic like me, when a reflection will change my perspective, or an anthem will move me to tears. In those moments, I’m reminded of the power of ritual and the importance of a beautiful space, separate from the busy Utilitarianism of campus.

On the first Sunday of this semester, Matthew I. Potts gave his first sermon as newly-selected Pusey Minister of Memorial Church. He stood at the pulpit, robed in white, and addressed the church’s first in-person congregation since March 2020.

before the conductor lowers his hands and we sit for the rest of the 15 minute service.

The order of the service is always the same: a choral anthem, a faculty member’s reflection on an “inspired text,” either religious or secular, and a closing hymn. At 8:45, the Memorial Church bells ring to mark the end of the service. When I rejoin the hustle and bustle of students heading to class, I feel like I’m harboring a secret. I sometimes indulge a small smile: it’s not even 9 a.m. and I’ve already completed a daily ritual most of

magazine editorial, republished in The Crimson, bemoaned: “Running from bed to breakfast, and then to chapel, half awake, with a half learned lesson, is it surprising that a man under such circumstances should lose the religious significance of the duty?”

After a widely-circulated student petition gained traction, the Board of Overseers finally voted to make Prayers voluntary in 1886. The petition also defined what it saw as the true goal of the service, a goal it thought voluntary attendance would better support:

“We’ve resumed our ritual activities,” he said, referencing the church’s prayers, chants, and hymns. “They are beautiful, and they are holy.” His voice cracked before continuing: “And we cherish them. We give thanks for them, these beautiful, holy things.”

As the organ swelled and the sanctuary filled with the first notes of the closing hymn, my own voice cracked and my eyes filled with tears — hidden, luckily, by my mask. There was something sacred about the music and the space, something overwhelmingly beautiful about a nearly 400-yearold ritual resumed.

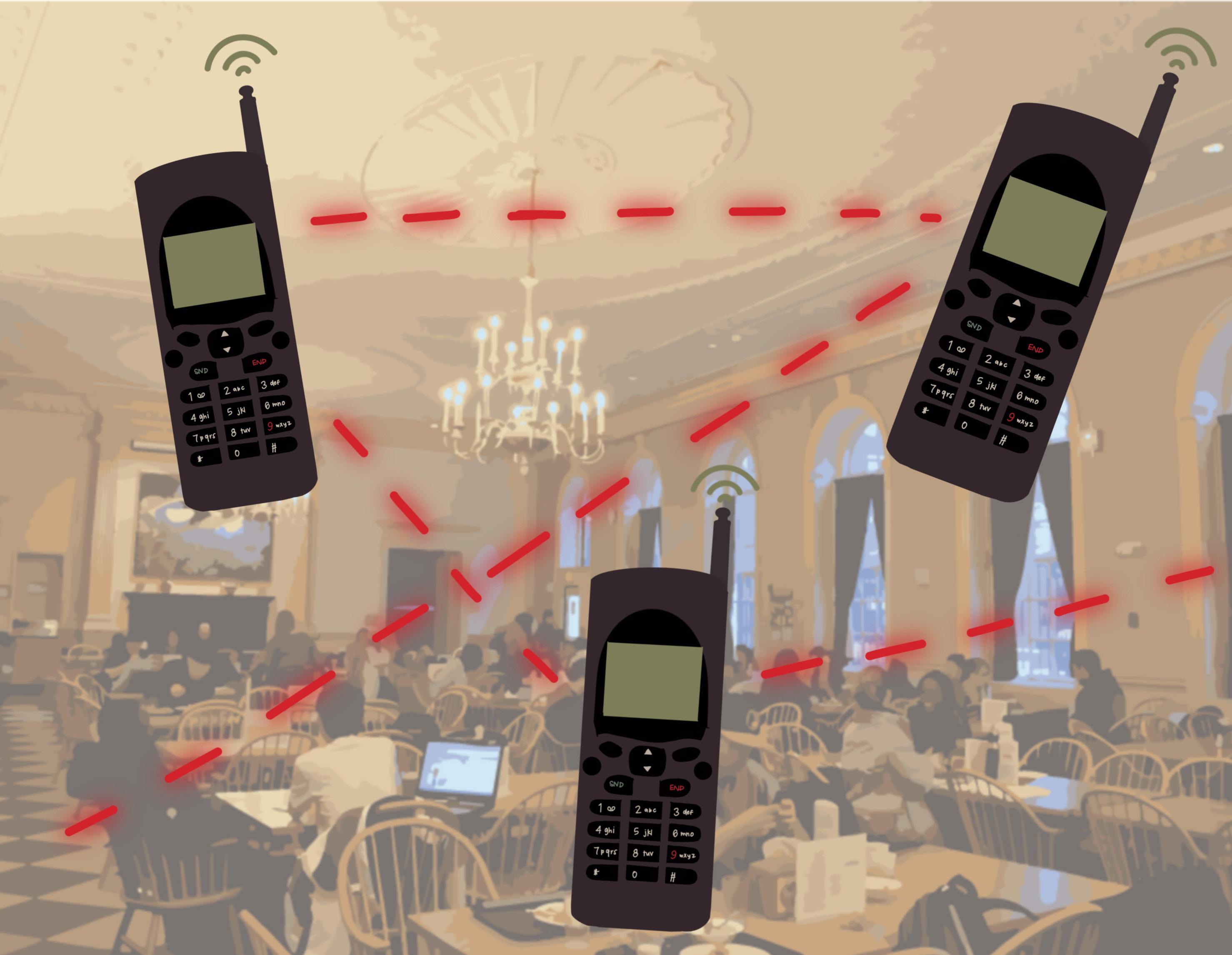

According to researchers at MIT, the Leverett House dining hall is the most economically segregated place at Harvard.

In the Atlas of Inequality, a tool created by the MIT Media Lab, the d-hall has an inequality index of 97.2 percent, and it is visited almost exclusively by low-income people.

Esteban Moro, the principal investigator of the project, created the Atlas in 2016 in order to quantify “micro-segregation” in U.S. cities. He says the government tends to focus on broad residential patterns of inequality, classifying people according to neighborhood-level statistics when conducting censuses and drafting legislation.

