THE HARVARD CRIMSON

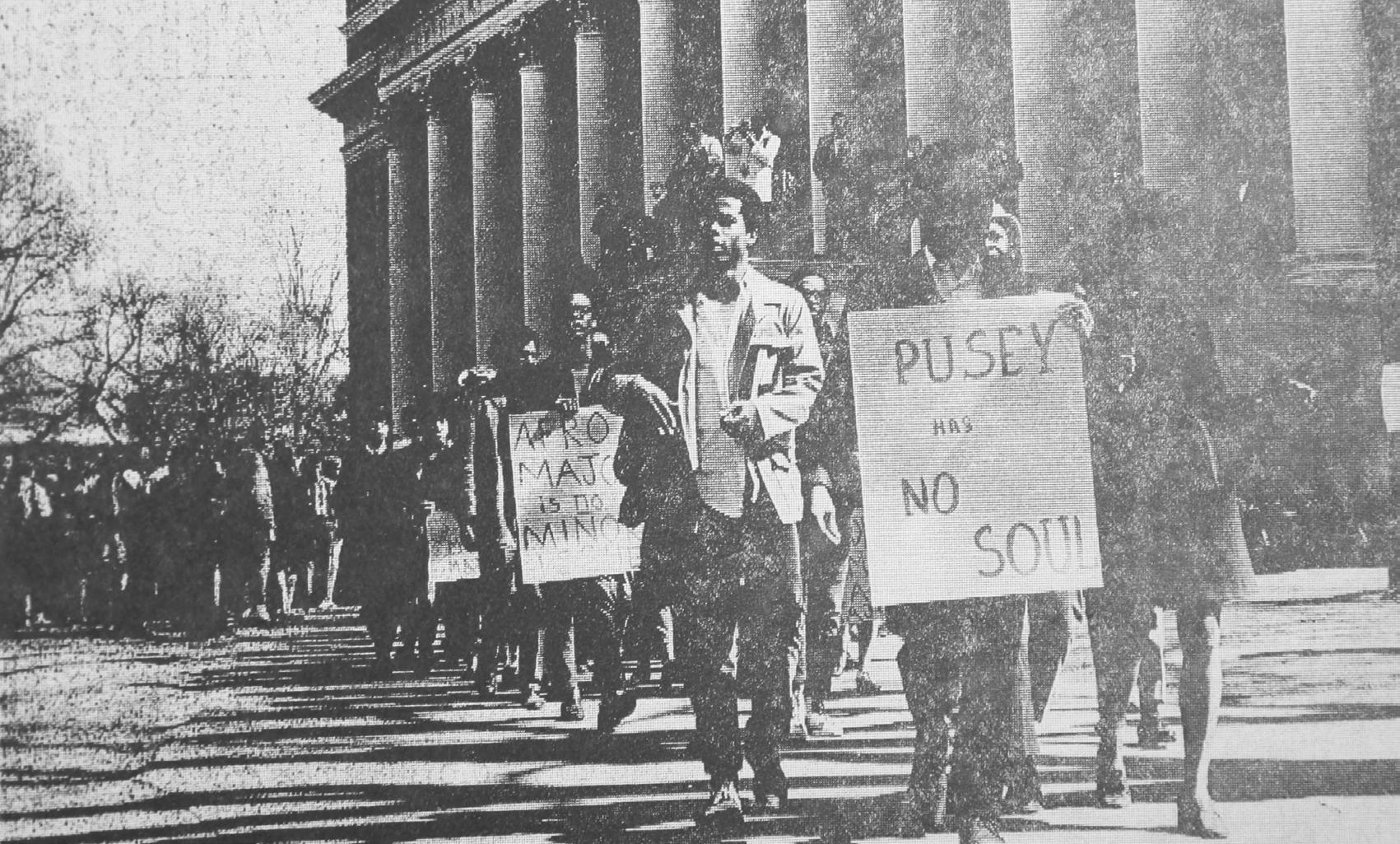

NATIONAL SCANDAL. Students

hearings. Not only did the scandal

In the fall of 1973, Harvard’s treasurer decided the University should control its own purse strings.

The University’s endowment totaled $1.4 billion — a small fraction of its nearly $51 billion today, but still the largest university endowment in the world — and for over two decades was managed by the Boston-based State Street Research and Management Company.

Harvard’s treasurer George Putnam Jr. ’49, though, felt that Harvard should have more authority over its own finances, and on Oct. 23, 1973 he announced that the University planned to establish its own management company to handle its endowment. Shortly thereafter, the Harvard Corporation approved the proposal, gradually shifting the University’s holdings to the newly founded Harvard Management Company — which stewarded an explosion of growth in the University’s endowment in the following decades.

At the same time, however, the University had been grappling for years with fierce protests over its holdings in Gulf Oil, which was deeply involved in the Portuguese occupation of Angola. As of February 1972, Harvard had 680,000 shares of Gulf Oil stock worth $20 million.

While the protests did not directly lead to the founding of HMC, the two events represent a moment of heightened scrutiny in University history regarding Harvard’s endowment — and embody the long history of Harvard’s financial holdings as a site of student protest.

‘An Onward Struggle of Humanity’

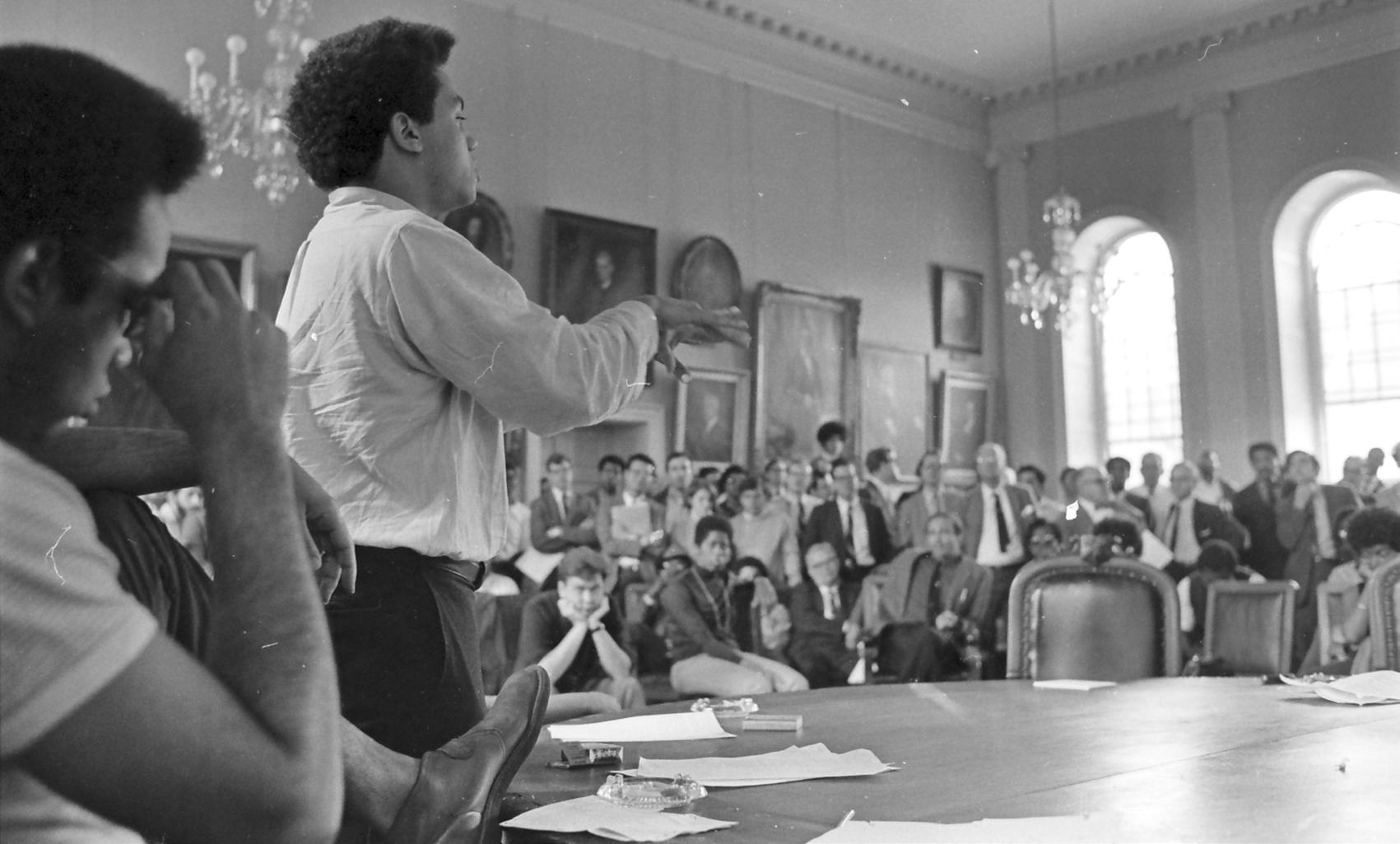

On April 20, 1972, 34 student protesters occupied Massachusetts Hall at dawn to protest Harvard’s holdings in Gulf Oil. They would stay there for nearly a week.

The occupation — staged by members of the Pan-African Liberation Committee — was the peak of the PALC-led movement that demanded Harvard divest from its investment in Gulf Oil. They would be joined at the start by up to 100 supporters, who

