‘BEYOND BOSTON’ CO-OPS LACK SOCIAL NETWORKS

When Northeastern students accept a co-op offer in a city out side Boston, they often have just a few months to search for living arrangements, reach out to social and professional connections and prepare themselves for a big move while they are still a college stu dent. Whether they are heading to a nearby state or a different continent, these “Beyond Boston” co-ops shift students’ lives away from Northeastern’s campus hub.

Among the factors that stu dents consider when they choose a six-month position is their proximity to the resources that they enjoy while taking classes. In 2018, The News reported that the

majority of Northeastern students preferred to co-op in Boston, but many students still choose to venture beyond the city.

Third-year business administration major Greg Guo began his second co-op search intending to remain in Boston, but an offer to join the asset management team at UBS, an investment banking company, convinced him to accept a position in Chicago for the spring 2023 cycle. Guo had previously completed a co-op at Kohlberg, Kravis, Roberts & Co. in Manhattan and said that his experience working in New York was part of why he had intended to remain in Boston for his second co-op.

By Katy Manning | News Staff

“Being in a new city makes it kind of hard to make friends, and there were only two people who actually came into work in person everyday, so it was hard to make friends with co-workers,” Guo said. “I wanted to stay with my friends in Boston and continue with the one-year lease that I signed here.”

Many workplaces have remained hybrid or fully virtual even as COVID-19 transmission has slowed. While students who remain in Boston can rely on their existing friendships, the shift has been difficult for some of those trying to make connections in an entirely new

environment. Max Huber, a thirdyear computer science major, said he has experienced this same difficulty while working at his first co-op as a research assistant for a professor at the University of Perugia in Italy.

“The first month that I was here was pretty grim,” Huber said. “I work remotely and not with other people. By coincidence, I met someone before coming here who introduced me to a bunch of people. The city where I’m in is basically a college town and there’s a bunch of American students studying abroad, so I basically pig gyback off the exchange student events that are going on here.”

At his co-op in Manhattan, Guo also made use of nearby uni versities, connecting with mutual friends at New York University and Columbia University.

“With the co-op system, you’re only going for six months, so it’s hard to form meaningful relation ships and also keep your friend ships in Boston going at the same time,” Guo said.

Though Northeastern offered a few networking events for students on coop in New York, Guo said he chose not to attend them. Huber attended one Zoom event for students going on in ternational co-ops to meet each other, which he described as “lackluster.”

Some N.U.in students to live in hotels upon return to Boston in spring

By Mia Filler News Correspondent

About 50% of current N.U.in stu dents will be housed in hotels upon their return to Boston for the spring 2023 semester, according to an Oc tober publication from Housing and Residential Life.

Due to Northeastern’s housing shortage, N.U.in students were first housed in hotels in spring 2018. At the time, just 60 students returning from the N.U.in program moved into the Midtown Hotel on Huntington Avenue. From then on, the university placed increasing numbers of N.U.in students in additional hotels such as the Westin and Sheraton, located on Huntington Avenue and Belvidere Street respectively.

SPORTS

Inside the suit of Northeastern’s mascot

Take a look behind the scenes of Northeastern’s mascot, Paws.

Due to previous rumors that students would no longer be housed in hotels, current N.U.in students are still adjusting to the possibility of liv ing in a hotel, but expressed that they are unsurprised by the recent news.

“I was on Reddit right after I got accepted into N.U.in so I knew [liv ing in a hotel] could be a possibility,” said Daniel Youssef, a first-year business administration and psychol ogy combined major currently in the N.U.in Greece program. “I wasn’t very happy about it, though.”

Over the past four years, there have been many discussions among the Northeastern com munity surrounding the effects of large amounts of first-year students living in hotels instead of on-campus dorms.

This

LIFESTYLE

Local indigenous ritual returns after three centuries Learn more about how the Nipmuc and Massachusett tribes are reclaiming their culture.

@HuntNewsNU December 2, 2022 The

News

The independent student newspaper of the Northeastern community

Huntington

PAGE 8

MULTIMEDIA 57 Questions Video Interview Series

Photo courtesy Scott Foster

Check out our video series to learn from NU club presidents.

PAGES 6-7

Photo by Marta Hill

The Westin was used as housing during the 2021-22 school year for students enrolled in N.U.in Boston.

spring, some freshmen moving in from abroad will reportedly also live in the hotel.