“But a lot of the inequality that we experience in our lives is embedded into the things that we do, not where we live,” Moro says. In particular, the places people visit — the cafes, bus stops, movie theaters, and stores they frequent every day — are the primary driver behind the income segregation they experience. Moro and his team are attempting to map this “place inequality,” a measure of how often people of different income levels cross paths, at a finer resolution through the Atlas.

The researchers compiled six months of anonymous location data from 150,000 mobile devices in the Boston area. They assigned each user a “home” census block based on where that person spent the

most time in the evening hours and estimated their income level based on the median income of that census block: low (below $67,000), medium, upper medium, or high (over $114,000). Then, the researchers counted each instance a user stopped for more than five minutes in a particular place as a “visit.” For the 30,000 most-visited places in the area, they determined the share of visitors from each income level and assigned the place an “inequality index.”

Houses are as unequal as Leverett, Currier (86.6 percent), Quincy (79.7 percent), and Eliot (69.2 percent) have relatively high inequality indices as well, all dominated by the low-income category.

Memorial Church skews wealthier, with a 72.8 percent index and predominantly high-income visitors. So do athletics facilities: most Blodgett Pool visitors are from the upper medium-income level, and most Murr Center visitors are high-income.

ting too much stock in the index of any single place, especially on a university campus where most residents are temporary and their true “home” locations are harder to determine. The greatest value of the Atlas, he says, is in its potential to raise awareness of how our daily routines can contribute to largescale patterns of segregation. That is, the Leverett dining hall is not necessarily uniquely flawed, nor even truly the most segregated place on campus — but its provocative red spot on the map does challenge the assumption that the University is a great equalizer for all its students.

“Two people who are living next door can have a very different experience of segregation in their lives,” Moro says.

The most unequal places, with higher inequality indices, were visited primarily by people from a single income level; the most equal were those where people from all four income groups spent roughly the same amount of time.

The resulting Atlas looks like a bird’s eye view of Boston at nighttime, a smattering of color-coded dots overlaid on a gray map of the city. It shows that Harvard Square is one of the most economically diverse places in the Boston area, according to Moro.

Nonetheless, zooming in on the Atlas around Harvard’s campus reveals that even among people who attend the same university, there are disparities in where they choose to eat, shop, and study on a daily basis.

Though none of the other

Some of the most equal places in the area are businesses in the Square, including Felipe’s (11.1 percent), Newbury Comics (10.4 percent), and the recently-closed Starbucks (10.3 percent), but CVS and Darwin’s Ltd. are predominantly high-income.

Places that are similar in function can have drastically different visitor profiles — Widener Library is mostly high-income, while Lamont is mostly low-income. So too can places located in very close proximity — the Law School library is mostly low-income, while the Harvard Law Review is mostly upper-medium. The Business School dining hall is mostly low-income, while the tennis courts just down the street are mostly high.

Moro cautions against put-

The Atlas can also provide immediate feedback on how a change — a new park, a cultural event, or even a pandemic — affects the economic composition of a given place, instead of waiting several years for differences to show up on the census. In the past two years, Moro has seen income segregation increase significantly as people isolate themselves in smaller social bubbles and spend less time venturing to new places. He hopes that the gradual adjustment to post-Covid life will include a re-examination of our habitual behaviors and an investment in new types of physical and social infrastructure.

“I’m optimistic — the data tell me otherwise, but I’m optimistic — that we can mutually build a more diverse society in the future,” Moro says. “We don’t want to come back to what we had before.”

“A lot of the inequality that we experience in our lives is embedded into the things that we do, not where we live.”

- Esteban Moro

The Atlas of Inequality

Jesse P.K. Rankin has lived in Adams House for half of his life. Having spent three of his six years on earth as a resident of the Plympton Street dormitory, Jesse knows things about it that others do not. He knows, for example, that if one wished to ride their small bicycle inside the house, they should head to the tunnels below it, and should one happen to be down there and hope to have a race with their friends, real or imaginary, they are best off starting from the top of a certain ramp and then charging down it, a process which will result in their going “really, really fast.”

Jesse discovered this particular fact last year, when he was living in Adams House with his mother and father, who are tutors there, but most of the other, usual people were living far away.

When it was cold outside, and there were not many other kids to see, Jesse and his mother Alison would go downstairs into the tunnels, not because they wanted to get from one place to another, but to play. It was warm down there, and without many other people around, Jesse would take off his mask

and run as fast as he could, which, let it be known, is “super fast.”

Walking me through the tunnels below our shared home of Adams House on Thursday night, Jesse drags his fingers across murals left year after year by Adams seniors. Soon the paintings may be gone, lost to the renovations. But for now, Jesse knows many of them from memory.

Like me, Jesse enjoys living in Adams House: “It’s kinda good, because there’s some other kids around,” he explains. He is not, however, referring to the fellow progeny of Adams’s deans and tutors. When Jesse says “kids,” he is “thinking of the kids in Adams House, like people in college.” There is no question for Jesse that Adams is a house full of kids; it is only the degree to which each resident is a child that is at stake.

Having spent quite a large share of his time around people who speak in a certain way, Jesse often sounds more like a big kid than a little one.

“Is Adams the best house?” I prompt, eager for a jingoistic generality of the same register.

“Yeah,” he pauses to reflect. “We’re super lucky to have a bunch of the football players.”

es in football.”

Jesse also reports that he has been into Pokémon “for about two

a deal with the humans, and in the daytime, it becomes “People Alley” once again.)

We arrive at a mural outside Apthorp House, where the faculty deans live. Jesse leads me to the etching of interest — Snorlax, I am told — and crouches beside it. The blue fur of the creature is an uncanny match to Jesse’s cobalt tracksuit. I have begun to notice this when suddenly, Jesse remembers a drawing of another Pokémon that he knows, Ditto, and sets off to show me.

It turns out there is a reason for such a maddeningly measured answer: Jesse attends every home game the Harvard football team plays, and he is on both a firstname and Candy Land-playing basis with many of the team members who call Adams home. When asked if he has ever seen a big kid in the house do something really cool, he replies, “maybe, like, make really long touchdown pass-

years now,” though he only got “really into it” at the start of this semester, notes his father, Osiris. Naturally, Jesse knows where one can find the best Pokémon drawings in all of Adams.

