THE HARVARD CRIMSON

GUINEA PIGS. The Class of 1999 became the first group of students at Harvard who were randomly assigned to Harvard dormitories, a break from the previous process which allowed students to rank their preferred Houses. The randomization of Harvard’s undergraduate housing was initially met with disapproval from students and faculty alike, but others believed that the tendency of students to self select into certain Houses required administrators to change the process. SEE PAGE 6

Radcliffe College was struggling. For years, the venerable counterpart to Harvard had been in dire financial straits, was forced to dramatically restructure itself in 1996, and had recently been shedding top administrators and staff. The situation was gloomy enough that in April 1998, the Boston Globe predicted that Radcliffe College would soon be no more. Within a year, they would be proven right.

After a year’s worth of secret, closed-door meetings — whose secrecy often troubled Radcliffe affiliates — Harvard and Radcliffe announced that they would be officially merging in April 1999. By the end of the calendar year, Radcliffe College would cease to exist.

It was a deeply historic announcement, the most major development in the history of the relationship between the two schools since the landmark 1977 “non-merger merger,” when Radcliffe students enrolled as official Harvard College students. Still, for some, the loss —

though symbolic — was still deeply saddening.

“When I lost Radcliffe, I lost a place that was an important counter space,” said Kathryn B. Clancy ’01, who led the Radcliffe Union of Students in 1999 and 2000. “If you think Harvard is sexist today, guess how sexist it was 25 years ago.” Lisa E. C. Vogt ’01-’02, who was the president of RUS after Clancy, wrote in an emailed statement that after Radcliffe was dissolved she felt a “vague sense of loss.”

“Radcliffe was the one place where female undergraduates were assumed to be the top priority (in theory, again it wasn’t much present in reality),” Vogt wrote. “After the merger I felt a loss of that institution that was fundamentally set up to support me as a woman at Harvard.”

“But it also meant that Harvard couldn’t pass the buck for any ways it was failing women,” she added.

‘The Best Way Out’

As Radcliffe struggled, top officials from both Harvard and Radcliffe convened starting in late 1998 to chart out the future of the institution. Then-Harvard

Tom Cotton’s Journey to the U.S. Congress

PAGE 9. Before Senator Tom B. Cotton ’99 became a rising start in the Republican Party, he prepared for a career in Congress as a student organizer of the Harvard Model Congress conference.

President Neil L. Rudenstine, along with members of the Harvard Corporation and the Radcliffe Board of Trustees, met several times to discuss Radcliffe’s next steps.

According to Rudenstine, who oversaw the merger, these financial concerns made an official merger attractive.

“No question that finances, I think, made the difference,” he said in an interview with The Crimson. “It got to a point where the program that they had hoped would be reviving Radcliffe turned out, just not working.”

There were two options: one, endorsed by alumni of Radcliffe, would rename Radcliffe College to the Radcliffe Center for the Advancement of Women and acknowledge Radcliffe as “the focal point on campus of programs on women.” The other would also include an Institute in Women’s and Gender Studies and a Program in Women’s and Gender Studies with five to seven new professorships.

The group would settle on a hybrid decision: a Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study that was designed to “sustain a commitment to the study of women,

SEE ‘MERGER’ PAGE 7

A President was getting impeached for the first time in 130 years, but Harvard students were more focused on finals.

“I haven’t been glued to it or anything,” Tad A. Fallows ’02 told The Crimson in January of 1999, just days after the Senate’s trial of President Bill Clinton began.

Indeed, as the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal — in which then-President Bill Clinton would first deny and then admit his affair with White House intern Monica Lewinsky — developed, some members of the Class of 1999 said that the news did not dramatically shape their time at Harvard.

Twenty-five years later, and in a much more polarized nation than that of 1999, students look back on the tawdry scandal that would engulf the White House.

‘Somewhat Frivolous’

When news of the scandal broke — first online in the Drudge Report, followed shortly after by The Washington Post — it caught

PAGE 11. The United States Senate admirably handled the trial of President Bill Clinton following the Monica Lewinsky affair, declining to convict the president on charges of perjury and obstruction of justice.

many on campus by surprise, and fascination.

“Initially, like the rest of the country, I think everyone was sort of surprised,” Rustin C. Silverstein ’99 said in an interview. “And curious, titillated by the revelations as they started to come out.”

Though much of the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal played out as undergraduates lived on campus during the spring and fall of 1998, many of those present recall it being a subject of interest — but one mostly relegated to the background.

“It was a prominent event in the background that people would talk about in certain circles, and would occasionally come up,” Lanhee J. Chen ’99 said. “I don’t recall it being all formative, in terms of our experiences.”

“It felt more like background noise,” he added.

Silverstein emphasized that the scandal, though of interest to some, did little to impact day-today life.

The scandal was viewed mostly as “tabloid interest,” he said.

“Somewhat frivolous.”

Chen said that while “there was a lot of awareness” for those

more politically aware, a lot of students turned the events into a punchline.

“We did these T-shirts every year for Harvard Model Congress for the conference,” Chen said. In 1999, “the T-shirt had some design on it, and there was a guy saying, ‘more fun than a deposition.’”

“To the extent there was discussion, it wasn’t particularly serious or heated discussion,” he added. “It was really sort of more poking fun at the entire situation.” But while many viewed the scandal from a distance, several Harvard undergraduates served as White House interns alongside Lewinsky herself. One Harvard College student, J. Caroline Self ’99, who worked in the White House from June to December 1996, was called to testify in front of a grand jury in February 1998 For some of those who worked alongside Lewinsky, such as Carlton F.W. Larson ’97, the scandal contained a personal element.

“It was so personal in a way,” Larson said. “It’s very, very strange to see someone you know caught up in something like this.”

“The initial feeling is just sort of complete disbelief,” he said.

8

David Malan’s Path From CS50 Student to Professor

PAGE 10 David J. Malan ’99 entered Harvard College as a Government concentrator. But one Computer Science course, CS50, changed his life and kept Malan on campus long after he graduated.

Sept. 16, 1998

FINANCIAL AID. Harvard raises undergraduate aid by 20 percent after setting aside another approximately 9 million dollars for financial aid. The changes are expected to impact over 3,100 students.

Sept. 4, 1998

Nov. 20, 1998

LIFTOFF. The first module of the International Space Station, the Russian-made Zarya, is launched from Kazakhstan.

Nov. 23, 1998

EPPS RETIRES. Archie C. Epps III, Harvard’s longtime Dean of Students, announces he will be retiring after 35 years at Harvard, 28 of which he served as dean.

Dec. 19, 1998

IMPEACHED. The House of Representatives impeaches President Bill Clinton, making him the first impeached president since Andrew Johnson in 1868.

Jan. 1, 1999

EURO ESTABLISHED. The Euro is established, unifying 11 of the European Union’s 15 countries under a single currency. Just online at first, physical coins and banknotes would come three years later.

Feb. 4, 1999

FEDERAL INVESTIGATION. The Crimson reports that the Department of Justice is investigating alleged insider trading and misuse of federal funds by two employees of the Harvard Institute for International Development.

Feb. 9, 1999

SUPREME COURT. The Navajo Nation’s Supreme Court holds a session in Harvard Law School, the first time the University has hosted a tribal court.

Feb. 12, 1999

ACQUITTED. The Senate acquits Bill Clinton on charges of obstruction of justice and perjury.

March 15, 1999

NEW LANDMARK. The Cambridge City Council unanimously votes to make the Swedenborg Chapel a historical landmark. The historic building across from William James Hall was under threat of demolition.

