PLAGIARISM WEAPONIZED

Gay’s resignation showed how plagiarism has become the right’s culture war weapon of choice.

PLAGIARISM WEAPONIZED

Gay’s resignation showed how plagiarism has become the right’s culture war weapon of choice.

SIDECHAT TOXICITY

After Oct. 7, Sidechat became a platform for students to anonymously engage in heated debates.

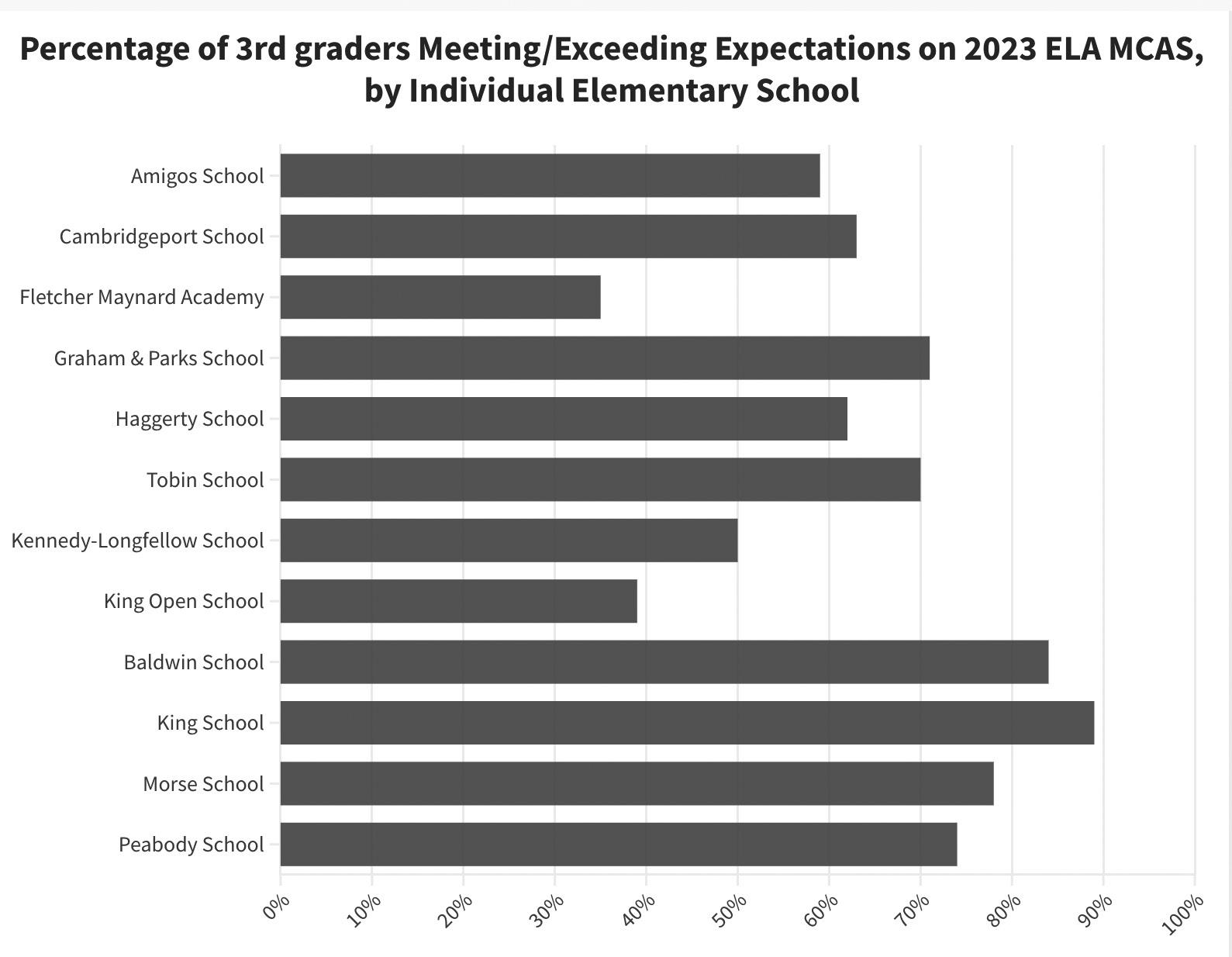

EDUCATIONAL EQUITY

Standardized English curriculum takes aim at racial inequities among Cambridge students.

DISTRICT DIPLOMACY

Harvard President Alan Garber is traveling to Washington to smooth things over with politicians.

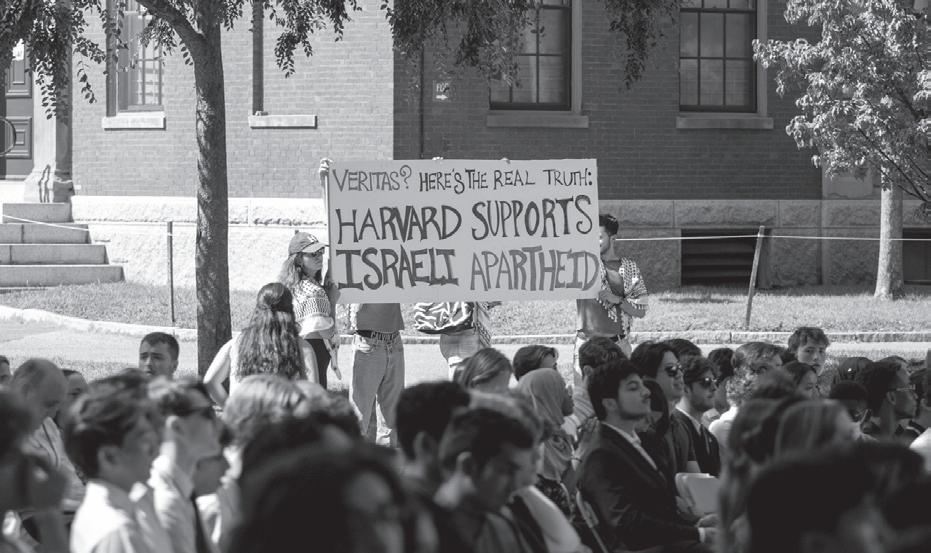

ACTIVIST ANGER

Campus activists allege Alan Garber’s administration has attempted to crackdown on protests.

Year in Review STAFF

MANAGING EDITOR

Miles J. Herszenhorn ’25

ASSOCIATE

MANAGING EDITORS

Elias J. Schisgall ’25

Claire Yuan ’25

DESIGN CHAIRS

Sami E. Turner ’25

Laurinne Jamie P. Eugenio ’26

MULTIMEDIA CHAIRS

Julian J. Giordano ’25

Addison Y. Liu ’25

STORY EDITORS

Hewson Duffy ’25

Yusuf S. Mian ’25

John N. Peña ’25

Rahem D. Hamid ’25

Paton D. Roberts ’25

Jem K. Williams ’25

COVER DESIGNER

Sami E. Turner ’25

PRESIDENT

J. Sellers Hill ’25

BUSINESS MANAGER

Matthew M. Doctoroff ’25

ASSOCIATE BUSINESS MANAGERS

Mathias Melucci ’26

Meredith W.B. Zielonka ’25

4

Here are the key moments that shaped Harvard’s most tumultuous year in decades.

The most memorable statements, spoken and written, that made it onto the pages of The Crimson in 2023-24.

9

13

Faculty watched Harvard’s crises from the sidelines. Now, they want a seat at the table.

How academia’s cardinal offense became the right’s culture war weapon of choice.

27

Graduating seniors reflect on a Harvard journey bookended by the Covid-19 pandemic and campus turmoil.

8 34 37

Conferences or Vacations?

How Harvard students get all-expenses paid international trips to staff conferences organized for high schoolers.

31

The Rise of Sidechat

It was a place for memes and clout-chasing. Then Oct. 7 changed student interactions on the anonymous platform.

Searching for the 31st

Whether the Harvard Corporation likes it or not, it will send a politcal message with its pick to be Harvard’s next president.

Harvard Medical School students are navigating the new moral and emotional challenges of a post-Covid-19 world.