As he leads me assuredly across Plympton Street to the artwork in question, we walk by the passageway behind TD Bank and Tatte.

“Rat Alley,” Jesse explains. (But only at night; the rats have struck

Even with all of the things he knows about Adams, Jesse says his favorite place here is the dining hall, and his favorite thing about this house in which he has spent half of his life is the food.

On the flies, Jesse has little by way of comment.

“There were like three in the upper common room,” he reassures me.

“Just three?”

“Yeah.”

“Is Adams the best house?”

“Yeah … we’re super lucky to have a bunch of the football players”Jesse P.K. Rankin, six years old, lives in Adams House. Photo by Zara G. Salem.

In speed chess, whoever controls the clock, controls the game. Many games begin with a flurry of moves and rapid tapping of the seesawed chess clock that counts down the five minutes each player has to checkmate their opponent. The defenses and openings found in every chess book are second nature to the group that gathers outside the Smith Campus Center on any given night. Their boisterous laughs, fraternal camaraderie, and brown paper bags contrast what most think of as high-caliber chess that is played in marble rooms in Europe in the movies. The skill level, however, is not too far off.

Edwin G. Ambrose started playing chess outside the Smith Center 38 years ago, when the Red Line was extended to connect Harvard Square with Porter and Davis Square in 1984. In the ’80s, Ambrose said that chess in the Square “was kind of cliquey,” and it took some time to gain respect and to become a regular. The process of earning one’s place in these cliques is still alive today. As Ambrose puts it, “if you sit down and you’re terrible, no one is going to play with you. If you’re good, then you’re in.”

The Harvard Square chess scene has been home to novices and masters alike. Current International Master Marc Esserman ’05, who currently holds an astounding 2438 rating (putting him among the top 150 players in the U.S.), spent much of his college years refining his skills on these tables. Today, Ambrose says that ranking doesn’t really play into who

Garrett w. O’Brienmatches up with whom; however, players generally know who to target as their competition. Ambrose says that his rating lies around 1900, giving him a Class A ranking and placing him in the 95th percentile of all players nationwide. Despite his impressive credentials, he doesn’t fancy himself as one of the best players who play outside Smith — either a testament to the level of play or Ambrose’s modesty.

The group that plays at the tables is about 40 strong, made up of lawyers, doctors, students, retirees, and even a hustler here and there (I learn this after getting burned a few times myself). The games get going when the sun sets and quickly multiply as players emerge from every direction. When they arrive, there are no ostentatious introductions — simple nods of the head replace overblown greetings. The length of play and size of the group depends on the weather. When it’s nice out, games often continue past midnight.

Ambrose prefers the tables outside of Smith to tournaments for two reasons: “One, you can’t talk and two, it’s not as flashy as what we do out here.” Thirty-eight years later, Ambrose still isn’t bored with the game that he learned from his father when he was five. He comes back almost every night the weather is bearable: “I like the community. I like the foot traffic. I like to play chess, speed chess in particular.”

When prompted to talk about her “obsession” with Cabot Science Library, my friend Karly Y. Hou ’23’24 is quick to clarify that she has in fact never used that word to describe her relationship with the space.

“You use the word ‘obsession,’ not me,” she laughs.

I remind her that when she was asked to provide a meaningful memory of how our friendship came to be for a birthday-themed scavenger hunt, she cited a late, unproductive night in Cabot Science Library, in which “we were both just hysterically laughing.”

I go on to remind her how, throughout freshman year, we would often meet up in Cabot. We would inevitably go on to banter long into the morning before the impending doom of not having finished our assignments set in, forcing us to return to our dorms to actually be productive.

Hou admits to these late Cabot Science Library nights, but with a caveat: “I think it’s very much a freshman year thing.”

Since moving into Eliot House in September, Hou makes clear, she has set foot in Cabot just once.

Assuring me that my assumptions about her attachment to Cabot Science Library weren’t completely unfounded, Hou notes that “in freshman year, Cabot had a lot of star qualities.”

“The most attractive quality about Cabot, the reason I went all the time freshman year is because all our friends were there,” she says. Hou recalls always

arriving there confident she’d find some friends.

“But now if you show up, the chances of seeing our friends there are so low because I think it’s a very freshmen place,” she says.

Hou comments how “the regulars,” as she calls them, have since migrated to House libraries, places like Widener, and their own rooms as they have become upperclassmen. She includes herself among those who have moved on from their days in Cabot Library.

“At the beginning of the year, I was working a lot in the d-hall because friends would walk by and it was like trying to recapture that sense of social studying,” she says. “But then I realized that social studying just isn’t really a thing because if the social is there, there’s no studying happening.”

For the first week of school, the Eliot dining hall was Hou’s makeshift Cabot, until she realized she couldn’t artificially replicate its intrinsic freshman year magic, especially since she wasn’t a freshman anymore.

Hou notes that she has simply changed as a student and as a person, and Cabot no longer serves the role it once did. She reassures me, however, that she’s at peace with that sentiment.

“It’s like a little treasure of the past, you know?” she says. “It’s like your childhood home: you don’t live there anymore, but you think of it, and you think of all the good times you had there.”

Once Margaux R. E. Winter ’21-’22 graduates this semester, they plan to spend several months in two Buddhist monasteries: rising at the crack of dawn, chanting sutras alongside fellow practitioners, and silently meditating for hours. As co-president of the Harvard College Meditation Club, Winter (a former Crimson Magazine editor) already partakes in several meditation groups, but they hope to develop their practice even further. They imagine they will likely meditate “for the rest of [their] life in some capacity.”

I initially viewed meditation as a way to inhabit and analyze your own mind. But for Winter, the practice is not so cerebral or inward-facing. Instead, they say the exercise of sitting and focusing on a singular object allows them to step outside themselves and observe things for what they are. While this shift in perspective is relaxing, Winter says they meditate in the hopes that “seeing clearly” will allow them to “act in a way that serves [themselves] as well as those around [them].”