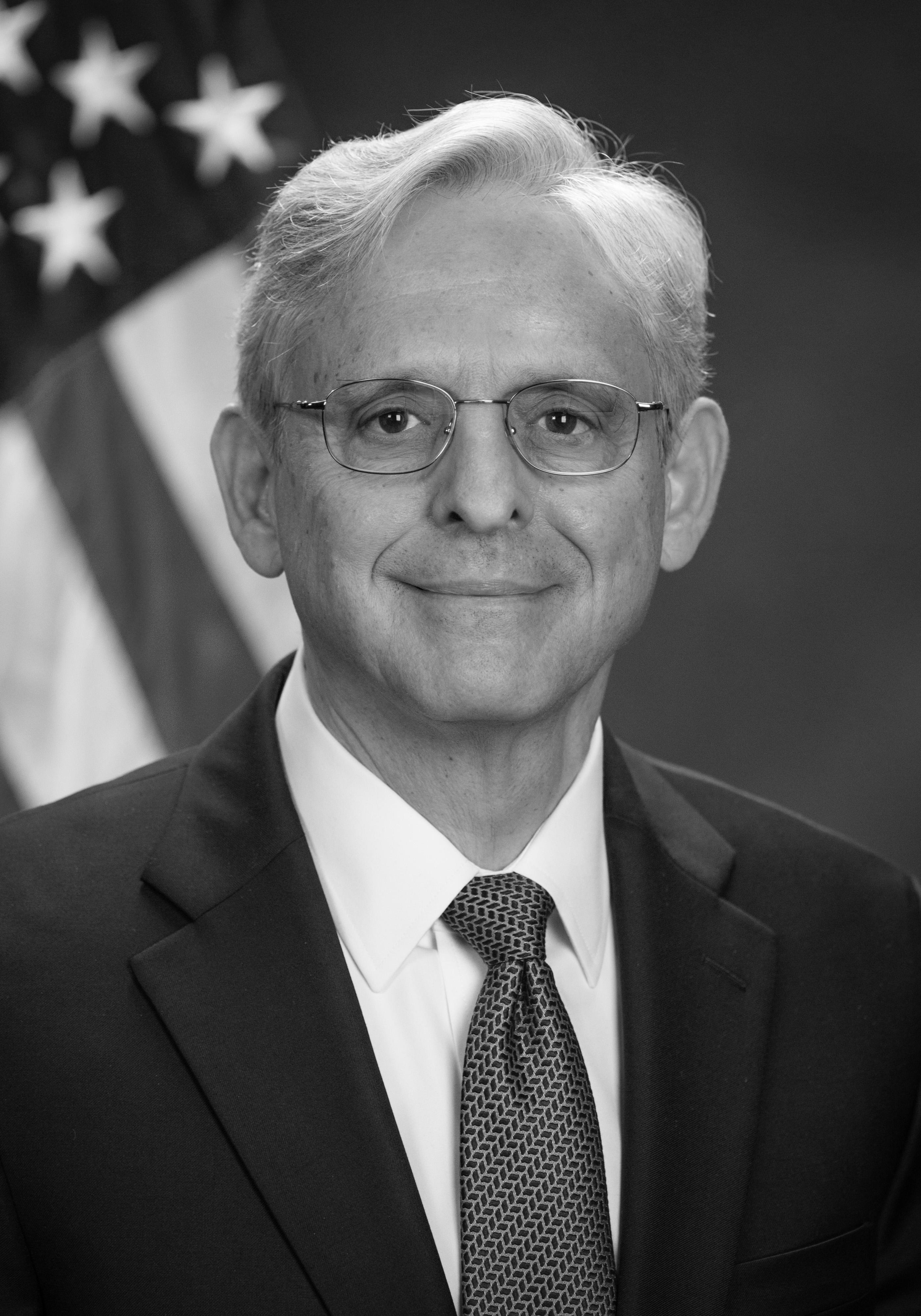

Merrick Garland, America’s Lawyer

PAGE 8. In interviews with 11 friends, former classmates, and professors, Merrick Garland ’74 was characterized by his deep intellect, honesty and dependability, and ability to get along with everyone.

braved the sleet and the cold to chant and picket outside of Mass. Hall.

PALC alleged Harvard’s investments in firms operating in Angola “facilitates the daily slaughter of Africans” and that “Harvard is deeply implicated in this crime.” The newly-elected Harvard President Derek C. Bok had resisted student calls for divestment from Gulf Oil, despite escalating protests.

“There is no question in my mind that Portugal has inflicted grave wrongs on Black people in Angola and Mozambique. The question for Harvard to consider in the next few weeks is the most responsible position for Harvard to take as a shareholder in a company doing considerable business in those two countries,” Bok said in February 1972. Still, he did not commit to a change in the University’s holdings, which were at the time still managed by State Street.

On April 14, 40 demonstrators gathered outside Mass. Hall to demand that Harvard pay reparations to the Angolan people.

Three days later, 50 members of the African Research Group and Harvard Radcliffe New Ameri-

SEE ‘ENDOWMENT’ PAGE 6

The Supreme Court wouldn’t declare affirmative action constitutional until 1978, four years after the Class of 1974 graduated. But conversations around race-conscious admissions and merit began much earlier, when Harvard’s Class of 1974 was still on campus. Between debate over affirmative action, the inception of an Afro-American Studies department, and the rise of student activism and groups like the African and African American Resistance Organizations, the Class of 1974 went through Harvard at a pivotal time in the history of race relations and Black students on campus.

‘An Overhang’ In 1974, Harvard declared it was firmly on the side of race-conscious admissions.

Marco DeFunis had sued University of Washington Law School and Charles E. Odegaard, the university’s president, alleging that the school had denied

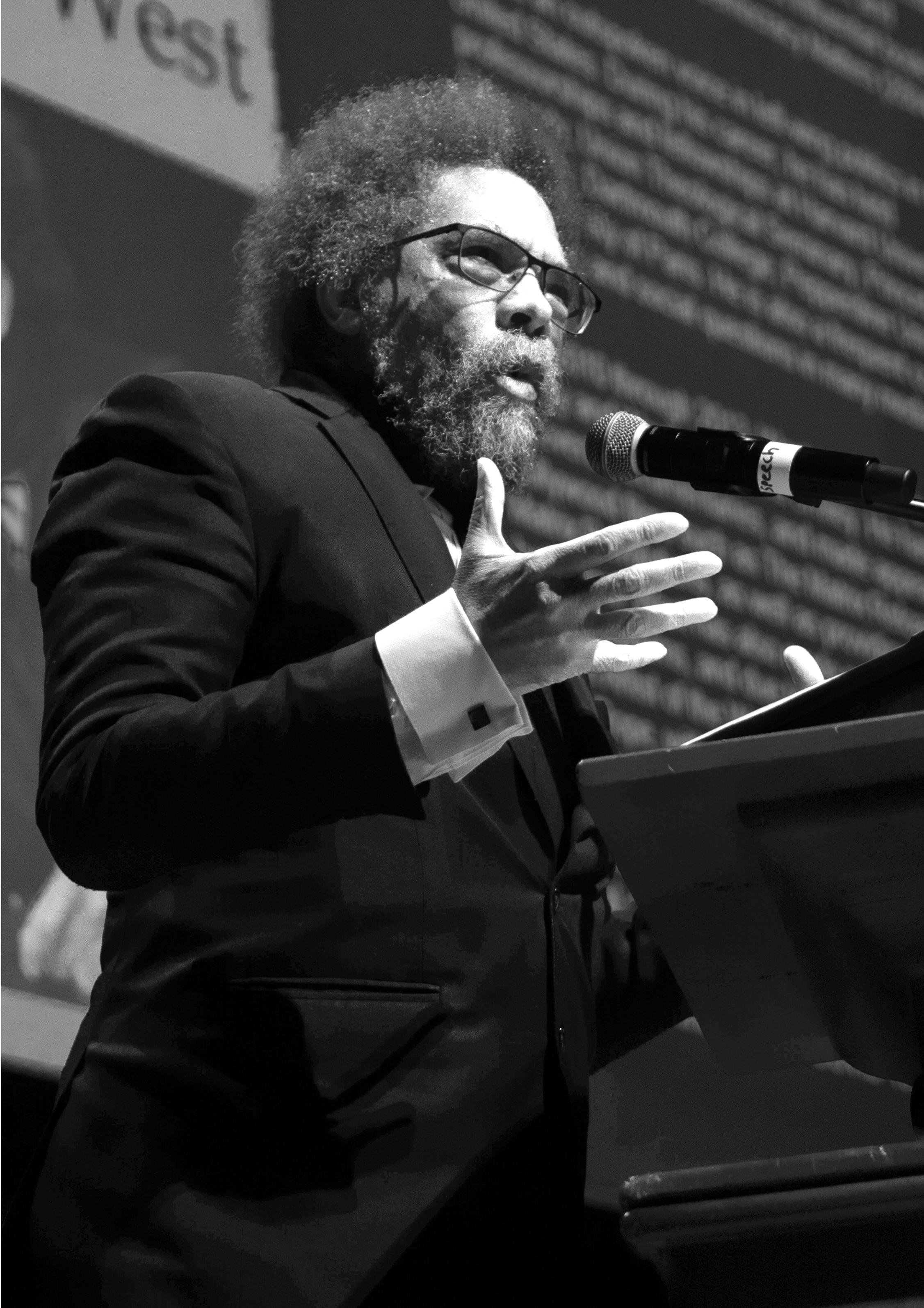

PAGE 9. Cornel R. West ’74 went from a studious Harvard student who brought books to parties to a revered Harvard professor, and later, an independent candidate for U.S. president.

him admission unfairly as he had higher test scores than white applicants. Odegaard v. Funis would find itself at the Supreme Court — and Harvard would be a force on Odegaard’s side.

The University would file an amicus brief with 25 other institutions in support of Odegaard, and its top law professor Archibald Cox ’34 — who Richard Nixon had fired as the Watergate special prosecutor in the “Saturday Night Massacre” months earlier — would be giving the oral arguments.

But while Harvard’s commitment to affirmative action in Washington was strong, its Black students on campus still had to contend with adversity on multiple fronts.

For one, the Black student population was dwindling, despite a promise from the University in 1968 to increase the representation of Black students in the College’s admitted class.

From 1969 to 1971, Harvard admitted around 100 Black students every year. But from 1972 to 1974, the number of Black students at Harvard decreased by about 25 percent.

Those who were on campus said their experience was also

tinted by critics of affirmative action who said the students Harvard was admitting were “unqualified.”

“The idea that we weren’t qualified was kind of an overhang while we were there,” said Steven C. Pitts ’74. But Pitts said that undergraduates widely recognized that the lack of Black students was more a “function of racism” than it was evidence that they were unqualified to attend Harvard. The hostility toward affirmative action wasn’t just from outside Harvard’s gates. Martin L. Kilson, Harvard’s first tenured Black faculty member, argued that elite schools had lowered standards to increase Black student enrollment.

Richard J. Herrnstein, a Psychology professor, went even further, publishing an article in The Atlantic that argued a person’s I.Q. is genetically determined. The subtext of Herrnstein’s argument was that Black individuals were inherently less qualified than their white counterparts. Herrnstein did not go without objectors; in fact, the article sparked immediate backlash from students and faculty at

PAGE 7

PAGE 12 Harvard University and Radcliffe College merged their athletics departments in response to Title IX, foreshadowing the “non-merger merger” of the two just a few years later.

Sept. 11, 1973

COUP IN CHILE. A military junta overthrows the Chilean government, leading to the death of president Salvador Allende and the installation of General Augusto Pinochet.

Sept. 24, 1973

THE SHUTLLE LAUNCHES. A free-of-charge overnight bus begins running between the Quad, the Yard, and Harvard Business School, every night from 4 p.m. to 2 a.m.

Oct. 6, 1973

YOM KIPPUR WAR BEGINS. Egypt and Syria launch an attack on Israel, sparking a conflict in the Middle East that would last approximately three weeks.

Oct. 17, 1973

KISSINGER WINS NOBEL PRIZE. For his efforts in negotiating a ceasefire in Southeast Asia, U.S. Secretary of State Henry A. Kissinger ’50 wins the Nobel Peace Prize alongside North Vietnamese leader Le Duc Tho. The choice was widely criticized, and two members of the committee resigned in protest.

