37 minute read

Seeking Better Paths

Suffragettes toured the state’s northwest corner in 1911 to bolster support for voting rights.

affirmative side of the argument and was declared the winner by the judges. The subject of the debate was: “resolved that throughout the United States proper, full suffrage should be extended to women equal to that now enjoyed by men.” The Agora Society argued that a woman is man’s equal and that therefore she deserved the ballot, stating, “Women’s suffrage has been continually advancing and has met with success everywhere, as proved by figures from the Suffrage States and foreign countries where it has been tried and therefore as it is a right movement and proved successful and practical, there is no reason why women should not have the ballot, and therefore it should be given to them.”

It would not be until more than a half-century later that women became the subject of numerous School debates and administrative battles. This time the argument centered on whether the School should become coeducational. By 1974, the die was cast: Hotchkiss opened its doors to female students. In the early days of coeducation, girls were sometimes outnumbered ten-to-one in the classroom, and they likely were taught by a male teacher. The first female instructor was Katherine Davies, who taught Russian from 1963-64, according to the Hotchkiss Archives. There would not be another until 1967, when Annette Hunt was hired to teach music.

PHOTO: RG 101 CONNECTICUT WOMAN SUFFRAGE ASSOCIATION RECORDS. CONNECTICUT STATE LIBRARY

As World War I raged on, the boys at Hotchkiss practiced marching around the playing fields with wooden guns.

IN 1917, WHEN THE U.S. ENTERED WORLD WAR I, representatives from 35 boarding schools, including Headmaster Buehler, met in Hartford, CT, and Lawrenceville, NJ, to consider how to harness their students’ “energy and patriotic spirit” for service to the United States, according to Ernest Kolowrat ’53, writing in Hotchkiss, A Chronicle of an American School. The group focused on food production, asking each school to organize a unit of the School League for National Service by farming their own land or aiding local farmers. Buehler charged a committee of faculty with everything from gathering supplies, drafting letters to parents, and recruiting and organizing student volunteers, as well as housing and feeding them.

The School had a Battalion Squad, and boys took to marching around with wooden guns on the athletic fields, Kolowrat wrote. Those who got an acceptable academic average at the end of senior year stayed at the School and planted a victory garden that summer. Instead of requiring entrance exams, Yale accepted a certificate that confirmed that they had farmed for 60 days.

In September 1919, Buehler reflected: “Like all other headmasters of my acquaintance, the last 12 months have been the most difficult and trying period of my Head Mastership. I would not have believed in advance that a world war could so disturb academic shades. There was not a nook or cranny of our life, official or private, that the upheaval did not disturb in some way.”

When Memorial Hall was completed in 1922, the cost of the construction was donated in memory of the 22 Hotchkiss students who gave their lives in the Great War.

The Unstoppable Kevin Ervin ’04

Committed to Making a Difference for NYC Youth

BY WENDY CARLSON

IT’S EARLY AUGUST 2020, and Kevin Ervin, executive director of Change for Kids (CFK), has a month to raise $1 million for an educational outreach program he designed for New York City schoolchildren.

His enthusiasm is irrepressible, though he concedes his ambitious staff thinks he is crazy for taking on such a tough challenge under a tight deadline in the midst of pandemic. But Ervin is a bit like the Energizer Bunny, that iconic battery mascot who just “keeps going and going and going.” Once he gets an idea in his head, he is unstoppable.

Ervin grew up in a Red Hook housing project in Brooklyn, which explains, in part, why he is so passionate about leveling the playing field for public school students in the city’s underserved communities. He wants to ensure they can reach their full potential, much as he has done. In 2018, after more than a decade in youth leadership and working in educational and administrative positions in the city’s department of education, he joined Change for Kids (CFK). The 25-year-old non-profit partners with 13 city schools, providing enrichment and educational programs, resources, opportunities, mentors, and support to prepare students for middle school and beyond.

Last March, when COVID-19 struck and students were sent home for online learning, Ervin and his staff set up one of the city’s first digital educational platforms; it included a “social emotional learning” art program taught by professional artists from a variety of disciplines.

The idea behind the art program was not to single out a handful of talented kids or to “discover the next Beyoncé or Basquiat,” Ervin says. “It’s about helping kids grow socially and emotionally as they work collaboratively in group activities.”

Then, in August, when he learned that students might be splitting the week between remote learning and in-person classes, he saw a pressing need for a similar collaborative learning experience. Many schoolchildren, especially those with working parents or single parent homes, lacked a space where they could go on their remote-learning days –– a place where they would be safe, among peers, and have adult support with schoolwork.

He learned about a newly-shuttered Catholic school in the Bronx and figured he could lease it and staff it if he raised $1 million by early September. By October, he had raised $1.8 million and was finalizing leasing plans. “If we can get into this building, it would be a game-changer; we could change the proposed trajectory of students in this community,” he explains.

Much of Ervin’s can-do attitude and boundless enthusiasm were formed by his experiences at summer camp in New Jersey

and later at Hotchkiss, where he learned firsthand the power of education to create options and opportunity.