I get a better sense of what they mean when I visit the space which hosts the Meditation Club’s regular meetings: the Grays Hall Serenity Room. According to Winter, it is the most popular devoted spot for meditation on campus. Located in the basement of the freshman dorm, it is both easily accessible and cozy. A large mandala-patterned rug sits as the center of the room, outlined by several brightly-colored meditation cushions. Warm, orange-tinted light reflects off its exposed brick walls. It is perhaps twice the size of a standard hallway single, but feels much larger. When we meet in the space, Winter offers to guide me through a quick meditation.

We pick out two cushions, close our eyes, and concentrate on our breathing for five minutes. As we do so, the room falls away, aside from the comically loud gurgle of the radiator. I feel at ease until Winter asks me to consider what it feels like to be supported by the ground, by Mother Nature. I don’t know what to think, exactly; they tell me later the questions come from a monk they studied with on a meditation retreat. Afterward, I don’t feel consciously different but I unwittingly mirror Winter’s open posture and repeatedly flex and rotate my achy wrists — the space seems to facilitate this sort of close bodily attention and care.

“In meditation practice, the forms are kind of important, like having your body in a wakeful but restful position,” Winter notes. “Similarly, perhaps

so is having a space that’s made for practice.”

“It has probably changed my life kind of radically now that I think about it,” they reflect.

Winter began meditating as a freshman, largely to de-stress and to reflect on their own thought patterns. The Grays basement was subject to renovation, so they practiced alone in their dorm room. At the time, meditation seemed useful but isolating. They don’t know if they would have stuck with it had they not soon met the “instantly welcoming” community for it on campus.

As a sophomore, Winter attended drop-in sessions with Nina S. Bryce, a tutor in Mather, as well as regular Meditation Club meetings in the Serenity Room. At these gatherings, students would sit in silence for 20 to 25 minutes, and then have space to discuss whatever was on their mind. Winter remembers focusing much more easily in the group setting and being struck by the “deeply spiritual questions” the president of the club posed.

They say that Social Studies lecturer Bo-Mi T. Choi, the faculty advisor to the club, often recounts that in Buddhism, there are three jewels: the dharma, the sangha, and the Buddha. “The Buddha was asked which was the most important of the three, and he was like, ‘Oh, it’s the sangha,’ which means the people you practice with,” Winter explains. “Having people to sit with, the energy literally feels different,” they add.

Members bring a palpable earnestness to their practice and toward each other. In Winter’s eyes, it is what allows the space to do what it does: encourage folks to bring their “full selves” to the group, and help them sit with hard realities, rather than escape from them.

The day the University announced it would send students home last spring, the Meditation Club planned to hold a traditional Tuesday night gathering. After everyone heard the news, they still came to the room at the normal time but stayed much later. In lieu of silent meditation, the members processed the change together aloud, crying and hugging and singing a beloved meditation song.

The gathering felt “very special,” Winter recalls. “To be able to sit in this space with other people who I’m used to being somewhat vulnerable with and have a grounding practice in the midst of everyone not knowing what was happening was very touching.” When I ask them what it was like to return to the room after so long, their reply comes easily: “It kind of felt like a homecoming.”

The 30-minute drive to Mission Hill takes us across the river and down Storrow Drive, before we bear right onto the Fenway exit. Traffic at 3:20 p.m. is often stop-and-go, and we crawl along Hemenway Street before arriving at the Parker Street lot around 3:50. The time in the van distances us from campus, and when I turn around in the driver’s seat I often see a couple pairs of eyes blearily blinking awake.

For the last three years, this is how many of my weekday afternoons have started as part of the Mission Hill Afterschool Program. The program, run by PBHA, aims to ease the burden of after-school education on families by connecting Harvard students with children residing in Mission Hill, a three-quarter square mile neighborhood surrounded by Roxbury, Jamaica Plain, Brookline, and Fenway-Kenmore. I work with 11- and 12-year-olds, providing homework help and leading activities that range from designing a new country, to making slime, to leading field trips to different parts of Boston.

Despite my eagerness to begin serving a new community, I blankly stared at the rows of apartments in the Mission Main development, where our program is located, upon exiting the van on my first day. Lost,

I would bury my head in Google Maps when I picked up and dropped off students. Three years later, however, the street names come easily — Parker Street, Annunciation Road, McGreevey Way.

Still, I can’t shake the feeling that I’m intruding. Noticing the significant gentrification of the neighborhood and my relationship to its causes weighs heavily on my hopes to “do good.”

In 2020, the Globe deemed Boston the country’s “third most ‘intensely gentrified’ city in the US,” specifying that Mission Hill is one neighborhood experiencing gentrification. A 2013 National Community Reinvestment Coalition analysis identified the area just bordering Mission Hill as an area “eligible” for gentrification. Between 2013 and 2017, the median home value rose from $172,377 to $324,100, while the median household income dropped from $23,764 to $16,094 in the same time period.

Not everyone can afford the skyrocketing home prices. Most of our students come from Mission Main and Alice Taylor, affordable housing developments built in the mid-20th century. The Boston Housing Authority described Mission Main as one of its “most troubled and distressed” properties before it underwent renovations in the ’90s. For residents of Alice

Taylor, a collection of townhouses and apartments, rent is calculated at 30 percent of their income, although one can choose to pay a flat rate as well.

One of the more significant contributors to such inequality has been the ever-growing presence of universities and their students, particularly Northeastern and Wentworth. In 2018, Northeastern’s student newspaper, the Huntington News, reported on a meeting where Roxbury residents and housing activists explained how gentrification threatens generational wealth, small businesses, and family displacement. When I drive to program, Northeastern and Wentworth buildings flicker by, and a sign in the parking lot we stop in is emblazoned with the Wentworth logo as well.

Even though I don’t live “up the hill” — an area largely dominated by undergraduates — I still grapple with the space I occupy in Mission Hill as a Harvard student. Just last year, while living in Dorchester, I reflected on how I benefited from a housing crisis that threatened other people’s homes; when I walk through Mission Hill, I wonder if my personal contributions are beneficial or performative.

Yet I still believe that I have been pushed to engage with the community as much as possible. One of

our last in-person events was held in the community center; we set up games in each of our classrooms, inviting students and their families to spend their Saturday evening with us. Pizza for events is ordered from Chacho’s, a local restaurant. If I forget materials for an activity, I’m instructed to go to Fuentes, a local convenience store located a five-minute walk away. And most notably, we support a Junior Counselor program in which students who have aged out of the program can return as paid counselors and receive additional mentoring opportunities.