Photo by Colette Pollauf

Illustration by Jessica Xing

HOUSING, on Page 5

CONNECTION, on Page 5

Archives project complicates suffrage history

By Isabella Ratto News Correspondent

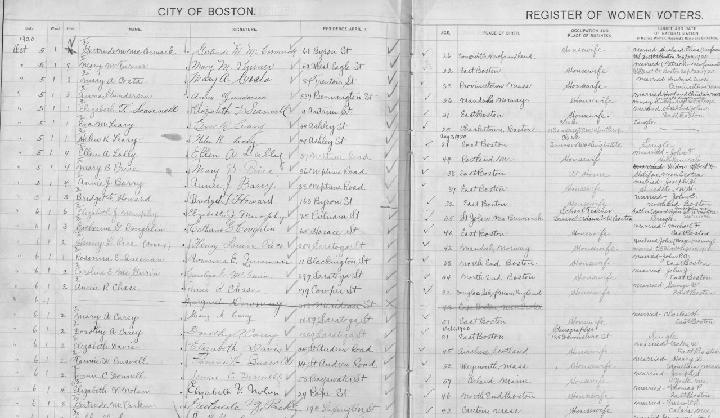

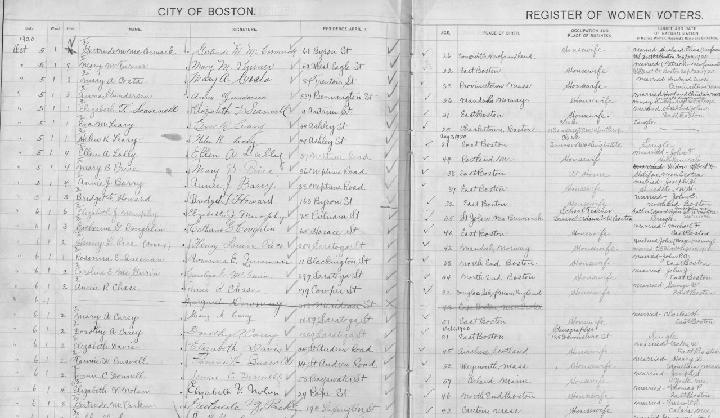

In 2021, a small team of Simmons University graduate students began work on the Mary Eliza Project, which involves the digitalization of extensive, difficult-to-work Boston voter registration records from the summer and fall of 1920.

The project, a collaborative archive transcription effort between Simmons University and the City of Boston, seeks to make the records more ac cessible while also developing a more complete narrative of the suffrage movement in Boston.

“Before this project, you’d have to come into the archives to access these records. We have 166 books [filled with hand-written registration informa tion] that are extensively organized by ward,” said Marta Crilly, an archivist for reference and outreach with the City of Boston who holds a leadership role in the transcription and research effort.

The city was divided into 26 wards during the election of 1920, Crilly said.

These records represent the first election after the ratification of the 19th Amendment, which gave women the right to vote for the first time in 1920.

The research team is looking to both make these records easier to navi gate and answer questions about the population that exercised this ability as soon as it was granted. The time-inten sive transcription work has not come without its challenges.

“It’s hard to tell, too, what the women told the clerks and what the clerks recorded. The registration en tries are filtered by the people who were writing them down,” said Erin Wiebe, a dual-degree masters stu dent in archives management and history at Simmons University who has worked on this project since its

beginning. “I think there’s a lot that gets lost in that transaction.”

This has necessitated additional research into the historical con text by the students involved. One highly fundamental area of challenge proved to be the reporting of birth place within the ledgers.

“The geography in Europe and the Caribbean are recorded differently in the register books. Clerks would record birthplace differently than we would now. The countries they’re recording sometimes no longer exist or are spelled differently,” Wiebe said.

Due to the nature of citizenship and voter laws in the early 20th century, un derstanding the geography of the time period is crucial to the transcription effort and answering questions about the population of women registering.

“In 1920, women got their citizen ship through their husbands. If your husband was nationalized, you would have access to vote. Most of the women who were denied by clerks were report ed as having ‘no papers,’” Crilly said.

In addition to presenting their own identifying paperwork at the registration booths, women were expected to have paperwork for their husbands or, in some cases, their fa thers, to substantiate their citizenship. Even after the ratification of the 19th Amendment, this fundamental right of American citizens was far from equally accessible to male and female populations, said Laura Prieto, the alumni chair in public humanities and a professor of history and women and gender studies at Simmons. Prieto is another leader of the project and oversees much of the transcription work done by graduate students.

Nationality-based concerns impact ed the demographic of this initial wave of female votes, which is of high interest to the research team at the heart of the

Mary Eliza Project. They continue to use the archives as a means of better understanding the types of women mobilized by the 19th Amendment.