Ervin is the youngest of five siblings and the son of a working single mother; she was one of the first healthcare administrators in the country to establish HIV programs in the city. She also was a member of one of the city’s largest medical unions, which covered almost the entire cost of a summer camp that Ervin attended as a kid in New

PHOTOS COURTESY OF ATLAST MAGAZINE

Jersey.

Those summers spent with other kids from all around the world had a profound influence on Ervin’s life. “The amalgamation of camp and my Hotchkiss experiences literally created the person I am today — not only my outlook on youth development, but on the entire world,” he says.

“My first year at camp, I had a white counselor from South Africa and a Black counselor from England, which threw me for a loop as a five-year-old Black kid from Brooklyn, that there were white people from Africa and Black people from England. I experienced that level of growth every summer.”

At 15, Ervin began honing his leadership skills by working as a camp counselor. But he didn’t want to be just a counselor, he wanted to be a great counselor. As he often says, he has a big ego.

“I wanted to be the best counselor ever. So, I tried really hard. You can’t be great at youth development without really enjoying being around kids. So, in an effort to be the best, I fell in love with working with young people,” he says.

He could have easily taken a different path. As a teenager he wanted to travel the world performing, “kind of like P. Diddy,” he says. But he realized making a career in music would be financially challenging.

Instead, after a few starts and stops, he realized his true calling was in leadership, and he went on to earn a bachelor’s of science degree in leadership from Northeastern University. After graduating, he was hired to head a youth program in the South Bronx. Two years later, when the city stripped funding for the program, he plowed ahead and raised $135,000 in a month to start another youth program. Nine years later, he had students enrolled in 16 programs across New York City and New Jersey.

Ervin, who also holds an executive master of public administration degree from NYU, often tells people that the only difference between him and some of his childhood friends, who ended up in prison or worse, was that he was afforded opportunities to help himself.

Hotchkiss, for one, opened a whole new world of possibilities. Although when he first arrived on campus and saw the imposing brick buildings and columned Main Building entrance, his jaw dropped. He thought he had arrived at Hogwarts.

“I remember my mother purchased a very expensive Hotchkiss blazer because she thought every student had to wear one. I showed up on the first day of class and was the only male student wearing a blazer with the Hotchkiss Minerva on it. I went back to my room and ripped the patch off. The blazer was like $250, and at the time I didn’t have a piece of clothing that expensive. And my mom was so angry that I cut off the patch; she didn’t understand that I didn’t want to stick out from the rest of the kids.”

As a student of color at Hotchkiss he felt alienated at first. “I had been in classrooms with only people of color for most of my life, but actually it turned out not to be such a huge shock because I had gone to camp with kids of all different races and from around the world.”

“And I was extremely comfortable with who I was,” he reflects. “My proctor in Coy was Charlie Ebersol ’01. He was super cool, and he thought I was super cool, which made me feel amazing. He was making movies then, and he knew I was a musician; he enlisted me to create some music for him. And there was Raúly Ramirez ’03, a Dominican from Yonkers, NY, who kept his hair in braids and wore Jordans. He and his family sort of adopted me and brought me food whenever they came to campus. We had this interracial group of friends, and we all gravitated towards each other, which created a safety net for me and other students of color.” At Hotchkiss, he also took a stab at playing ice hockey. “I am a Black kid from the Red Hook projects in Brooklyn; we don’t play hockey. But, again partly because of my ego, I wanted to be the first Black hockey player at Hotchkiss,” he says. “Mr. Cooper gave me my first pair of skates (still got them), Burchy (Chris Burchfield) taught me how to check, and Torrey Mitchell and Pat McLaughlin taught me how to shoot,” he recalls.

Academically, Hotchkiss was a huge shift for Ervin. “New York City public schools teach you what to think. Hotchkiss taught me how to think, which is vastly different,” he says. “Hotchkiss helped me learn how to be critical, how to be intuitive and inquisitive around every subject, and to be far more analytical and strategic in my everyday life.”

Ervin plays seven instruments and has been writing music since he was seven. During his time at Hotchkiss, he jumped at the chance to study jazz, classical, and vocal arrangements and to continue his own interest in R&B, rap, and pop. Working with Fabio Witkowski, head of the visual and performing arts department, the two built the School’s first recording studio.

“Fabio played a huge role in my musicality and in my career; he was one of the first to encourage me to go against the grain, away from playing purely traditional music.

“We created the soundtrack for Hotchkiss for several years, and we got Head of School Skip Mattoon to rap for us on the ‘Fair Hotchkiss’ remix.”

Today, Ervin conducts his organization’s citywide chorus. CFK just released a cartoon for kids that he wrote, directed, and scored (featuring voiceovers from Lorenzo Castillo ’05). He also continues to work on his own music, which can be found on all major platforms and at KErvMusic.com.

Because Hotchkiss opened so many doors for Ervin, he feels compelled to pay it forward. He remembers what his Mom told him the day he arrived at Hotchkiss. “I don’t know if the grass is greener on the other side,” she said. “But, if it is, don’t stay there. Learn how to plant it, and plant it back here.”

“So now,” says Ervin, “I am planting.”