March 27, 1999

NATIONAL CHAMPIONS. After a successful season and a 30-game win streak, Harvard’s women’s ice hockey team wins the national championship, defeating the University of New Hampshire 6-5 in an overtime victory.

June 9, 1999

WAR ENDS. After 16 months of conflict — and eleven weeks after the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia began — Yugoslav forces agree to withdraw from Kosovo.

HEY, GOOGLE. Sergey Brin and Larry Page, Ph.D. students at Stanford, officially create Google, Inc., a new web search engine.

iot was preppy.

BY JOYCE E. KIM AND ANGELINA J. PARKER CRIMSON STAFF WRITERSFor more than two decades, Harvard students were able to rank where they wanted to live for three years of college. But in 1995, Harvard’s administration decided it was time for a change.

In a decision that would be met with fierce blowback, Dean of Harvard College L. Fred Jewett ’57 announced that effective with the Class of 1999, rising sophomores in blocking groups of up to 16 would be randomly assigned to one of Harvard’s 12 upperclassmen Houses — “without any pre-determined order or pattern.” Jennifer H. Wu ’99, who served on the House Committee for Pforzheimer House, said that her class was “kind of a guinea pig for the randomization.”

“When we were told as freshmen, I don’t think that we knew what it meant, and nor did anyone else, because it never happened before,” she said.

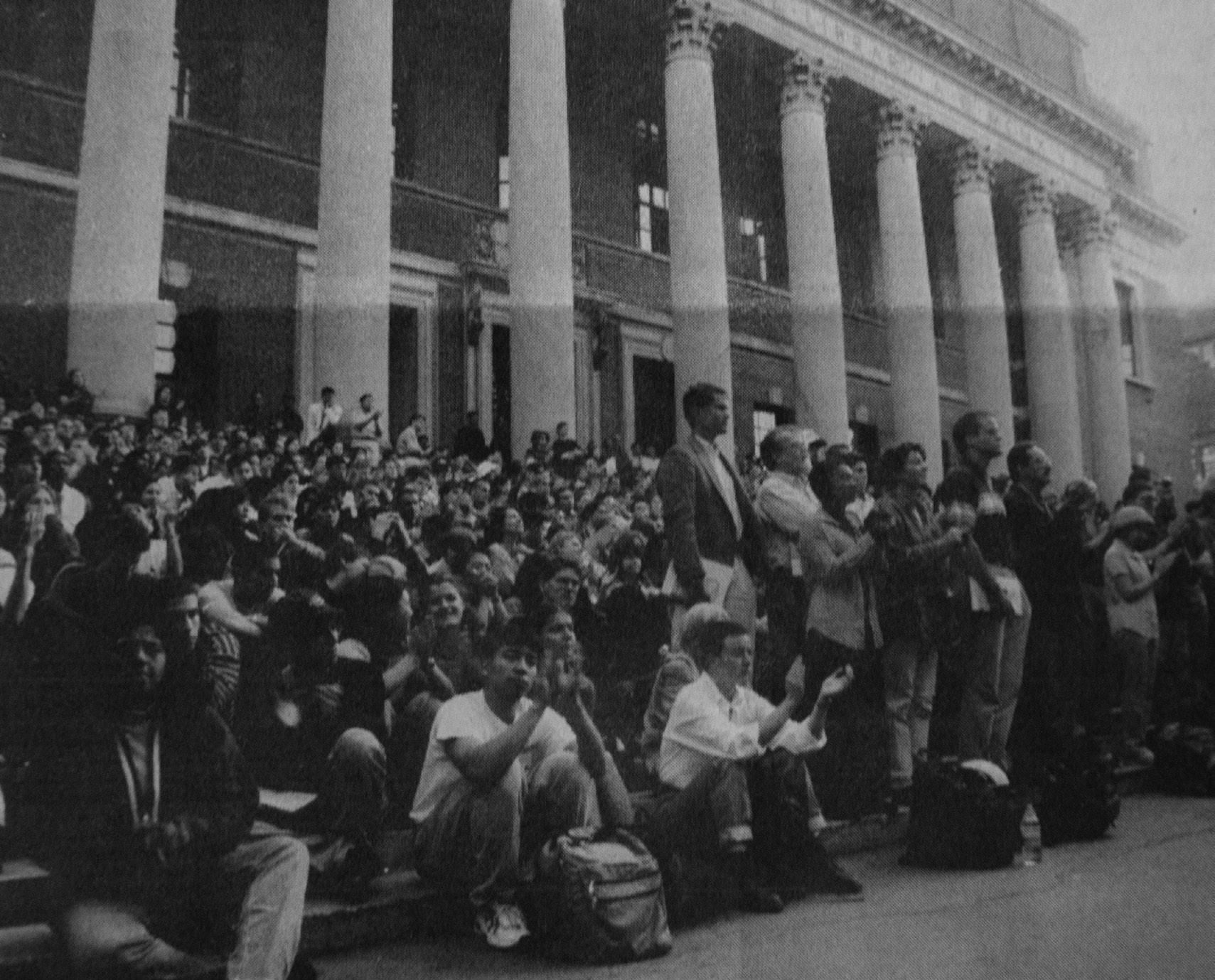

At the time, there was an uproar to the College’s decision. An Undergraduate Council poll at the time revealed that 82 percent of the student body opposed randomized housing, and shortly after the decision, more than 200 students and faculty members rallied outside of University Hall to protest the change, in what The Crimson called “the largest student-led protest in recent Harvard memory.”

But soon enough, students grew accustomed to the change — and the House system remains randomized to this day, though in 1999 the maximum size of a blocking group was shrunk to eight with the Class of 2003. 25 years later, students and faculty who lived through randomization look back at the process that radically changed what it’s like to live at Harvard.

‘Something Should Be Done’

The first Houses were first built in 1930, and were meant — according to then-Harvard President A. Lawrence Lowell, Class of 1877 — to be “be as nearly as possible a cross-section of the College.” In 1971, after decades of House faculty deans — then called masters — deciding who got to live in the House, students were allowed to start ranking their options. The system inadvertently produced stereotypes surrounding each of the Houses: Adams, for instance, was known to house artsy kids, the Quad was predominantly a space for Black students, and El-

“I had a lot of Black friends, and they were often in block groups and they wanted to be in the quad. They wanted to be kind of in that self-selected atmosphere, and that was something that was desirable,” said Rudd W. Coffey ’97.

The Houses’ reputations meant students would self-sort when it came time to rank, perpetuating the character each House was known for.

“Every House at that point — it had a unique kind of quality,” Wu said. “As freshmen, you automatically had ideas as to what the Houses’ character was because it wasn’t random. So there was a lot of pre-meds in certain houses and there was a lot of athletes in river Houses because it’s closer to the fields.”

But for some who were House masters at the time, the arguments against randomization — the loss of treasured House traditions, or spaces for minority students — were not as strong.

“Those did become places where African American students would feel comfortable, because it was with a lot of other students. I know the reasons that that was good, but I think given the rapidly changing demographics of Harvard, that was just not sustainable,” said Diana L. Eck, who was the Lowell House faculty dean in 1999, then known as the House “master.” “And that’s true for all stereotypes.” John E. Dowling ’57, who retired as master of Leverett House in 1998, said that despite people’s fears, treasured House traditions persisted after randomization.

“The arguments against randomization was all the traditions will be lost in the various houses — which over the years have grown to be important part of house life. That isn’t true,” Dowling said. “I think it’s worked very well,” he added.