“Were women of color registering to vote in 1920 in Boston?” Prieto said. “We started with the wards that were most ethnically and racially diverse at the time to try and answer that question.”

This question proved central in the earliest stages of transcription and research.

Wards 6, 8, 13, and, most recently, 1, which cover much of today’s South End, Roxbury, West End, Fenway, Beacon Hill as well as the East Boston neighborhoods, had the most racially diverse residents during the early 1920s.

Transcription of the data for women registered in these areas is complete and can be viewed in a spreadsheet format on the project’s website.

The goal of identity-based research questions, like this one focused on racial background, was to complicate the understanding of the female suf frage movement as it is largely taught and understood.

“A lot of the popular narratives of women’s suffrage in America are fo cused on the political leaders who were chiefly white women and white straight women. This project is a way to reveal the stories of black, immigrant, work ing-class women who were registering right alongside these more well-known women,” Wiebe said.

The project’s namesake, Mary Eliza Mahoney, encompasses these women who are not often talked about but contributed immensely to this political movement.

“Mary Eliza, we felt, was kind of an emblem for a lot of the research we were trying to do,” Crilly said. “She was a Bostonian. She was born in the West End. She was … one of the first African American nurses … and one of the first American Nurses Association’s Black members. She did a lot of activism … but she was also, in a lot of ways, an average person. … She was a working woman.”

Providing identity to the Boston women in this first wave of female voters, a group little is known about, continues to be of great importance

to all of the individuals working on the research team.

“We named our project after Mary Eliza because we wanted to make these questions of race and class central,” Prieto said. “We wanted to make it clear that we were considering all women, who were the grassroots, who were there to claim the right to vote.”

Work on the remaining 23 wards continues and the website is updated regularly with voter data upon the completion of each ward. Ongoing transcription of the Women’s Voter Registers is supported by a grant from the Community Preservation Act and overseen by the Boston City Archives.

Due to the nature of this grant, the publication of data for all 26 wards will be complete by the spring of 2024. Other findings and research develop ments can be found in blog posts also available on the site, including discus sions of “The Queer History of Wom en’s Suffrage” and occupation-specific groups who were mobilized to vote, including “The Women Artists of Boston’s Ward 8.”

“The blogs that we’ve written are public and written for a general audience, not historians,” Wiebe said. “There are so many different ways that people can use this data set, it’s not just for historians or genealogists. It’s for them but also people who want to know who signed up to vote on their street or in their apartment building in 1920.”

The researchers said they are excited by the multifaceted applications of the project and encourage exploration of the results they have released on the City of Boston website.

“[These archives have] something [of interest] for everyone, it felt like a sort of straightforward transformation into a public spreadsheet that anyone could use,” Prieto said.

Nonprofits fight food insecurity in Latin, Black, queer communities this holiday season

By Cathy Ching News Staff

As inflation reaches a 40-year high, expenses for basic survival needs — like food — grow increas ingly out of reach for many. Current ly, almost one in three adults, or 1.8 million, in Massachusetts struggle with food insecurity.

In efforts to provide for homeless, hungry and marginalized commu nities this upcoming holiday season, nonprofits around Boston are gath ering volunteers to package essential resources and serve the community.

“To me, food is such a basic need that people aren’t able to focus on other things in their life when they’re hungry,” said Ashley Kouyoumjian, the senior manager of development at the Greater Boston Food Bank, or GBFB. “Being able to support that is so important.”

Far and wide, households across the country wrestle with financial dilemmas: Do they use their savings to heat up their house, purchase medication or eat? For some, these dilemmas are rooted in society and the distribution of wealth.

“There are systemic barriers to financial prosperity and wellbeing and success that are prevalent in our

society and our communities,” said Xavier Andrews, the senior director of communications at United Way of Massachusetts Bay and Merrimack Valley. “Unfortunately, our Black and Latinx community members often bear the brunt of those challenges.”

As grocery expenses skyrock et, inflation allows for privileged communities to be able to access resources that are less obtainable for traditionally marginalized groups.

According to a 2021 survey conduct ed by the GBFB, the leading groups in Massachusetts adults that have faced food insecurity are in the Latinx, Black and LGBTQ+ communities, with 61%, 53% and 51%, respectively.

Among those surveyed, 86% of adults that faced food insecurity said they “perceived everyday discrimination.”

These experiences act as barriers for access to hunger-relief assistance.

With less COVID-19 precautions and the country seemingly returning back to “normal,” many have been de ceived into overlooking the everlast ing economic effects of the pandemic.