On the Beat

with Jonathan Z. Larsen ’57

BY WENDY CARLSON

In his memoir, The Perfect Assignment, Jonathan Z. Larsen ’57 chronicles the ascendancy and decline of print journalism in the 20th century.

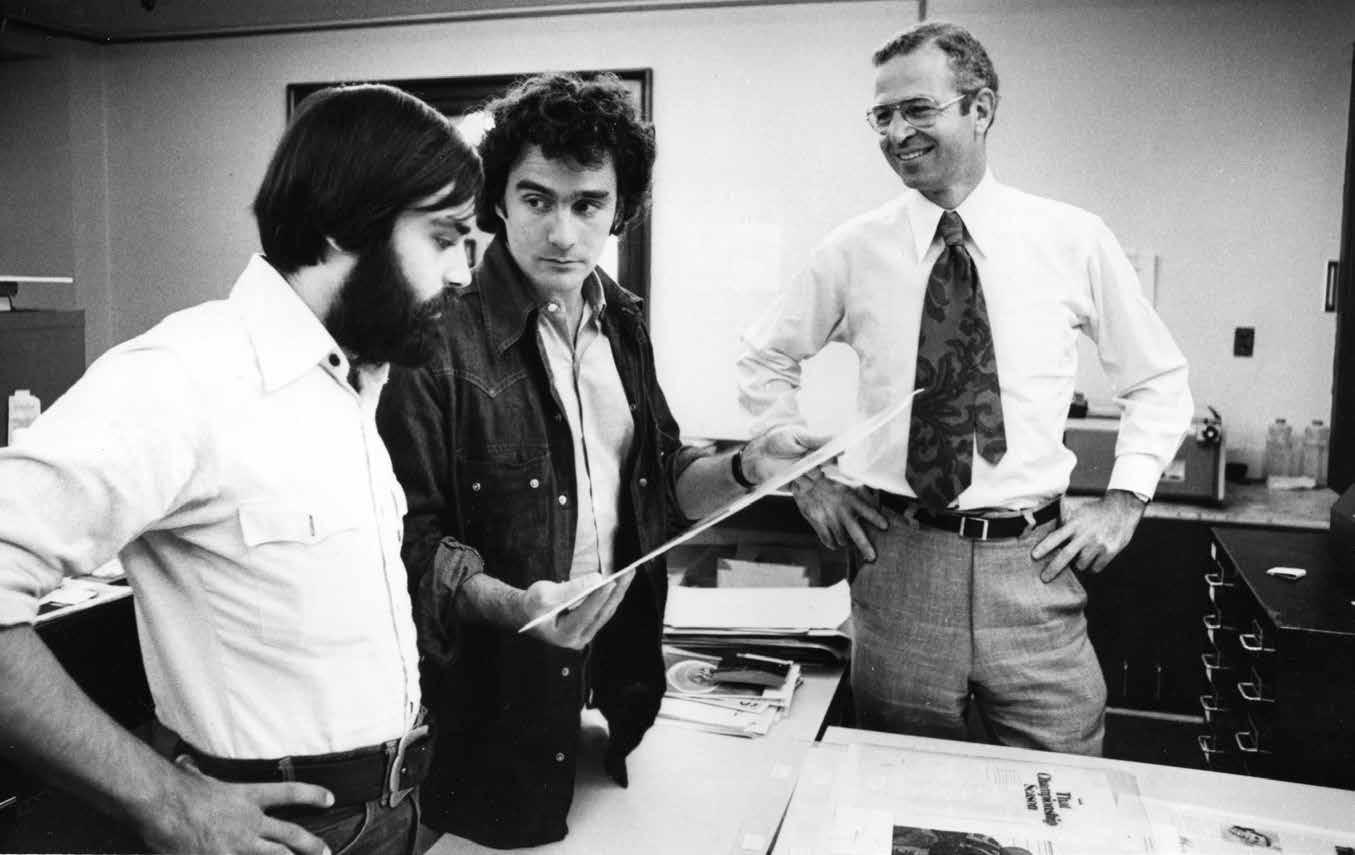

New Times art director Steve Phillips, Jonathan Larsen, and publisher George Hirsch, 1974

LARSEN BEGAN HIS CAREER at Time Inc. in 1963, where his father, Roy Larsen, spent five decades on the business side, building the news weekly co-founded by Henry Luce and Briton Hadden, both Hotchkiss Class of 1916. At TIME magazine, Larsen worked first as a writer in New York, and then as a correspondent in the Chicago, Los Angeles, and Saigon bureaus. As an editor at the magazine New Times and later The Village Voice, he focused on breaking news stories and investigative journalism. Larsen also studied as a Nieman Fellow at Harvard and was news editor at Life magazine.

Hotchkiss Magazine spoke with Larsen about major news stories he covered, those he missed, and his time with the “Coconut Monk,” John Steinbeck IV, and Jane Fonda, among others.

H: What prompted you to write a memoir about your long career in journalism?