Dowling said that in his view, a diverse House was crucial to the success of the House system.

“The point of the House system is that you learn as much from your fellow students, as you do from the faculty, and from what else goes on at Harvard. And therefore having people with different views, different expertise and foreign talents that you can learn from in a House, is what makes the House system very special,” he said.

Not all House Masters were in support of the change, though.

Adams House Master Robert J. Kiely fiercely opposed the College’s new policy, even addressing the crowd at the anti-randomization rally in the fall of 1995.

“The least diverse of our houses are more than 100 times as diverse as University Hall. Diversity is a relative matter,” Kiely said at the time. “So you wonder, who are they to tell you to be diverse?”

Still, the self-segregation did at times create issues — like when concerns arose that Kirkland House would be in violation of NCAA policies prohibiting athletic dorms, since “so many athletes now who had selected and were in Kirkland House,” according to Dowling. The stereotypes were so entrenched, Dowling said, that a student poll found that most students would not be comfortable living in a majority of the upperclassmen houses — a trend Dowling said was crucial in shaping his views in support of randomization.

“We couldn’t have almost little clubs in terms of individual houses,” he said. “So, that was really the thing that pushed me over the side saying, ‘Hey, we’ve got to do something about this.’ Some of the masters felt something should be done. I was one of them. Then, Dean Jewett felt that something should be done.”

‘It Came Out of Nowhere’

The administration viewed the homogeneity of the Houses as a serious problem, prompting a 1994 report by the Committee on the Structure of Harvard College that found that “pronounced variations in the populations of

of ‘Hey, let’s all talk about this and decide if there are good reasons to change the system,’” Coffey added.

The decision, Coffey said, “took the students by shock.”

Despite the recommendation to control for gender, Wu, who was one of three women in her blocking group of 16, said that in her year, there were multiple allmale blocking groups that were sorted into Pforzheimer House, making the House approximately “80 percent men or more,” though she added she remembers her time there fondly.

“It was probably like real life in Corporate America,” she said.“I had never experienced that kind of gender imbalance in my living circumstances in my entire life.”

Sarah J. Cooper ’97, a former Crimson Editorial Chair and Currier resident who was in the minority of students not in a house she ranked, said the decision to randomize housing mattered to undergraduates because it meant their experience wouldn’t necessarily be “what they thought it would be”

“When you have something in place that gives people more control over their future — their future three years at a college or at Harvard — that feels like it is being taken away, I think people

It came out of nowhere. No one was expecting it. It hadn’t been something

the various Houses” could result in students being “educationally deprived.”

To fix that, the committee — chaired by Jewett’s eventual successor and computer science professor Harry R. Lewis ’68, recommended that the preference-based system “be abandoned in favor of random assignment of roommate groups at the end of Freshman year,” but that there be “controls on gender ratios enforced as at present.”

Some, though, said that the decision was made with little transparency.

“It came out of nowhere,” said Coffey, who served on faculty committees and was a “very senior member” of the Undergraduate Council, Harvard’s former student government.“No one was expecting it. It hadn’t been something discussed.”

“This was this thing that hadn’t been discussed, debated, gone through what I would consider the appropriate channels

worry about whether their college experience will be the same as they envisioned it,” she said.

“I think a lot of people had an image of themselves, walking through the square or walking toward the river, going into their dorm, their house, and so for some people, that wouldn’t happen,” Cooper added.

But for others, the abrupt change triggered a wave of discontentment.

Though the College’s goal was to increase the diversity in the Houses through randomization, many at the time argued over the definition of “diversity” and some argued that the College’s move was misguided and robbed minority students of spaces they could be comfortable in.

E. Michelle Drake ’97, the then-president of the Civil Liberties Union of Harvard, told The Crimson in 1995 that she didn’t “like the University’s moving them into the community so people can get exposed to them and

see what it’s like to live next door to a Black person.”

Irene C. Cheng ’97, the then-president of the Asian-American Students Association, told The Crimson at the time that for students of color who “feel uncomfortable in the presence of these old-boy networks, final clubs, things like that,” a solution “is to form communities of people who are supportive.”

Even Kiely — the Adams House master who opposed randomization — said then that “enforced diversity looks good on paper, but it doesn’t work best in social terms.”

Looking back, Wu said that when randomization was instituted it seemed like “Harvard was focused on facial diversity, rather than substantive diversity.”

“My belief, now looking back, is that one of the reasons that people perceived a lack of diversity is they saw a lack of racial diversity. So for example, Quincy house was known for having all the Asians and being pre-med,” she said.

Randomization, Wu said, “focused on what it looked like, and not what it was.”

‘Better Off’

Still, for many, randomization seemed like the right choice — a sentiment validated by the persistence of the system.

Lewis, the former College Dean whose committee recommended randomization, said he believed the original concerns surrounding the shift to randomization — namely, that students from minority groups would lose their affinity spaces — were “overblown” because “none of the disasters that were predicted seem to have occurred.”

“I don’t want to belittle the problems that are confronted by minority student groups, be they any of the ones that I’ve discussed — the Black students or the gay students, for example, who do have a different Harvard experience,” he said. “But I’m not persuaded that they have wound up worse off because they are no longer as socially, as residentially segregated as they once were.”

“I think that they — as well as Harvard as a whole — are better off that the housing system is integrated now,” Lewis added.

Today, many argue that randomization has been beneficial for the House system.

Cooper, the former Crimson editorial chair, said she ultimately thought randomization was “a much better way to run things” because the rank-based system didn’t guarantee students would receive their preferred housing placement, and “there were always people who didn’t get any of their choices.”

Despite her disappointment at

being randomly assigned to live in Currier, Cooper noted that she met her husband in Currier, and that she has “memories there, memories of my roommates and my friends and people I met.”

“I think that’s really what makes your house your home for three years,” she added. Wu said that generally, “randomization makes sense” because it opened up opportunities for upperclassmen to forge friendships based on proximity, rather than past interactions.

“It takes people out of what they’re used to,” she said. “Randomization causes you or allows you or forces you to hang out with people who maybe you didn’t know freshman year, and it turns out that many of those friends that you meet as sophomores, juniors, and seniors turn out to be your best friends.” Eck noted that despite initial protest over the switch to randomized housing, the student consensus on the decision soon changed to acceptance.

“The pushback against randomization may have gone on for a little bit, maybe a year or something as people got used to it. But you know, frankly, we didn’t ever hear anything about it after that,” Eck said, adding that House traditions — like Adams House’s drag nights and queer-friendly culture — persisted.

“But it wasn’t as if you were not going to feel great if you were gay or lesbian or trans and ended up in Currier,” she added. For Eck, the former Lowell House faculty dean, houses should strive to be welcoming environments for all types of students rather than a magnet for just a select few — something randomization was able to accomplish.

“All of the Houses should be places that feel welcoming, and a home for Black students, gay students, first-gen students,” she said.

“Frankly, I didn’t think twice about randomization being a good idea. I just assumed it was and it was exactly that kind of community that I wanted to be involved with, because it was so very diverse,” she added.

joyce.kim@thecrimson.com angelina.parker@thecrimson.com

she ought to look out, because he might work hard enough to end up in a class with her.

BY TILLY R. ROBINSON CRIMSON STAFF WRITEROn Sep. 18, 1998, South African President Nelson Mandela stood in front of an array of University officials and red-robed scholars — including then-Harvard

President Neil L. Rudenstine — and awed a packed crowd of 25,000 in Tercentenary Theatre.