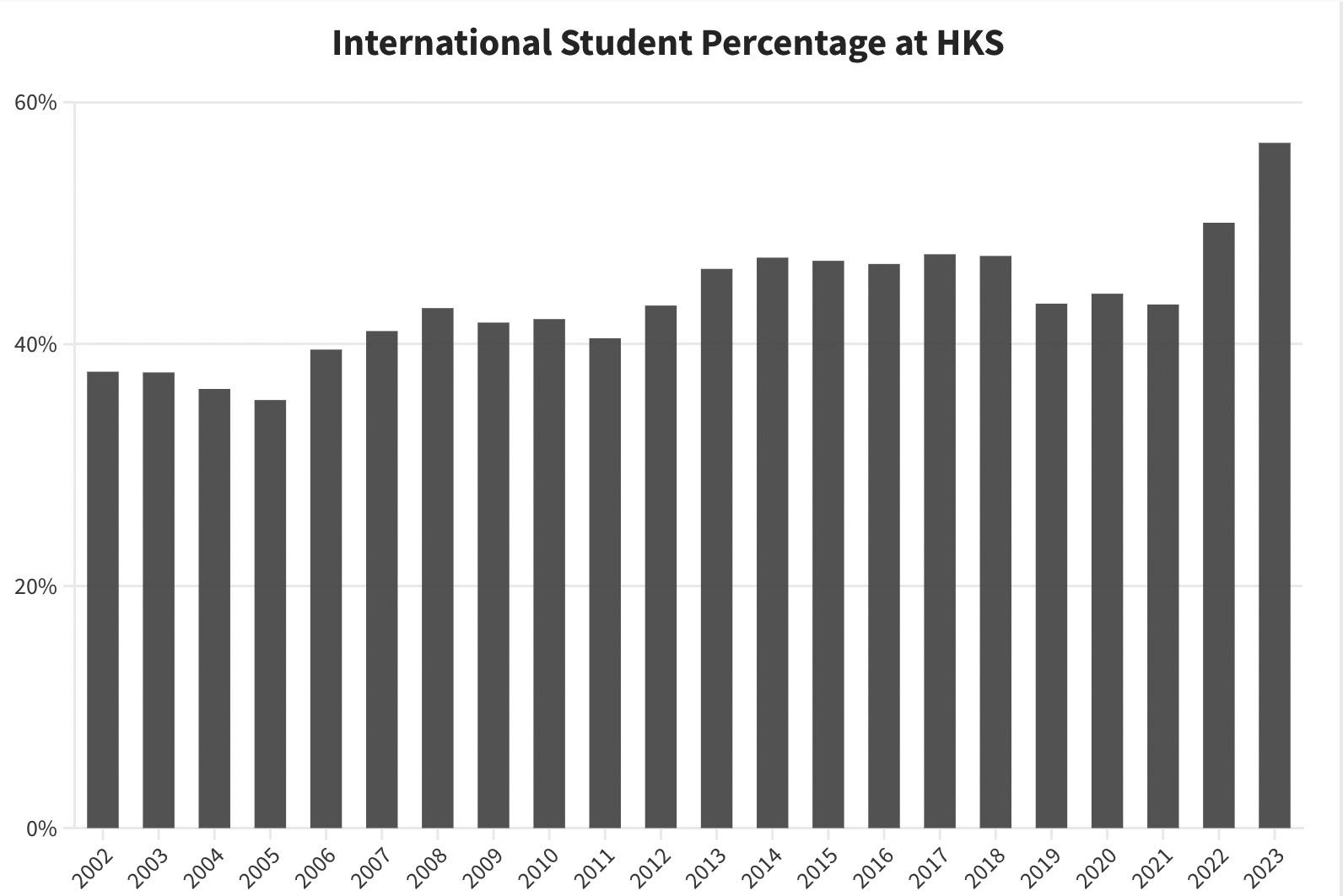

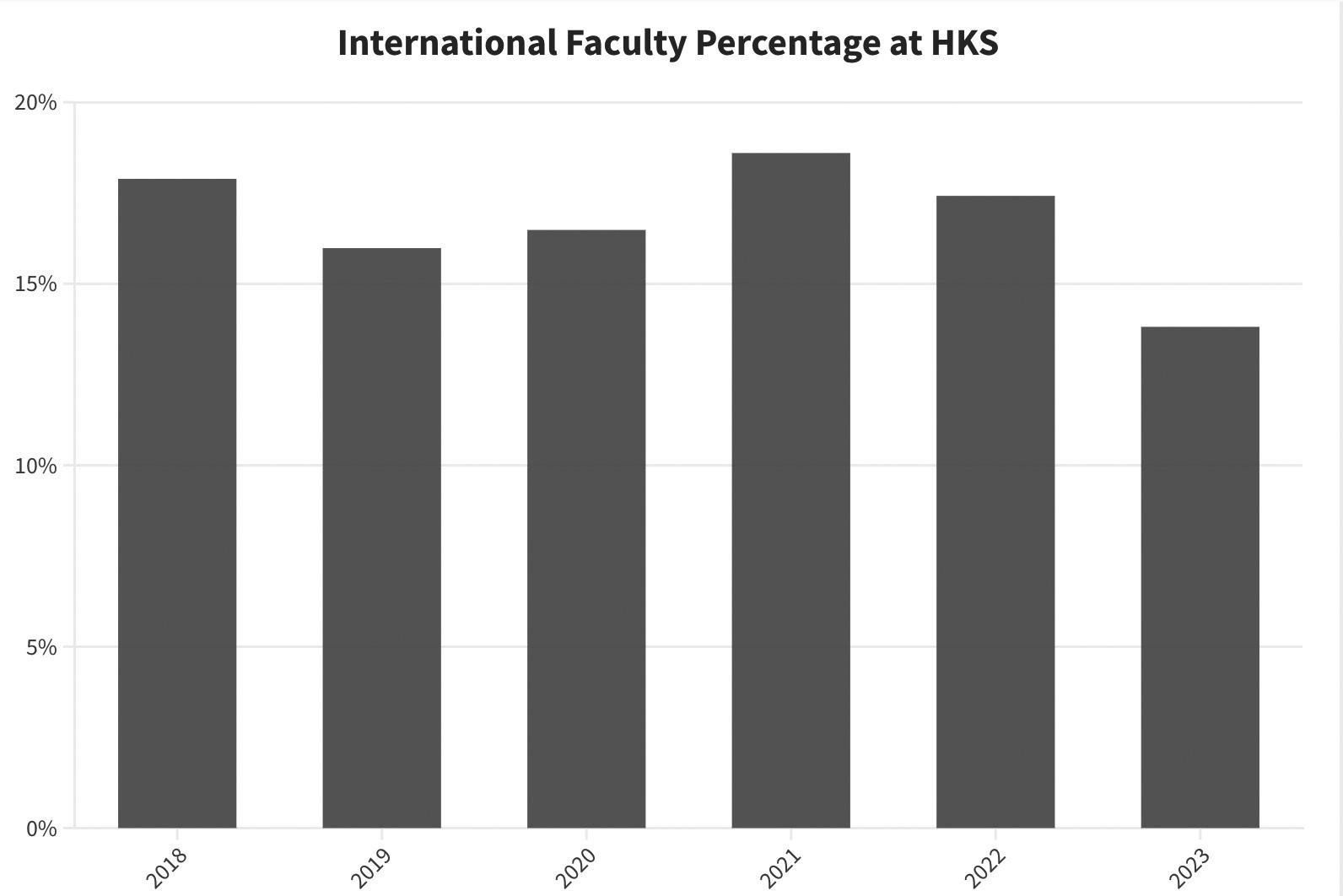

The Harvard Kennedy School’s student body is 56% international. But some say the curriculum still needs to catch up.

47

50

53

56

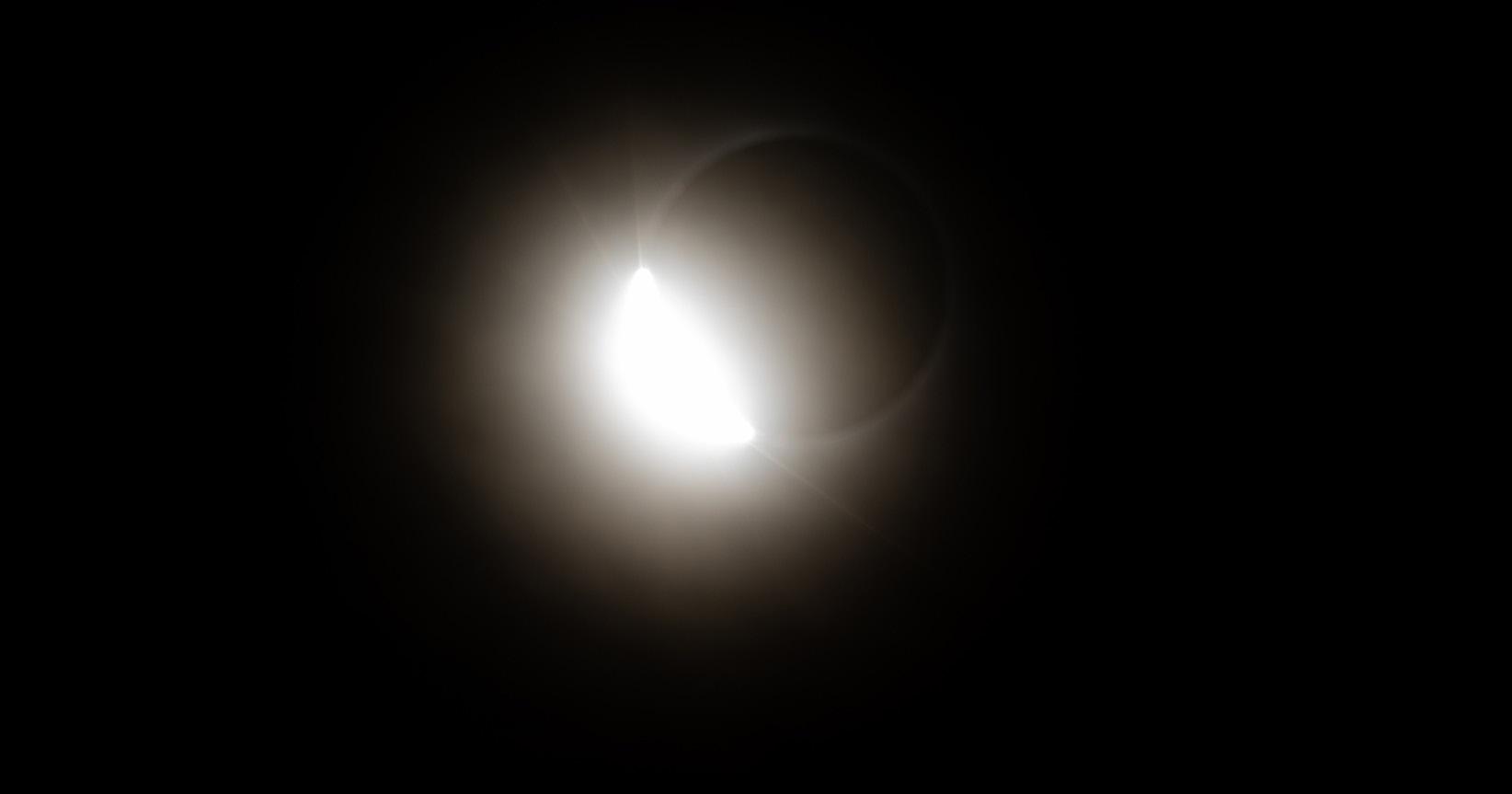

From Claudine Gay’s congressional testimony to the pro-Palestine encampment, see last year’s top moments in photos.

Standardized English curriculum takes aim at the racial achievement gap among Cambridge students.

From mice and broken appliances to inaccessible spaces, students say College dorms could use a facelift.

Allston is emerging as a new hub for the booming biotech industry — with a little help from Harvard.

Athletic admissions remain relatively unchanged — even in a year of an evolving admissions landscape.

61

66

Alan Garber is visiting lawmakers in Washington as he seeks to rebuild Harvard’s relationship with politicians.

Meet the man who served as the chief architect of Harvard’s admissions program through turmoil in court.

70

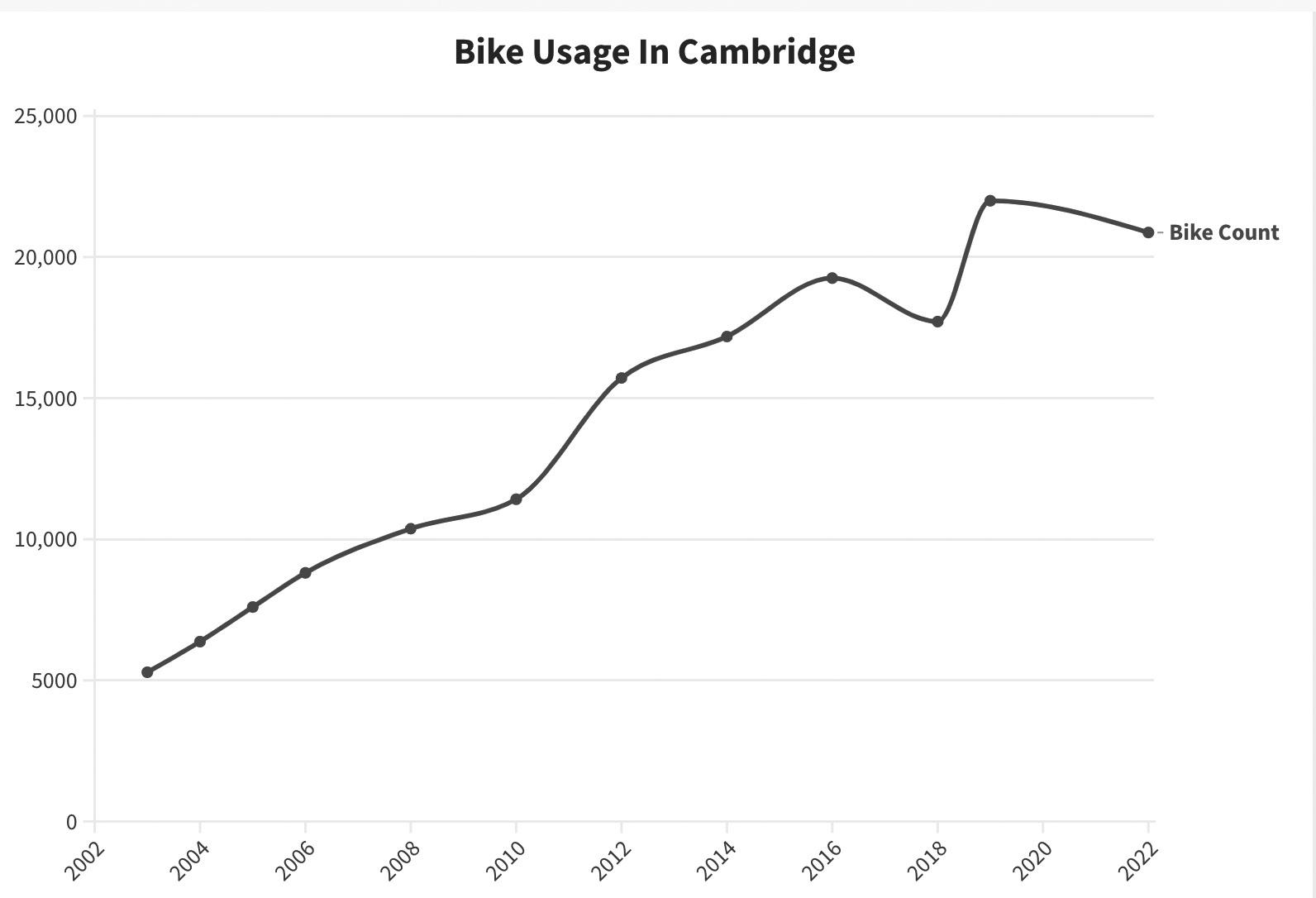

How separated bike lanes became the most divisive political issue in the city of Cambridge.