“Even though the pandemic sort of seems to be quote-unquote ‘winding down,’ in the sense that we’re not masking and social distancing as much as a general public, we’re still impacted [by] inflation and all sorts of

things that are driving people to their local food banks,” Kouyoumjian said.

The GBFB is hosting its annual two-month long Hunger Free Holi days campaign to raise awareness for food insecurity and provide meals for households. The organization uses databases to determine what foods make the most sense to serve to various cultural communities, Kouyoumjian said.

Similarly, United Way aimed to re construct the Thanksgiving stigma in its 23rd annual Thanksgiving Project — not everyone eats turkey.

“For two of our communities — South End and Quincy — we’re actu ally changing out some of the items in the grocery bags to be more culturally responsive to certain communities,” An drews said before Thanksgiving. “We’re swapping out some of the canned goods for noodles, cabbage, bok choy, just to be more responsive to the needs of the members of those communities.”

For some, however, turkey is a Thanksgiving staple. Every year on the Sunday before Thanksgiving, Boston Rescue Mission serves turkey to hun dreds of homeless and hungry commu nity members. The organization brings in dozens of volunteers — including former Mayor Marty Walsh in 2016 — to prepare and serve the food.

No matter how many days a year they contribute to giving back, nonprofit workers never overlook the efforts of volunteers.

“Without them, we probably can’t run our kitchen as efficiently,” said Mindy Zhang, a marketing specialist at Boston Rescue Mission. “It helps them [and] it helps us as well. Serv ing as a volunteer, I think they learn some important life lessons through that. They see first-hand what the homeless are experiencing.”

Volunteering is just one small step in fighting against food inse curity. During the holiday season, from November to December, vol unteerism increases by 50% because

many people view this season as a time for introspection.

Persistently combating food insecurity, however, requires community members to stand their ground year-round. Under neath the surface-level statistics of households facing food insecurity, many adults in marginalized com munities are struggling to fight against discrimination and fight for survival.

“By and large, there are structures in place that unfortunately need to be dismantled so that all of our community members can thrive regardless of race or ethnic back ground,” Andrews said.

Page 2 December 2, 2022 CITY

The City of Boston has countless voter registration documents from the 1920s. A team of Simmons graduate students have been working since 2021 to digitalize these archives.

Photo courtesy City of Boston Archives

Volunteers fill bags at the 22nd annual Thanksgiving Project at United Way of Massachusetts Bay and Merrimack Valley in 2021.

Photo courtesy United Way

Despite challenges, Boston gay men find hope

By Kevin Gallagher News Correspondent

For Aleks Hatzigeorgiou, a firstyear international business major, Boston’s accepting environment was a dramatic change from his home town of Augusta, Georgia.

There is a small LGBTQ+ com munity in Augusta, Hatzigergiou said. Pride flags are only displayed on stickers in the windows of a few downtown businesses. Growing up in the more suburban area of the city, Hatzigeorgiou said he rarely saw anything related to LGBTQ+ acceptance and pride.

“Boston is a lot different,” Hatzi georgiou said. “It’s a really diverse community of not only gay people, but lots of other people. Everyone is more accepting in many ways, especially sexuality.”

Hatzigeorgiou’s story is not unique — many LGBTQ+ people, including gay men, flock from all across the nation and the globe to come to Bos ton, often to seek higher education and a more accepting environment. According to a May 2018 study conducted by Boston Indicators and The Fenway Institute, nearly 16% of adults in Massachusetts aged 18-24 identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual or another LGBTQ+ identity.

In Suffolk County, 8.1% of adults, defined as 18 or older, identified as LGBTQ+. This is just behind Hamp shire County’s 9.0%. This makes Suffolk County second in the state in LGBTQ+ population density. The study states that “Massachusetts is also home to some of the most cut ting edge and innovative pro-LGBT social services, community resources and public policies.”

Hatzigeorgiou said he thinks the accepting attitudes of many in Boston have allowed him to be more open about his sexuality since arriv ing in the city, even allowing him to feel comfortable enough to rush and pledge a fraternity this fall.

“I didn’t go into Northeastern thinking I wanted to rush, just because of my experience with fra ternities down south,” Hatzigeorgiou said. “But fraternities here are all of the pros of a frat and none of the negatives, at least with Beta [Theta Pi]. It’s a really positive, uplifting community, and there’s a lot of diver sity in the frat.”

James Tully, a first-year bioen gineering major, echoed a similar

sentiment on coming to Boston from his small hometown of Camillus, New York, just outside of Syracuse. Before he came to Boston, Tully was only out to his immediate family and a few close friends.