The scene resembled a Harvard Commencement ceremony. The lawn between Widener Library and Memorial Church was decked out in the banners of Harvard’s twelve houses and its graduate schools.

“Everybody was racing — 21-year-olds running like elementary-school kids at recess,” Mark E. McIntosh ’99 told Harvard Magazine at the time.

The event was a specially-convened “convocation” to award Mandela an honorary doctorate of law.

Mandela had in fact been asked to speak at Harvard before — The Crimson reported he had been invited each year since his election as president in 1994 — but he had declined the invitations because of his duties in South Africa.

When Mandela visited the United States in September 1998, Harvard managed to squeeze the ceremony into a narrow three-hour window in his schedule.

Alicia E. Plerhoples ’01, who attended the speech as a sophomore, recalled it as a “surreal” experience.

“I remember going down with my friends to watch it and just thinking, ‘This is incredible that we are getting to hear directly from President Nelson Mandela,’” she said. “Everybody was really listening to every word, hanging on every word he was saying.”

She said she has kept a commemorative VHS tape of Mandela’s speech, although she doesn’t have a cassette player to watch it.

Mandela began his speech with a pair of stories. In one, he recounted dialing an establishment in South Africa. The woman on the other end of the line refused to tell him her name until he told her his. The woman, Mandela said, “became very cross” and asked him “Have you passed your matric?” — referring to South Africa’s university entrance exam — to which Mandela said that if passing the exam was the qualification to talk to her,

“‘She said, ‘You will never be in my class,’ and banged the telephone,” Mandela said. He paused before adding, “How I wish she were here today,” as the crowd roared.

But Mandela, in his speech, said he was not accepting his degree as a mark of individual accomplishment. Instead, he said, he chose to see it as a “tribute to the struggles and achievements of the South African people as a whole.

For Mandela — who led South Africa after spending 27 years in prison for his struggles against apartheid — the speech was as much a call to action as a reflection on the past.

“The world is still beset by great disparities between the rich and the poor, both within countries and between different parts of the world,” Mandela said.

He praised democratization efforts across the globe, but he warned his audience that “the freedoms which democracy brings will remain empty shells if they are not accompanied by real and tangible improvements in the material lives of the millions of ordinary citizens of those countries.”

But while thousands celebrated his arrival, Mandela’s speech followed more than a decade of intense anti-apartheid protest at the University, including the construction of a shantytown in Harvard Yard — something not lost on alumni, who argued that Harvard was cashing in on Mandela’s celebrity despite its opposition to divestment.

In a Nov. 30, 1998, letter to the editor of The Crimson, five Harvard alumni accused the University of “jumping on the bandwagon of Mandela’s worldwide fame and political success.” The letter noted that Harvard had rebuffed calls for divestment for years.

“Harvard needs to apologize to the people of South Africa, as well as to generations of students and alums who tried to get the University to do the right thing at a time when it could have influenced events,” the authors wrote.

The Harvard Gazette’s frontpage story on the ceremony never mentioned the fight for divestment, the letter claimed. Nor, for that matter, did Mandela.

The ceremony also featured the announcement of the Emerging Africa Project at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Center for International Development, which Mandela de-

scribed as “timely and greatly welcomed” and noted the program’s plans for collaboration with African scholars

Economist Jeffrey D. Sachs ’76 — the then-CID director — announced the project’s creation alongside professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. and former Ghanaian finance minister Kwesi Botchwey, who helped spearhead the program. Sachs wrote in an email that he was “profoundly grateful and honored” that Mandela agreed to help inaugurate the program.

When he was done speaking, though, Mandela did not rush out of the Yard, instead mingling with the audience.

He hugged students and shook their hands, thanked each member of the Harvard University Choir, and met each student who performed the South African national anthem with the Harvard-Radcliffe Kuumba Singers.

“It was a glorious day,” Sachs wrote. “I was delighted that so many people in the Harvard community were able to celebrate this very great man.”

tilly.robinson@thecrimson.com

gender, and society.” The “particulars,” Rudenstine said, would be figured out by the newly-formed Institute’s dean.

Rudenstine said that as the board deliberated, he was particularly focused on the scope and distinctiveness of whatever would come about as a result of the merger.

“Having a much broader institute that would be open to many subjects and many people, but with an emphasis in part on women, seemed to be the best way out,” he said.

‘Tremendous Sense of Bereavement’

The April announcement, though, was met with mixed reactions.

While many students at the time were indifferent to the official merger — the student experience had functionally been the same for decades — Radcliffe alumni had stronger reactions because of “nostalgia,” according to former Harvard President Drew G. Faust, who would be appointed the Institute’s first dean in 2001.

cused programming, but would be turned into cubicles after the merger.

“In addition to the fact that we had events in that space, that also was just a space that like when people wanted to get away from frankly, men, we went and hung out there,” Clancy said. “All of that we lost, and without any particular say in how any of that happened.”

Twenty-five years later, some Radcliffe alumni continue to hold that grudge. They believe they have never regained the authority they once had over their alma mater, alleging that Harvard has led the Institute astray.

“Radcliffe Institute isn’t even related to issues of gender, or feminism anymore — at all,” Clancy said. “It’s an ahistorical place where Harvard has figured out how to do some stuff with very little grounding in what it used to mean to those of us who were more close-

“I had to reach out to them and try to calm them down and make them believe in the new Institute and not feel this tremendous sense of bereavement that was really widespread and deeply felt by many of the alums,” Faust said. The alumni held a particular mistrust for Harvard because many believed they had been deliberately excluded from conversations about the merger. A year before the official merger, Margaret

“There were a lot of extremely upset Radcliffe alums who felt their college had been taken away from them and big bad Harvard was going to oppress Radcliffe,” she said. By 1999, Radcliffe alumni had donated more than $72 million to Radcliffe College — donations that the merger threatened. Radcliffe alumni grew increasingly suspicious of Harvard, believing the University would mismanage their donations and underprioritize the Institute. Faust said she had to work quickly and actively to win over these alums.

M. McIntosh ’56 had resigned from her role as the Second Vice President of the Radcliffe College Alumnae Association in protest at the secrecy of top-level discussions.

Cecily C. Selby ’46, a former member of the Radcliffe Board of Trustees, told The Crimson on the day of the merger that “none of us seem to understand why secrecy was essential.”

“I’ll always be loyal, but it’ll be far easier to be loyal now that there are no secrets,” Selby added.

‘They Were Taking the Money’ The students at the time, though,

were less preoccupied with the state of the merger and more concerned with the terms, according to Clancy, the RUS co-president.

Clancy said that prior to the merger, RUS maintained an endowment funded by mandatory $5 dues from students. However, RUS lost access to these funds after the merger.

“They basically met with us and told us they were taking the money,” she said. “They were like ‘when this merger happens, since there will no longer be Radcliffe students, this money, these dues that you’ve been accumulating, that’s a pretty good amount of money, so

we’re going to use it for different purposes now’ and they just took it.”

“This was a moment where we were treated like little babies who didn’t know how to handle our own money,” she added. “And we were going to get our money taken away and we had absolutely no recourse to do anything about it.”

Clancy said some students were also particularly concerned about the merger’s effects on communal spaces designed for Radcliffe College students, like the recently-established Lyman Common Room in Agassiz House — a space that often hosted female-fo-

ON THE HORIZON. When members of the Class of 1999 graduated, the new millenium was quickly approaching.

BY ARAN SONNAD-JOSHInly months out of col-

Olege, the Class of 1999 had just begun their new lives post-Harvard when the world entered the new millennium.