73

79

83

Some protesters condemned interim Alan Garber’s approach to student activism as repressive and forceful.

Harvard’s non-tenure-track faculty unionized — and they want better employment conditions.

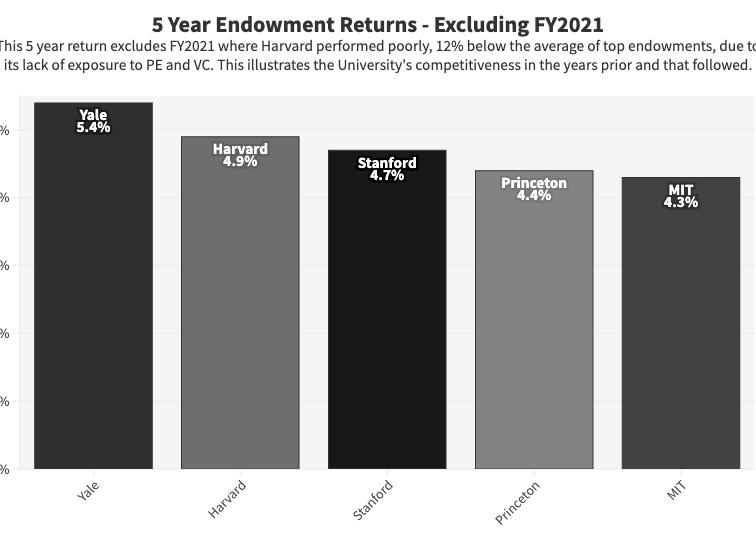

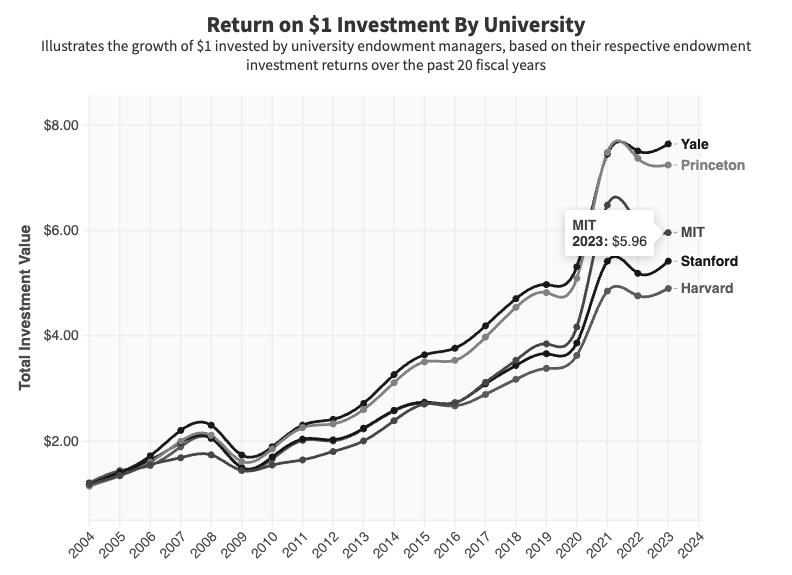

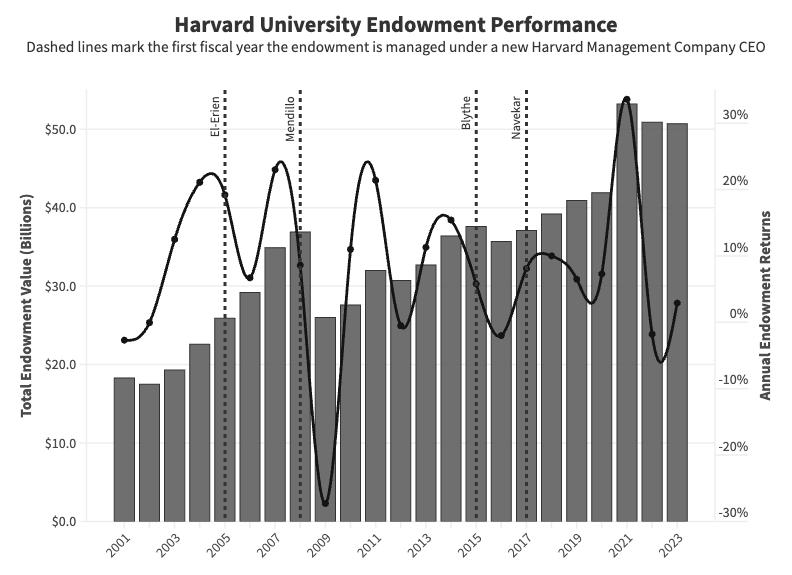

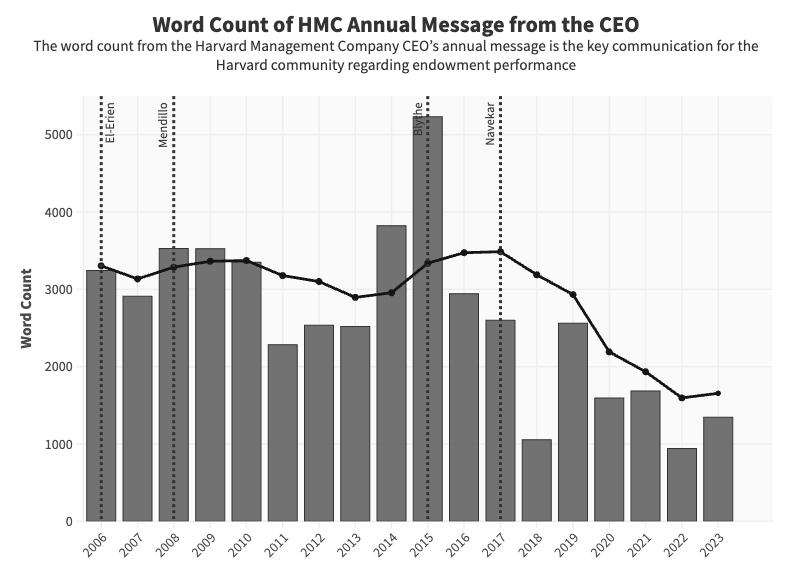

Harvard’s $50.7 billion endowment is the largest in higher education. Some say it is underperforming.

June 29, 2023

AFFIRMATIVE ACTION FALLS

In a 6-2 decision, the Supreme Court declares Harvard’s race-conscious admissions policies unconstitutional, effectively ending affirmative action.

July 1, 2023

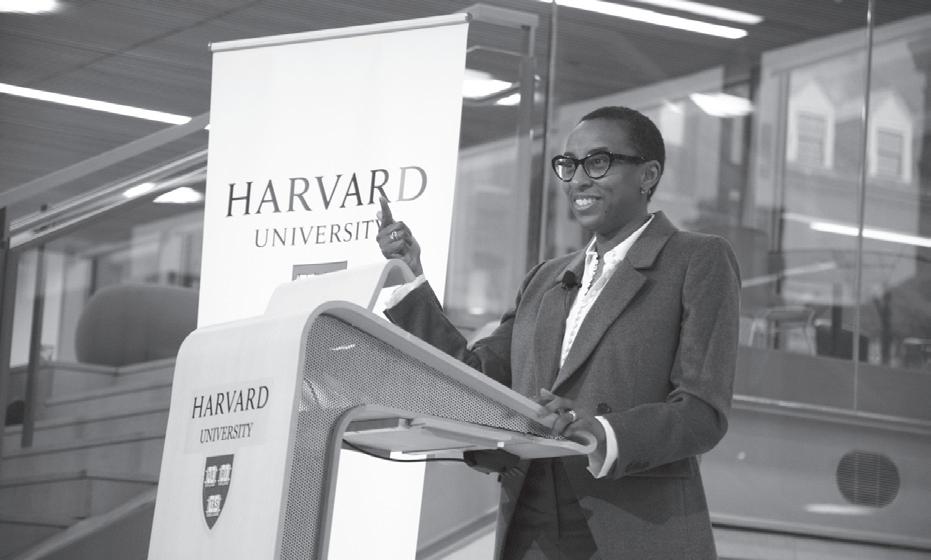

CLAUDINE GAY TAKES OFFICE

Claudine Gay takes office as Harvard’s 30th president, becoming the first person of color to lead the University.

Oct. 11, 2023

GAY CONDEMNS HAMAS ATTACK, DISTANCES UNIVERSITY FROM PSC STATEMENT

Two days after the University’s first statement addressing the conflict and facing national backlash from the PSC statement, Gay asserts that student groups do not speak for the University or its leadership.

Nov. 9, 2023

GAY CONDEMNS ‘FROM THE RIVER TO THE SEA’

In an email to Harvard affiliates, Gay reaffirms a commitment to combating antisemitism and explicitly condemns the phrase “from the river to the sea.”

July 25, 2023

DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION OPENS INVESTIGATION INTO HARVARD’S DONOR AND LEGACY ADMISSIONS PRACTICES

Nearly a month after the fall of affirmative action, the U.S. Department of Education opens an investigation into Harvard’s legacy and donor admissions practices.

Nov. 17, 2023

HARVARD JEWS FOR PALESTINE OCCUPY UNIVERSITY HALL

Nine pro-Palestine student organizers occupy University Hall for just over 24 hours, demanding a call from Harvard for a ceasefire in Gaza. Eight students would later face Ad Board hearings.

Sept. 29, 2023

CLAUDINE GAY’S INAUGURATION

Gay formally assumes her role as president during a festive inauguration ceremony in Tercentenary Theatre.

Oct. 9, 2023

100 DAYS OF GAY

The 100th day of Gay’s tenure as president of the University coincided with her administration’s first public statement about Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack on Israel.

Oct. 10, 2023

STUDENT GROUPS FACE BACKLASH FOR LETTER HOLDING ISRAEL “ENTIRELY RESPONSIBLE” FOR HAMAS ATTACK

Harvard students draw campus and national backlash in response to a letter from the Harvard Undergraduate Palestine Solidarity Committee and signed by more than 30 student organizations holding Israel “entirely responsible” for an Oct. 7 attack by Hamas.

Nov. 28, 2023

U.S. EDUCATION DEPARTMENT OPENS INVESTIGATION INTO HARVARD OVER ANTISEMITISM COMPLAINT

The U.S. Department of Education opens an investigation into Harvard following a complaint alleging the University’s failure to respond to reports of antisemitic harassment on campus.

Dec. 5, 2023

GAY TESTIFIES BEFORE CONGRESS Gay appears before Congress in a hearing about antisemitism on college campuses. When pressed on whether calling for the genocide of Jews violates Harvard’s rules on bullying and harrassment, Gay says “it depends on the context.”

Dec. 7, 2023

GAY APOLOGIZES FOR REMARKS DURING CONGRESSIONAL TESTIMONY

In an interview with The Crimson, Gay apologizes for her remarks during her congressional testimony, which included an exchange with Rep. Elise M. Stefanik ’06 (R-N.Y.) that sparked national outrage and led to calls for Gay’s resignation.

Dec. 12, 2023

CORPORATION BACKS GAY, ACKNOWLEDGES PLAGIARISM ALLEGATIONS

The Harvard Corporation, the University’s highest governing body, unanimously voices support for Gay amid calls for her resignation. Addressing allegations of plagiarism against Gay, the Corporation announces correction requests to two of her articles “to insert citations and quotation marks that were omitted from the original publications.”