I haven’t been back to Mission Hill for MHASP since March 2020; we’ve spent the last year adapting our curriculum activities and tutoring strategies to Zoom. But I did return to Mission Hill in the summer, this time entirely as a visitor. I was meeting a friend for lunch, and he suggested a restaurant on Tremont Street, one of the “trendy” places “up the hill” from Mission Main and Alice Taylor. A sign on the door informed me that they were closed for the week.

I breathed a sigh of relief; we left for a restaurant outside of the neighborhood, instead.

The last time I was seriously injured on a bike was (virtual) Housing Day 2020. After I got quadded, I wanted to ride my mountain bike along a local trail to get my mind off the disappointment of landing in Pforzheimer House.

Feeling the familiar contours of the trail underneath me stilled my mind until I turned a corner and saw an unleashed dog quickly running up the trail towards me. I slowed down and drifted to the right side of the trail to give it plenty of space. As I did so, I was briefly aware that I had left the ground. Then, I was acutely aware that I had hit the ground.

I had drifted too far to the right and smashed my right foot into a rock, sending me headfirst over my handlebars. I got off the ground and biked the four miles back home as my right shoe filled with blood.

In my eight years as a cyclist, I have had many minor accidents and even more close calls, most caused by something (like an unleashed dog) and I not being able to occupy the same space at the same time.

When I moved back to Cambridge this summer, I started biking in the city for the first time. Among cars making unannounced right turns, buses drifting into the bike lane, and jaywalkers stepping into the street with no warning, every ride was haunted by the threat of collision.

It took me several weeks to figure out how to safely ride through the rotary near my sum-

mer apartment, and another two weeks to figure out how to cross the portion of Massachusetts Avenue by Johnston Gate where the bike lane suddenly ends on the right side of the road and reappears on the left.

By late June, I had things figured out, but I still didn’t feel at ease. When you are on a mountain bike, you can fool yourself into thinking that it’s just you and the trail, that any danger you face is a consequence of your actions. On a road bike, sharing the streets with hundreds of pedestrians, motorists, and obstacles, you never feel in control — the street is chaos.

Rivers Sheehan ’23, who has been biking in Cambridge since last October, tells me commuting around Harvard Square has heightened her awareness of the “unpredictability of behaviors.” After biking the same routes every day, she says, someone might want to “see everything as predictable, but actually, people are doing things that are so outside the norm, that that in itself is the norm.”

That makes any place in Cambridge where cars, pedestrians and cyclists meet a nightmare to navigate. Take Mt. Auburn Street, for example: you have students “walking back and forth” and cars that are “annoyed at having to wait,” Sheehan says.

Even in ideal conditions — wide bike lanes and protected shoulders — accidents still happen. Sheehan’s was on Mass. Ave., about two months ago, just past the Law School.

She was on the right side of the bike lane, trying to avoid the fast-moving traffic to her left, which pushed her closer to the cars parked to the right of the bike lane. Traveling around 17 miles per hour, a parked car opened its door, and “I hit my brakes as the door hit my face,” Sheehan says.

Many cyclists, to claw back some of control, ride on the sidewalk in the most dangerous areas of the Square. Nicole S. Kendall ’24 tells me that a few weeks ago, a cyclist hit her on the sidewalk by Johnston Gate, one of the most congested intersections in the Square, as she was talking to a friend. The collision caused lacerations and bruising on her hip.

She says she understands why fear would drive bikers to the sidewalk, but doesn’t understand why they can’t just slow down and walk their bike. “If you are not comfortable,” she says, “you can’t just break the law, because you will hurt someone.”

Much of the conflict between cyclists, pedestrians, cars, and buses is avoidable. Dedicated bike paths can reduce collisions between bikers and vehicles; people are unpredictable, which makes sharing space tricky — so don’t make them share space.

These moments of entanglement in the bike lane are scary, an unfortunate addition to many Cambridge residents’ daily commutes, but in many respects, they are also the bike lane’s central feature — defined not by what is meant to be there, but by what is not.

Harvard Yard is chaos. It’s a hubbub of scooters and selfie-sticks. There are the students — speeding to class with such urgency you might think they’re on their way to deactivate a time bomb, or drifting in a cloud of self-doubt, staring down at their shoes. In Harvard Yard, you push past tourists, repeating “excuse me,” “excuse me,” “excuse me,” like some personal mantra. Harvard Yard, most of the time, is merely a route to other places, not so much a place in and of itself.

This, at least, has been my experience of Harvard Yard. I grew up in Cambridge and, as a teenager, the Yard was a shortcut from home to high school. I walked through it quickly, became expert at maneuvering around tour groups and outpacing Harvard students. In college, my relationship to the Yard only changed a little. I woke up after my first night sleeping in my dorm bed — on the first floor of Matthews — to a towheaded blonde family peering through my window at me, half-asleep and twisted in bed sheets. I kept the blinds closed for the rest of the year and joined the herd of Harvard students, noticing, as I walked to class, the newest scuff on my Doc Martens.

Then, in the summer of 2020, a few months after the start of the pandemic, something in the Yard shifted. Students and tourists cleared out of Cambridge and, in their absence, Cambridge locals made the Yard into a sort of commons. Young married couples brought picnic blankets and plump babies who pulled tiny fistfuls of grass out of the earth. Groups of friends constructed circles out of beach chairs and set down packs of beer and pizza boxes, turning the Yard into the site of a dinner party. Impossibly fit people ran up

the steps of Widener two at a time; preteens plopped iPhones against trees and filmed TikTok dances; elderly couples passed through on their afternoon walks, moving slow, slow, slow.

That summer, I also nestled myself within the gates and under the trees of Harvard Yard. I was usually alone. I spent hours writing music reviews that were too long and too personal. I read slowly, resting books on my belly and looking up at the sky and thinking languorously about how Harvard Yard was designed for just this: contemplation. It was modeled after the commons of Oxford and Cambridge, which, in turn, were modeled after monasteries. These spaces, fully enclosed on all sides, were meant to cut off students and monks from the outside world and facilitate reflective thought. When you entered them, you were supposed to feel like you had left behind the breakneck pace and overstimulation of everyday life.