I began writing the book for myself. I was retired, I was in recovery from two cancers, and I thought it was time to take a look back at my life. I had been brought up surrounded by bound volumes of magazines my father had published —TIME, Life, Fortune, Sports Illustrated — and now I was surrounded by 10 years of bound volumes of publications I had edited — New Times and The Village Voice — not to mention files jammed with stories I had written for TIME, New York, Manhattan, inc., and The Columbia Journalism Review. I had been an eyewitness to standout events of the second half of the 20th century — the police riot at the 1968 Chicago convention, the Manson murders, the Vietnam War — and assigned and edited stories on so many others — the JFK assassination, Patty Hearst and the SLA, the Tiananmen Square Massacre, the IRA hunger strikes, the 1989 Central Park rape, the Gulf War, the Catholic Church sex scandals... Along the way, at the very end of the century, I traveled to Oklahoma to conduct an investigation into an event that took place more than 75 years earlier but that had been lost to history — the Tulsa, Oklahoma race massacre of 1921. I believe it was the first account of that tragedy in a general-interest magazine.

H: In the book, you write about many celebrities and notable people you have interviewed. Can you share a few stories with us?

I devote some of my book to excoriating what I call “celebrity journalism,” the insidious phenomenon that made the host of the TV show The Apprentice able to run for president of the United States. My dislike of celebrity journalism began in the late ’60s, while I was the show business correspondent for TIME. I had a front-row seat as top editors turned themselves, and their magazines, inside out so that they could get near the hot new actresses of the day. So many of those Hollywood boldface names, like Raquel Welch, were not remotely worth the copy lavished on them. One Hollywood star I did come to respect was Jane Fonda. We discovered we had both grown up on remote farms with emotionally distant parents. Our mothers both attempted suicide in the same year, when we were young children. Jane Fonda’s mother succeeded. I interviewed her for a TIME cover shortly before she became famous for another career altogether, that of an ardent anti-war activist. A sign of her intelligence was the language she used to signal the changes she was going through but could not talk about to TIME magazine: “There are lives being led between all those carefully chosen, safe, staring-downthe-middle words I’m laying down for you. There’s a whole weird life going on about which I can say nothing at all — but it would make a good story.” Indeed.

In Vietnam, I became friends with Ron Ridenhour, the Army whistle-blower who wrote to Congress exposing the My Lai massacre, in which as many as 400 civilians were killed, including 120 children aged five or less. I admired his courage and moral clarity and took him on as our bureau’s stringer. He performed admirably, but the editors back in New York were not happy with my decision — they apparently considered him a traitor. Now journalism prizes are given annually in Ron’s honor.

I also spent many enjoyable hours with John Steinbeck IV, the son of the author of The Grapes of Wrath. His father was an ardent supporter of the Vietnam War, and both John IV and his brother would enlist in the Army. John would eventually testify before Congress on the rampant drug use

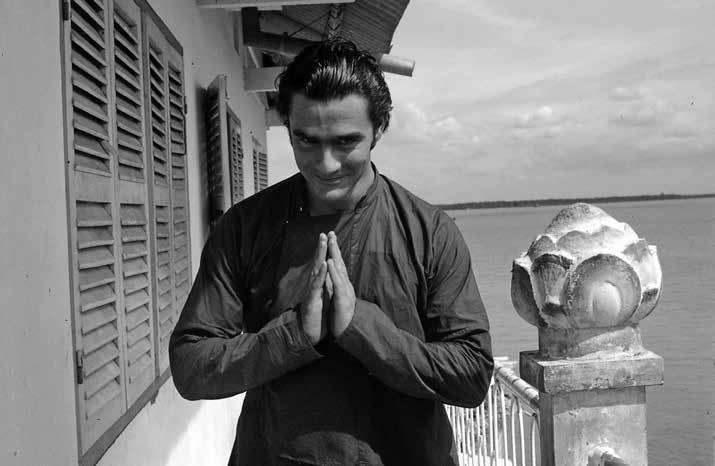

In Vietnam, Larsen became friends with John Steinbeck IV (pictured above), the son of the author of The Grapes of Wrath, who had enlisted in the army and later founded The Dispatch News Service.

Larsen (above) journeyed with Steinbeck to visit Steinbeck’s Buddhist teacher known as the “Coconut Monk.”

among the troops fighting the war. He had also been one of the founders of The Dispatch News Service, which was the first publication to break the story of the My Lai Massacre that Ridenhour had first exposed to Congress.

By the time I met him in Saigon he had become a Buddhist convert, and we made a trek together to meet his teacher, Dao Dua, also known as the “Coconut Monk,” who had taken on Steinbeck as his spiritual son. The monk presided over a theme-parked island in the middle of the Mekong Delta that featured a bridge between two towers representing North and South Vietnam. The monk’s hope was that he would bring peace to the country if enough of his followers walked back and forth across that bridge. When Steinbeck introduced me to the Dao Dua, he nodded ever so slightly. It turned out he had not spoken for three years. Steinbeck died at 44 after a botched back surgery. He had been in the midst of writing an autobiography, which was finished by his wife Nancy and published by Prometheus Books in 2001 under the title, The Other Side of Eden: Life with John Steinbeck.

H: You have a whole chapter on Donald Trump in your book. Did you ever meet him in New York?