Feb. 16, 2024

HOUSE REPUBLICANS SUBPOENA HARVARD’S TOP BRASS

Republicans on the House Committee on Education and the Workforce subpoena three top Harvard officials, demanding internal documents and communications to investigate Harvard’s handling of campus antisemitism.

Jan. 2, 2024

GAY RESIGNS, GARBER ANNOUNCED AS INTERIM PRESIDENT

Gay resigns as president after just six months and two days at the helm — the shortest ever tenure of a Harvard president. University Provost Alan M. Garber ’76 is announced as Harvard’s interim president.

Jan. 3, 2024

CORPORATION SENIOR FELLOW PRITZKER REBUFFS CALLS TO RESIGN

A Harvard spokesperson says Harvard Corporation Senior Fellow Penny S. Pritzker ’81 will not resign despite calls for her resignation from prominent donors and alumni.

March 1, 2024

LAW SCHOOL DEAN MANNING NAMED INTERIM PROVOST

Garber appoints Law School Dean John F. Manning ’82 as the University’s Interim Provost. Manning was an internal finalist during the presidential search that ultimately ended with Gay’s selection.

April 22, 2024

HARVARD SUSPENDS PALESTINE SOLIDARITY COMMITTEE

The College suspends the Harvard Undergraduate Palestine Solidarity Committee, ordering the group to end “all organizational activities” for the remainder of the spring semester.

Jan. 31, 2024

KEN GRIFFIN PAUSES DONATIONS

Billionaire Harvard megadonor Kenneth C. Griffin ’89 announces he will pause donations to Harvard over its handling of antisemitism on campus, but leaves open the possibility of the University regaining his support.

Feb. 4, 2024

BAE AND FRAZIER JOIN CORPORATION AHEAD OF PRESIDENTIAL SEARCH

Kenneth C. Frazier, former longtime CEO and chairman of Merck & Co., and private equity billionaire Joseph Y. Bae ’94 join the Harvard Corporation.

Feb. 6, 2024

DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION OPENS INVESTIGATION INTO HARVARD FOLLOWING ANTI-PALESTINIAN DISCRIMINATION COMPLAINT

The U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights launches an investigation into Harvard following a complaint alleging antiPalestinian discrimination filed by Muslim Legal Fund of America.

April 25, 2024

PRO-PALESTINE PROTESTERS BEGIN ENCAMPMENT IN HARVARD YARD

Pro-Palestine protesters begin an encampment in Harvard Yard, rallying against the College’s suspension of the Palestine Solidarity Committee and calling for University divestment from the University in Gaza.

April 30, 2024

CONGRESSIONAL INVESTIGATION INTO ANTISEMITISM ON COLLEGE AND UNIVERSITY CAMPUSES EXPANDED TO HOUSE-WIDE PROBE

The House Committee investigation into antisemitism on college campuses expands into a House-wide probe as representatives from several colleges are called to testify before Congress. In an April interview with The Crimson, Garber said he would testify in Congress if asked to do so.

May 10, 2024

HARVARD PLACES 20 ENCAMPED PROTESTERS ON INVOLUNTARY LEAVE

Two weeks after protesters set up an encampment in Harvard Yard, the University places 20 students on involuntary leaves of absence.

From Harvard’s joyous presidential inauguration to a sudden presidential resignation and the appointment of a new administration, The Crimson covered the major events of 2023-24. Read some of the year’s key moments in the words of the people impacted by these stories.

Serving as your president has been the privilege of my life.

LAWRENCE S. BACOW

We demand that the University take action to address the harm caused and protect the mental, emotional, and physical safety of Black students.

This is not a normal court.

JOE BIDEN

MAY 2023 JUNE 2023 SEPT. 2023 OCT. 2023

PETITION

400 Harvard students signed a petition to demand more support following a swatting attack against four Black students.

I stand before you today humbled by the prospect of leading Harvard, emboldened by the trust you have placed in me, and energized by your own commitment to this singular institution and to the common cause of higher education.

CLAUDINE GAY

JULY 2023

I will not remain silent as SFFA tries to use Asian Americans as a racial wedge or their model minority, because as an Asian American, I choose solidarity, not silence.

REBECCA S. ZHANG ’26

Harvard students rallied on campus to denounce the Supreme Court’s ruling and show support of affirmative action.

I cannot fathom the Administration’s failure to disassociate the University and condemn this statement.

LAWRENCE H. SUMMERS

Our community must understand that phrases such as ‘from the river to the sea’ bear specific historical meanings that to a great many people imply the eradication of Jews from Israel and engender both pain and existential fears within our Jewish community. I condemn this phrase and any similarly hurtful phrases.

CLAUDINE GAY

I am the interim president, but the problems we need to deal with are not interim problems.

ALAN GARBER

resignation.

Claudine Gay, Harvard’s 30th president, delivered a speech during her inauguration ceremony in Tercentenary Theatre in front of dozens of higher education leaders and hundreds of students and faculty who sat through the lengthy event despite the torrential downpour.

It has become clear that it is in the best interests of Harvard for me to resign so that our community can navigate this moment of extraordinary challenge with a focus on the institution rather than any individual. I am sorry. Words matter.

CLAUDINE GAY

Former Harvard President Claudine Gay apologized to Jewish affiliates on campus for her remarks during a congressional hearing about antisemitism on college campuses

CLAUDINE GAY

Claudine Gay resigns as president of Harvard, becoming the shortest-serving president in University history.

I would be surprised if John Manning returns to the Law School.

MICHAEL J. KLARMAN

After Garber told The Crimson that he did not intend to return to his role as provost, Garber appointed Harvard Law School Dean John F. Manning ’82 as his interim provost.

Standardized tests are a means for all students, regardless of their background and life experience, to provide information that is predictive of success in college and beyond.

HOPI E. HOEKSTRA

Faculty of Arts and Sciences Dean Hopi E. Hoekstra announced Harvard would reinstate its standardized test requirement in admissions for the Class of 2029.

A SEAT AT THE TABLE. After months of watching Harvard endure crisis after crisis from the sidelines, the faculty — the University’s “sleeping giant” — have risen from their slumber. A group of prominent professors is pushing for a Harvard-wide faculty senate, and even those who oppose the proposal agree governance change is needed.

On April 30, after months of watching the University endure crisis after crisis from the sidelines, the Faculty of Arts and Sciences packed into a lecture hall to finally hear the Harvard Corporation’s side of the story.

At that meeting, the first of its kind in living memory, the Corporation — Harvard’s top governing body — found a very different professoriate from the one it oversaw just a few months prior: one more engaged, more disillusioned with the University’s governance, and looking to assert a more powerful voice.

Former Harvard President Drew Gilpin Faust “doubled the number of the Corporation from 6 to 12,” one professor noted, according to an attendee’s transcript of the town hall. “This is the first time in 22 years that I’ve seen any of them.”

“Is there a feedback loop by which the Corporation could correct course as a result of criticism?” another asked. “At the moment, the Corporation has no oversight.”

The frustration that faculty have no direct line to top leadership isn’t limited to Harvard’s secretive governing boards.

At a May 7 FAS meeting, when interim Harvard Provost John F. Manning ’82 said interim Harvard President Alan M. Garber ’76 was unaware of meeting requests by students and faculty members to discuss campus issues related to the war in Gaza, faculty members in the audience laughed and groaned.

“That’s a sign of how out of touch this administration is with the faculty, how little consultation and dialogue there’s been with the faculty,” Government professor Steven R. Levitsky said in an interview. “That’s why we’re so engaged.”

University spokespeople did not comment for this article.

After years of being seen as just another group in the campus dynamic, many faculty are pushing to be seen as something else entirely: partners. That growing discontent has already caused a reckoning, forcing both Garber and the Corporation to reevaluate how they work with faculty.

At the FAS town hall, Corporation Senior Fellow Penny S. Pritzker ’81 acknowledged criticisms that faculty were kept out of the loop. Pritzker wrote in a May 18 emailed statement that the University is “exploring ways for the Corporation to hear more directly from the faculty.”

And, Garber has been more responsive to faculty members after Manning’s poor reception at the FAS meeting, per one senior faculty

member.

But many faculty members say these “ad hoc” communication channels in times of crisis aren’t enough. Faculty, they argue, deserve their own seat at the table where decisions are made — instead of finding out what happened after the fact.

“During the semester, not a week goes by without hearing one or two colleagues say ‘faculty governance’ — and they never say there is too much,” Classics professor Emily Greenwood said at a May 14 FAS meeting.

Now, they’re pushing for reform.

A group of prominent faculty has introduced proposals to consider a University-wide faculty senate — an elected decision-making body — and even those who oppose the senate proposals agree governance change is needed.

As faculty look to use both their individual and collective voices, Harvard has a big question to answer: what role should faculty play in running the institution?

Since Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack on Israel, the faculty — the University’s “sleeping giant” — have risen from its slumber. Several professors called this year the most involved the faculty have been in their 20 or more years here, a time that includes the FAS’ 2005 battle with then-President Lawrence H. Summers, which culminated in a no-confidence vote.

“I’ve always kept my head down when it came to campus politics,” said Levitsky, who was recently elected to the FAS Faculty Council, an advisory group for the FAS and its dean.

“This year has been new for me,” he added.

Bioengineering professor Kevin “Kit” Parker wrote in an email that he became involved in the faculty senate working group because he had long been upset with Harvard’s culture. These frustrations, for Parker, came to a head with the University’s recent crises.

“I want to build heart valves for kids, not screw around with University politics,” Parker wrote, echoing a sentiment shared by a number of his colleagues. “But by virtue of my position as a tenured faculty member, I have institutional responsibilities that require I put bandwidth into solving its problems and charting its course.”

While many faculty credit Harvard’s leadership crisis with spurring them to action, some of the groundwork was laid in advance.

In March 2023, a group of faculty members across the University — around 70 at the time — formed the Council on Academic Freedom at Harvard, a faculty group that aims to uphold ideals of free expression and promote discourse on contested issues.

While the group, now with more than

170 members, has made headlines for its statements and leaders’ actions, its main function for members has been an email list over which they discuss and debate campus issues, from Harvard’s selections for presidential task forces to faculty governance.

CAFH co-president Edward J. “Ned” Hall, a Philosophy professor, said CAFH was “the first time” he’s had “sustained dialogue with people from other schools.”

Despite this uptick in involvement, several faculty members feel Harvard lacks institutional foundations for faculty governance. Its existing structures are often criticized as too weak, and there is no central University-wide body at Harvard, unlike many of its peers.

Hall said he found his time on the Faculty Council, under former FAS Dean Claudine Gay, to be quite productive, though he noted that the body’s efficacy was very tied to how the dean sought to use it. It could easily be a “rubber stamp,” he said, as it lacked power as a standalone body.

The Council has suffered from low election participation and a lack of interest in running for its positions, per several faculty members.

An FAS spokesperson wrote in a statement that FAS Dean Hopi E. Hoekstra “is committed to amplifying faculty voices within our School governance structure.”

“Early in her tenure, she established a faculty committee to enhance meeting effectiveness and created new channels for faculty in-

put to reach the President and Fellows,” they wrote. “Dean Hoekstra’s proactive leadership ensures the views of FAS faculty are heard and valued at the highest levels of the University.”

It’s not immediately clear if a new governance structure could avoid the engagement issues that plague the FAS or if the current increase in involvement is sustainable. Levitsky, for instance, said he expects to return his full focus to teaching after the moment of crisis subsides.

Proponents of a faculty senate say a well-designed model could avoid these issues, though the formal planning has yet to begin.

Over the last few weeks, the idea of a faculty senate has picked up steam across the University’s nine faculties.

Since April 9, a group of professors — led by University Professor Danielle S. Allen — has worked to advance resolutions to form a faculty senate planning body through each school’s governing mechanism.

While the group’s memo called on the faculties to either elect delegates to the planning body or come up with a process for doing so by May 15, all nine faculties have yet to do so. Most will not reach a final decision before the fall semester.