“Boston is definitely a lot more liberal and open; I’m not afraid to talk to people about [my sexuali ty] here,” Tully said. “It’s not really different than what I knew at home because I wasn’t really out, so this is my first experience, but it’s been a good one, I’d say.”

However, there have been some instances throughout his time at Northeastern where Tully has been made uncomfortable by the com ments of his peers.

“Boston-wise, there’s been people here that I tend to notice being a little passive-aggressive towards me,” Tully said. “What they think is a joke is not really funny and is quite offensive. But I tend to stay away from those people.”

Tully said while he would rather avoid the people that make inappro priate jokes or comments, North eastern’s policies on harassment based on sexual orientation offer him sufficient protection and support if the harassment were ever to evolve to an unmanageable level.

Alex Cordova, a fourth-year behavior neuroscience major, said his time in Boston has also allowed his sexuality to flourish after moving here from Seattle.

“I’ve definitely become a lot more comfortable with [my sexuality], and I think that’s from finding people that I’ve been comfortable with and being able to engage with more queer people my own age,” Cordova said. “Now, I live in a bubble, essentially. Nearly all of my friends [in Boston] are queer, and it’s affirming.”

However, when Cordova goes back into straight-dominated spaces, he said he often reverts to staying alert.

“Being thrown back into those non-queer majority environments, I might feel my guard go back up again … I mean, no one has gone out of their way here to make me feel un comfortable,” Cordova said. “I think that might have to do with my exis tence as a queer person, to an extent. I’m always aware of my environment.”

Even though Cordova’s experienc es in Boston have been overwhelm ingly positive, he said Boston is lacking in one key area in compari son to many other cities of its size: a centralized LGBTQ+ neighborhood.

“Seattle, for example, has Capitol Hill, which is historically, socially and politically very queer … and almost all of the businesses are queer-owned,” Cordova said. “Here, I’ve found it a bit more difficult to find queer spaces outside of bars and clubs, specifically Club Café. A lot of the queer-centered spaces are just limited to nightlife.”

Club Café, a gay nightclub on Columbus Avenue, is one of Boston’s few LGBTQ+ gathering spaces, specifically marketed towards gay and bisexual men. The number of gay bars and nightclubs in Boston has decreased, with institutions such as The Eagle, Machine Nightclub and Ramrod all closing their doors per manently within the last few years. Boston is following the national trend of shrinking options for gay nightlife, which is a problem that has been exacerbated by COVID-19 restrictions. And, for Hatzigeorgiou and Tully, who are not yet 21, these dwindling spaces are inaccessible.

Despite all of this, Cordova, Hatzi georgiou and Tully all acknowledge that cisgender gay and bisexual men are in a place of privilege within the LGBTQ+ community.

“I definitely think that gay men have privilege over a slew of other people in the LGBTQ+ community, especially white gay men,” Tully said.

Cordova agreed, stating that toxic masculinity plays a role in white gay men’s privilege.

“I’m half Asian, and I want to say that there’s a very strong white gay majority, and that’s where I’ve seen [toxic masculinity] pervade the most,” Cordova said. “A lot of [white gay men] are still clinging on to that masculinity — that idea of ‘I’m not like other gays,’ and I’ve seen that energy directed to queer people of color.”

Even though the LGBTQ+ community still faces challenges, Cordova, Hatzigeorgiou and Tully all retain hope for their futures in Boston, as well as the LGBTQ+ community in the city.

“People [in Boston] are a lot more vocal, expressive and passion ate, which I see in both queer and straight communities,” Cordova said. “Being a student in a city of students does give me hope, at least to an extent, and the acceptance that I’ve had the privilege of meeting in my experience here gives me hope for future queer students.”

HampshireCounty

In Su olk County, home of Boston, 8.1% of adults 18 years old and older identify as LGBTQ+, second only to Hampshire County. Su olk County has a higher reported percentage of LGBTQ+ adults than both the United States at 7.0% and the state of Massachusetts as a whole at 5.0%. Massachusetts had the second highest reported LGBTQ+ population of all 50 states.

State and county data from The Fenway Institute report “Equality and Equity: Advancing the LGBT Community in Massachusetts,” May 2018. United States data from Gallup, Feb. 17, 2022

In Massachusetts, younger adults identify as LGBTQ+ more often. College-aged adults, between 18 and 24, are nearly six times more likely to identify with the LGBTQ+ community than adults 65 to 75.

Data from The Fenway Institute report “Equality and Equity: Advancing the LGBT Community in Massachusetts,” May 2018.