No, I never did meet him, but like every other editor back in the day, I put him on the cover. I am happy to say that instead of the usual fawning and celebratory coverage, our 1991 cover story in The Village Voice—a long excerpt from Wayne Barrett’s book, Donald Trump: The Deals and the Downfall—was among the first unblinking looks at the man and his businesses. Barrett’s use of the word “downfall” is certainly humorous in retrospect, but at the time Trump was staggering from a series of failures and bankruptcies—the Plaza Hotel, the United States Football League, the Trump Shuttle, and of course, his failed Atlantic City casinos. There would be many more failures to come—The Trump Soho, the Trump Network, Trump University, not to mention his “charitable” organization, the Trump Foundation, which was shut down by authorities for fraud. Who could guess that anyone could survive so much failure? My favorite revelation in Barrett’s book is that Trump had lied about who his grandparents were and where they lived. They were German and lived in Queens, but for some reason those facts embarrassed Trump so he made up new ones. In his autobiography, The Art of the Deal, Trump had written—or, more accurately, had told his ghost-writer Tony Schwartz— that his grandparents were Swedish and lived in New Jersey. It would take five years, and Wayne Barrett, to correct that one simple fact. From the beginning the media has played Dr. Frankenstein to Trump’s monster. His long-time personal attorney, Michael Cohen, writes in his memoir Betrayal that Trump “screams about fake news and reporters being the enemies of the people, like a tin-pot dictator, but the truth was that the media’s psychotic fascination with Trump was one of the biggest—maybe the biggest—cause for his rise to power.”

H: Are there any particular news stories you wish you had covered?

I wish I had covered the Civil Rights marches of the mid-sixties. Even though I missed those marches of 1963 and 1964, I did cover a minor milestone of the Civil Rights movement in 1967, when I reported a cover story for TIME on the election of Carl Stokes as mayor of Cleveland. He became

the first Black person to become mayor of a major American city. While I have a chapter about this in my book, I left out the part about tearing up in the back of room as the election results were announced.

As Saigon bureau chief, I pushed back against my bosses in New York by reporting — accurately — that we were not only losing the war but losing our army along with it. They still believed what TIME had published years before, that “it was the right war, at the right time, in the right place.” They were proven wrong on every count.

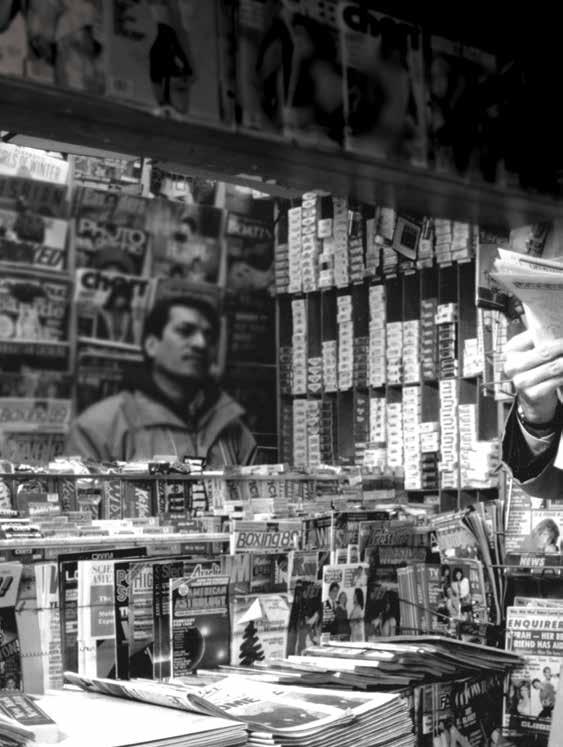

As editor of The Village Voice, I published the first investigation to detail how the New York police had blown the infamous case

Larsen, on right, with Village Voice publisher David Schneiderman outside a Hudson Newstand.

of the rape of the Central Park jogger. The so-called Central Park Five would eventually be found innocent of the crime, but at the time, the women on my own staff hated what we had published, such was the general consensus that the teenagers were guilty, and the common desire for justice. Donald Trump took out full-page ads demanding that they be put to death.

H: What is driving the hyperbolism in journalism today?

I think the nature of both television news and social media increases the insistence on eyeballs, on clicks, on likes. When you add the extreme partisanship today, you end up with the notion that everything is the best, the worst, or most horrifying ever, when in fact it is often just another day at the office. President Trump, of course, sets the tone for this. Through his tweets and his news conferences he calls everything the most wonderful or most horrible thing that has ever happened in the history of the world. It all amounts to a loss of context, or precedent ... of history itself.

H: Has the Internet made it possible for anyone to be a journalist? It has opened the door to citizen journalism, which is more democratic, but perhaps less objective. Your thoughts?

Back in the day, journalists like myself, working for the major titles that then existed, would talk to as many people as possible within the time frame allowed, weigh the facts as we understood them, and write stories that aspired to objectivity. In the best case, those stories were then fact-checked and edited to make them even more accurate, even more balanced. At least, that is the way it was meant to work. As I write in my book, the publications we worked for often had their own biases and political slants which were then superimposed on our own, either enhancing them or canceling them out. Citizen journalists bypass these difficulties and speak directly to readers, but for their part, how do readers know where these journalists are coming from? The familiar frames—TIME, The Atlantic, The Washington Post—are missing, along with their known biases. Therefore, there is a greater burden of care upon the reader.