Oct. 20, 1973

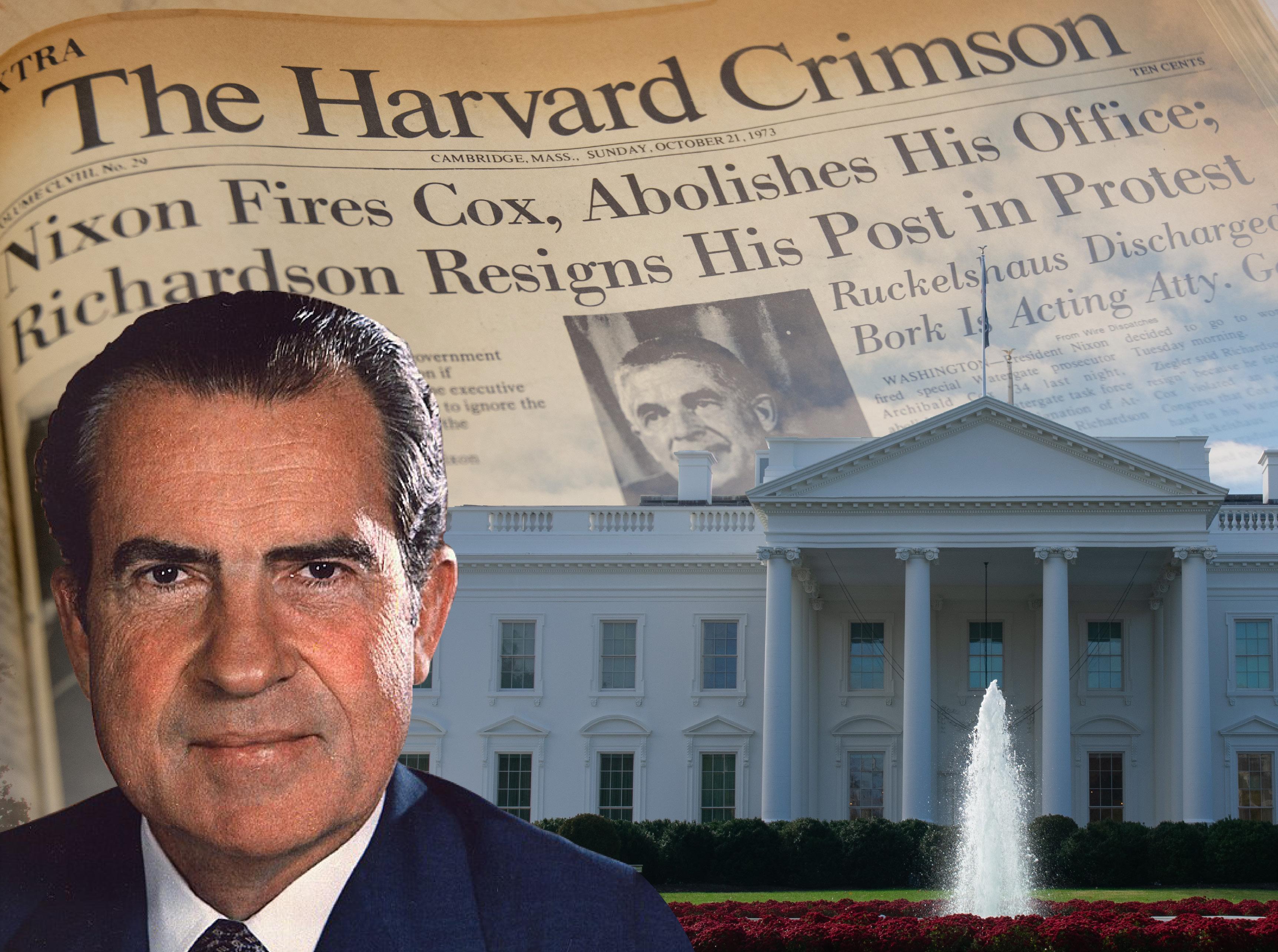

SATURDAY NIGHT MASSACRE. Richard Nixon fires Watergate special prosecutor Archibald Cox ’34, sparking the resignations of Attorney General Elliot L. Richardson ’41 and deputy attorney general William D. Ruckelshaus.

Dec. 12, 1973

COMSTOCK DIES. Radcliffe College’s first full-time president Ada L. Comstock Notestein — who served from 1923 to 1943 — dies at the age of 97 in New Haven.

Jan. 14, 1974

HOT OFF THE PRESS. After over two years of outsourced printing, The Crimson returns to printing its newspaper in-house with the delivery of new offset presses.

Feb. 11, 1974

BEANPOT VICTORY. For the first time since 1969, Harvard wins the Beanpot tournament, defeating Boston University 5-4 in the final.

Feb. 13, 1974

PILOT FOR BOSTON. For the first time, Harvard and the City of Boston reach an agreement where Harvard will give Boston an inlieu-of-taxes payment. The agreement is similar to one Cambridge and Harvard reached fifty years earlier.

April 9, 1974

STRIKE BEGINS. More than 30 workers at the Harvard University Printing Office go on strike after Harvard rejected their proposal for wage increases.

April 25, 1974

CARNATION REVOLUTION. After 41 years of control under two successive dictators, Portuguese leader Marcello Caetano is overthrown by members of the military in the Carnation Revolution.

May 18, 1974

NEW NUCLEAR NATION. India becomes the sixth nation — and the first outside of the permanent members of the UN Security Council — to test nuclear weapons.

THE NIXON YEARS.

President Richard Nixon’s Watergate scandal defined senior year for many in the Class of 1974.

BY S. MAC HEALEY AND JO B. LEMANN CRIMSON STAFF WRITERSenry S. Richardson ’77

Hwas spending his weekend rock climbing in New York when his father, the United States Attorney General, quit his job.

It was Oct. 20, 1973, and Richard Nixon had just asked Richardson’s father, Attorney General Elliot L. Richardson ’41, to fire Watergate special prosecutor Archibald Cox ’34. Richardson had refused and resigned, setting off the chain of events known as the “Saturday Night Massacre.”

“I was rock climbing in New York State for the holiday weekend, and didn’t learn of the event until I returned to campus on Monday,” Richardson wrote in an emailed statement. “By that point, the nation’s eyes were on DC.”

The “Massacre” would be a pivotal point in the Watergate saga. As the Class of 1974 began their senior year at Harvard, the scandal that would culminate in Nixon’s August 1974 resignation reached a fever pitch.

“If you were writing a script for a political movie, you couldn’t have done a better job than the reality of what was going on,” said Dan A. Swanson ’74, a former Crimson president. “The timing, the characters, it was just perfect really.”

While the Watergate break-in happened in the late summer of 1972, as the Class of 1974 finished their sophomore year, the scandal’s most dramatic moments would come during their final year in Cambridge — at a campus that had deep ties to, and was often the scorn of, the embattled administration.

‘Zero Trust or Respect’

When the Class of 1974 stepped on campus in the fall of 1970, the University was one year past the peak of Harvard’s Vietnam protest, the 1969 occupation of University Hall. The violent response ultimately contributed to the resignation of Harvard’s president Nathan M. Pusey, Class of 1928, who would be succeeded by Derek C. Bok.

“When I arrived at Harvard in 1970, I mean the campus in Cambridge were, I don’t want to say on fire, but on fire in so many respects,” said Philip N. Angelides ’74. While the war was firmly winding down by the time news of Watergate broke — and American involvement had ended by January

of 1973 — Vietnam was still on the mind of Harvard students.

Lawrence F. O’Donnell Jr. ’74 said that even after the Watergate story broke, it was the “second most important thing happening at that time,” since male students were still facing the possibility of the draft.

“It’s an indescribably large concern that I think would be virtually unimaginable to students today,” O’Donnell said. “Imagine that every male student at Harvard in those days — if it were now, it would be all students — have a draft card in their pockets, a little card the size of a driver’s license that can end their life or not.”

“That renders every other thing in the news to a lesser urgency level than the Vietnam War,” he added.

But despite the war entering its twilight years, Nixon remained deeply unpopular at Harvard.

“Nixon was widely reviled. He was really hated by the student population,” said Peter Shapiro ’74, a former Crimson managing editor. “I’m sure there were some students at that time who liked Nixon, but they shut up because they wanted to stay safe.”

The president, O’Donnell said, “had certainly zero trust or respect from any Harvard student who I knew.”

The animosity was mutual.

The Nixon administration, for its part, focused its ire on the University’s faculty and administration. Several top Harvard professors and administrators were on the President’s list of opponents, an expansion of his initial 20-person

“Enemies List.” The list included Bok — who was still dean of Harvard Law School — along with former Faculty of Arts and Sciences Dean McGeorge Bundy and the presidents of Yale University and MIT.

“Harvard as a news reporting subject was very much involved in the Nixon administration,” Steven M. Luxenberg ’74, a former Crimson associate managing editor, said. “So we saw those Harvard ties as reporting opportunities.”

Still, Nixon had some Harvard allies. Along with Richardson, Nixon appointed several other Harvard alumni to his Cabinet, and appointed FAS Dean John T. Dunlop to serve as the director of the Cost of Living Council. He also deeply relied on the counsel of Harvard professor Daniel Patrick Moynihan as well as Henry A. Kissinger ’50, a Government professor who would serve as his national security adviser and secretary of state.

‘A Spectator Sport’

Though burglars broke into the Watergate Complex on June 17, 1972, the brewing scandal took time to engross the general public.

“It just wasn’t much of a story,”

Angelides said. “As Nixon said: ‘If it’s not on TV, it doesn’t matter.’”

But, as the scandal began to rapidly unfold, the major news stations started airing the Senate’s hearings on Watergate each night to a rapt national audience. The hearings were filled with madefor-TV-moments and put witnesses and senators, like the committee’s chairman Sen. Sam J. Ervin (D-N.C.), in the limelight.

In one particular landmark moment, Nixon’s special assistant Alexander Butterfield revealed that the White House was bugged — a moment O’Donnell said he’ll “never forget.”

“Every minute of the Watergate hearings, we were watching on TV,” O’Donnell said. It would be a chaotic autumn.

Angelides distinctly recalled one night in October of 1973, when “they were covering what happened in Watergate, the Israeli-Egyptian war that had broken out — the ’73 Yom Kippur War — and thirdly, Spiro Agnew resigned as vice president,” he said. Agnew had resigned as Nixon’s Vice President on Oct. 10 over allegations of tax crimes came to light.

“

it propelled a lot of us to be in public service.” Swanson said that as the Watergate saga unfolded, protests over Nixon’s policies dissipated as well.

“This didn’t happen overnight, but it went from a protest in the street to a spectator sport,” he said.

“People were cheering on Ervin.”

‘Nixon Will Have to be Impeached’

The drama would reach a head when the “Saturday Night Massacre” unfolded on Oct. 20, 1973, just 10 days after Agnew resigned.

It was dramatic. After Cox — the Harvard Law School professor-turned-Watergate special prosecutor — refused Nixon’s request to drop his subpoena of the White House tapes, Nixon asked Attorney General Elliot Richardson to fire Cox.

Richardson refused and resigned. His second-in-command, deputy attorney general William D. Ruckelshaus, also refused — and while Ruckelshaus said he resigned, Nixon’s press secretary Ronald L. Ziegler said he was fired.

I’m sure there were some students at that time who liked Nixon, but they shut up because they wanted to stay safe.

Peter Shapiro ’74 Former Crimson Managing EditorAngelides said that “every night” he would go from the Dunster House dining hall to catch the hearings.

“Every night we would rush out of the dining hall to make sure we caught the CBS Evening News to find out the next thing that had happened with Watergate,” Angelides said.

Along with Butterfield, the Senate’s hearings featured other high-profile witnesses from the Nixon administration, many of whom — like Butterfield — provided landmark testimony. Some of the most memorable testimony came from John Dean, who served as the White House Counsel, when he directly implicated Nixon in the scandal.

“When John Dean gave his bombshell testimony, I think the general feeling was that this was sort of the beginning of the end for Nixon,” said Peter M. Shane ’74, a former Crimson editor. “Not that anybody had a crystal ball.”