Earlier this semester many people argued that access to the Yard should be restricted to Harvard affiliates only. Reasons were tossed around: health, safety, but, most interesting and perturbing to me, the necessity for quietude and contemplation. But, from what I experienced last year, it seems like the way toward that lies less in who uses the space and more in how the space is used. That summer, when I experienced contemplation in Harvard Yard, Harvard affiliates were nearly absent; instead, it was full of locals who were using the space in intentional, communal, unhurried ways. The Yard was not cut off from the world that summer — the world had just entered it in a different way. Not scooters, but beach chairs.

Aiyana g. White

Aiyana g. White

With its striking modern design rendered in glass and concrete, th Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts stands in sharp contrast to the many traditional, red brick buildings typically associated with Harvard’s campus. Completed in 1963, the Carpenter Center is the only structure in North Ameri-

ca designed by legendary Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier. For architecture buffs, the building alone is a wonder to behold, but behind its stark walls Harvard student artists spend hour upon hour creating masterpieces in their own rights.

“It’s kind of like you’re working in a museum,” says Meghan E. Grady ’23, an Art, Film, and Visual Stud-

ies concentrator who is currently taking two classes in the Carpenter Center. Grady switched into AFVS from Integrated Biology during her sophomore spring. Because of the pandemic, this semester is the first time she’s stepped foot in the Carpenter Center; pre-

Near her workbench, Grady has pinned up her most recent piece, a series of vibrant silkscreen-printed images of crushed soda cans which she says are both “an exploration of color” and “a commentary on consumerism.”

Another factor which contrib-

not get art off her mind.

For Amudo, on a campus where the vast majority of students do take more traditional academic paths, the Carpenter Center offers a “secure place where art is taken very seriously,” and she feels “very supported by being in [the] building.”

She loves its huge windows and the natural light they provide, reminiscing on an early morning spent painting her final project for her first art class at Harvard — a series of black-and-white oil paintings depicting close up shots of her mother’s face — when she watched the sun rise over her canvases from the building’s third floor.

viously, the only Harvard art class she had taken was online, with her bedroom serving as a makeshift studio.

“At home, it was like, I have to pack this all up so I have space to take my chemistry test,” she jokes. Now, she relishes in the ability to leave her projects half-finished and return to find them untouched, waiting for her to pick back up where she left off. Indeed, the Carpenter Center’s studios are strewn with students’ works in progress: clay sculptures rest under tarps, sketches hang taped to the windows, half-mixed paints harden on palettes.

Grady also feels that making art in a shared studio offers more opportunities for collaboration. Working alongside other artists, “there’s a lot of opinions,” she says, contributing to a sense of camaraderie. She says just looking around at the work of her peers is inspiring: Many students hang their finished projects on the building’s blank white walls, giving it the appearance of an impromptu gallery.

utes to Grady’s sense of kinship with her classmates is the sheer amount of time they spend in the Carpenter Center each week — Grady clocks in six hours between her two classes alone, not to mention time spent working outside of class. For Obielumani N. Amudo ’23, an AFVS concentrator who is taking all four of her classes in the Carpenter Center this semester, this figure is tripled to a whopping 18 hours of class time weekly.

Like Grady, Amudo switched into AFVS from a STEM concentration — Statistics. She says since high school she’s assumed she should study a subject typically deemed rigorous. However, over her gap year during the pandemic, she realized that because she is already on the well-structured path toward working in finance, her concentration decision won’t have a huge impact on her post-graduation career. She asked herself, “If I could study anything, then what would I study?” And despite the pressure to opt for a more traditional major, she says she could

At night, however, she says the studio can feel “lonely” and “eerie,” with its darkened windows’ endless reflections. “Like, what’s out there?” she asks, laughing. It’s part of the reason she’s “always trying to bring people here.” Grady also says that she enjoys the space most with company. “It’s cement floors and cement columns. It’s not necessarily the most warm space,” she admits. “The people really do make it.”

Both Grady and Amudo say they often urge their non-AFVS friends to come work in the Carpenter Center with them while they paint, sculpt, or print. They agree that more students ought to take advantage of the building, even just as a space to study or hang out with friends. “If you go here and you have an opportunity to walk around the space, or look at student art, or take a class, or go with a friend who takes a class when they’re begging, you should definitely do it,” Amudo says. “It’s a very different energy in here than other spaces I’ve been at Harvard.”

“It’s cement floors and cement columns. It’s not necessarily the most warm space. The people really do make it.”

- Meghan E. Grady ’23

On the floor above the Kirkland Dining Hall, in a room I never knew existed, Kevin B. Holden ’05 lives in a suite with a view of the House’s main courtyard. He is not the first poet to occupy the room — a plaque on the door recognizes Elizabeth Bishop’s stay in the same apartment in the 1970s. He has resided there for the past seven years, when he returned to the University as a Kirkland House Writer-in-Residence.

I met Holden at a Kirkland junior dinner. When I expressed how naïve I felt at not knowing my House had a Writer-in-Residence program, he assured me that most students are unaware of “these kinds of quirks” within the House system. Even Holden still finds himself discovering “tucked away” spaces and “libraries within libraries” around campus.

As a student, Holden lived in Winthrop House and studied Comparative Literature and Philosophy, but all of his pursuits outside of class revolved around poetry. He wrote poetry, served on the Advocate’s Poetry Board, was the editor-in-chief of the defunct poetry magazine the Gamut, and worked on the Present!, another poetry magazine which he describes as “really experimental and weird.”

After graduation, he got an MPhil at Cambridge, an MFA at the Iowa Writers Workshop, and a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature at Yale. When he returned to Harvard a decade after leaving, as a Writer-in-Residence and a Junior Fellow in the Society of Fellows,

he was struck by both an intimacy with and a nostalgia for with the places he once knew so well.

“It interests me that a place, so specific, can feel very much coextensive with you, but it also was with others,” he says. “This is really obvious, but when you really try to get your mind around it, it’s a little bit uncanny.”