Graphics by Avery Bleichfeld

December 2, 2022 Page 3 CITY

Club Café, located in the South End, is a nightclub marketed towards gay and bisexual men. Students like Alex Cordova have found a refuge in LGBTQ+ gathering spaces like this.

Photo by Colette Pollauf

9.0% 8.1% 7.5%

7.0% 6.7% 6.5% 6.4% 6.1% 5.7%

SuffolkCounty FranklinCounty HampdenCounty MiddlesexCounty Essex County WorcesterCounty PlymouthCounty

UnitedStates

Massachusetts(state) NorfolkCounty Bristol County BerkshireCounty 1% 0% 2% 3% 4% 5% 6% 7% 8% 9% 10% BarnstableCounty 5.1% 5.0% 4.0% 3.7% 3.4%

Suffolk County has the second highest percentage of LGBTQ+ adults in Massachusetts

16% 12% 8% 4% 0% 15.5% 5.3% 5.7% 6.0% 10.4% 2.7% 18-24 25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65-75

SGA passes recommendations to improve emergency communication system

By Ali Caudle News Staff

Northeastern’s Student Govern ment Association, or SGA, voted on its first major resolution for the 22-23 school year Nov. 28, a Sense of the Senate on Northeastern Emergency Response and Public Safety Taskforce.

This was the work of the Student Services committee, chaired by committee Vice President Charlie Zhang, a third-year sociology and international business combined major. After the committee con ducted a survey of 73 students, 98.6% of respondents agreed that they felt NU Alert safety emails are poorly constructed and fail to convey appropriate resources.

A Sense of the Senate does not result in immediate action and is not official legislation. Rather, it serves as a public statement of the senate’s position on a specific topic and encourages the university to take up the issue.

The resolution was introduced at a full body senate meeting Nov. 14, where it was subject to questions from the senate about the accura cy of several clauses and the aim. The authors added amendments

to address the concerns prior to the debate and vote at a full body senate meeting Monday evening.

The legislation passed with a vote of 51-6 with 23 abstentions.

“We wanted to make sure that the wording of this legislation is not, ‘We are voting for these things,’ but rather that the senate is in favor of these things,” said Senator Owen Kasmin, a second-year history and political science combined major, who co-au thored the legislation. “We want these things to happen, so think of the ‘be it resolved’ clauses more like a wish list than a set of demands.”

The authors attributed their desire to take steps to create this change as a result of widespread student discontent with the NU Alert system during the hoax detonation incident in Holmes Hall Sept. 13.

Major concerns included the opt-in nature of the text alert system, a lack of timely notifica tion and vague language that made some students anxious.

“This is one of the most impor tant things that we should be doing right now as a group dedicated to the student body,” said Executive Director of Communications Olivia Oestreicher, a second-year political

science and communications studies combined major. “This is something that I think we all know that the student body cares a lot about. It was deeply concerning when this stuff was happening on campus.”

The main request of the Sense of the Senate is to facilitate the crea tion of an internal student task force in collaboration with the Northeast ern University Police Department to collectively research and develop solutions to improve safety and security at Northeastern’s campuses.

“We realized after our conversa tions with ResLife and NUPD that to future-proof this task force, it needs to have a defined set of objectives,” Zhang said. “That last clause, im proving transparency, collaboration and communication with public safety administrators captures that.”

The resolution also aims to im prove training of Resident Assis tants, or RAs, in collaboration with the task force, ResLife and NUPD. The goal is to provide more compre hensive training so RAs are better equipped to handle emergency situations and answer questions.

Kasmin motioned to adopt this legislation via unanimous consent, but it was objected to by Senator

Giovanni Falco, a second-year criminal justice and political science combined major.

“I agree with the sentiment of the legislation. I just have some concerns about the bureaucracy that it creates between NUPD, SGA, the advisory board and all the other organizations that have been encompassed into this legislation,” Falco said. “We’re adding these extra steps, an extra layer that I just don’t think is productive in getting the things we want changed done.”

Zhang addressed Falco’s con cerns about the possible creation of bureaucratic barriers. In his view, this resolution actually does a lot in the sense of helping SGA be a more vigorous advocate for community-based policing, and it opens up possibilities for en hanced communication between the community and NUPD to improve upon the current NUPD advisory board.

“The NUPD advisory board only meets, per their words, like three or four times a year,” Zhang said. “I think this very much acts as more of a funnel, so that students can work on the projects that they’re interested in, as well as having

representation on that board with public safety administrators and faculty and staff.”

The Senate then moved to con duct a roll call vote, where it passed. Kasmin said he signed on as an author of the resolution because he felt it was fairly straightforward.