“Was Watergate a huge part of our lives? It was huge,” Angelides said. “Everyday we consumed the papers. We watched it on TV. And

The third in line, Solicitor General Robert Bork, would ultimately comply, and Cox was fired.

The event was so massive — and would turn out to be so damaging — that The Crimson published an extra edition that Sunday.

“Because the two main people fired had Harvard ties — one was a Harvard professor — it felt like we were delivering news to the campus that was wanted and needed and delivered in a way that was different than the New York Times or the Washington Post,” Luxenberg said.

It was a devastating moment for the administration, which was rapidly losing support. John Kenneth Galbraith, the famed economist and Harvard professor, told The Crimson at the time that “Nixon will have to be impeached. I was reluctant to say it until now, but this is it.”

The Harvard connection, too, was not lost on members of the faculty. All three casualties of the Saturday Night Massacre had Harvard ties: Cox was a College alum and a longtime HLS profes-

sor, Richardson was also a College alum, and Ruckelshaus was a graduate of the Law School.

“We’re very proud of them all, proud of the role of Harvard men in government,” then-FAS Dean Henry Rosovsky told The Crimson. The Class of 1974 would invite Richardson to give their Class Day address, which he did just months before Nixon ultimately resigned.

Just 10 days later, members of the House would introduce impeachment proceedings. The Crimson, though, had reported that the proceedings were viewed as “inevitable” by the Speaker of the House himself a week earlier: “Speaker of the House of Representatives Carl Albert sees impeachment proceedings against President Nixon as ‘inevitable,’ his son David E. Albert ’77 said yesterday,” the article read.

The first half of 1974 brought perilous legal developments for Nixon and his inner circle. In March, a grand jury indicted Nixon’s closest associates, including his chief of staff H. R. Haldeman and former Attorney General John N. Mitchell. Just over a week later, Gerald Ford, Agnew’s successor as vice president, was protested arriving at the Harvard Club of Boston where he would receive the Harvard Republican Club’s “Man of the Year” award.

“As a drama, there was an inevitable flow to it,” O’Donnell said. “It was only flowing in one direction. It was never heading into a spot where it looked like Nixon was going to survive.”

The climax of the saga would come very soon after the Class of 1974 graduated. After the Supreme Court unanimously ordered the White House to turn over its tapes in July, the “smoking gun” tape — in which Nixon’s knowledge of the Watergate cover-up became public — was released on August 5. He resigned just three days later.

“My college roommate was in France for the summer. And I wrote to her and said I just feel that our system of government is working exactly the way it’s supposed to and it’s just a thrill,” said Dale S. Russakoff ’74, a former Crimson editor. “I felt thrilled.”

50 Years Later

Fifty years later, Watergate has cemented a position in the American political consciousness. Members of the Class of 1974 said that looking back, the moment had a profound impact on their career trajectories — and their views on today’s fractured politics.

For some members of the Class of 1974, the era spurred careers in politics and activism.

“I could probably count on one hand the number of my classmates who wanted to go work on Wall Street,” said Angelides, who would later become California’s

JULIAN J. GIORDANO — CRIMSON PHOTOGRAPHER

state treasurer. “It was part of the ethos of the era that public service and political engagement was held in very high esteem, and viewed as a very worthy goal for young people.”

“The Nixon era and the Watergate era is really what propelled me into a lifetime of activism,” he added.

Others drew inspiration from the journalists at the heart of the Watergate story.

Luxenberg, who was on The Crimson, said he took particular inspiration from Washington Post journalists Bob Woodward — who would later become Luxenberg’s boss — and Carl Bernstein, whose reporting on Watergate played a crucial role in the downfall of the Nixon administration.

“As a young reporter — someone who hoped to be a reporter — I thought, ‘Wow, I better pay attention here,’” Luxenberg said.

“Watergate’s very much been a part of my experience, but really from a journalist point of view, not from an advocacy point of view,” he added.

A’Lelia Bundles ’74, who also became a journalist after graduating, said that Watergate helped shape her career path.

“There was just such an excitement about being a journalist at that time that you really could change the world, that journalists had toppled a president,” Bundles said.

“It was at that moment, right after Watergate, that that was the kind of journalist that I wanted to become,” she added.

O’Donnell, who would later become an MSNBC anchor and producer of the hit TV show The West Wing, said that the Watergate era was an influence on the show.

“I think it’s one of the reasons why Aaron Sorkin, who created the show by writing the first episode, wanted to see the kind of president he wishes were actually president,” he said.

But for some, the drama of Watergate — and the Nixon administration’s actions — still pale to today’s political landscape.

“What looked like a crisis 50 years ago is really tame compared to where we are now,” Bundles said.

Angelides agreed, saying that America’s present-day political situation is different from the volatile political situation in the 1970s.

“At the time I thought America was on the precipice of danger,” he said. “I never could have imagined when I was that Harvard junior, Harvard senior, that we would face the kind of threat to our democracy and our nation that we’re facing today.”

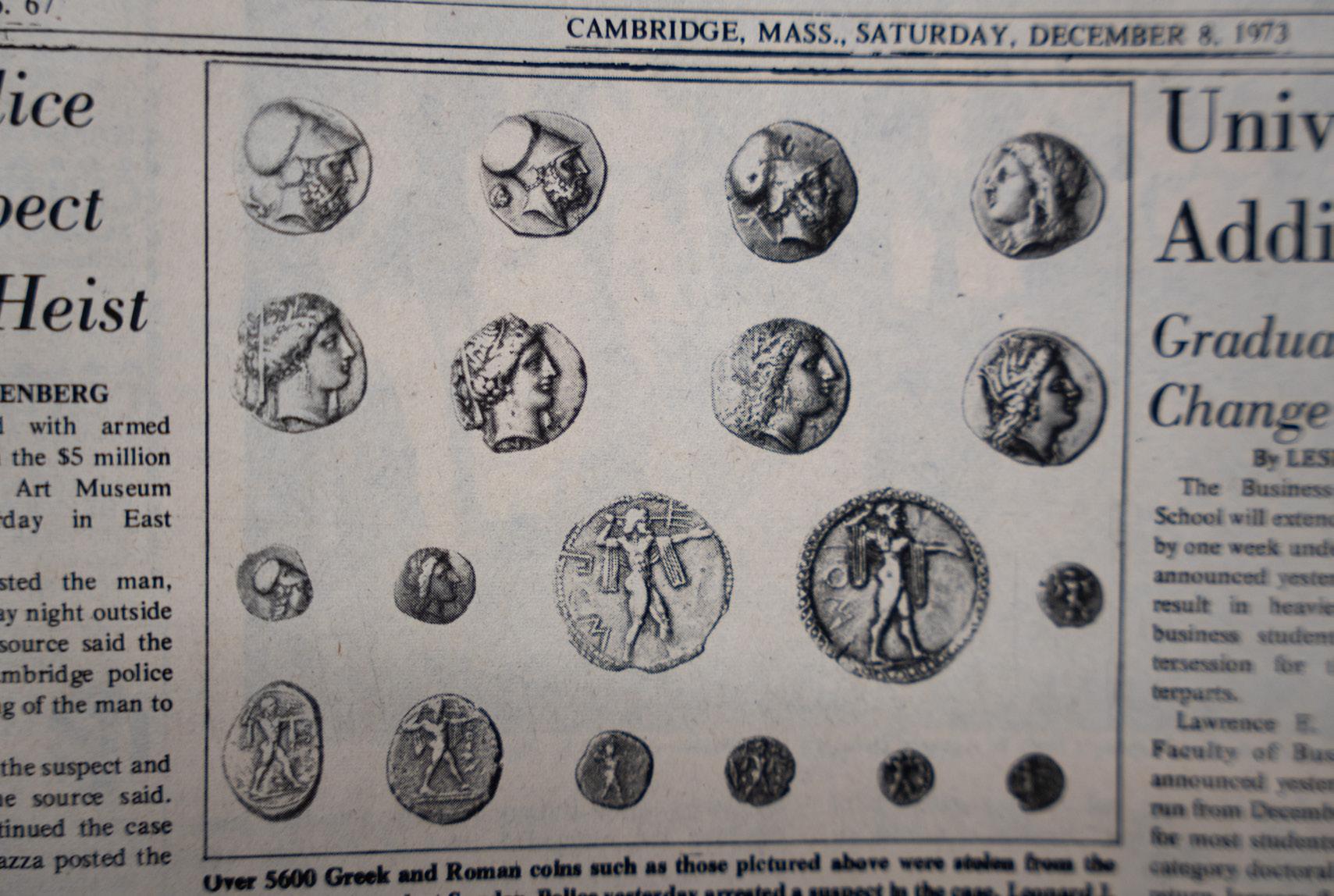

century B.C.E. and the fourth century C.E., the silver, gold, and bronze coins were worth approximately $2 million — more than $8.5 million today. A University press release after the theft said they were a “fundamental” and “irreplaceable” part of Harvard’s teaching collection.

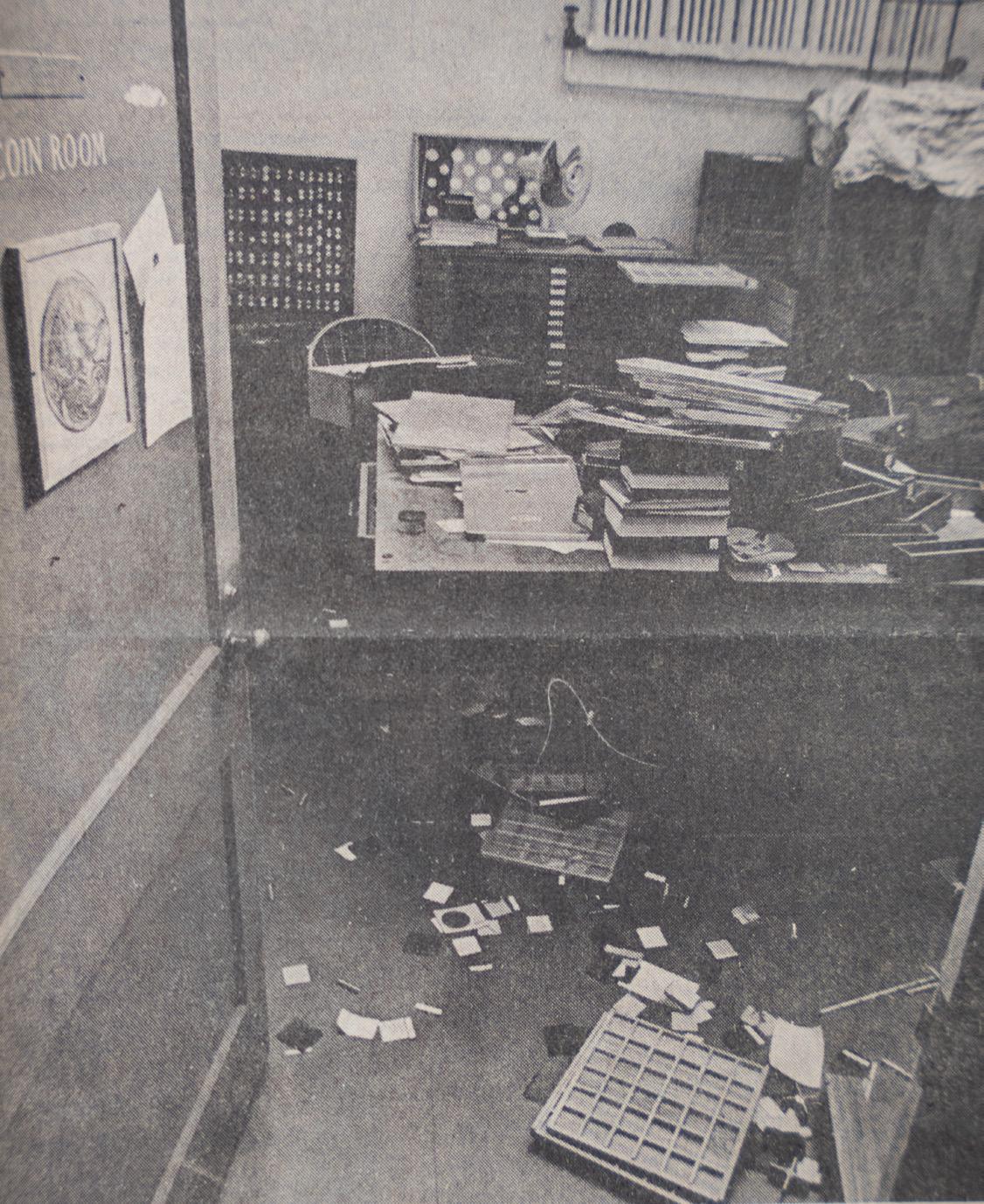

On a December night in 1973, five armed men broke into Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum and stole more than 6,000 ancient Greek and Roman coins — an incident that The Crimson reported at the time was “believed to be the largest art theft in U.S. history.” Minted between the seventh