“Everybody, when they graduate from college, thinks of that as being the most important thing in the entire world — that you’re graduating and you’re launching out into the universe,” said Chana S. Zimmerman ’99, a former Crimson news editor. “The fact that the turn of the millennium

was gonna be the following year, we thought that was our due.”

“It just seemed normal because, all of our lives, we had known that we would graduate in 1999,” she added, noting that their official class song was Prince’s “Party Like It’s 1999.”

While members of the Class of 1999 say that nervousness over Y2K — the global panic over expected computer errors once calendars rolled over to the new millennium — and excitement over a new millennium did not predominantly feature during their time at Harvard, their senior year and lives immediately afterward were shaped by trends that continue through today — including the introduction of modern-day technology. The Crimson would launch the first edition of its website in the fall of 1998.

“Freshman year, we used the Yahoo directory to navigate the web,” said Adam R. Kovacevich ’99. “Gradually, people started using Alta Vista as our first search engine, and then I think we became aware of Google, really, near the end of our time there.

Careers in tech companies, Zimmerman says, had just begun to take off as an option for the newly-minted graduates.

“It was one of those careers that your parents wouldn’t really understand what it was you were doing,” she said.

“By the time we graduated from school, the internet had taken over everything,” Zimmerman said. “You could buy things on the internet. We were well on our way to doing what you can do now — minus the smartphones — and it was a massive dislocation.”

In just four years, the Class of 1999 witnessed huge changes in the way that people interacted with the internet — including the introduction of e-mail, which rapidly spread after it arrived at Harvard in 1994, just one year before the Class of 1999.

“My first email was a Harvard email on a Pine server — like black screen, green text. I didn’t know anything about etiquette of email and that kind of communication using the web,” said Nicole L. “Nikki” DeBlosi ’99 said.

Technology also spread to other corners of the University, including the library system.

“Widener was still using card catalogs, and was just moving over to digitizing everything,” DeBlosi said.”

The increased usage of technology at Harvard followed

the wider technological boom throughout the country, leading to more graduates pursuing jobs in technology after college. Despite that, tech recruiting still took place on a much smaller scale than contemporary recruiting.

“There were not a lot,” Kovacevich said of students pursuing careers in the tech industry. “Microsoft was the most prominent company recruiting people out of college into tech jobs, and there were a couple of people I remember who went to work for Microsoft.”

As the year 2000 approached, the national conversation about Y2K began to dominate as members of the class started their lives after college.

“There was a lot of frantic coverage in the time before the roll-

over, so this was right after we had started working,” Zimmerman said. “There was a lot of questions about, ‘Would the world just sort of turn off when we rolled over from ’99 to 2000?’”

“But of course, it did not,” she added. “It turned out that everything was fine.”

“I think it was a real concern,” DeBlosi said. “The way that I felt about it was like, ‘I already don’t know how this computer works. I’m here reading literature and analyzing pop culture, and probably someone will take care of it, and it will be fine.’” But for Kovacevich, it was not a major concern while the class was still at Harvard.

“I don’t remember it coming up at all,” he said.

aran.sonnad-joshi@thecrimson.com

M. Dershowitz, who was prominently involved in several anti-impeachment rallies, said. “But nobody wanted to see him thrown out of office because of it, because they liked his poli -

The debate around Clinton’s impeachment arrived at The Crimson as well. As The Crimson covered news around the scandal, opinion pieces covering a range of views on the scandal formed much of the campus newspaper’s editorial

“The conservative views were always in the minority,” Geoffrey C. Upton ’99, a former Crimson editorial chair, said. “We did definitely have effort to have some balance.”

By September 1998, the editorial board called on Clinton to resign, though it would oppose impeachment in December 1998, urge the Senate to acquit Clinton a month later, and praise the eventual acquittal in

‘Much More Polarized’ A quarter of a century later, the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal has long fallen from the public eye.

But to some of those who experienced it as Harvard undergraduates, its lessons — and foreshadowing — live on.

At the time of the event, Larson, who worked a few cubicles away from Lewinsky in 1995 as interns, detailed in The Crimson his attempts to speak with media outlets and push back against a “climate of uninformed speculation.”

But over three decades later, some students feel that political discourse in the public arena has not changed for the better.

“What you realize is the degree to which our politics have changed,” Chen said of the years since the scandal. “I’d argue for the worse.”

“We’ve become much more polarized, we’ve become much more partisan. We’ve become a lot more visceral,” he added. “Not that we all got along in 1999.”

The presence of divided government in Washington — Congress, for the first time in decades, had assumed unified Republican control, while the presidency was in the hands of a Democrat — also worked to bring about a degree of partisan polarization, according to Silverstein.

“For the first time in 40 years, there was divided government in Washington,” he said. “It was, I think, the beginnings of the hyper-partisan environment that we’re still living in now.”

idends. “It was a rapid rise and it’s continued,” said Government professor Harvey C. Mansfield Jr. ’53, one of Cotton’s former

the Cotton of today. “Tom was always conservative. I am not. We always differed on a fair amount of political views but we had a shared

conservative as he was at Harvard — as he was as an undergraduate.” Kovacevich, too, works in Washington — serving as the CEO of Chamber of Progress, a left-leaning policy coalition of tech companies.

BY NEIL H. SHAH CRIMSON STAFF WRITERMore than 25 years ago, Tom B. Cotton ’99 helped organize Harvard Model Congress. But playing pretend apparently wasn’t enough. Since his time at Harvard, Cotton has developed a persona of an ambitious politico with a penchant for defending views some find incendiary. The identity stuck as the senator from Arkansas quickly rose through the ranks of Capitol Hill, start ing from his 2013 stint in the House of Representatives to his past two terms in the Senate, where he has emerged as a con servative firebrand whose name regularly appears on shortlists for higher posts.

is vice president of the Unit

ed States of America: the New York Times reported last week that Cotton was among former President Donald Trump’s top five candidates for the post, as his years of committed loyalty to Trump may begin to pay div

Kovacevich suggested Cotton would be excited less by the ideological tilt of an idea than by its novelty and proclivity to provoke.

He read both liberal and conservative magazines — including the New Republic and the Weekly Standard — “because they were a venue for provocative ideas,” Kovacevich said.

He also wrote himself. Cotton ran a column in The Crimson, often assuming conservative stances likely irking or

peers. In one of his final Crimson bylines, titled “Coda,” Cotton addressed his detractors. He described his column as having taken stances “against sacred cows” — like affirmative action — and “in favor of taboo notions,” like “(most unforgivably) conservatism.”

“In retrospect, I have devoted my time at Harvard to cultivating contrarianism,” Cotton wrote, responding to a peer calling him “contrarian.”

“It has not always been a chosen or a conscious endeavor with me, but as my colleague’s comment illustrates, it seems to be a realized one. That most readers would agree with the label only pleases me more,” Cot-

to supplement responses to riots protesting police brutality in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. The piece immediately caused a firestorm. The Times drew significant backlash, with many — including a number of its employees — saying Cotton’s article contained incorrect factual assertions and that his stance would incite further violence.

In a corner, the Times added an editor’s note to the piece, saying it did not meet the paper’s standards and should have been more rigorously edited. Cotton seized on the opportunity

STUDENT TO TEACHER. How David Malan ’99 went from taking Harvard’s flagship course in Computer Science to being the face of it.