“The goal of it is not to say to the university and specifically the NUPD, ‘These are things that we require and these are things that you need to work on,’” Kasmin said. “In stead, it’s ‘These are things that we want to do to make this campus saf er.’ I really think that’s an important sentiment that the senate should agree on. … We want to say that we agree to help with it, and that’s really all this legislation is doing.”

Parliamentarian Harrison Voigt, a third-year political science and eco nomics combined major, added pri or to the vote that senators should keep in mind that this legislation is just a Sense of the Senate.

“It’s meant to help in our man date and working with the admin istration on issues like this,” Voigt said. “And like a previous speaker said, this is an issue that’s really standing out on campus right now, and it needs our attention.”

Snell to remodel interior, reintroduce books to library in two-year renovation

By Catherine Tepper News Correspondent

Although Snell Library is one of the most popular study spots on campus, one thing sets it apart from many other university librar ies — its lack of books.

Dan Cohen, the dean of the library, said the last time Snell had a large collection of books was in early 2020, right before the COV ID-19 pandemic. These collections primarily took up the third and fourth floors of the library, with the fourth floor being all books and only about 200 seats, com pared to today’s 800.

During the pandemic, in an effort to reduce the spread of COV ID-19 through touching physical books, Northeastern removed and relocated all of the library’s books, using the empty space to create extra space between desks. However, Cohen said Snell Library had begun removing some of its books in 2018 after a statistical analysis done by the university found that many of the physical archives in the library were not being used by students.

Some Northeastern students who spoke with The News disagree with the university’s decision to remove the books from the library. Elias Kern, a third-year politics, philosophy and economics major, said he feels North eastern lacks a major resource by not having any books in the library.

“We could really use some books in our library,” Kern said. “I didn’t order a book that I needed for class from the Annex in time and I had to end up listening to 12 hours of an audiobook because the book arrived from the Annex the day after I was

supposed to have read it for class. … It wouldn’t have been an issue if there was a library with the book.”

This is not Kern’s only issue with the library. In addition to students not having access to these resources, the lack of books in Snell also affects the general vibe of the library, he said. The current set-up of the library is not particularly conducive to doing one’s best work, and definitely not conducive to collaboration, Kern said.

“A library is generally defined as something that has a lot of books in it. Snell is more of a workspace, com puter lab, … an academic version of an assembly line, where everyone is kind of just doing their own little thing and typing away,” Kern said.

To the benefit of students like Kern who appreciate an environ ment with access to books, the library is undergoing renovations over the next two years to make it a more comfortable study space for a diverse array of students, according to Cohen. Through these renova tions, students will see the return of high-use books into the building.

“We’re really having a once in a generation, top-to-bottom mod ernization of the library,” Cohen said. “We’re quite literally starting at the top and we’ll go all the way through the bottom. … It’s a really unique opportunity to give the entire library a really fresh and forward-looking design.”

In an Oct. 20 email statement to The News, Kerry Vautour, a member of Snell’s communication team, said the renovation will provide “compelling views, inside and out,” with a glass-enclosed central staircase and wrap-around

glass façade on the first floor. Ad ditionally, Vautour wrote that the redesign will have “more space to highlight our unique archives and special collections” and provide “on-site access to high-use books.”

Cohen said that in the five years he has been dean of the library, he has witnessed it evolve alongside the university.

“There was the launch of the Dig ital Media Commons on the second floor, the building of the recording studios, 3D printing, … recognition of the role of computers and digital media and technology in what we do to learn and do independent work and research,” Cohen said.

Northeastern is working with MGA Partners, a boutique archi tecture firm from Philadelphia, on the renovation to make each floor more coherent and themed.

“They’re doing an amazing job using all kinds of new materials that haven’t

been in the building much,” Cohen said. “There’ll be consistency in the design from top to bottom so it will really feel fully unified.”

The renovation will add seating to provide students with more study spaces, especially around the building’s perimeter and soon-to-be glass walls where there is more nat ural light, Cohen said. In addition, designers will create more collab orative and independent booka ble study rooms and the library’s basement archives will function as a study space with added desks.

For book-loving students, the university will return 40,000 archived books to the building, in addition to the 700,000 books available upon online request and 1.4 million e-books.

“We’ve done a lot of work with varying the furniture so that stu dents can find the kind of seating that they’re comfortable in, but we

wouldn’t have that opportunity un less we had the floor space,” Cohen said. “But we also know that there are good reasons to have direct ac cess to books. … So there’ll be a nice type collection that will be returned to the building.”