In the following months and years, the University and federal law enforcement mobilized to find and catalog the missing coins. With the work of more than 40 FBI agents assigned to the case, approximately 85 percent of the original collection has since been retrieved. Still, the theft’s legacy lives on in the minds of art enthusiasts. Laure

Marest, the current associate curator of ancient coins at the Harvard Art Museums, said the “traumatic” event continues to be remembered by museum staff.

A Nighttime Robbery

On Dec. 1, 1973, a 20-year-old man left a brown paper bag labeled “Coop” with the Fogg Museum security guards.

A few hours later, after the museum had closed, a guard received a call from a “Mr. Ryan” claiming that he had forgotten his bag and would be coming around to pick it up. When the man came to pick up the bag at around midnight, he produced a revolver.

A simple pickup quickly transformed into an armed robbery.

Four other armed men followed the supposed Mr. Ryan, taking the guard’s key ring to the coin room and smashing open the cases.

As none of the thieves were art historians, they also mistakenly broke into display cases holding replicas of coins actually held in the British Museum before realizing that they were fake and had no backside.

The Fogg Museum didn’t know what would happen to the stolen coins: whether they would be distributed across the country, sold at auctions, buried in backyards, or even melted down for their gold and silver content.

A few months after the theft, authorities found more than 3,000 of the stolen coins buried in Rhode Island. Less than one month later, more than 800 coins were found in Montreal when police arrested an American art smuggler.

As coins were returned to the Fogg, museum staff and graduate students at Harvard worked to identify and catalog them — a difficult task given the lack of photo doc-

umentation or even a complete list of the original coin collection.

Meanwhile, the police investigation continued and, in 1976, the thieves were brought to trial and convicted. In 1979, five-month investigation culminated in the State Police working with an informant to uncover an additional 2,883 coins.

This brought the total number of recovered coins to 6,773, which has remained largely unchanged since. Over the past four decades, a few small coin discoveries have been made, including in 1994, when a building custodian found one coin under the edge of the rubber carpet in the coin room.

Completing the Collection

Fifty years after the theft, the Harvard Art Museums has beefed up

security and is now embarking on a new plan to retrieve the roughly 15 percent of stolen coins still missing today.

After her appointment as the associate curator of ancient coins in 2023, Marest initiated a two-part plan.

Phase one entailed working with graduate students to build an online inventory based upon photographs of part of the collection, while phase two involved hiring computer science students to comb through art auction listings from the past 15 years to find matches using artificial intelligence.

According to Marest, when the coin investigations were still ongoing in the 1970s, there were no “aggregated databases.”

“So checking to see if anything would show up on the art market would entail manually checking ev-

ery single auction catalog and also having an incredible visual memory,” she said. The advent of AI simplified the task. Marest said the plan is “only possible now with those databases.”

With most of the coins recovered, visitors can view parts of the collection in the Harvard Art Museums’ permanent exhibition — and even request to hold many of the formerly stolen coins with their hands. Despite the public access, the Harvard Art Museums isn’t taking any chances. When asked about the updated security measures, Marest shook her head and said, “I can’t discuss that.”

can Movement protested Portuguese colonialism at the Harvard Club of Boston. Three days after that, on April 20, students would use crowbars to break into Mass. Hall to begin their occupation.

“This is before it was common to speak of things of thinking globally and acting locally. Just giving life to slogans like that, in an onward struggle of humanity and a better world,” said David L. Dance ’74, who was part of the group who helped organize the occupation. In a joint statement issued the morning of the occupation, the Harvard-Radcliffe Association of African and Afro-American Students and the PALC demanded from Harvard “a public statement that it will not be involved in racist imperialist adventures in the future.”

“We feel that Blacks at Harvard are not getting anywhere with petitions and discussions,” AFRO president Kevin J. Mercadel ’74 said at the time. “So we are adopting direct action, direct tactics.”

As the occupation stretched into the night, approximately 2,000 students gathered in Sanders Theater and voted “overwhelmingly” to support PALC’s demands, according to an article in The Crimson. Over the following week, the occupiers continued to maintain student support.

“We built up roughly 2,000 people demonstrating in Harvard Yard,” Dance said.“And then crosses were set up in the interim, to represent the folks who were dying as a result of the struggles in southern Africa.”

When they finally vacated Mass. Hall, the students clothed the John Harvard statue in the outfit of a Ku Klux Klan member.

“Our ultimate decisions in terms of how to come out of the building just involved getting some white bedsheets together and dressing John Harvard up in the Klan’s outfit and vacating the building,” David said.

Despite the protests, George F. Bennet ’33 — who managed Harvard’s endowment prior to HMC’s founding as the president of State Street — held a “consistent view” that firms should not

interfere in the management of the companies they invested in, according to Daniel A. Swanson ’74, a former Crimson president who covered the Mass. Hall occupation as a reporter. “If you own shares, you have no business interfering in the day-to-day or week-to-week strategy management of the company,” Swanson said, describing Bennet’s investment approach. “The key thing here is he had a consistent position.”

Still, Swanson said the protesters’ primary goal was to spread awareness that Portuguese colonies remained in Angola — not to necessarily force

Harvard to divest its holdings in Gulf Oil, which it never did.

“Nobody was stupid enough to think it was going to mean that Angola was going to become independent overnight,” Swanson said. “The whole point was to get publicity surrounding this issue so that people would know.”

“So the protest worked, not totally, not completely — it worked,” he said.

The Creation of the Company

While the protests over Harvard’s holdings in Gulf Oil did not directly lead to the founding of the HMC, they likely put pres-

sure on the University to establish a managing corporation.

“I would speculate that the protests might have accelerated a decision making process about creating a management company that was already underway,” said Robert W. Decherd ’73, who, like Swanson, was a former Crimson president who covered the occupation as a reporter.

More directly, the occupation led to the creation of the Advisory Committee on Shareholder Responsibility. Bok established the Committee in 1972 to advise the Corporation on the impacts of their investments. According to the University, the Committee

was established “concerning the social and ethical implications of the choices it must make as a major shareholder in many companies.” The ASCR proved itself to be a prominent force in advising the Corporation on how to manage its money.

Just two years later, the HMC would be founded. Crucially, HMC employees would not be allowed to serve on corporate boards for any of the companies in which Harvard was invested, a marked shift from the previous policy. Bennet, the former University treasurer and State Street president, served on several corporate boards.

Walter M. Cabot ’55 — the HMC’s first president and deputy treasurer — said he believed Bok wanted the University to have greater authority over its endowment.

“I think the University and Derek Bok wanted more control over the management than what was provided by State Street,” Cabot said. A Crimson article from 1974 mentions that “Bok and most of the members of the Corporation found themselves at odds with Bennett’s attitudes toward shareholder responsibility, investment policy and other aspects of Harvard’s financial dealings.”

With Cabot in charge, HMC would “try to avoid putting Harvard money into companies which, in their opinion, are not socially responsible,” The Crimson wrote. While Cabot did not recall the HMC adapting its investing strategy to respond to the Angola protests, he said the company did focus on pushing firms to lessen apartheid in South Africa under his leadership.

“Apartheid in South Africa was a big issue,” Cabot said. “Harvard never did divest, but we did put pressure on companies to reduce the pressure of apartheid and we were selective in our portfolio.” The HMC’s creation created a new focus for student protest. For the past five decades, students have protested against Harvard’s holdings in all sorts of nations and industries, most notably in apartheid South Africa, fossil fuels, and Israel. Though the protests did not completely change Harvard’s approach to investment or the founding of the HMC, Dance still said the students who risked their Harvard careers played a pivotal role in raising awareness of the Portuguese holding of Angola.

“At every moment, it’s all about a struggle for consciousness,” Dance said. “That’s very often just the role — the catalyst to raise consciousness to another level.”

The Harvard University Printing Office has been shuttered for over 20 years. But in the spring of 1974, the Office dominated the local news. More than 30 printers — members of the Graphic Arts International Union — began picketing in April after Harvard rejected their proposal calling for a 5.9-percent wage increase plus a weekly $10 across-theboard pay raise by May 1. They were joined by five employees of the Typing and Copy Center on April 24. For three months, the strikers protested across campus. They rallied at an alumni fund banquet, demonstrated outside a 25th reunion event for the Class of 1949, and garnered support from students, faculty, and local labor leaders.

The strike would receive national attention: John F. Henning, the executive secretary-treasurer of the California Labor Federation, AFL-CIO, refused to give a speech at Harvard Business School’s trade union program’s graduation ceremony and instead joined the printers on the picket line. The Crimson predicted that Cesar Chavez, the famed labor leader, would picket with the Harvard printers on strike. But while the strike dominat-

ed the front pages of The Crimson, it has largely faded from memory. After its conclusion in the summer of 1974, just one Harvard Magazine article in 2002 — when the 130-year-old Printing Office closed — provides a readily accessible record. Additionally, while the union had called on Boston-area printers to boycott the exams, it stopped short of calling for students to join the boycott, in the belief that there would not be enough time to organize a student boycott.

According to some Harvard students at the time, the strike was not at the forefront of most of their minds.

“Labor movement-type activity was very second-order in the minds of students,” said Nicholas B. Lemann ’76, a former Crimson president who covered the strike.

“The impression I took from those years was that number one on the sort of organizing and protest agenda was Vietnam,” Lemann added. “Everything else was in a subordinate position.”

Luther M. Ragin ’77 — who as an undergraduate helped coordinate between student groups who wanted to protest with the workers — said that “the labor issues were more niche,” not “the mass movements that the Vietnam War were or the South African anti-apartheid movement were.”