The resolution to form a senate planning body has drawn vehement debate among the

Faculty of Arts and Sciences, who will vote on the motion through an email ballot starting this week.

Though the proposal enjoys support from many prominent professors like Allen and former FAS Dean William C. Kirby, its opponents have called it too reactive to the University’s recent controversies, the wrong vehicle for governance reform, and a threat to the FAS’ position as Harvard’s central faculty.

Dean of Social Sciences Lawrence D. Bobo, one of the proposal’s loudest critics, has argued that faculty members do not have the power to convene a senate with real decision-making power. He has instead argued that governance reform should happen within the existing system, saying instead that faculty need representation on the Harvard Corporation.

Meanwhile, German professor Peter J. Burgard — who explored the idea of an FAS-only faculty senate in 2012 — has said he will oppose any University-wide faculty senate motion. The body, he wrote in an email, would dilute the FAS’ influence and “weaken the core of the university.”

Bobo, Burgard, and University Professor Ann M. Blair ’84 have all made unsuccessful motions during FAS meetings aimed at killing the planning body resolution or delaying it until the fall. Still, the issue seems to be galvanizing the faculty. The FAS meetings where the faculty senate planning body has been discussed were among the best-attended of

the semester.

The University’s other eight faculties are moving forward on the proposal as well. The proposal has come up for a vote at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and the Harvard Divinity School, while a potential September vote is expected at the Harvard School of Public Health.

At the other schools, where formal processes have moved more slowly, proponents have formed subcommittees to lobby colleagues and host town halls to answer their questions.

“I’ve heard so far, there’s interest and support for the idea and the broad goals, but that they would need to understand the design,” Harvard Graduate School of Education professor Julie A. Reuben, who introduced the planning body resolution at HGSE, said.

The idea of a faculty senate, though, predates the University’s current climate — by half a century.

In 1972, a committee chaired by then-FAS Dean John T. Dunlop proposed a “University-wide Senate” composed of professors and students from across Harvard’s nine faculties.

The Dunlop committee’s report described Harvard as “more a confederation of independent faculties than a unitary institution,” with each school responsible for its own funding — a decentralized model that largely

A group of professors, including University Professor Danielle S. Allen and Council on Academic Freedom at Harvard co-president Edward J. “Ned” Hall, began circulating proposals to form a University-wide faculty senate. They called for increased communication from the University to faculty members, saying their “ad hoc” channels in time of crisis were insufficient.

Former Faculty of Arts and Sciences Dean William C. Kirby argued in a Crimson op-ed that the University was in need of governance reform. In his op-ed, he backed calls for a faculty senate, arguing that it was needed to advise both the president and the governing boards.

Later that day, the Faculty of Arts and Sciences met with members of the Harvard Corporation, the University’s highest governing board. During the town hall, members of the FAS pressed the Corporation on various matters of university governance and decisionmaking, including the question of a faculty senate — to which interim Provost John F. Manning ’82 responded with a skeptical tone.

Faculty at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and Harvard Divinity School discussed motions delegates to a University-wide faculty senate planning body at their faculty meetings, but the motions did not come up for a vote.

Dean of Social Science Lawrence D. Bobo urged his colleagues to shoot down the faculty senate proposal in a Crimson op-ed published the morning of the monthly FAS meeting. He argued that it would be unproductive and that other forms of governance reform were needed instead — like faculty seats on the Harvard Corporation, the University’s top governing board.

During the meeting later that day, Allen and other faculty members in the working group introduced a motion to elect FAS delegates to a University-wide faculty senate planning body. The FAS, after a contested debate, moved to hold a May 14 special meeting to make a decision on the matter.

At the special meeting, after a second debate, the FAS decided to conduct their vote on whether to elect delegates to a planning body via online ballot.

continues to this day.

But, the report concluded, when University-wide or cross-faculty issues did arise, they were typically decided by central administrators. In other cases, one faculty — particularly the FAS — would set the de facto precedent. That, the report argued, meant policy decisions were made “without opportunity for the affected Faculties to discuss or consider the question.”

The solution it prescribed? A faculty senate.

Like the authors of today’s proposal, the Dunlop committee vested the authority to constitute their proposed senate in Harvard’s University Statutes, which grant power to a “University Council” consisting of Harvard’s entire professoriate. The Council has not met since the early 1900s; the Dunlop reports described it as “moribund” and “dormant.”

Over fifty years later, however, the University Council still has not awakened, and the Dunlop proposal never came to fruition.

But Government professor Theda Skocpol said she did not think the present moment lived up to the past.

“I would not say that the social ties and the ongoing conversations and thinking about what to do are there, anywhere near the way it was during the 1960s crisis — which was happening just as I arrived as a graduate student — or in the periods around Larry Summers’ presidency,” she said.

Without consistent engagement and strong lateral ties across Harvard’s faculties, Skocpol said she thought a faculty senate “would create an easily ignorable set of new titles on paper.”

Though the proposal has drawn impassioned debate, what a faculty senate would actually look like remains an open question. According to its proponents, that’s by design: The proposal’s authors say they want an elected planning body, not a self-selected working group, to sketch out possible constitutions.

Harvard Graduate School of Education professor Richard Chait, who studies higher education governance, said faculty senates usually fill two primary functions: “as a voice for faculty and as a means of self-regulation for academic matters.”

But the specifics of the proposal, including the senate’s role, may have to wait.

“At the end of the day, if the faculty and the University choose to have a senate, it has to be born through a highly consensual, expansive, consultative process,” Chait said. “I imagine they’ll have some modern-day equivalent of a constitutional convention in Philadelphia.”

Although a senate might be a revolutionary institution at Harvard, faculty senates are the norm among many of Harvard’s peer schools.

Northwestern University’s senate oversees faculty tenure and promotion policies, while Stanford University’s sets curricular requirements and research policy. Both senates regularly meet with top administrators and lay out principles of academic freedom.

Chait said he thought the greatest structural challenge to faculty senates is they are often not held accountable for the effects of their own recommendations. If a senate’s suggestions are implemented, he said, their success is accepted without fanfare; their failure, on the other hand, rarely backfires on faculty senators.

That lack of a feedback mechanism means, in turn, administrators and trustees may be less likely to take faculty recommendations seriously, Chait said.

But Reuben, the HGSE professor, was hopeful. A senate, she said, could bridge the gap between the highest echelons of Harvard’s governance and the faculty who see themselves as stewards of its core purposes: research and education.

“The most fundamental principle of shared governance is that the parts of the university that hold the knowledge and expertise should be primarily responsible for those parts,” she said.

tilly.robinson@thecrimson.com neil.shah@thecrimson.com

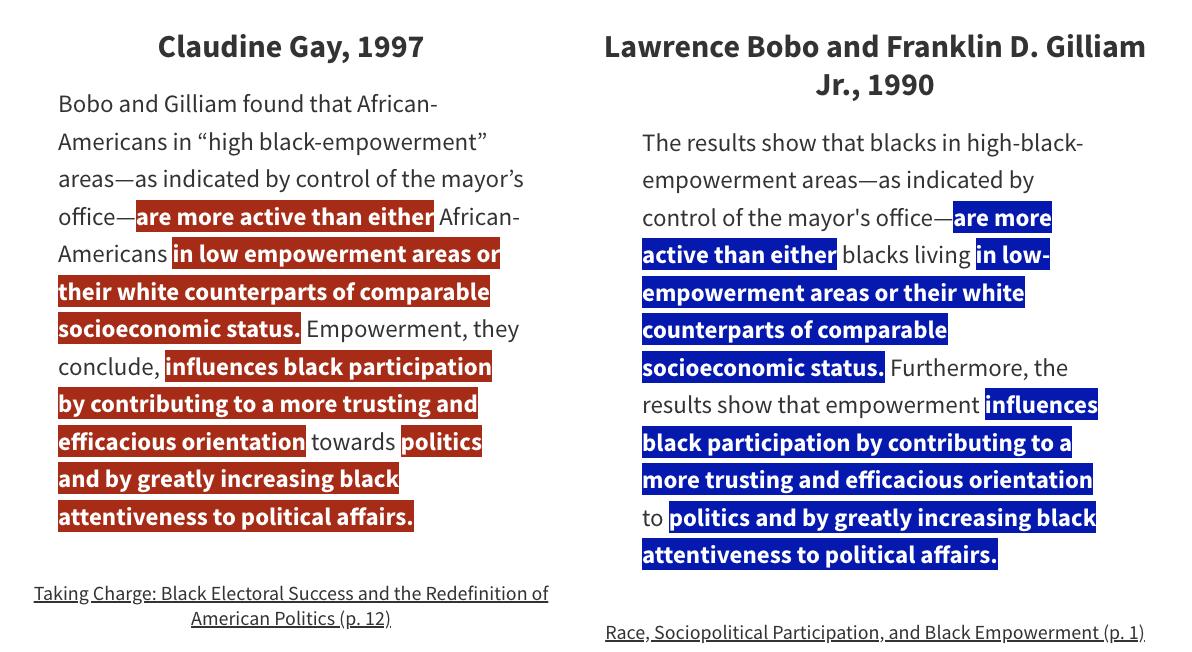

ALLEGATIONS. Harvard — already in the crosshairs of a conservative culture war — also came under fire for allegations of plagiarism against some of its top academics and administrators. With new software and unchecked scholarship at their disposal, conservative critics opened up a new frontier when they levied accusations against former Harvard President Claudine Gay.

Claudine Gay testified before Congress in order to defend Harvard’s handling of campus antisemitism. She faced considerable backlash for her remarks, during which Gay gave a noncommittal answer when asked if calling for the genocide of Jews would violate policy. She later apologized for her testimony.

Right-wing activist Christopher Rufo wrote in a post on X that he and journalist Christopher Brunet had waited “for the precise moment of maximum impact” before publishing, saying that “there are rumors that the plagiarism scandal could be the final nail in Gay’s coffin” — referring to the potential end of her presidency.

Aaron Sibarium of the Washington Free Beacon reported on additional allegations of plagiarism against Gay — across her dissertation and three of her other published papers.

The Harvard Corporation announced that they found Gay had not committed research misconduct, but that she would be “proactively” submitting four corrections across two of her published articles. The New York Post published a story with additional instances of alleged plagiarism in one of Gay’s articles.

The House Committee on Education and the Workforce expanded the scope of its congressional investigation into Harvard to include allegations of plagiarism against Gay.

The Harvard Corporation released a review that found that Gay had not committed academic misconduct. The Corporation also announced that Gay would make three additional corrections — this time to her Ph.D. dissertation.

Gay stepped down as Harvard president, with interim President Alan M. Garber ’76 taking her place.

Gay published an op-ed in the New York Times, calling the attacks on her scholarship illogical and racially motivated. She wrote that she stood by the findings of her scholarship.

By ANGELINA J. PARKER AND NEIL H. SHAH CRIMSON STAFF WRITERSPlagiarism is a cardinal offense for academics. In December, it also became the latest cudgel in the conservative culture war on Harvard and diversity, equity, and inclusion.

The development could not have come at a worse time for the University. Harvard was struggling to navigate public fallout from former President Claudine Gay’s now-infamous congressional hearing. The University was under a national microscope like never before, and politicians, alumni, and Harvard affiliates were calling for Gay’s resignation.

And amidst it all — as the Harvard Corporation met to discuss Gay’s future at the University — right-wing activist Christopher F. Rufo and journalist Christopher Brunet hit publish on a piece that would add a new element to the controversy: allegations that Gay had plagiarized large sections of her Ph.D. dissertation at Harvard.

The report was timed to make waves. Rufo, a prominent critic of critical race theory, boasted on X that their timing had been intentional. They had the tip for about

a week, he wrote, and held it till “the precise moment of maximum impact.”