BY THOMAS J. METE CRIMSON STAFF WRITEREvery fall, hundreds of students — sometimes as many as 800 — pack into Sanders Theatre for a course that promises to be “an experience,” unlike any other the College has to offer.

“This. Is. CS50,” David J. Malan ’99 announced as he began the first lecture of Harvard’s flagship computer science course CS50: An Introduction to Computer Science. Malan, who took over the introductory computer science course in 2007, has opened each semester since with his signature line. It has become synonymous with his overhaul of the once daunting course — one that is now offered to over 5.8 million students on HarvardX, a free online learning platform.

While today’s students associate Malan — Harvard’s celebrity-like computer science professor — with the swag and fandom surrounding his trademark course CS50, he was first one of 457 students who enrolled in CS50 in the fall of 1996.

“As the saying goes, CS50 changed my life,” Malan wrote in a statement to The Crimson.

Entering college set on concentrating in Government with interests spanning history and constitutional law, Malan never believed he would find himself interested in computer science, let alone concentrating in it, until his sophomore fall — when he came across CS50.

“I finally got up the nerve my sophomore year to shop the course. And for the first time in 19 years (of life), I found that homework could actually be fun,” Malan wrote. “In fact, I used to look forward to going back to my room in Mather on Friday nights, around the time problem sets were released, to dive right in.” Malan said that CS50 changed his perspective on Computer Science, which he had limited exposure to before attending Harvard.

“Contrary to what I’d seen in high school, where I saw friends

of mine programming away in the computer lab, heads down sort of anti-socially, it really wasn’t that,” Malan said in an introductory CS50 lecture on Youtube. “It was much more about problem solving more generally and just learning how to express yourself in code, in different languages, so that you can actually solve problems of interest to you.”

Brian W. Kernighan, a professor of Computer Science at Princeton University, led CS50 as a visiting professor at Harvard. then a visiting professor, would be in charge of leading CS50 in 1996. Kernighan, who co-authored the first textbooks on the C programming language, led Malan’s CS50.

“I never worked so hard in my life,” Kernighan said. Malan still looks back on the “wonderful” teaching methods of Kernighan that have provided inspiration for the innovative approach he takes to teaching his version of CS50 today.

“I still remember him actually cutting his beard during class with, I think, a hedge clipper, to make the point that precision in algorithms is especially import-

ant,” wrote Malan, who is also known for his theatrics during lectures, most notably tearing a phonebook on stage to illustrate an efficient algorithm.

“He presented it in such an accessible way, a trait that hopefully characterizes CS50 today, along with its rigor,” he added.

Following Kernighan’s class — where Malan finished with the eighth highest grade — he felt it “was a sign” to pursue computer science. However, the pair never crossed paths during Malan’s time at the College — it would be over a decade until they would finally meet.

Kernighan has visited Malan’s CS50 course in Sanders Theatre on occasion and said he still learns more ideas and tricks each time.

“He’s just a dynamite presenter. Watching him on the stage is definitely a lot of fun,” he said. “If I was an inspiration in one direction, he’s an inspiration in the other.”

Now, Kernighan and Malan remain in regular correspondence, and are currently working on a project to compile and digi-

tize the video recordings from the 1996 CS50 class which led Malan down his current trajectory.

“I could certainly count him as the high point of my academic success,” Kernighan said.

But to his classmates, Malan’s greatest contributions during his College years were his programming innovations, such as Shuttleboy — a computer program that displayed customized shuttle schedules for students.

Malan, a former Mather House resident, spent over 100 hours creating the computer program after one of his friends who lived in the Quad suggested the idea.

“I always thought it ironic that I, myself, never really took the shuttle,” he wrote.

Shuttleboy was an instant success on campus. The program was first shared through the Pforzheimer House email list, which Malan described as the most popular on campus, and it quickly spread through word of mouth.

“It rather took off from there,” Malan wrote. “At its peak, I think a few thousand undergrads were using it, and it was incredibly ex-

citing to have built something that people were indeed using.”

At the time of its release Malan still insisted that programming was “just a hobby.” But the app outlasted his time as an undergraduate, evolving into new iterations including Shuttlegirl, ShuttleTime, and Shuttleboybot.

Although no longer running the program, Malan maintained contact with the new creators and provided assistance in the development of the application Quad residents grew to love. Before the creation of Shuttleboy — and only one semester after taking CS50 — Malan had already launched his first webbased application, designed to modernize registration for freshmen intramurals. Previously, those interested had to walk to a proctor’s room in Wigglesworth to register.

“I started to teach myself web programming (using a language called Perl) and implemented the program’s first website via which classmates could register online,” Malan wrote. Shortly afterwards, Malan and his roommate, Micol H.

Christopher ’99, took over the intramurals program, with Malan running the website and Christopher, an athlete, leading the scheduling and games.

Beyond coding apps and a failed bid for president of the Undergraduate Council — Harvard’s former student government — Malan also excelled academically. As an undergraduate, he worked as a teaching fellow for an introductory computer science course at the Harvard Extension School. When the professor suddenly stepped down and asked Malan — a college senior at the time — to take over the course as its lead instructor, he said it was a simple case of “right time, right place.”

“I’m pretty sure I ended up being the youngest person in the room, teaching a class of 100 or so adults,” Malan wrote. “I even wore a suit with suspenders whilst teaching in hopes of looking older.” “And that’s the experience that ultimately set me on my way,” he added.

Michelle Obama’s former head speechwriter Sarah K. Hurwitz ’99 found her love for politics at Harvard.

“The more amazing people I saw there — so many public servants who were decent and patriotic and passionate about serving their country — the more I knew I wanted to be part of that,” Hurwitz wrote in an emailed statement.

A former Quincy resident, Hurwitz concentrated in Social Studies as an undergraduate and participated in an afterschool program at the Phillips Brooks House Association and the Undergraduate Council — the previous iteration of Harvard’s student government which was dissolved and replaced by the Harvard Undergraduate Association in 2022.

Dara Horn ’99, Hurwitz’s longtime friend, said she remembers being “inspired” and “stunned” by Hurwitz when they first met in the First-Year Arts Program, one of six orientation programs hosted the week before classes begin in the fall for incoming freshmen.

“She was never interested in sucking up to people. She always was interested in ‘Let’s get down to the real problems here. Let’s cut right to the chase,’” Horn said. “She’s got this sort of assertiveness to her. It’s a problem solving attitude.”

It was that love for politics that drew her to work for Vice President Al Gore ’69 during the summer after her junior year. After initially working on the schedul-

ing and advance team, Hurwitz found her way into speechwriting after she “basically begged” one of Gore’s speechwriters to intern for him.

The foray into a new field didn’t immediately end well. After interning for Nussbaum, Hurwitz later worked for former Senator Thomas R. Harkin, before she was told by Harkin’s chief of staff that she should go to law school — “like ideally right away.”

“I was totally devastated by this – I felt like such a failure,” she wrote.

But after returning to Harvard as a law student she met Joshua S. Gottheimer, who she wrote taught her how to structure a speech and “how you write to be heard, not read — two very different skills.” Gottheimer is now a Democratic congressman from New Jersey.

The two got a job working for Gen. Wesley K. Clark, who unsuccessfully sought the Democratic nomination in 2004, before moving to work for John F. Kerry, who would lose the general election to George W. Bush.

When the next election cycle began, Hurwitz was working as a lawyer in D.C. before Gottheimer encouraged her to work for Hillary Clinton’s 2008 presidential campaign. Clinton would lose the nomination to Barack Obama, whose chief speechwriter Jon E. Favreau knew Hurwitz from the Kerry campaign. Favreau hired her.