Still, the strike commanded the attention of many — at least hundreds of students and dozens of faculty, according to Ragin. Students for a Democratic Society and the New American

Movement — student organizations who played an important role in organizing Vietnam War protests just a few years earlier — helped lead the strike. Collaborating with non-Harvard groups such as the Spartacist League and Revolutionary Communist Youths, they circulated petitions and demanded meetings with then-Harvard President Derek C. Bok.

The Harvard Chapter of the Union for Radical Political Economics, whose membership included 25 Harvard professors and graduate students in economics, also supported the strike, arguing that Harvard’s wage increase offer of 5.5 percent was not sufficient given the monthly increase in inflation of 12.8 percent.

The University and John B. Butler, its director of personnel, sought not to cave in to the strikers’ demands, even though outsourcing printing cost Harvard an estimated $12,000 per week for its duration. As workers picketed outside the Printing Office, the University spent $300 a day for a special watch of the Office by three Boston Police Department officers.

“The problem was that they were small,” Ragin said. “Harvard could ignore them because they were small, and even penalize them by basically sourcing printing to other sources.”

This caused the printers to turn to students who were “sympathetic” towards their issues, he added.

Harvard, in response to the strike, argued its 5.5 percent offer was fair and touted the “superior” benefits and stability it offered employees. Workers soon began chanting “Can’t survive on

5.5!” as they rallied on campus.

“It was very clear that this was kind of a precedent that the university was trying to set as a marker or benchmark for its upcoming negotiations with other Harvard labor unions,” Ragin said.

Come final exam season, the strike posed a significant risk to University activities. If there were no printers, the University would not be able to print out tests.

Harvard decided to print them in off-campus shops employing non-union workers, according to the Harvard spokesperson at the time.

After months of action, the strike ended quietly in late July. But the University still faced challenges with the striking printers.

Carl W. Getz Jr., director of the University Printing Office at the time, told The Crimson that formerly striking printers were doing about “half of the volume of printing” post-strike as they were doing before. Getz said that he had to “boost morale” among recently striking employees, and the printing office had to “sell itself within the University” in order to regain business.

While much of the story of the strike and the workers at the printer’s office has been in some ways lost to time, Ragin says its impact was outsized.

“There absolutely was a sense that this was more than just a relatively minor labor dispute,” Ragin said. “It was something that had much broader implications for Harvard staff, and the Harvard community at large.”

adithya.madduri@thecrimson.com

saketh.sundar@thecrimson.com

LIVING WAGES. Workers at the Harvard University Printing Office went on strike in 1974, sparking national attention. Harvard and elsewhere. The Progressive Labor Party protested Herrnstein’s employment and the employment of other Harvard professors who shared racist beliefs.

“We would have educational programs, we would have demonstrations and try to get those people out of Harvard,” said Esther V. John ’74-’76, a PLP member. Other organizations, such as the Organization for the Solidarity of Third World Students, took matters into their own

We study the Black experience from the

hands. In its time, OSTWS developed an affirmative action task force to analyze racial diversity and equity in Havard’s hiring processes in the face of affirmative action controversies. Still, such criticism increased the pressure that many Black students at Harvard felt to justify their standing at the university.

A’Lelia Bundles ’74 said that she never felt as though others looked at her and said she was “unqualified” to attend Harvard. Still, she said “there were always people who wanted to derail” actions Harvard had taken to increase the Black student population and make them feel welcome on campus. Bill G. Fletcher Jr. ’76, a member of OSTWS, said that “most of us felt that we had to always demonstrate that we really were worthy of being at Harvard.”

‘A Questionable Status’

As students protested the views of their professors, Harvard itself also expanded its academic offerings in African and African American Studies — then called Afro-American Studies. In 1969, Harvard established its Department of Afro-American Studies. The College then first offered a field of concentration in Afro-American Studies in 1972. Chris H. Foreman ’74 said the department had a “fragile status” on campus — in part because of the opposition of Kilson. Kilson criticized the Afro-American studies department for a lack of academic structure and discipline, affirming that students should gain a core academic background before delving into the field. He also believed that the de -

partment’s head, professor Ewart G. Guinier ’33, was the “wrong person to run it.”

The two professors would argue relentlessly, taking out pieces in the New York Times and even debating the structure of the department in December 1973 on “Positively Black,” a New York TV program.

“We must redefine Black studies so that it is not just an ideological tool giving Blacks a new sense of their worth,” Kilson said during the debate. Guinier countered: “We study the Black experience from the point of view of the people who have lived that experience.”

Foreman said the contentious debates over the department put its legitimacy into limbo.

“There was a sense that maybe it wasn’t as rigorous or wasn’t as high quality as other departments,” Foreman said. “Most departments don’t exist because students want them, they exist for other reasons, so Afro had a questionable status for a while.”

The new department had difficulty recruiting faculty members because of its lack of credibility and stature at the time. For that reason, many faculty members in the department were jointly affiliated with other academic departments at Harvard.

“I think that was kind of the bureaucratic compromise that was arrived at as a way of luring

traditional scholars,” Foreman said.

For Nethersole, who concentrated in Afro-American studies at Harvard, the fact that the department only had joint disciplinary professors had both positives and negatives.

“I became somebody who wasn’t bound by disciplinary studies,” Nethersole said. “Although I think it also undermined the legitimacy of the department in the sense that it wasn’t enough to be a professor in Afro-American Studies.” Despite the debates over the department’s pedagogy, Bundles said that its academic offerings helped her fill gaps in her knowledge of Black history and culture.

“There was a lot of unlearning I needed to do, and some of the Afro Studies literature and history courses compensated for that,” Bundles said. She said that the department’s existence was testament to the efforts of years of advocacy from Black affiliates.

“I know that there’s so many people who came before and now thousands of African American students and alumni who have come afterwards who really have made Harvard a better place,” Bundles said.

elyse.goncalves@thecrimson.com grace.yoon@thecrimson.com

LIKEABLE LAWYER. At-

BY SALLY E. EDWARDS AND JACK R. TRAPANICK CRIMSON STAFF WRITERSIf not for chemistry class, America’s lawyer may have been a doctor instead.

Attorney General Merrick B. Garland ’74 entered Harvard on the pre-med track, and together with his freshman year roommate Earl P. Steinberg ’74 began taking the requisite courses to become a doctor.

“I saw it as the best way to help people directly,” Garland, a former Crimson editorial editor, wrote in an emailed statement to The Crimson. “Unfortunately, my academic passion did not match my academic ability — chemistry foiled my plan for a career in medicine.” Steinberg suggested that Garland — who he had known since kindergarten, and would room with throughout their time at Harvard — consider going into law.

“I told him that, look, if he asked me, he ought to go into law,” he said. “I don’t think he went into law because I suggested it, but because he’s such a logical thinker, and he writes exceptionally well.” Garland’s academic skill was well established by his peers. In interviews with 11 of his friends, former classmates, and professors, he was repeatedly characterized as a man who struck others for his deep intellect — but also for his honesty and dependability, and for seeming to get along with everyone.

‘Once in a Generation’ Garland’s academic strength was hailed by those who knew him. His friends painted a glowing portrait of his “generational intellect” and talent while at the College — someone who everyone seemed to know he was going to go places in life.

“In sophomore year we lived in a quad in Quincy House and the phone rings, one day, and I answered it, and it was some professor from the Law School,” Steinberg said. The professor, who taught a Law School seminar that Garland was enrolled in, was calling to deliver a grade.

“He said, ‘I was going to give it an A plus, but it really is the best paper I have ever read by an undergraduate,’” Steinberg said. According to William J. “Jim” Adams ’69, “Merrick Garland was the kind of student, who from a faculty member’s perspective — and certainly my perspective — comes along only once in a generation.”

“He’s the kind of student who makes you believe that being a teacher is absolutely the most satisfying of all possible careers,” Adams said. Garland, who concentrated in Social Studies and wrote a thesis titled “Industrial reorganization in Britain; an interpretation of government/industry relations in the 1960’s,” would graduate from Harvard summa cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa.

‘A Guy That You Really Couldn’t Dislike’ Those who knew Garland also remembered him for his agreeable demeanor, with some noting that at a particularly politically charged time — in a particularly political house — Garland did not wade deep into controversy.

“Quincy House was the center of so much progressive activity,” said Norman “Norm” W. Gorin ’74, adding that Quincy was known for being the “political” house, full of government and economics majors — as well as progressive activism during an era of historic student protests against the Vietnam War. Quincy was also home to several other students who went into — or came from families in — government. As controversy around the Vietnam War continued and then waned in the early 70s, Garland largely stayed out of the ideological disputes prevailing on campus.

“I sometimes thought he kind of went out of his way not to be

controversial. He just sort of shied away from a lot of the disputes that might have happened around the table those days,” Jonathan M. Stein ’74 said. The young Garland would serve as the Quincy House representative to Harvard’s Committee on House and Undergraduate Life. CHUL representatives found themselves in a particularly fraught time. The University was attempting to navigate its relationship with Radcliffe College and, separately, the future of ROTC which had been eliminated at Harvard in 1969. Garland would be a vocal participant — and peacemaker — on the committee.

“While he was engaged in the moment, he was never one to be taken away with passion,” Roger W. Ferguson Jr. ’73, a friend of Garland’s, said.

“He was a very affable guy,” Stein said. “A guy who you really couldn’t dislike. I mean, everybody liked Merrick.” Garland’s peers from his time as an undergraduate also added he was — and still is — “authentic”.

“Merrick has never forgotten where he came from,” Greg A. Rosenbaum ’74, another friend of Garland’s, said. Rosenbaum pointed to both Garland’s confirmation hearings, where he “was impassioned about his family history and his life growing up,” and even just making time to host high school debate champions at the Department of Justice.

“He still took time out of his busy day to meet with and honor these urban high school policy debaters because it reflected on where he came from,” Rosenbaum said.

Ferguson, who would later overlap with Garland on Harvard’s Board of Overseers — the University’s second-highest governing body — said Garland “is what he appears to be.”

“I’ve known him for 50 years,” Ferguson said. “He’s sort of always been that way.”

‘Very Honest, Very Effective, Very Efficient’

After leaving Harvard — he would

get his law degree from Harvard Law School in 1977 after graduating from the College — Garland’s career has taken him from the halls of the Supreme Court to the Department of Justice, where he serves as the nation’s chief law enforcement officer.

He graduated from Harvard Law School in 1977, and then practiced law before pursuing a career in the Justice Department.

As principal associate deputy attorney general, Garland oversaw the prosecution of the Oklahoma City bombing case, where his senior thesis tutor Peter Gourevitch said he first appreciated his former student’s public service.

“I noticed his public fame, I think, when he was assigned to investigate the Oklahoma bombing,” he said. “The stories said that he was seen as very honest, very effective, very efficient, and very fair.”

He would then serve as a Chief Judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. During his time as a judge, President Barack Obama

appointed him to the Supreme Court to fill the seat of the recently-deceased justice Antonin Scalia. Senate Republicans, though, obstructed his nomination and the seat would be filled by Justice Neil Gorsuch. Thomas F. Brockmeyer ’74 –one of Garland’s Quincy House friends — said he found the situation “upsetting personally.”