Rufo’s report was quickly followed by an article by Aaron Sibarium in the right-leaning Washington Free Beacon, which unearthed additional allegations spanning Gay’s academic career.

The duo — Rufo and Brunet — had successfully hijacked the conversation, expanding a ballooning national scandal over antisemitism at Harvard to include both Gay’s academic credentials and the school’s diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts, which they said were to blame for Gay’s presidency.

The Corporation, backed into a corner, could not ignore the new attacks. After a review of Gay’s work, they said that though Gay would submit seven corrections to add citations across her dissertation and published works, they found that she had not committed academic misconduct.

“Never did I imagine needing to defend decades-old and broadly respected research, but the past several weeks have laid waste to truth,” Gay wrote in a New York Times op-ed shortly after her resignation. “Those who had relentlessly campaigned to oust me since the fall often trafficked in lies and ad hominem insults, not reasoned

argument.”

But despite Gay’s defenses, in the public’s eyes, the damage had been done. Gay was pushed to resignation to the delight of Harvard’s most outspoken antagonists, Rufo included.

“Today, we celebrate victory. Tomorrow, we get back to the fight,” Rufo posted to X the day of Gay’s resignation. “We must not stop until we have abolished DEI ideology from every institution in America.”

Harvard had already found itself in the crossfires of the culture war. But with new software at their disposal and a trove of unscrutinized scholarship to dive into, the plagiarism allegations against Gay had opened up a new frontier.

The allegations might have ended with Gay’s sudden resignation. Instead, they took off.

The first three months of 2024 saw three more Black women at Harvard hit with anonymous plagiarism complaints, one after another: Chief Diversity Officer Sherri A. Charleston, Harvard Extension School administrator Shirley R. Greene, and Sociology professor Christina J. Cross.

As the allegations poured in, Rufo crowed on X about how the allegations discredited scholarship on race and diversity, what he called “grievance disciplines.” But some academics and experts said the string of complaints elide important distinctions between downright plagiarism and sloppy writing or even standard academic practices.

— who has studied what it means for academic writing to be original — said she felt that using line-by-line plagiarism checks to determine the academic integrity of faculty work was “a little bit like using kindergarten criteria to evaluate people who are experts at knowledge production.”

Charleston was accused in January of lifting several phrases in her 2009 Ph.D. dissertation. In many of the alleged cases, she cited the relevant author but did not use direct quotations, while in others the complaint alleged no citation.

was largely shot down by academics. The Sociology department published a statement defending Cross’s work, and several academics in charge of large public datasets said her use of standard descriptions was “simply good research practice,” not plagiarism.

“We find these bogus claims to be particularly troubling in the context of a series of attacks on Black women in academia with the clear subtext that they have no place in our universities,” the Sociology department wrote.

Jan. 29, 2024

Sibarium reported in the Washington Free Beacon that an anonymous complaint filed to Harvard’s Office of Research Integrity had accused Harvard’s chief diversity officer Sherri A. Charleston of plagiarism.

Feb. 12, 2024

The Crimson reported that an anonymous plagiarism complaint had been filed to the University against Harvard Extension School administrator Shirley R. Greene.

Mar. 18, 2024

Harvard Medical School assistant professor Dipak Panigrahy was accused of plagiarizing large portions of an expert report on possibly carcinogenic chemicals in a class action lawsuit against Lockheed Martin from works by the International Agency for Research on Cancer.

Mar. 22, 2024

Rufo reported that Harvard Sociology professor Christina J. Cross had been accused of plagiarism in an anonymous complaint filed to the Office of Research Integrity.

Mar. 24, 2024

Colleagues rallied to defend Cross, writing that the complaint made baseless allegations against her. The Harvard Sociology Department, as well as several other prominent groups of sociologists, issued statements in her defense.

Apr. 9, 2024

An analysis published in Science Magazine accused Harvard Business School professor Francesca Gino of multiple accounts of plagiarism, compounding existing allegations against her of data misconduct.

Today, we celebrate victory. Tomorrow, we get back to the fight. We must not stop until we have abolished DEI ideology from every institution in America.

Christopher F. Rufo Conservative Activist and JournalistThe complaints filed against Gay, Greene, and Cross, for example, did not contend with the papers’ findings. Rather, they scrutinized their definitions, methodological descriptions, and prose. Sociology professor Michèle Lamont

A paper she co-wrote with her husband LaVar J. Charleston and Jerlando F.L. Jackson was also accused of reusing interview content and findings from a prior paper by her husband.

Greene faced allegations of lifting language from several other scholars, in most but not all cases citing the relevant scholar but not including quotation marks. A plagiarism expert consulted by The Crimson at the time said the complaint contained several frivolous allegations but that there were some warranting further review.

In Cross’s case, the most severe allegations reference public dataset or methodology descriptions — and the complaint

All three have not commented publicly on the allegations. The University has repeatedly said it would not comment on specific cases, citing the ongoing review processes.

The journalists amplifying the complaints said that the scholars — particularly Gay — violated the Harvard College Writing Program’s Harvard Guide to Using Sources, an online resource for undergraduates engaging in academic writing. The guide states that all language used from other scholars must either be paraphrased and cited or directly quoted and cited.

In a Dec. 31 Crimson op-ed, an anonymous Harvard College Honor Council

Apr. 12, 2024

FAS Dean Hopi Hoekstra addressed the anonymous plagiarism allegations against Harvard affiliates and condemned attacks on identity. She declined to comment on the ongoing review processes, citing her involvement.

May 2, 2024

In a town hall with the FAS, Harvard Corporation Senior Fellow Penny S. Pritzker ’81 appeared to acknowledge the string of anonymous plagiarism allegations, saying it was “not lost on” the Corporation that there was a “pattern of attacks” on “women of color.”

ELIAS J. SCHISGALL — CRIMSON STAFF WRITER

ELIAS J. SCHISGALL — CRIMSON STAFF WRITER

member argued that plagiarism complaints similar to the one filed against Gay “often” lead to year-long suspensions for undergraduates.

“There is one standard for me and my peers,” they wrote, “and another, much lower standard for our University’s president.”

But Lamont said that scholarship produced by faculty should not be conflated with that of students. Faculty research integrity is regulated by a different policy: the Interim Policies and Procedures for Responding to Allegations of Research Misconduct, which the Corporation said Gay had not breached.

“The kind of work we produce has nothing to do with the term papers that undergrads produce,” Lamont said, comparing the standards for students and faculty. “I mean, what they’re doing is super important in their own apprenticeship but that’s not what research is about.”

Lamont argued that Harvard — and other institutions — need to clarify differences between the policy for faculty members and undergraduates to ensure that policies are tailored to the levels of expertise of each group.

“I think if universities take very firm

stances to defend their faculty, certainly this may contribute to delegitimizing these attacks,” she said.

Typically, leveling an allegation of plagiarism is supposed to defend the scholarly record and the contributions of the allegedly plagiarized author. But from the get-go, Rufo emphasized that his aims were much bigger.

“Let’s talk prestige, scholarship, degrees, DEI, affirmative action. Let’s have a full-blown plagiarism war,” Rufo posted to X shortly after Gay’s resignation. “The more attention focused on elite academia, the more people will see the incompetence, the psychopathologies, and the ideological rot.”

He ended his post with an unambiguous call to action: “Accelerate!”

And accelerate they did. Both Rufo and Sibarium have made plagiarism complaints against DEI administrators or researchers into a kind of miniature beat, expanding their focus beyond Harvard to academics and administrators at MIT, the University of California, Los Angeles, and Columbia

University.

At Harvard, the fixation on Black female scholars who study issues of race and equity has led many academics to criticize their reporting as racially motivated.

Jennifer L. Hochschild, a political scientist at Harvard from whom Gay was accused of plagiarizing, said the string of allegations suggested a “targeted” attack on Black women in service of the conservative push to discredit institutions of higher education and DEI initiatives.

“There’s obviously a highly selective, very targeted attack on precisely the people who are most vulnerable, who have traditionally historically forever been most vulnerable, who represent what a very large proportion of the country resents, fears, envies, mistrusts. The combination of race and gender and high status is a very volatile one,” said Hochschild.

Hochschild previously faced backlash for saying Rufo had misrepresented his masters degree from the Harvard Extension School in comments that were perceived as belittling HES students. She later apologized for her remarks.

Rufo has rejected the notion that his work has racial motivations, as have Sibari-

um and Brunet. Still, he was startlingly candid about the demographics of those he had accused.

Rufo wrote in a post on X that a source of his had “investigated white social-justice scholars at Harvard, but did not find pla-

There’s obviously a highly selective, very targeted attack on precisely the people who are most vulnerable, who have traditionally historically forever been most vulnerable,

JenniferL. Hochschild

Harvard Government Professorgiarism in their work” — suggesting Black scholars could be more likely to plagiarize.

In response to a request for comment for this article, Rufo wrote that his source had “ran some of Professor Hochschild’s papers through the detection software and did not find any plagiarism.”

“So, in a real way, she herself is responsible for the plagiarism disparities within

Harvard’s African-American studies faculty,” Rufo added.

Hochschild responded by saying she was “delighted that Mr. Rufo’s helpers found no plagiarism in my writings,” adding that she had no further comment.

To Sibarium, the initial set of allegations against Gay was “frankly, just a compelling story on its own terms.” But he also could not ignore the trend.

The “common thread here is DEI,” Sibarium said. The identity of those accused, he added, followed a trend because it is “more a function of the composition of DEI officers than anything else.”

Brunet said he found the original tip and brought it to Rufo while he was reporting on academic fraud.

“I think the plagiarism speaks for itself,” Brunet said, referring to Gay’s corrections. “I’m just an academic scandal guy and sometimes race gets caught up there.”

That the allegations targeted DEI administrators and scholars of race was, to Brunet, simply an ironic illustration of the intellectual bankruptcy of liberal institutions.

It’s “funnier than if a biology professor got hit, or if a physics professor or an English professor,” Brunet said. “They’re not real scholars. It’s a fake profession to begin with. So, when it’s fake and plagiarized, it makes it double funny.”

Sibarium separated his reporting from Rufo’s ongoing campaign against DEI, instead offering a conjecture about Rufo’s motivations. Rufo, he argued, “latched onto” plagiarism allegations “as a powerful weapon” because “the plagiarism allegations provide an almost objective referee in the culture war.”

Brunet said that he felt “conservatives have a duty to weaponize” plagiarism allegations “as much as possible.”

“Liberals would be weaponizing it as much as possible, if they could,” he said.

Hochschild likewise said plagiarism allegations were simply the most novel tool in a much longer ideological tradition.

“This is just, in some ways, another manifestation of the same old same old American political culture around race, gender and class. Very effective,” Hochschild said. “Christopher Rufo and his allies are really good at what they do.”

Plagiarism and academic dishonesty scandals are nothing new. In the 1980s, a falsification crisis hit the life sciences as researchers were under increased pressure from universities and biopharma companies to show significant results, while the 2010s

saw the rise of the replication crisis in social psychology.

But while previous research controversies mostly played out in university halls and the pages of academic journals, the current string of academic misconduct complaints has a distinctly public nature, bolstered by the ubiquity of software like Turnitin and other, artificial intelligence-powered plagiarism detection tools.

With such a low barrier to entry for alleging plagiarism, some academics said, anyone — regardless of expertise — can make career-altering accusations against scholars, whose fate may largely be decided on social media before any technical review process is even conducted.

Lamont, the expert in original scholarship, challenged the integrity of plagiarism allegations that have been made online, saying that “these criticisms are produced by people who have zero understanding of what research is about.”

Ruben Enikolopov, chairman of the Board of the Review of Economic Studies, similarly agreed that making academic data widely available online has caused the overall quality of checks on academic integrity to deteriorate.

“We realized that this crowdsourcing is a low bar, and we have to push it higher and introduce our own data editors to make sure that everything is kosher,” said Enikolopov.