Obama’s victory, which Hurwitz wrote was “a new and exciting experience for me,” led her to the White House, where she stayed for the entirety of the

Obama administration.

During Obama’s campaign, Hurwitz assisted Michelle Obama with her speech for the 2008 Democratic Convention, and “really hit it off with her,” occasionally helping her with speeches while writing for the former president.

“Eventually, I realized that I actually felt more at home in Mrs. Obama’s voice and was more interested in the issues she was speaking about,” Hurwitz wrote.

“In a very unusual White House career move, I decided to go from writing for him to being head speechwriter for her.”

Hurwitz wrote she “absolutely” hates it when she receives comments like “‘putting words in Michelle Obama’s mouth.’”

“The idea that anyone would put words in her mouth is absurd,” Hurwitz wrote. “The vast majority of the time you’ve ever seen her, she isn’t giving a speech. And what you see — her intelligence, compassion, devotion to the causes she cares about — that’s her. The job of a speechwriter is to do their best to channel it.”

“I want to be clear that I did not come up with the line ‘When they go low, we go high.’ Mrs. Obama came up with that line – all I did was type it into the speech,” she wrote.

When the Obamas left the White House in 2017, Hurwitz left speechwriting.

In what she calls her “current life,” Hurwitz says she “is focused largely on speaking about and writing books about Judaism” after reconnecting with the faith as an adult, something she said she found “incredibly challenging.” She published a book on the top-

ic in 2019. She returned to Harvard in the spring 0f 2017 as a study group fellow at the IOP, where her sessions were attended by Amanda S.C. Gorman ’20, who garnered fame as the youngest U.S. Poet Laureate

David Malan ’99 explains the concept of binary in a CS50 lecture in Sanders Theatre. ALANA M. STEINBERG — CRIMSON PHOTOGRAPHER

David Malan ’99 explains the concept of binary in a CS50 lecture in Sanders Theatre. ALANA M. STEINBERG — CRIMSON PHOTOGRAPHER

House’s charges were from the beginning.

The Senate’s vote last week to acquit the president on charges of perjury and obstruction of justice came as little surprise. Despite desperate last-minute attempts to bolster their case with yet another round of testimony from witnesses, the House impeachment managers throughout the trial were unable to provide a compelling explanation for how the president’s actions in the Monica Lewinsky affair met the constitutional standard of “high crimes and misdemeanors.” Neither charge could muster a simple majority, a sign of how weak the

The vote marked the end of a sad saga that has mesmerized Washington and disgusted the nation for more than a year. A story of two villains--Bill Clinton and Ken Starr--and no heroes, this all-encompassing scandal has claimed many victims: Newt Gingrich, Bob Livingston, the Republican Party’s approval ratings and Bill Clinton’s place in the history books. The already low esteem most Americans hold for government has only fallen more. In December, after House Republicans forced two articles of impeachment through on an almost completely partisan vote, it seemed the nation was in for the nadir of American politics: a protracted, parti-

san trial in the upper house.

But in the end, the Senate performed admirably. Senators resisted calls to short-circuit the trial required by the Constitution, while preventing the proceedings from dragging on longer than necessary. Though Republican senators did ram through several procedural votes along party lines, the trial as a whole bore little resemblance to the partisan fray in the House.

Many have promoted censure as the appropriate punishment for the president’s crimes. But in the wake of the Senate vote, no formal censure resolution appears likely. Legitimate constitutional questions and an overwhelming desire to put the im-

peachment adventure in the past have doomed the movement for censure, at least for the moment. But Clinton should not interpret this as an exoneration. As Senator Daniel Inouye of Hawaii noted, each senator has censured Clinton in his or her own way, and there is little a Congressional resolution could do to add to this universal condemnation.

No one can easily undo the damage our president and his accusers have done to the nation--to the quality of our political discourse, to our standing abroad, to our faith in the political system. Rebuilding trust and civility in government will be perhaps the most urgent and difficult task awaiting President Clinton’s successor.

To a generation of college students much maligned for its apathy, the events at Harvard today might seem a little unusual. While the Faculty meets inside University Hall this afternoon, three separate groups of protestors will converge on the Yard in what will probably be one of the larger demonstrations at Harvard in years. The agenda of the three groups are very different--two are calling for the University to adopt new labor policies while the third is calling for the expulsion of a student convicted of sexually assaulting another student--but they have thrown their lots together today.

The great mystery is how--or even if--the Faculty will respond to the protests. Each group has made reasonable complaints and deserves a sincere response from the University. Thus far, Harvard has listened to each of the groups but has taken no serious action on any of their demands. Perhaps the sight of hundreds of protestors marching outside University Hall will convince Harvard to take its own students more seriously. We certainly hope so.

We endorse the causes behind today’s demonstrations and challenge the administration to give each group a fair and separate hearing. The issues raised here strike at the heart of the University’s relationship with the world, with its employees

and with its own students.

As one of the most prestigious educational institutions, Harvard enjoys an enormous degree of power and influence in the embattled world outside its gates. For this reason, the University cannot--in good conscience--avert its eyes in the face of society’s gravest ills. For this reason we urge the University to adopt stricter policies against manufacturers who exploit “sweatshop” labor to produce Harvard insignia apparel. The Progressive Student Labor Movement (PSLM) has rightly demanded such manufacturers be required to disclose factory locations and allow non-governmental organizations to inspect working conditions. If these manufacturers fail to meet these terms, Harvard should terminate its licensing contract. It would be a serious error to underestimate the importance and scope of the issue. Conditions in these factories are nothing short of inhumane: Sweatshops subject their workers to long hours, physical and verbal abuse, unsanitary drinking water, poor-ventilation and disease-carrying parasites. They frequently employ child labor. And wages are as low as 12 cents an hour.

According to Allan A. Ryan Jr., an attorney at the Office of the General Counsel and Harvard’s chief negotiator on the issue, the University will not adopt a separate policy until the Ivy League schools work out a uniform agreement. But someone has to take the first step, and this leadership

responsibility should fall onto Harvard’s shoulders. A successful University code against sweatshops--one which has involved students in its development and implementation--would send a powerful message to the outside world.

Harvard’s responsibility also extends to its own labor practices. This afternoon, protestors from the Harvard Living Wage Campaign, marching alongside the PSLM, will demand that the University set a $10 per hour minimum wage for all its employees, a level the City of Cambridge has declared as the “minimum living wage.”

Such a policy is both feasible and just. For Harvard, the additional costs of the policy would be but a drop in the vast budget bucket. More than 1,000 employees hired under subcontract currently earn barely enough to stay above the poverty line. As many of these workers must support families at home, it is ironic that their wages are significantly lower than those earned by most part-time students on the Harvard payroll.

The University has claimed it has no responsibility for the wages of these employees since they are hired under subcontract. Nevertheless, subcontracted workers are still Harvard workers. Surely the University can do better.