He recalls how strange it was to walk past once-familiar places on campus — Winthrop House, Grays Hall, the Advocate, the Signet. “When I did come back, a fair amount of time had passed that it felt like a different place. But there is nostalgia and there are these phantom memories,” he says. “It sometimes feels like you’re seeing ghosts of your past, not in a bad way but in a nice way.”

Since returning, he’s found that the academic liberty of the residency program and the Society of Fellows has allowed him to explore the interests he naturally gravitates towards. He’s been focusing on honing his stylistic approach to poetry and writing about English-language poetry from the 1980s and ’90s.

“That was very telling to me, that though I love scholarly work, it’s not entirely where my heart is,” he says. “When I had the time and freedom, I was really mostly just working on poetry.”

Holden’s new book of poetry will be published next winter by NightBoat Books. In the meantime, he’s writing more poetry, as well as a few pieces that

sit “in between genres” of creative nonfiction and scholarly articles. The topics of these essays are wide-ranging: the “asymmetry and emergence” of Leslie Scalapino’s poetry, aspen groves, the aesthetic theory of Theodor Adorno, and the geometry of crystals.

Though he’s focusing on writing, he also does translations — he just finished translating a book of French poetry set to come out in the fall of 2022 — and produces texts in queer theory and philosophy. Whether scholarly or purely

so quickly. And the Houses felt like you were in ‘The Shining’ or

creative, much of his work contends with the nature of poetic language. His dissertation, for instance, interrogated how the strangeness of poetry relates to the non-human: “the organic, the mineral world, and the angelic.”

When Covid hit last year, Holden stayed on campus, watching it empty of students. “It really felt like all the air had been sucked out of the room,” he recalls. “Like a vacuum, it just went so quiet

something — just emptiness.”

Like many during this time, he cultivated a habit of long after-

seven years in Kirkland, he’s advised students in the humanities, hosted literature tables within the house, and continues to serve as a BGLTQ tutor. He’s witnessed traditions both come and go — he remembers when an acquaintance started Haunted Hicks, the haunted house that has evolved into an annual event; and sitting by the fireplace with his freshman year boyfriend, back when students could use the fireplaces in their rooms.

Every year, Holden watches

noon walks. He’d amble along the river in early spring, trek all the way to MIT, and get lost in Kendall Square. Sometimes, Cambridge was so vacant that he’d walk down Memorial Drive in the middle of the road.

After the desolation of last year, Holden has grown accustomed to the coming and going of students since returning to Harvard. “It’s just the rhythm of the year,” he says. During his

students discover and rediscover quirks and hidden spaces within Kirkland House and throughout the school, and finds himself struck by the fluidity of institutional memory.

“Maybe a good metaphor here is a palimpsest, right?” he says.

“There are these layers, and you have their echoes — their echoes of the past.”

“Maybe a good metaphor here is a palimpsest.”

For my first two years at Harvard, the John W. Weeks Memorial Bridge, which sits right outside my Leverett dorm, was nothing more than a means of crossing the Charles River.

But during our final week in Cambridge in the spring of 2020, in the limbo after we learned we’d be leaving campus, I spent at least an hour each day on the Weeks Bridge. It felt like a safe space during such uncertain times — no matter what the future held, I’d still be able to sit on the ledge and watch the sunset.

While preparing to write this piece, I brought a friend, two breakfast sandwiches from Black Sheep Bagels, and a couple of blankets to the Weeks Bridge on a November afternoon. Our only goal was to watch.

It was 70 degrees out, an outlier for that week and the last day of nice weather of the season — it almost felt like a sign.

The bridge was crowded, with constant foot and bike traffic in both directions. A friend walking back from the SEC waved to me. Two shirtless men parked their bikes and started a dance battle, grooving to ’90s pop music.

A family of four attempted to take a selfie, and I offered to take the photo for them, making sure they switched sides to avoid glare. A biker rode by, pulling her dog behind her on a trailer clearly intended for kids. Another man talked on the phone about the party he was hosting the following weekend.

The bridge serves a multitude of functions — it just depends on who you ask.

When talking with some fellow Leverett students, I realized they, too, had done their fair share of observing everyday life on the bridge.

As a part of an assignment for her creative writing class, Lucy Liu ’22 took interest in the plant life on the riverbank next to the bridge. “I actually took a nature walk from Weeks to Anderson with [Leverett] Faculty Dean Brian [D. Farrell], and we tried to ID the plants we saw,” she says. “It was really cool because when you look at the riverbank plants from a distance it seems like this disorderly mess of greenery, but when you look closer there’s enormous beauty and diversity in the plants.”

Similarly, Sarah M. Lightbody ’22 finds a unique solace in the bridge. “I really try to see as many sunsets as possible — I go to the exact halfway mark of the bridge and watch, most of the time solo, but sometimes with friends,” she says. The bridge is special “because it’s somewhere exact that I can return to and watch the days and seasons change while still feeling grounded.”

And for others, the bridge has been a part of a centuries-long Harvard tradition — jumping off the bridge into the Charles River is a bucket-list item that officially stamps their experience at the College.

While it might seem like just another bridge to some passersby, the Weeks Bridge is witness to the many comings and goings of campus. After returning to campus after more than 15 months away, I still go to the bridge on a weekly basis — just to sit, turn on my music, and watch.

Scott p. Mahon

Scott p. Mahon

The apartment I lived in last spring is on the first floor of an old tenement house, three stories tall and constructed from red brick, in North Cambridge. I moved in on a frigid day last March. One of my roommates met me outside the building; I noted the barren front yard, dotted with little American flags, as she led me in. It was remarkably cavelike. Light from its windows was muted by the building next to us, casting the interior of the apartment in perpetual twilight. One of the first things I did in North Cambridge was buy grow lights for my plants so they would survive. We had paid three months’ rent, and so we would remain there through May.

In the apartment, time didn’t exist. On weekdays I worked 9 to 5 at a virtual internship, a period of each day spent mostly in bed or at the kitchen table, staring at my computer screen. By the time I emerged to do things of my own volition, daylight had mostly disappeared. Monday through Friday stretched into one long night. Days only felt real on the weekends.