H: What will happen to the media after the election?

Good question. The country is now divided, and so is the media, and those truths are of course connected. It is not just the personality of Donald Trump that has driven the country apart, but the new partisan business model of the media itself. The drive for ratings has crowded out more sober and responsible coverage. Whatever happens in the election, the two media camps will somehow have to close ranks and go back to reporting the facts as opposed to offering up invective, rumor, and conspiracy theories. Perhaps I should add — in your dreams.

And Justice

Justice for All

Sumi Lee ’02 Takes on a Pioneering Role for Judicial Diversity

BY WENDY CARLSON

THROUGHOUT HER TIME at Hotchkiss and in her professional career, Sumi Lee ’02 has focused on using her skills for the greater good. Community service has been both her priority and passion. So she was elated last February when she learned she was named the head of judicial diversity outreach in Colorado, a first-ofits kind position created by the Colorado General Assembly in 2019.

The effort toward judicial diversity has been underway in Colorado’s courts and the broader legal community for years, says Lee. “But up until now, it was being done mostly by attorneys and judges who were volunteering their time individually and through committee work. This program helps create a focal point for the collective effort,” she explains.

Her ultimate goal is to have courthouses and the bench reflect the community they serve. One major disparity is that there are fewer than 10 percent of Hispanic and Latino judges on the state bench, in a state that has more than 20 percent Hispanic and Latino population. Black, Asian American, Native American, and women judges are also underrepresented on the bench. “There was only one Black judge in the entire state at the end of 2018, and that created a real concern for the future of judicial diversity in Colorado and led to conversations with the state legislature that created this position,” Lee says.

More Native American judges are especially needed, particularly in the southwestern corner of Colorado — where Native Americans make up more than seven percent of the population but don’t hold any judicial offices.

Born in Korea, Lee grew up in Colorado and entered Hotchkiss as a lower mid in 1999. Former science instructor Joseph Merrill, then her chemistry teacher and the faculty advisor for Habitat for Humanity (HFH), played a role in piquing her interest in community service. For all three years at Hotchkiss, she was involved in HFH. She traveled to Georgia and Florida to build homes during spring breaks as part of a Hotchkiss contingent that participated in HFH’s Collegiate Challenge.

Those kinds of experiences would prove instrumental in steering the course of her law career, even though at Hotchkiss, she was not focused on a legal track. Instead, she deepened her love for reading and writing, which inspired her to double-major in English and Government at Georgetown.

“I was one of those people who really enjoyed writing Teagle essays,” she says wryly.

Hotchkiss also provided high-quality instruction that laid the foundation for critical thinking and analysis, which, she says, is required for a complex issue such as improving judicial diversity in a state that lacks a strong pipeline of next-generation attorneys in rural areas, known as a “law desert” issue.

At the time, her parents were a little disappointed that she did not receive any academic prizes at graduation, though she did receive a community service award, which meant a great deal to her. “In many ways,” she says, “the work I do now is an extension of the commitment to community building that I exhibited during my time at Hotchkiss.”

Lee graduated from Georgetown University and New York Law School before moving back to Colorado for her clerkship. There, she was also part of the judicial branch’s inaugural class of “Sherlocks,” or self-represented litigant coordinators, and later worked as a trust and estate attorney in the private sector.

In her new role, she is taking a datadriven approach to increase public knowledge and engagement with the judicial selection process and to create programs to encourage the next generation of attorneys and judges to consider a career on the bench, she says. Lee is working with the Center for Legal Inclusiveness, a national organization based in Denver, on its Bench Dream Team, a group of volunteer justices, judges, and others who facilitate mentorship and educational programs to encourage diversity on the bench.

“I would love to get to a point where no matter who you are or where you live in the state, you can find inspiration in the stories of the paths different judges took to the bench, where you can connect to a local network of attorneys and judges to study law and access resources when you decide to apply to the bench,” Lee says.

Eliminating barriers long before an attorney is ready to apply for a judicial position is a crucial step toward increasing diversity on the bench, according to Lee. Conversations with law students, college, and high school students should start well before students begin their legal career so that they have the resources to make their dreams of becoming a judge a reality.

As a law student, Lee was a judicial extern for a number of judges and after graduation was a law clerk. “Those experiences were critical in shaping my view of the judiciary and learning what judges do on a day-to-day basis,” Lee says.

The national focus on racial inequity has only strengthened her resolve. “I have been reflecting about my role in the context of the recent events, which have reaffirmed why the work of improving diversity on the bench is so important — that having proper representation at every level of the legal system is an important part of addressing the inequities of the justice system.”

A Flight of Alumni-owned Breweries from Aroun d t h e World

STORY BY DANIEL LIPPMAN ’08

WHAT’s

SEVERAL YEARS AGO, Matt Greenberg ’07 was driving to work at the brewery he co-founded in the Nicaraguan town of San Juan del Sur when he stumbled upon a police standoff with an armed drug trafficker, which soon developed into a shoot-out only 100 yards away.