The most complicated demand the Faculty will hear today is for the expulsion of D. Drew Douglas, Class of 2000. Douglas has been found guilty in criminal court of indecent assault on another student and the Administrative Board de -

termined that a rape occurred. Based on the Ad Board’s findings, the Faculty is scheduled to vote on dismissal--not expulsion. This has not stopped the Coalition Against Sexual Violence from calling for expulsion, though the demand has no realistic chance of succeeding. We agree that the crime of rape should require expulsion and reject as hyperbolic the analogy, popular among administrators, that expulsion is the College’s “death penalty.” Though the protest today may seem futile, it is important nonetheless for the administration to see there are few crimes more offensive to the campus community than rape. If and when future cases of rape come before the Faculty, a vote on expulsion--and no lesser punishment--should be on the agenda. Regardless of how many students turn out this afternoon, the protest today promises to be a unique occurrence at Harvard. The three student groups leading the protests, all fighting for different worthy causes, have in common only an unreceptive administration. There are two ways the University can respond. It can, easily enough, pay simple lip service while avoiding any substantive action. Or it can commit to a sincere and constructive dialogue with students on these legitimate concerns. We will be watching; Harvard’s decision will reflect how deeply the administration values student opinion on this campus.

The women’s ice hockey team had a stellar run in 1999. JULIAN J. GIORDANO — CRIMSON PHOTOGRAPHER

WOMEN’S ICE HOCKEY

TRIPLE CROWN. Harvard’s women ice hockey team had a revered season in 1999, including a championship run.

BY JACK ANDERSON CRIMSON STAFF WRITEROn March 27, 1999, in Minneapolis, Minn., the No. 1 ranked Crimson team took the ice against the No. 2 University of New Hampshire Wildcats in the NCAA women’s ice hockey national championship game. After three periods of backand-forth battling, the two squads entered overtime with the biggest prize in all of college hockey on the line: the national championship trophy. While most teams would be panicking in this situation, Harvard, with only one loss under its belt throughout the entire 34-game season, knew what it had to do.

The Crimson stayed calm and collected, defeating UNH in a nail-biter that clinched not just the championship, but also the coveted “triple crown” of victories — the Ivy League, the Beanpot, and the National Championship — putting the cherry on top of its historic season.

“Going into that year, Harvard had always been a building program,” AJ Mlezcko, a star forward for the 1999 squad, said in a past interview with the Crimson. “The big three that nobody could touch were UNH, Northeastern, and Providence College.”

The team started the season

3-0, an impressive start for the squad. In its fourth game of the season, it lost to Brown 2-4. This was a loss that it did not expect, and it lit a fire that catalyzed a new level of intensity for its remaining games. After that loss, the team won 30 games straight, including the Beanpot Championship, the Eastern Conference Championship, and the National Championship. The team defeated the UNH Wildcats, the alma mater of Head Coach Katey Stone, in both the Eastern Conference Athletic Conference finals (ECAC) and the American Women’s College Hockey National Championship (AWCHA).

The team’s 33-1 record may suggest that the entire season was easy skating. However, while some games had dominant performances, like a 9-0 win over Boston College in the Beanpot and a 15-0 win against Colby, the season was not a walk in the park.

The team sustained injuries just like any other, including one devastating blow to then-junior goalie Crystal Springer, who broke her collarbone during the regular season. After returning later during the season, disaster struck against Brown during its 5-3 victory in the AWCHA semi-final. Springer broke her collarbone again, forcing rookie goalie Allison Kuusisto to step up between the pipes for the National Championship game against UNH.

The Crimson was resilient though, proving that truly great teams adapt to the challenges that emerge throughout a season. Harvard rallied and came back to lead by two late in the

championship game. After two goals from the Wildcats, it was even, and the two teams were headed to overtime in Minneapolis. After eight minutes of overtime, Botterill ended the game, assisted by Mlezcko, giving Harvard its 33rd win and most importantly, the National Championship.

In addition to the Bean Pot, Ivy title, and National Championship, Stone would also take home ECAC Coach of the Year, the New England Hockey Writers’ Coach of the Year, the American Hockey Coaches Associ -

Hockey team in the Olympics, coaching the women’s team to a silver medal in Sochi.

“I think the proudest thing for me — and we just had a celebration of the ’99 team, and many of our players were able to come back — is just how connected they were, and how connected they still are,” Stone said in 2019, looking back. “And I just think that that’s a testament to their character and how much it meant to them.”

What made the victory even sweeter for the Harvard team was that it marked the 25th an -

We knew that we just had to spread them out and use our depth. We had so many good players on that team.

AJ Mlezcko

Forward, 1999 Women’s Ice Hockey Team

ation Women’s Coach of the Year, and New England College Athletic Conference Division-I Coach of the Year. Stone would end her career with 494 victories in 25 seasons as Head Coach for the Crimson. Stone started her tenure as Head Coach in 1994. After three years of sub-.500 performances, the team jumped from 1416-0 in the 1998 season to 33-10 in the famed 1999 campaign. During the 2014 season, Stone became the first woman ever to be named Head Coach of a USA

niversary of the program’s recognition as a Harvard University squad under Title IX. With the gravitas of this milestone, and the trophy on the line, the Crimson team proved that it was up to the challenge.

“In terms of that intermission [before overtime], going in, I think it was more a matter of ‘We’ve got this,’” Mlezcko said. Mlezcko was no stranger to big situations like this, as a twotime Olympian and 1998 gold medalist. “We knew that we just had to spread them out and use

our depth. We had so many good players on that team.”

Alongside this historic performance, Mlezcko was awarded the 1999 Patty Kazmaier Award, given to the top-performing women’s player in college hockey. In 2002, Mlezcko was inducted into the New England Women’s Hall of Fame and Polish-American Sports Hall of Fame. She later became the first woman to ever commentate for a National Hockey League game and now works as a color commentator for ESPN and ABC, calling games for the New York Islanders.

In the overtime period of the championship game, freshman Jennifer Botterill netted the decider, her eighth game winning goal of the year, putting an exclamation point on the squad’s already dominant season. The score was Mlezcko’s whopping 77th assist of the season.

Botterill’s successes, alongside her team’s, would not be confined to just that one season, and she would go on to win the Kazmaier twice in the next three years, in 2001 and 2003. Additionally, at the time of the national championship game, Botterill had already proved herself on a national stage, having clinched an Olympic silver medal. The standout would go on to win the gold medal in the 2002 games in Salt Lake City, at the 2006 Winter Olympics in Turin, and at the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, playing forward. She also went on to play three seasons in the National Women’s Hockey League and three in the Canadian Women’s Hockey League.

She now works as a color commentator and studio analyst for TNT.

The 1999 roster has produced some of the Crimson’s most renowned hockey champions, which has established a precedent of excellence for the program. Tammy Lee Shewchuck also played a pivotal role in the win in Minneapolis. After the season, she would be named a first team All-American. She would also go on to win the Olympic gold medal in 2002 alongside Botterill in Salt Lake City. At the time of her graduation from Harvard, Shewchuck earned herself the title of NCAA alltime leading scorer. After college, Shewchuck took her talents to the coaching scene, leading teams at Lawrenceville and Wesleyan. “That line [Mlezcko, Botterill, Shewchuk] was one of the best lines in college hockey ever, and there’ve been a couple others since,” Stone reminisced. “What those kids were able to do together ... was huge. They weren’t all great friends all the time, but they knew that they were the right three to play together.”

A quarter of a century later, the Crimson’s ice hockey stars can still look back and appreciate the legacy of the stars that came before them. As the team continues in a new era under Head Coach Laura Bellamy ‘13, the successes of Mlezcko, Botterill, Shewchuk, and Stone offer a blueprint for future success.

Meeting brilliant, interesting people shouldn’t end just because you graduated. Join the Harvard Club of Boston and make the club your new home base for all things Harvard. WHERE EVERY DAY IS YOUR

Join our community DINING | CO-WORKING | OVERNIGHT ROOMS | NOTABLE EVENTS GLOBAL RECIPROCAL NETWORK | ATHLETICS