The building itself began to take on the qualities of a parallel reality. Our landlord, who sometimes stopped by to make lewd comments to one of my roommates, was a balding Irish-American with a thick Boston accent. He usually looked at me with an expression of vague distaste; he never addressed me the entire time I lived there, for which I could have been offended but was actually relieved.

He would often have loud conversations with various workmen about the Kennedy family, who he seemed to feel he knew personally, outside our windows. In April, he told us that he’d be leaving for a week to see their yacht in Florida. I kept finding laminated photographs of the Kennedys in the entryway and in the laundry room, carefully propped up against a vase or a bottle of detergent, only one or two at a time, occasionally switched out, well worn and printed in the same way that one would print photos

of one’s own family.

For weeks, especially when the pandemic seemed dire, I would migrate between the building’s laundry room, our kitchen, my bedroom, and the building’s back porch as if I would never need to go anywhere else. The neighbors kept a colony of bees, which I could see through wooden slats in the back fence. I would often go out to the porch under the auspices of wanting a quiet place to read, but all I would really do was watch the bees, sometimes for hours. I admired their purpose and coveted their tiny diaphanous wings. The key to life, it seemed, lay in being part of a hive.

There was a point, while living in that apartment, where I felt like I was nearing a complete dissolution of self. I was sitting on the ground by the coffee table, fingers pressed firmly into the knots of our beige rug, crying. My roommates and I had been making necklaces for each other; I turned my face to the table, intent on arranging loose beads into increasingly complex patterns so that they wouldn’t see my tears. Maybe I shouldn’t have worried. They later told me that I’d actually been laughing. This might go without saying, but we were all very high. I was bothered by the incident anyway, convinced of its metaphorical qualities. I felt like the apartment was drowning me.

Eventually, I began to refuse to spend any time inside the building at all. By mid-May, when I finished my internship, New England had finally thawed and its trees burst into flowers, which they later shed in favor of deep green leaves. Everything seemed to turn green overnight; I would walk outside and feel blanketed by it. I spent most of my time in those last few weeks outside, wandering around Davis Square or on our back porch. I was looking, I guess, for everything that the space of the apartment seemed to negate. Eventually, I moved back home. During the car ride from Boston to Westchester, I told my mom that I’d never live in a first-floor apartment again.

Isabella b. Cho

Isabella b. Cho

Iam sitting in the dining hall of Eliot House just past 1 a.m. For company, a halffilled cup of soggy Frosted Flakes. Peers at the tables around me grumble about multivariable calculus and Lockean ethics; occasionally, the hall’s mahogany door opens and a student stumbles in looking dazed, shaking droplets from their CVS umbrella.

My post-midnight surroundings are neither miserable nor exciting. From a college student’s perspective, they’re just exceedingly normal.

Yet it’s this very normalcy that over the pandemic took on such a rarefied air. Just months ago, I wrote a letter detailing the surreal condition of being a student at a place I had not yet stepped foot in. Now a sophomore living on campus, I have already begun approaching the ordinary in a characteristically pre-pandemic way. So here I am, writing to remember:

Graphic by Annie Class.As a freshman quarantining in the suburbs of Chicago, I resolved to never forget that the normal was sacred. Yet here I am, forgetting.

Perhaps part of it is a function of the quick pace at which life moves on your campus. There’s always another meeting to attend, another book to read, another position to chase. We are, both as a University and a society, so fixated on the promise of newness: new visions and strategies, new systems and ideas.

Here, we lionize the initiative to get ahead. But as I’ve sat in your libraries reading Morrison and Fanon, as I’ve written articles and run to meetings, it’s dawned on me that if I become too occupied with my own work, I’ll miss out on chances to look beyond myself — to observe and learn from all the lives being lived alongside my own.

Looking back, the most enriching experiences I’ve had over the past months have been the ones where I don’t insist on placing myself at the center, but rather bear witness to the talents of those around me: watching my classmate’s football game, reading a friend’s screenplay, hearing about a peer’s post-grad dream.

I’ve realized the most vital lessons these four years with you can provide are not those we have yet to learn, but rather those we can’t afford to forget: spontaneous moments of wonder, the thrill of growth, the redemptive magic of time spent with good people. Things we have understood, at least vaguely, our whole lives.

Still, despite the sense of belonging I’ve been fortunate enough to feel on your campus, the past months haven’t been without qualms.

The future can be disquieting. When I’m walking home to the Quad after a long day, I find my thoughts wandering to where I’ll be five, 10, 20 years down the line. I want a stolen glance at whatever version of myself waits on the

ston when I miss Korean food, and savoring overpriced coffee at Blue Bottle, and reading in Widener as the sky goes dark. To falling in and out of love — with people and ideas, stories and places — and being alright with that.

The rain has stopped. It’s nearing 3 a.m., and nearly everyone has gone. In the far corner of the dining hall, a student scribbles furiously in a book, brandishing one colored pen after the other. I work methodically, buoyed in some vague way by the presence of that stranger. Through the gossamer mesh of the window, I can make out the lawn and the dark trees. Beyond that, the gate and the river. Your ordinary fixtures that were for me, just months ago, nothing short of a miracle.

other end. A glimpsed affirmation that, at least in some capacity, things will work out.

And yet, I suppose there is a power that comes with lacking answers. With lingering in the discomfort of uncertainty before reaching for closure — before telling those around me who I am, and what kind of person I aspire to be.

So here’s to the next two-and-ahalf years with you. Here’s to victories and losses, celebrations and heartbreaks. Here’s to good decisions, and bad ones, too. To more long walks along the Charles, and post-midnight DoorDash, and crashing at my twin’s dorm when it’s 2 a.m. and the Quad seems far away. Here’s to marching to All-

Like most nights when I get caught up in my writing, tomorrow is already here. In a few hours, the dining hall will open for breakfast. Bleary-eyed students will sip orange juice or coffee over p-sets and half-baked essays. The cafes will fill up, and cars will clog the streets. Campus will breathe and move.

You wait for no one so we rush out to meet you, tired and eager, brimming with our bright ideas and private dreams. Like any other day, I’ll go out to meet you, too. As I pass Smith and the Yard, walk through Barker and look over the bridge, I’ll realize all over again that if there’s anything you’ve taught me, it’s that I am just beginning. I hope I always will be.

There’s a power that comes with lacking answers.