“I did a big 180 and then took off,” he recalls. While the Pacific surf town is mostly very safe, the incident was just a reminder of the challenges that Greenberg and his business partner and friend Brendan DeBlois ’07 have faced in starting up two craft breweries in Central America.

There are those who may try to take advantage of nonlocals looking to do business. “So you’ve got to be careful, but there’s less bureaucracy,” said DeBlois.

It all started for the two of them when they went on an innocent surf trip in 2012 to the country where they were visiting fellow Bearcat Liza Daigh ’06. Greenberg was working in insurance in New York, and DeBlois was toiling away in commercial real estate in Denver, but their jobs hadn’t captured their imaginations.

DeBlois, who played lacrosse at Hotchkiss and attended the University of Denver, had worked a couple summers at Nantucket’s famous Cisco Brewery, and Greenberg, who went to Brown, was just a fan of craft beer. After getting the idea and agreeing to pursue it, the two worked on the business plan during lunch breaks of their jobs and moved down there 10 months after their first trip.

“We said to ourselves, ‘Why be America’s 5,000th craft brewery when we could be a different country’s first?’ and basically sought to open Nicaragua’s first craft brewery,” Greenberg says.

Nicaragua Craft Beer Company officially opened on Thanksgiving Day 2014 with a two-phase business model. The first was building a small brewery and brewpub, and the second involved making a deal with the country’s national brewery, so that they could brew for them and package their beer on a much larger scale for wider distribution and export.

The brewing facility for Papagayo Brewing Co. in Costa Rica, started by Matt Greenberg ’07 and Brendan DeBlois ’07

Using German malts and hops mostly from the Pacific Northwest, the brewery has four flagship beers and specializes in tropical fruit ales and dark lagers; they have also experimented with fun flavors like mango, coconut, and chocolate. While the coronavirus has slowed down sales, causing them to close down their brewpub for a few months, the company does a thriving export business and ships a container full of 2,000 cases every month between Nicaragua and New York. From there, the beer is now sold in 20 states, roughly 100 points of sale per state plus third-party delivery through online vendor Half Time and the Drizzly app. They’re also in restaurants and bars in those 20 states, and Greenberg said it’s “really satisfying” when he’s visiting a restaurant and sees his beer on the menu.

The duo’s next goal is to build a portfolio of craft beer brands in relatively immature markets throughout the world, countries where there isn’t the saturation of craft breweries that there is in North America. They plan to focus on Asia and perhaps parts of South America. Last December, they started selling their beer in a few major Chinese cities, including Beijing and Shanghai.

ON TAP

Right: Matt Greenberg ’07 enjoying a beer produced from his Central American breweries, co-owned with classmate Brendan DeBlois

In the almost six years since their company was founded, around 50 Hotchkiss alums have visited their Nicaragua brewery or the new one in Costa Rica (called Papagayo Brewing Co.) that opened last December. In 2015, Tim Krause ’10 started as the general manager of the Nicaragua brewery, and English teacher Chris Burchfield is planning on coming down next school year on his sabbatical to work with them at the brewery and immerse himself in the language and culture.

While friends often tell them that they must be living a dream by getting to drink beer and surf all the time, DeBlois, who also works as an engineer on luxury sailing yachts, said reality doesn’t always match people’s perceptions.

the company ships 2,000 cases e v e ry month between nicaragua and new yo r k . Why be America’s 5,000th craft brewery when we “ could be a different country’s first?”

“People want to be envious, but you’re trading a lot of things to be living down there; it’s not all tropical paradise,” he said. “The place is pretty rugged.”

“Whenever people say you’re so lucky for living where we live, I hate it, because it’s really not about luck,” added Greenberg. “You can make anything happen if you’re willing to make sacrifices and work hard enough to achieve your goals. But if you’re not willing to do it, you don’t actually want it that badly.”

The scene outside the Nicaragua Craft Beer Company’s brewpub.

HARRY WHALEN ’06, has also lived in a volatile city, Cairo, where some days he couldn’t even go out shopping for necessities because of the unrest during the height of the Arab Spring. It was “a very exciting time to be there, but after a few months it became pretty violent,” he said. “The city was just total chaos. You couldn’t get to work, you couldn’t get to the grocery store, the Internet was cut off. After a couple weeks of that, we thought it was unrealistic to think we could live our lives there.”

Whalen, who was an international relations major and studied Arabic at Trinity College, had moved to Amman, Jordan, for a year after college, and then tried living in Cairo for a few months, where he worked at a travel agency and tended bar on the side.

That side gig foreshadowed what he does now: after working with other Hotchkiss alums in New York City at a social media start-up, Whalen decided he wanted to start a brewery in downtown Schenectady, NY, near where he grew up.

“Hotchkiss always encouraged me to explore new opportunities, and if something piqued your interest, go for it,” he said.