“It just infuriated me — because of all the people that I thought would have belonged on the Supreme Court, and would have done a great job on it, he would certainly be at the top of the list,” Brockmeyer said. Upon Joe Biden’s election in 2020, though, Biden tapped Garland to serve as Attorney General, and Garland agreed. Garland wrote to The Crimson that his career in public service has allowed him to uphold and protect democracy.

“The promise at the foundation of our democracy is that the law will treat all of us alike,” Garland wrote. “Working to fulfill that promise, specifically by uphold-

ing the rule of law and helping to ensure the equal protection of law, has been the focus of my entire professional life.” Despite his schedule and illustrious career, Garland has also remained involved with his alma mater. Along with a stint on the Board of Overseers — Garland would serve a year as president of the board, too — he returned most recently in 2022, to give a commencement speech at the makeup ceremony for the Class of 2020 and 2021.

“The way I thought about it for myself was that someone who had no more right to a place at Harvard than thousands of others had an obligation to repay that piece of good fortune through service to others,” Garland wrote.

“I believe that all of us who ended up at Harvard were lucky in some way, and because of that, we have an obligation to give back by devoting some part of our lives to public service,” he added.

THE HARVARD CRIMSON C LASS OF 1974 REUNION

PUBLIC PHILOSOPHER.

The former Harvard professor and independent presidential candidate began as a bookish Harvard student.

BY CAM E. KETTLES CRIMSON STAFF WRITERCornel R. West ’74 brought a book with him just in case the party quieted down.

“He went to parties,” said Sylvester Monroe ’73, West’s Leverett House roommate. “He was a really good dancer, but one of the things I remember is even at parties, sometimes there would be a lull in the music and Cornel would have a book.”

“He always had a book,” Monroe added.

It was in character for West, who was known to be a diligent student. Throughout his time at Harvard, he took high-level classes in philosophy and religion even during his first semester as a freshman.

Partially because his scholarship money was limited, Monroe said West took multiple additional classes each semester to graduate early in addition to working as a dishwasher and mailman while living in Leverett House.

“I think he took seven or eight classes in one year,” Monroe said. “We didn’t ever know that he was taking that big a load. And he still went to parties. He still hung out with us. And he got all A’s.” After three years, in 1973, West graduated from Harvard a year early — at just 19. Just four years later, he was an assistant professor at Union Theological Seminary.

After UTS, West subsequently held a professorship at Princeton University before arriving at Harvard in 1994. Just four years later, he would be appointed a University Professor — the highest degree of distinction for faculty. In 2002, after a dispute with then-President Lawrence H. Summers, West would leave Cambridge, before returning again from 2017 to 2021. He would then leave again, this time after Harvard’s decision to deny him tenure.

He has also become an extremely prominent political activist, advising top political candidates and speaking out on issues of race, foreign policy, and domestic issues. He has published 20 books, produced music with Prince, and made guest appearances in two “Matrix” movies. But despite his elevated public profile as an activist— West is currently running in the 2024 U.S. presidential race as an independent — he maintains that academia was always at the center of his life’s mission.

“I took ‘Veritas’ very seriously,” West said in an interview with The Crimson. “It’s always a very fallible, painful, and joyful quest all at the same time.” With polling numbers at or below two percent and plans to “abolish poverty” and “dismantle the U.S. empire”, he is more concerned with fighting a philosophical battle than the presidency itself.

“We’ve got to somehow get beyond hatred and revenge and talk seriously about truth and justice,” West said.

“We have to bear witness to that in highly visible places, including running for president,” he added.

‘Having the Time of My Life’ West’s professional career panned out as he planned it at seventeen.

“I was having the time of my life freshman year knowing that I was going to be a professor one day,” West said. Originally from Tusla, Oklahoma, West grew up in Sacramento, the heart of the Black Panther Party during the 1960s. When he came to Harvard, he maintained close ties to local Party organizing but was committed to his classes and his plan to graduate early. Along with volunteering with the Black Panther Party’s school breakfast program in Jamaica Plain, West was on Dorm

Crew, where he cleaned the Wigglesworth dorm bathrooms and juggled his intense course load that was preparing him for a career in higher education.

Fifty-four years later, West can still name half a dozen professors from his college years at Harvard who convinced him to pursue academia — a list that includes notable professors like John Rawls and Martin Kilson, the first Black professor tenured at Harvard.

Former Harvard professor Preston N. Williams still remembers West as an “extremely bright student” in his class on Christian ethics at the Harvard Divinity School.

“Cornel suggests that I am the person who suggested that he go into academics and get a doctorate,” Williams said. “That’s due to the fact that after taking my class, he wanted to write some papers on some matters dealing with Hegel, enlightenment, or understanding of God during that particular period.”

“He wanted to know if I would read them if he wrote them,” he

said. “So he wrote the papers, I read them, and I told him he ought to consider going into the academic profession.”

But even at college, West balanced academia and activism.

“I imagine that he early on came to the notion that he would do academics but he would also be an activist. He was always oriented in that direction from the beginning,” Williams said.

As an undergraduate, West was co-president of a Black student group and was one of two dozen Black students that occupied Massachusetts Hall for a week in 1972 to protest Harvard’ decision not to divest from oil companies aiding Portugal during the Angolan War of Independence.

“We had 3,000 people marching that weekend,” West said. “I had to get out of the office, take my Hebrew exam, and then get back in there again.”

‘Build on the Past’

While West said Harvard has

been “a profound blessing” in his life, he has been an outspoken critic of the institution for the last five decades.

When West resigned in 2021, he wrote that the “shadow of Jim Crow” was cast over the University, writing that his resignation was the result of a “cowardly deference to the anti-Palestinian prejudices of the Harvard administration.”

West’s attendance at pro-Palestine protests and encampments around the country in recent months have made him especially popular among young voters who overwhelmingly disapprove of U.S. President Joe Biden’s handling of the conflict.

In early April, West, a former faculty advisor to activist groups, took a break from his campaign trail to speak at a pro-Palestine rally outside Harvard’s gates.

“Harvard University, like any other institution in the American empire, is shot through with commodification, is shot through with corporatization,

is shot through with marketization,” West said. “It has legacies of white supremacy, male supremacy shot through it too.”

“We will be countervailing forces against it,” he added. He said there are certainly similarities between protests in the 1970s and 2024, but that younger activists should not let the model of the past constrain them.

“You can’t emulate and imitate the past,” West said. “You’ve got to build on the past and find your own voices and styles and do it in your own way.” West said he was encouraged by watching the current pro-Palestine student groups protest for divestment.

“I’m always encouraged by any group that’s standing up for justice, including the young brothers and sisters of all colors at Harvard in the last few months and years,” West said.

“There is no doubt that the genocide in Gaza is a pivotal moment,’’ he added. “We find out what the moral conscience of the American empire really looks like.”

‘It’s Your Fault’

But when asked why decided to run for president, his answer has nothing to do with the presidency. “What it really comes down to is I am a small part of a great tradition of Black people who have been so thoroughly hated but produce love warriors every generation, not just hate back,” West said.

His campaign, though, has angered many Democrats over fears that he will draw a meaningful number of votes away from Biden come November. West said he owes Biden nothing.

“You can’t just make a weak case and say, ‘Well, Brother West is making a stronger case so people are attracted to West but he’s stealing my votes,’” West said.

“No, you’re making a weak case, brother,” he added. “It’s your fault.”

THE NEWS OF THE renewed outbreak of war in the Middle East must be greeted with sorrow. The loss of lives and resources and of funds that could be allocated to help people instead of destroy them is regrettable no matter how just the cause or how great the provocation.

It would be easy to blame Egypt and Syria for resuming the bloodshed. All neutral reports indicate that the Eygptians and Syrians initiated the new hostilities in the Middle East. But to place the blame for renewed fighting squarely with one side or the other would be beside the point and would ignore the complexities of an inherently tragic situation.

While informal negotiations regarding the occupied territories have remained deadlocked, the Israelis have excited Arab anger by acting as though they intend to hold onto the lands permanently. Before the war, Israeli settlement of the West Bank of the Jordan River and the Golan Heights was well underway, and movement of Israeli settlers into the Sinai had begun.

Meanwhile, Israeli leaders have continued to mouth expansionist sentiments. One of the most inflammatory spokesmen has been the popular Defense Minister, Moshe Dayan.

“Our fathers had reached the frontiers which were recognized in the 1948 partition plan,” Dayan said in 1969. “Now the Six-Day Generation

has managed to reach Suez, Jordan and the Golan Heights. This is not the end. After the present cease-fire lines, there will be new ones. They will extend beyond Jordan--perhaps to Lebanon and perhaps to central Syria as well.”

Actions since 1969 have substantiated Dayan’s statement. Israeli oil rigs have stepped up exploration in the Sinai. Construction of tourist resorts has begun. As Dayan put it in 1971, “Other countries end their wars with the idea of going back to the points they started from. In our case, we want something new, new borders, new relations, a new state.”

With statements and conditions like these, it is not surprising that the Arab governments would feel pushed to recapture the occupied territories after six years of stalemate at the bargaining table.

Both the Arabs and the Israelis have lived a history of oppression--the Arabs through the brutalizing effects of European colonialism; the Israelis, through centuries of vicious bigotry which culminated in Nazi genocide. The history of each group forged in its members a special pride along with a fragile sensitivity against being trespassed upon.

Historical coincidence has thrown these two groups together on the same tract of land, limited both in size and in resources. The Arabs, especially the Palestinians, could only see the Israelis in 1948 as foreign intruders. The influx of outsiders promised by the creation of the state of Israel meant that Palestinians would be displaced

THE NIXON REGIME abandoned its last tattered claim to legitimacy Saturday night. By purging the Justice Department, which had refused to halt its search for evidence against him, Nixon conclusively demonstrated his contempt for the legal process and the AMerican people. His behavior has left Congress no option but to begin impeachment speedily.

Nixon has insisted all along on a separation of powers, but he has acted as though no power other than his own exists. His refusal either to comply with an appeals court decision against him or to bring his case to the Supreme Court blatantly violates the constitutional doctrine of checks and balances. When two members of his own branch of government, Special Prosecutor Archibald

WCox and Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus, refused to buckle under Nixon’s orders, he immediately fired them. His proposal to allow one senator friendly to the administration to hear the tapes was a desperate attempt at a last-minute face-saving compromise.

Nixon has been less concerned for the separation of powers than with keeping evidence away from investigators charged with powers of prosecution. He is interested not in confidentiality, but in immunity.

The departure of the attorney general, special prosecutor, and deputy attorney general must destroy any residual trust the American people might have retained in Nixon’s government. The public has seen Nixon pre-empt power not his own through a host of major and minor legal violations—from shielding secret campaign contributors to employing Thai mercenaries in Laos,

and a new, foreign polity introduced just at a time when nationalism was awakening in the Third World. As the Arabs were trying to expel the last elements of European colonialism, the Israelis--a new group whose external appearance and way of life seemed largely European--intruded. It is not surprising that the Arabs reacted with hostility.

Equally unsurprising was the Israelis’ militant response. A dispersed people--including many refugees from Nazi oppression--who had come together from all over the world to establish a homeland was forced to struggle against a new threat to its existence.

AFTER 25 years, even the most intransigent Arab leader accepts that the Israeli people are in the Middle East to stay. In the current conflict, for example, there have been no Arab calls to push Israel into the sea.