But Brunet, the journalist who reported on Gay, offered a counterpoint: institutions’ reviews are “so broken,” he said, that

“there’s no other choice than to play it out in the public arena.” Brunet argued that schools are biased actors, with “every incentive to sweep” allegations against faculty and administrators “under the rug.”

Government professor Theda Skocpol, a former dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, said she believes universities need to review how they’ve dealt with high-profile plagiarism cases in the past and then determine an effective process to use going forward.

“I know some very prominent people who are still on the faculty were accused. It’s not as if people said, ‘Oh, no, we’re not going to look at this.’ It’s also not as if they were fired,” Skocpol said. “That’s the kind of process that we should have and we need to have it ready now.”

“High profile people are going to be like sitting ducks for externally motivated actors in the current period,” she added.

In January, a few weeks after Ackman — the billionaire and former donor — helped promote the allegations against Gay, Business Insider published an exposé on his wife Neri Oxman, formerly a professor at MIT. Ackman called the move retaliatory and vowed revenge in a post on X, saying he would launch AI-powered plagiarism reviews of faculty members at MIT and its peer schools.

“Why? Well, every faculty member knows that once their work is targeted by AI, they will be outed,” Ackman wrote.

“No body of written work in academia can survive the power of AI searching for

missing quotation marks, failures to paraphrase appropriately, and/or the failure to properly credit the work of others,” he added.

Harvard Kennedy School professor Sheila S. Jasanoff ’64 cautioned against plagiarism reviews like the one Ackman had proposed, noting that software could often mistakenly flag scholarship as having been plagiarized.

“The statistical tools, though very powerful, may be in the business of over-detecting, creating false positives in a way that the older cases did not actually allow for,” said Jasanoff.

And four months later, Ackman’s proposed plagiarism review has made no public progress. The news cycle, Ackman, and others interested have moved to more contemporary issues, such as the wave of pro-Palestine encampments that have emerged at universities across the country.

While the threat of such reviews — and their subsequent politicization — looms larger than ever, Brunet said he believes plagiarism stories don’t have much left in the tank.

“I see the public getting tired of it eventually,” Brunet said.

“I think there’ll be one big wave eventually and maybe continued stories here or there, but I don’t think it’s going to be a consistent theme for the next five years,” he added.

angelina.parker@thecrimson.com neil.shah@thecrimson.com

FUNDRAISING. As the University prepares for a long-term downturn in giving, interim Harvard President Alan M. Garber ’76 is leading the charge to woo back disillusioned donors. Still, the current drop in donations could be felt for years to come.

Harvard’s initial response to Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack on Israel infuriated many of the University’s major donors, but during the first weeks of the donor revolt, senior leadership remained optimistic that it could quickly win them back.

But after seven months of fallout, senior administrators and members of Harvard’s governing boards concede that the impact of the current drop in donations will likely be felt for years to come.

As the University prepares for a longterm downturn in giving, interim Harvard President Alan M. Garber ’76 is leading the charge to woo back disillusioned donors.

Under the direction of Garber and Vice President of Alumni Affairs and Development Brian K. Lee, gift officers and other senior administrators have been “working like dogs” to reverse the backlash, one donor said. Meanwhile, Harvard’s development office has shifted its outreach strategy as it speaks with donors amid the ongoing campus controversy.

Instead of focusing their time on recruiting new pledges, development officers have gone into listening mode, trying to salvage relationships with the longtime donors who have expressed deep concern with the University’s leadership in recent months, according to three people familiar with the office’s efforts.

Lee acknowledged in a statement that “this has been a challenging year for Harvard and for many who care deeply about Harvard.”

“We are constantly engaging with our alumni and donors, hearing their feedback and sharing updates from campus — that is true this year, as it has always been,” Lee wrote. “They do not always agree with us, and they do not always agree with each other, and they do not speak with one voice — but they are important members of our university community.”

Some of Harvard’s biggest donors have publicly paused donations to the University in the months since October, saying future gifts are conditional on the administration’s handling of antisemitism on campus.

The Wexner Foundation and Israeli billionaires Idan and Batia Ofer cut ties with the Harvard Kennedy School just weeks after Oct. 7. Leonard V. Blavatnik,

While Griffin left open the possibility for future contributions, he has not shifted his stance yet. In a May 11 interview with the Financial Times, Griffin urged

We are constantly engaging with our alumni and donors, hearing their feedback and sharing updates from campus — that is true this year, as it has always been.

Brian K. Lee Vice President of Alumni Affairs and Developmentwho had previously donated $270 million to Harvard, including $200 million to Harvard Medical School in 2018, decided to pause donations in December.

Harvard megadonor Kenneth C. Griffin ’89, who has donated upwards of $500 million, followed suit in January.

Harvard to “embrace Western values” and listen to donors.

“Many wealthy donors have valuable insight into transformation and improvement strategies that are clearly needed at this time,” he said.

A spokesperson for Griffin declined

to comment on whether he had met with Garber recently or reconsidered his pause on donations. A spokesperson for Blavatnik did not respond to a request for comment on whether he is still pausing contributions.

While some donors have made their concerns public, many more have privately told development officers and senior Harvard administrators that they either wanted to pause donations or were considering doing so.

One Kennedy School donor previously pledged to donate roughly $15 million over a 15-year period but has now stopped less than halfway through the pledge period, according to a person familiar with the gift.

Another prominent donor cited a perceived double standard in the way the administration has handled antisemitism compared to other forms of hate speech in their decision to halt future giving.

“We are most definitely stopping any new grants, any new giving,” the donor said. “We hope we can come back, but we’ll

nate an amount “well into the seven figures” — said he would not contribute over concerns that Harvard had not done enough to condemn Hamas and support Jewish affiliates on campus.

“Unless there’s a very clear moral stand by the organization, that is not kind of politicking and ‘two sides of the issue,’ there is zero chance that I will donate,” he said.

In December, estimates of FAS annual giving showed at least a 16 percent drop in donations from the prior year, according to a person familiar with the situation.

At a closed-door town hall in April, Penny S. Pritzker ’81, Senior Fellow of the Harvard Corporation — the University’s highest governing body — acknowledged that

Harvard President Claudine Gay’s resignation in Janu -

Less than three months after assuming office, Garber flew to London to meet with donors and alumni, speaking to a room of over 200 at an event co-hosted by the Harvard Club of the United Kingdom and the Har -

Victoria W.K. Leung ’91, president of the Harvard Club of the UK, wrote in a March statement that Garber “addressed the challenges head-on” during his meet-

“I think many were pleasantly sur -

After the UK trip, Garber and several HAA members visited Miami. In Florida, Garber met with alumni and donors for small-group and one-on-one conversa -

He has been on the road and on the phone speaking to very angry donors and beginning to lower the temperature. No one is doing more than Alan Garber to address this issue and he’s been doing it very effectively.

M.

Harvard Corporation Membertions. While traveling, Garber acknowledged that donations were down after Harvard’s tumultuous fall semester.

Garber also visited the nation’s capital in mid-April, where he addressed a crowd of 500 alumni at an event co-spon -

As interim president, Garber is also now the University’s interim chief fundraiser — a role that he has fully embraced since former

sored by the Harvard Club of Washington, D.C. Peter J. Solomon ’60, who served as the Chairman of the Friends of the Center for Jewish Studies for 45 years, said he felt Garber’s administration has been more receptive to alumni concerns, compared to Gay’s administration last fall.

“I reached out to the senior levels of Harvard, and I did not find them forthcoming frankly, at the period,” Solomon said. “And I didn’t reach out to them as a donor. I reached out to them as somebody who has been involved in almost every level at Harvard, except on the Corporation, over 60 years.”

Solomon and other donors said they’ve had a quicker line to top administrators since the start of Garber’s tenure.

Solomon said that he had spoken with Garber in the last few weeks, including when Garber attended a dinner at the Faculty Club held to mark Solomon’s retirement as chairman, saying he was “very impressed” by Garber’s leadership so far.

Garber has also been “meeting furiously” with donors in private conversations and phone calls, a person with knowledge of Harvard’s fundraising efforts said.

At a faculty town hall in April, Corporation member Shirley M. Tilghman touted Garber as Harvard’s “biggest strength in managing fundraising,” according to meeting notes shared with The Crimson.

“He has been on the road and on the phone speaking to very angry donors and beginning to lower the temperature,” Tilghman said. “No one is doing more than Alan Garber to address this issue and he’s been doing it very effectively.”

Outgoing Harvard Treasurer Paul J. Finnegan ’75 echoed Tilghman in a May 16 interview, emphasizing Garber’s role in mitigating donor fallout.

“The presence of Alan Garber has been just extraordinary in terms of changing the narrative,” Finnegan said. “He’s reached out to donors and alums, internationally and explained what his plans are to deal with various challenges on campus.”

“Longer term, I personally feel that people will come to appreciate what Alan and the team have done, and are doing, to help Harvard navigate the challenges it faces today,” Finnegan added.

Behind the scenes, Harvard has been adjusting its strategy.

One person who is involved in Harvard’s fundraising efforts said that development staff have told alumni fundraisers to be sensitive and understanding — and not to push too hard. Development

Francisco, and New York, where they were joined by Harvard College Dean Rakesh Khurana.

Since then, Claybaugh and Dunne have continued to meet with donors for Zoom conversations and other events.

Stephen W. Baird ’74, a longtime Harvard donor, said he was a “little surprised” when Khurana flew to see him in the fall in Chicago, because he didn’t con -

March interview that the FAS’ civil discourse initiative has drawn particular enthusiasm.

“I think this is really important work, to be able to tell our Harvard story, and all the exciting research and scholarship and education that we’re doing on campus, that we’ve always done and continue to do,” Hoekstra said. “That’s an important message to share with our alumni and

launch a campaign without confidence that it can secure major multi-million dollar gifts from loyal donors or a permanent president in Massachusetts Hall who would be able to see the campaign through from start to finish.

Still, Harvard is increasingly dependent on philanthropy to support its initiatives.

Between fiscal year 1998 and fiscal year 2023, the proportion of Harvard’s

The presence of Alan Garber has been just extraordinary in terms of changing the narrative.

Ougoing Harvard TreasurerCoughlin, a senior strategy manager at Harvard’s Office of Financial Strategy and Planning, told the Harvard Graduate Council in a November presentation that the University is “more philanthropy dependent, which does present a risk when you think about the volatility of the market, or a downturn in retention.”

Even though gifts make up a relatively small fraction of annual revenue at each of Harvard’s schools, they play an outsize role in supporting discretionary spending and allowing flexible budgets.

In a Nov. presentation to the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Scott Jordan — the school’s dean of administration and finance — told faculty that current-use gifts were “important to the FAS” because they were largely unrestricted and available for use by the dean.

Three people involved in Harvard’s fundraising efforts said they thought donors who fund specific institutes or research projects are less likely to cut ties over broader concerns about Harvard’s campus climate or handling of pro-Palestine protest. Contributions to unrestricted funds, though, might take a larger hit.

Along with doubts from long-time donors, Harvard also faces the uphill challenge of convincing younger alumni to donate, according to four people with knowledge of Harvard’s fundraising efforts.

Younger classes often have lower participation rates in annual giving. In 2023, Harvard suspended its annual Senior Gift Fund, which had been long plagued by low participation.

While multiple people with knowledge of Harvard’s fundraising said that philanthropy has dropped over the past seven months, the overall numbers remain in flux. Contributions typically spike in Dec., due to tax filing considerations, and in May, when alumni

flock back to Cambridge for reunion events.

Some alumni fundraisers said they’ve had success in their efforts to raise money amongst classmates despite the turmoil of the past year.

Paul H. Barry, who helps encourage alumni philanthropy at the Harvard Business School, wrote in an emailed statement that “fundraising at HBS continues to be robust.”

Barry added that he plans to continue giving and will encourage his classmates to do the same.