After a year and a half spent finding an old Firestone tire garage, renovating the space and then buying equipment and ingredients, Whalen, who did some home brewing in college, opened Great Flats Brewing in 2017 with his brother Andrew Whalen ’03 and cousin Tom Owens, who had also been a home brewer for around 10 years.

Because alcohol is a highly regulated industry, Andrew, a fulltime lawyer, deals with the regulatory aspects of the business, while Harry runs it day-to-day, and Tom does the brewing.

Whalen admits that having a small brewery, which last year made a couple hundred barrels of beer, isn’t an easy proposition, because they’re trying to keep quality high and not take on a lot of debt as they increase production and grow the business.

“We’re a small business, and breweries are all about scale. Reaching scale in a sustainable way is sort of a balancing act,” he said. “Your margins aren’t always great.”

During the pandemic, sales have been down, and their tap room, which is their main source of revenue, was closed for almost four months before reopening in early July. But because they have very little overhead, they didn’t take a huge financial hit to their books.

To make up for the shortfall, the brewery started doing delivery and opened a takeout window in their brewery.

Before the pandemic, because of New York’s strict alcohol laws, they couldn’t deliver beer to people’s houses, and curbside ordering

Harry Whalen ’06 (middle-left) co-founded Great Flats Brewing in Schenectady, NY with his brother Andrew Whalen ’03 (right).

also wasn’t allowed. But the rules were relaxed to save New York’s thriving craft brewing industry.

Great Flats is also officially a “farm brewery,” meaning that 60 percent of its hops and barley comes from farmers in New York State. Whalen’s brewery makes a variety of beers, including American-style ales and lagers, “a pretty damn good” IPA, and also some classics, like a dark German lager and various Pilsners. They also are often experimenting by making new beers, which are valued highly by the restaurants and bars they sell to in the area.

“It’s fascinating to me that you can make a living and build a business around beer,” he said. “It’s been a no-brainer” for him to pursue a career outside of more traditional fields.

Whalen isn’t the only Hotchkiss-affiliated member of his household to start a new business in Schenectady, a city of 65,000 people. His new wife Haley Priebe ’06 is about to open up a cafe and market called Arthur’s 1795 in the historic district of Schenectady.

60 PERCENT of Great FLats’ hops a n d barley comes from new york state far m s .

CHUTINANT “NICK” BHIROMBHAKDI ’76,

P’09 is on the opposite side of the spectrum in terms of size. His company in Thailand, Boon Rawd Brewery, has three breweries and 1,400 employees, who make 370 million gallons of beer every year and are primarily known for their pale lager Singha beer.

Boon Rawd will be 87 years old this year. Nick’s grandfather founded it in 1933 and brought brewmasters over from Germany to make the beer, initially with machinery from Europe. (The original brewery is now a museum.) Bhirombhakdi, who is 60, was named CEO earlier this year, taking over the company right as COVID-19 was starting.

After going to a pre-prep school near Dartmouth, he attended Hotchkiss, where he played varsity lacrosse and JV football. Bhirombhakdi became good friends with several of his teachers, including Alban Barker, George Norton Stone, and Geoff Marchant, and is also very close with trustee Robert Chartener ’76, P’18. He says he learned from Hotchkiss the importance of being disciplined to maximize the chances of having a successful life.

After doing a joint bachelor/master’s economics degree at Boston University, he worked for a bank for a few years in New York City before heading back to Thailand to join his family

Chutinant “Nick” Bhirombhakdi ’76, P’09 is the CEO of Boon Rawd Brewery, which makes the famous Thai pale lager Singha beer.

3 70 million gallons of beer a r e p roduced by boon rawd brewery every year .

company in 1984. His first job was to learn all aspects of the business from the front end for sales to the back end, where he helped the company start to use computers for all their processes.

He’s had a variety of roles since then, from accounting to being in charge of logistics to becoming CFO in 1990. He’s also served as a senator in the Thai Parliament and helped rewrite the country’s constitution 11 years ago, after a coup. One of his daughters took after her dad with an interest in politics and is a member of Parliament; his son spent a year as a PG at Hotchkiss.

While their beer is sold primarily in Thailand, where it has a nearly 70-percent market share, it’s also exported to 40 countries, including the U.S., to which the company sends 100 containers of beer every year. Southern California and New York City are their biggest markets in America, and of the 4,000 Thai restaurants in the U.S., at least 95 percent carry Singha beer.

But they haven’t been able to crack much of the growing Chinese market yet, where he says the beer is “dirt cheap.” To adapt to changing consumer tastes over the last couple of decades, Boon Rawd has been gradually reducing the bitterness and alcohol content of the beer to make it lighter and easier to drink. They’re not compromising on quality, he says; the company still gets all their hops from Germany.

As the beer business has continued to do well for the company, the family firm has diversified into bottled water and soda and owns more than 40 hotels around the world, including 20 in the U.K. and others in Fiji, Mauritius, and the Maldives.

While Bhirombhakdi loves the beer business, he jokes that instead of taking over as CEO in the middle of a historic global pandemic: “I should be retiring, riding my Harley across the states.”

Daniel Lippman ’08 is a reporter for POLITICO covering the White House and Washington. He can be reached at daniel@politico.com.