Yet this softening of rhetoric is no indication that the Arabs have accepted Israel’s right to exist as a nation. The right is a real one, it must be guaranteed; the Arabs must accept it. Their failure to do so will continue to harden Israel’s position.

One of the more unfortunate consequences of the continuation of hostilities in the Middle East is the blocked growth of progressive elements both in the Arab countries and in Israel. Feudal Arab governments like Jordan and Egypt have diverted their people’s attention from social reforms needed at home by sounding clarion calls against Israeli expansion. And Israel, once envisioned as a progressive, pioneering experiment, has sacri -

ficed some of its dreams to support a war economy. Peace will boost the chances that the thorniest Middle Eastern question--the grievances of the displaced Palestinian people--can start to be resolved. The Palestinians are a people with no country. Only in a peaceful Middle East, with an Israel confident of the long-term stability of its situation, can the Palestinians hope for the fundamental concessions which Israel must offer if an even partially Arab Palestine is to become a reality. The United States and the Soviet Union can play a constructive role in improving the situation in the Middle East by staying out. The two superpowers must lead an embargo on the sale and shipment of arms to/all potential Middle East combatants. Only then can the Israelis and Arabs resolve their differences through discussion rather than continuing to kill each other without settling anything. Before anything else can happen, the present war must stop, with a cease-fire established in place. Then the combatants can begin to talk--directly, with each other--about reducing the tensions that have brought wars. The Israelis must recognize that the Arab nations, particularly the Palestinians, have legitimate grievances and fears, and Israel should work to resolve those greviances and reduce the causes of those fears. Similarly the Arabs must recognize the sovereignty of Israel and that country’s need for security.

from impounding cnogressional funds to using wiretaps and burglary against political enemies. This, even without considering five years of outright deception in the handling of foreign policy, particularly on Vietnam.

NIXON MUST BE attacked on three fronts.

First, Congress should immediately begin impeachment proceedings against him. By terminating the Justice Department’s action, Nixon has made impeachment the only way in which his role in the Watergate affair can be investigated. No federal appointment—including that of vice president-designate Gerald Ford or of any designated attorney general—should be approved.

Second, the appeals court should take measures to obtain compliance with its order. Nixon’s attempt to work a compromise with Congress over the release of the Watergate tapes is an affront to the judiciary’s constitutional responsibilities and

power. Throughout the Watergate scandal the behavior of Judge John Sirica has symbolized the independence and honesty of American courts. This independent honesty should be again demonstrated by immediately citing Nixon for contempt. Finally, the American public must prove its will. Organizing petitions and persuading Congressmen to support impeachment proceedings would be crucial first steps. The public must demonstrate its belief that no government under Nixon can rule in its behalf legitimately or effectively. There must be a movement founded on the broadest popular base. The important task is to remove Nixon from office and to guarantee that no president can ever again effectively indulge in such gross violations of law and public trust. Nixon cannot safely be permitted to remain as president. He must be toppled.

E HAVE CALLED for Nixon’s impeachment in the past, for reasons which we continue to believe are even more important than his insistence that no independent person can legitimately investigate his administration’s apparent crimes. But the firings of Cox and Ruckelshaus, and Richardson’s resignation mean that for the first time impeachment may be a political possibility. It is therefore of crucial importance that people apply pressure to Congress, whose evident fear of any bold act seems to be the chief obstacle to impeachment.

People who share our belief that Nixon should have been impeached years ago because his conduct of the INdochina war was unconstitutional, repressive, and murderous, should write to their representatives to call for impeachment.

People who share our belief that Nixon should have been impeached months ago because of his assaults on civil liberties and democratic procedures—the Huston plan for burglaries and illegal wiretappings, the burglary of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office, the apparent attempt to influence the judge in the Ellsberg case, his lies to Congress and the American people about the bombing of Cambodia—people who detested these actions should write to their representatives to call for impeachment. And people who have opposed impeachment in the past, but who don’t think Nixon can act simultaneously as investigator, judge, jury, prosecuting attorney, court of appeals, and defendant—these people, too, should write to their representatives to call for impeachment. By emasculating the Justice Department and refusing to obey the courts, Nixon has left these people with no recourse other than through their elected representatives in Congress.

–With these editorials, The Crimson joins the seven other Ivy League newspapers in calling for the impeachment of President Nixon. The Brown Daily Herald, The Columbia Daily Spectator, The Cornell Daily Sun, The Dartmouth, The Daily Pennsylvanian, The Daily Princetonian and the Yale Daily News have issued similar positions in the aftermath of the departures of Cox, Richardson and Ruckelshaus.

vard and other universities ensure that male and female athletes have “equal access” to sports and “equal facilities.”

BY THOMASIn 2024, it’s easy to look at the relative equality between men’s and women’s sports and assume that it has been this way forever. But 50 years ago, that was anything but the case. In 1974, Harvard University and Radcliffe College were entirely separate academic institutions, but their athletics departments

– in what was a test-drive for the eventual union of the two schools – made the historic decision to formally merge, finalizing the union first proposed in 1971. However, even after the official conjunction of programs and financial budgets, women’s teams were still viewed as secondary to their male counterparts. For the Harvard Athletics Department, the merger caused financial stress, as it suddenly had to account for Radcliffe’s 11 varsity teams in addition to its existing 19 men’s teams. Meanwhile, for the female athletes and Radcliffe athletics administrators, the union with Harvard provided them with a larger budget for equipment, coaches’ salaries, transportation, and facilities. Tension arose within the newly unified program, as administrators had to suddenly allocate funds that would have once been given to men’s teams to instead enhance Radcliffe’s sports teams.

Roanne Costin ’74, a dual-sport athlete, was a member of the first Radcliffe crew team and a varsity swimmer. Costin explained in a 1999 interview that the “budget was where the power was,” and “just the idea of leveling the playing field” was a major step forward for female student-athletes.

The merger of the two departments was aided by the passing, in 1972, of Title IX, a federal statute which legally required that Har-

“Without the force of the law behind us, it’s doubtful that the university administrators at Harvard or elsewhere would have seen the importance of equal resources for women athletes,” former Radcliffe tennis team captain Lissa Muscatine ’76 said. “Title IX was the wind at our backs.” Muscatine attributes much of the progress that has been made for gender equality in athletics to Title IX. Unfortunately, at the time of the merger and the passing of the monumental legislation, Harvard did not have adequate facilities for both sexes’ varsity, JV, freshman, and intramural teams, all of which held consistent practices. The University only had one regulation-size basketball court, swimming pool, and set of squash courts, making these sports particularly challenging to schedule.

Therefore, immediately after the merger in 1974, the Radcliffe sports teams were considered to be the athletic department’s lowest priority. If a court scheduling conflict arose between male intramurals and a women’s varsity team, the men were allowed to continue practicing as the women were escorted off the court. That being said, the merger affected Radcliffe’s teams very differently. Some teams, such as crew, sailing, and skiing, benefited greatly from the unification. These three female teams did not require limited practice space, and could enjoy the increase in their budgets, which went from $75,000 in the 1972-93 season to $144,350 after the merger. However, other teams, including Radcliffe basketball, tennis, and swim, struggled to earn equal access to Harvard’s facilities.

For instance, the women’s basketball team only had one hour of practice time per week on the regulation-size court. It practiced six times a week for two hours in the Radcliffe gym, which was at least 15 feet narrower than the regulation court. Meanwhile, all of the men’s teams, including intramural, practiced on the regulation

court daily. The women’s swim team also struggled with the practice schedule, as it was only given four-and-a-half hours per week in the regulation-size pool. Additionally, the lanes it was allocated were often located under the diving board, and its practice time would occur simultaneously with the men’s diving practice. In comparison, the men were given four hours of practice time in the pool per day.

Eventually, the men’s swim coach decided to give the women at least an hour per day to practice in the pool, but practice scheduling remained the subject of fierce debate during the post-merger period. The bargaining process between the men’s and women’s teams was also made more difficult by the antagonistic stance of

women’s program unless there is perception of this,” she added. Paget’s demand for more administrative buy-in for the merger fell on deaf ears. Despite being instructed by university administrators to look for a path toward gender equality in athletics, Watson dug in deeper and prepared for battle. In an office memo, Watson made his fierce opposition to the merger abundantly clear.

“Are we justified in dismantling established men’s programs that have operated in a competitive atmosphere in order to accord equal treatment to programs which are not really equal in either intensity or dedication?” Watson asked. “[For] at least several Radcliffe teams, being a member of the varsity is more a matter of interest than ability.”

competition,” she said. “This only began to change toward the end of my undergraduate career and it took more years to reach anything close to parity.”

The Women’s tennis team had to work out an agreement with the men’s Head Coach, Jack Barnaby, to use two courts during the indoor season. Other teams, including swimming, and basketball, followed suit.

In 1975, Muscatine identified this injustice in a Crimson profile, stating “I think the Radcliffe athletic department isn’t really ready for varsity sports.”

In that profile, written when Muscatine was a junior at Radcliffe, she said, “I’m not like Roanne Costin or Connie Cervilla,” referring to the women who started the fight for equal athletic opportunities and access at Harvard earlier in that decade. “Robert Watson, he has to listen to me. It’s not like before.”

Cervilla ’74 was the proud captain of the Radcliffe heavyweight crew team. For the Radcliffe crew teams, the inequality they faced made them reject the idea of complete assimilation into Harvard Athletics.

“To have such a special year on the 50th anniversary of Harvard Women’s tennis was icing on the cake,” Green recalled. “It was such an amazing feeling to be supported by everyone. To showcase what our team, culture, and fighting spirit is all about is a tribute to those that came before us,” Green added.

Muscatine had a similar takeaway. “Watching the current team play was a joy. They are so good and they were all such great examples of women competing in sports at the highest levels while also pursuing serious academic goals,” she said. “I’m sure there are still areas where progress lags, but there’s no doubt that the situation for women athletes today has far improved over fifty years ago. It gave me great pride that Harvard finally has a woman [Director of Athletics] and Coach Green is an icon herself!” She was disappointed to see the gradual erasure over time of the Radcliffe name from

Robert Blake Watson, Harvard’s Athletic Director at the time, toward greater integration.

During the merger, Watson intended to replace 11 Radcliffe athletics administrators and only make a single addition to the Harvard staff. Mary Paget, the sole remaining Radcliffe athletics administrator, had been the Director of Radcliffe Sports for 12 years, and was forced into a position ranked lower than the Harvard Athletic Department’s ticket manager.

In the frequent, antagonist chain of memos exchanged between Paget and Watson from the time of the merger, Paget wrote that it was “impossible to add 11 women’s varsities to the 19 men’s varsities without adequate supportive services.” “I anticipate immobilization and attrition of the

Despite their lack of equal facilities, the women’s crew, swim, and tennis teams all had perfect seasons in 1974. Prior to its merger with Harvard, five of the 11 Radcliffe teams already boasted national or regional titles.

Eventually, Watson relented, allowing Radcliffe’s varsity teams to take priority over men’s intramurals for the 1974-75 season.

1974 also saw the founding of the Radcliffe tennis team. Muscatine immediately noticed the discrepancy between the way her team was treated and the men’s team.

“Even with Title IX we still had second-tier resources. We often didn’t get equal court times for practices and we didn’t have a professional coaching staff, comparable uniforms and equipment, or adequate funding for travel and