Meanwhile, giving to the Harvard Kennedy School Fund — which collects alumni donations — is almost half a million dollars higher in fiscal year 2024 than it was at this point in fiscal year 2023, although the fund is extremely small in comparison to the Harvard College Fund.

That may indicate a divide among Harvard’s alumni base — between contributors with an undeterred loyalty to Harvard and their own fond memories, and those whose frustration over recent events has driven them away from the University until they see change.

The slowdown in giving is not immediately an existential threat to Harvard, a school with the largest endowment in American higher education and an unparalleled brand name.

Still, the University currently faces strong political headwinds amid a congressional investigation into antisemitism on campus. If lawmakers attempt to limit Harvard’s federal funding, it will feel the loss of trust from many of the University’s most loyal backers all the more acutely.

“Institutions like Harvard are easier to tear down than they are to build,” Solomon said.

emma.haidar@thecrimson.com tilly.robinson@thecrimson.com

VACATION. Several student organization at Harvard College boast international conferences that rake in money, providing a profitable funding stream. But while these conferences hold the promise of unparalleled educational experiences for attendees, some club members say the pedagogical motives take a backseat to the opportunity to travel the world for free.

When Oscar Yang, a high school student who attends an international school in Shanghai, signed up for The Harvard Crimson’s Crimson Journalism Camp in 2023, he saw it as a unique chance to “try something new.”

“There’s very few opportunities in China where you can really do journalism practice,” Yang said, though he wrote in an emailed statement he was “not aware” that the program was not officially Harvard-run.

Yang is one of the thousands of high school students who have participated in conferences hosted by Harvard clubs in over a dozen countries abroad, from Australia to India to Panama.

For students like Yang, conferences hosted by clubs that bear the Harvard name can seem like rare and prestigious opportunities, especially if they don’t realize the conferences are not actually facilitated by the University.

But in exchange for a chance to learn from Harvard undergraduates, these conferences often cost students hundreds or even thousands of dollars to attend — and cater to students from wealthier backgrounds.

As Harvard clubs have grown into full-fledged companies with six-figure budgets, some of them have come to rely on international conferences as a significant source of revenue.

These international conferences promise to provide unparalleled educational experiences to students across the globe. But for some club members, this pedagogical mission takes a back seat.

Instead, the international conferences serve as an opportunity to travel the world for free, and, in some cases, indulge on the dime of the Harvard name.

In his sophomore year, Daniel J. Ennis ’25 — treasurer for the Harvard International Relations Council, an umbrella organization for international conferences — staffed a Harvard National Model United Nations conference in Panama. After it was over, he and the other Harvard students stayed in the country to do a liquor tasting, try the local cuisine, and explore different towns.

“It was super appealing to me,” Ennis said. “It really bought me in, and that’s why I did it as a junior.”

Post-conference experiences like this one, he said, are “basically a vacation for

the staffers.”

At each international conference, the budget often covers the expenses for flights, hotel fees, transportation, and related costs for dozens of staffers. In exchange for working at the conference, Harvard students receive an all-expenses-paid round-trip flight to a foreign destination — and a potential bonus vacation.

These post-conference trips are funded by the profits of the conference, according to Ennis.

“We either stay in the country or we go to a nearby country,” he said. “The first couple of days are kind of just relaxing and taking a break from the hectic life that is at the conference, and then a few days of doing different cultural immersion stuff.”

Theo J. Harper ’25, who ran the finances for HMUN India 2023, said that con -

ferences are “primarily set up to make staffers happy,” adding that within the IRC, the opportunity for travel serves as a “rewards mechanism.”

I never had an opportunity to travel as much as I am now, especially being able to serve a community that I grew up in.

I. Chowdhury ’25 HMC Middle East PresidentHarper unsuccessfully sued the IRC earlier this year after he was temporarily removed for redirecting $170,000 of the group’s income to an unofficial bank account. He called the move a “financial stress test” to expose the organization’s financial security flaws and a lack of transparency from the board.

“There’s no educational experience. The incentive is you get to travel — so you get to go to a foreign country — and the incentive is you get a post-con,” Harper said. “For example, in Africa, that postcon was a safari. In Latin America, we went to lay on a beach in Panama. In India, we went touring around the Taj Mahal.”

Harvard Model Congress Asia President Stephen G. Norris ’25 said that he traveled to Thailand, the Philippines, Singapore, and Japan during HMC Asia’s post-cons in past years.

“The opportunities for travel are unmatched, in my opinion,” he said.

The chance to visit other countries is especially significant for low-income students who otherwise would not be able to afford such travel.

HMC Middle East President Nabila I. Chowdhury ’25 said HMC was the first time she had left the country without her family as a first-generation, low-income student.

“I never had an opportunity to travel as much as I am now, especially being able to serve a community that I grew up in,” Chowdhury said.

Still, some maintained that the experiences of the student attendees was the priority during conferences.

IRC president Annabelle H. Krause ’25 said the organization’s primary goal was to bring Model UN to students around the world and educate delegates as well as undergraduate staffers.

“These conferences are a lot of work for both our boards and our directors,”

she said.

“I don’t think it’s fair to characterize it as a free trip,” she added.

Vivian Yee ’25, Secretary-General of HNMUN, concurred.

“It’s by no means an easy trip to another country,” she said.

Beyond what they bring to individual undergraduates, international conferences also have become immensely valuable for the organizations that host them.

In the face of meager funding from the Harvard Undergraduate Association, several organizations have come to rely on profits from conferences to allow them to be self-sufficient. In 2020, for example, the IRC reported more than $700,000 in revenue and $1.2 million in net assets on their tax forms.

While Chukwudi Michael “Chudy” Ilozue ’25, the secretary general of HNMUN Africa, said his conference was “not primarily a money seeking opportunity,” other staffers stressed the international conferences’ financial significance.

Yee said that though the educational mission of HNMUN plays a part in its role, in some sense “the conferences are our primary revenue generating functions.”

According to Harper, HMUN India 2023 was “immensely financially successful,” with a “turnover of well in excess of half a million dollars” and a profit of around $130,000.

Krause and Ennis denied Harper’s estimates of the revenues from HMUN India, though they did not provide their own estimates, citing confidentiality agreements in contracts with partners.

Harper also said that HMUN India was largely successful because the organization bought out a block of hotel rooms in bulk at a discounted price, then charged students a “small markup” on that price as part of their overall delegate fee. Ennis also denied this.

“I don’t think it’s fair to say specifically the hotel rooms specifically are marked up,” he said.

Yet ultimately the conferences’ profits — which come from the delegate fees collected from the participants, as well as corporate sponsorships — rely largely on the number of participants and their ability to pay the fee.

Ennis said that while the majority of the IRC’s profits come from its domestic conferences, the international conference delegate fees enable funding for the

competitive traveling team’s activities, social events, and philanthropic programs.

Norris noted that because just a fraction of HMC’s revenue comes from the HUA, the monetary value of the conferences “absolutely does hold some weight.”

He added that the self-sustaining nature of the conferences was both “a blessing and a curse” that allowed the board financial flexibility but could also “cloud some of our judgment.”

Several members of Harvard clubs that host international conferences said that the events typically attract a very particular set of attendees: students from prominent high schools with the wealth to pay for the experience.

Aspen L. Abner ’24, who will organize HMUN China 2024, said that because the conference’s advertising is typically in English, participants tend to be English speakers from international private schools in affluent urban centers.

Abner pointed to registration fees — which are around $529 — as a possible reason for the skew.

Harper said that when HMUN Australia was created, it was “explicitly pitched” as a conference that would “rely financially on Australian private schools be -

HAUSCR Summit for Young Leaders in China Beijing, Shanghai, and Hangzhou

China Thinks Big Shanghai

Harvard Model United Nations Australia Sydney, Australia

HMUN China Guangzhou, China

HMUN Dubai Dubai, the United Arab Emirates

HMUN India Bengaluru, India; Delhi - National Capital Region, India

HMUN Latina America Panama City, Panama

There’s no educational experience. The incentive is you get to travel — so you get to go to a foreign country — and the incentive is you get a post-con.

Theo J. Harper ’25 Member of HMUN Indiacause that’s the only way you can financially make that kind of thing work.”

IRC leadership, however, denied that the conference was pitched that way. They also noted that a local partner company handles marketing, advertising, and recruitment of delegates to conferences.

“I can’t speak to if our host team is specifically targeting Australian private schools. But our goal is not to target private schools to generate revenue,” Krause said.

To make travel and accommodations

HMUN Africa Nairobi, Kenya

Crimson Journalism Camp Korea, China, Indonesia, the United Arab Emirates

HARVARD UNDERGRADUATE FOREIGN POLICY INITIATIVE

Rotating Foreign Summit Rome, Italy; Istanbul, Turkey; Seoul, South Korea; Paris, France

less prohibitive for students, several of the international conferences offer financial aid for attendees.

For HMUN China this year Abner said she has introduced fee waivers to help recruit participants from “lower income areas.”

“I thought I could take some time to step out of my comfort zone, to join a program where I can connect with colleges — and of course, Harvard was a big name,” Yan said.

Now, Yan has come full circle.

ences to boost their resume, there are others who have real interest in global issues.

known around the world, really, for our directors being very good at what they do,” he said.

I thought I could take some time to step out of my comfort zone, to join a program where I can connect with colleges — and of course, Harvard was a big name,

According to Ennis, HMUN and HNMUN typically allocate 15-20 percent of their conference budget to their financial aid program — which includes waiving delegate fees or subsidizing hotel rooms or flights.

Yee said that this program is publicized in the conference policies, on social media, and among past participants.

According to Norris, as part of HMC Asia’s goal to reach “majority public schools in the Asia Pacific region,” the board sets aside around 10 percent of the conference budget for financial aid — upwards of $10,000 a year — to “really try and get as diverse a delegate base as we can.”

However, the amount of financial aid awarded to attendees is conditional on the overall financial success of the club and conference. And for some clubs, the financial aid program can be the first to take a hit when the conference doesn’t generate enough profits to cover all the costs.

Chowdhury said that securing enough funding for HMC Middle East’s financial aid program has been “difficult,” because the conference does not generate a profit.

She added HMC Middle East typically makes back just enough to cover the conference costs and flights and housing for staffers, though “we do try to at least give two or three students some financial aid money.”

In the summer after his freshman year of high school, Mike Yan ’27 attended a Harvard conference for high school students.

He is one of the staffers responsible for organizing the logistics of the Harvard Summit for Young Leaders in China — a ten-day conference organized by the Harvard Association for U.S.-China Relations.

Yan wrote in a text message that at the time, he did not know the conference was entirely student-run, but “kind of suspected it” when Harvard students — not professors — taught seminars to high school attendees.

Several staffers and conference directors said in interviews that the Harvard name — especially the value of the brand abroad — was a crucial factor in drawing attendees to the conferences.

Kyle E. Neeley ’26, a director for HAUSCR, called Harvard “probably the biggest or most widely known brand in the entire world.”

“Especially in mainland China, the name of Harvard holds a lot of weight,” he said.

The Harvard name also plays a role in helping some organizations — like the IRC — secure partnerships with companies based in countries abroad, who share a portion of the profits in exchange for staffing or advertising, according to Ennis.

“The Harvard name does bring us a long way — especially internationally, especially amongst high schoolers when it comes to recruiting — and I think partners see that and want to find a way to capitalize off of that,” he said.

He added that the

IRC’s contracts with partner companies are “zero-loss,” meaning the IRC avoids assuming any losses when their conferences are not profitable. Companies, in other words, trust HMUN or HNMUN’s reputation — and the Harvard name attached to them.

Yet students have more reasons to attend than mere prestige. According to Abner, though there is a “batch of students” who participate in confer -

Yan described his time at the conference in high school as “more of a resume padding experience,” but he said many of the high schoolers who he has since encountered as a staffer had different motivations.