While the university will be provid ing students with a full array of read ing material and study spaces, one of the central goals of this renovation is to provide accommodating study spaces for a variety of students with different study styles, Cohen said.

Still, the desire for a more tradi tional library remains for some.

“Snell, and I guess a lot of North eastern, … tries to make their workspaces really fancy, but there’s something nice about being in a place where there’s a lot of books, even if it’s not visually that sleek or high-tech looking,” Kern said. “I feel like, at the very least, you should have a floor that’s dedicated to having books.”

December 2, 2022 Page 4 CAMPUS

Snell Library will undergo top-to-bottom renovations beginning in spring 2023. The library plans to reinstate highly-used and archived books in person for student use, as well as create additional study spaces.

Photo by Elizabeth Scholl

Global freshmen worry about isolation, distance in Westin, Sheraton

HOUSING, from front

“I already knew the North eastern experience was not the traditional college experience, but being housed in hotels only exacerbates that,” said first-year business administration major Dylan Hakim, who is currently in the N.U.in London program.

Some students have expressed several concerns with the idea of living in hotels. Two of the hotels NU has historically used are far ther from campus and may limit students’ ability to socialize with other Northeastern students.

Hakim also expressed concern that being in hotels would “keep the N.U.in students isolated amongst themselves,” as they will likely live with the students they spent the semester abroad with. This furthers the issue of some N.U.in students struggling to integrate with the community upon return to the Boston campus.

In addition to the news of potentially living in hotels next semester, the current N.U.in students were also informed by the university that housing priority will be assigned in order of when

students placed their enrollment deposit to Northeastern. This system is unlike most universities, many of which do a random lottery.

“I can see why they’re doing it that way, but it makes me feel bad for anyone that [submitted their deposit] later,” Youssef said. “When you’re accepted into that program it’s a hard decision to study abroad, so I can see why a lot of people wouldn’t like [this system] because it kind of feels like you’re being penalized for taking more time to make such important decisions.”

Financial status also plays a significant role in the decision making process of enrolling in the N.U.in program, first-year business administration major Zachary Chin, who is currently in the N.U.in Spain program, said.

“It says something about how Northeastern doesn’t prioritize kids who don’t have as much money,” said Chin. “Obviously if you’re early decision you’re completely fine with paying the expensive tuition at Northeastern, but then the other kids who were

not as fortunate and needed to keep their options open kind of get the last pick.”

In a statement to The News, Northeastern spokesperson Marirose Sartoretto wrote that the university never promised to stop housing people in hotels, but said housing for the spring hasn’t changed from recent years.

“It has to do with the fact that they want people to com mit earlier,” said Chin. “Maybe they hope word will spread that if you commit early you get certain privileges.”

Students working out-of-state experience isolation from sense of campus community

CONNECTION, from front

“No one really wanted to be there, and it’s not like we were going to be meeting each other anytime soon so it was kind of weird that they wanted us to share things about ourselves,” Huber said. “I feel like it makes more sense for people considering going on global co-op to hear about our experiences. Each of us was doing something radically different but all of us were in the same situation so it wasn’t that weird.”

In addition to meeting new peo ple, searching for living arrange ments on a tight timeline and a college budget provides yet another stressor for students going on co-op beyond Boston. Grace Kryzanski, a fourth-year health sciences major, said that she was almost prevent ed from accepting a position as a physical therapy aide at Two Trees Physical Therapy in Ventura, Cali fornia, due to expensive and sparse housing options in the area.

“One of the main reasons why I wasn’t going to go to Ventura was because Northeastern wasn’t doing anything for me [to find housing] and even the previous co-op wasn’t very helpful,” Kryzanski said. “The company ended up having a house that I could live in which was real ly amazing because the rent was so expensive so I’m not sure if I could have gone otherwise.”

Kryzanski completed her co-op at Two Trees during the fall 2021 cycle. Like Guo, she had begun the process seeking somewhere closer to campus.

“I applied to all other jobs in Boston and this [position in Ven tura] was kind of an on-a-whim thing,” Kryzanski said. “I was al most going to cancel my interview because I thought it was unrealis tic, but I really liked the company. I decided to go to California be cause I flipped a coin and it landed on Boston, but my gut was telling me California was right.”

In order to work around their six-month stay, expensive rates and uncertain living arrangements, both Guo and Huber used Airbnb to book housing for their co-ops. Guo said that although Northeast ern provided some housing options for co-ops in New York, he found them to be less than ideal.

“Specifically in Manhattan they have two leased properties for Northeastern students, but I didn’t end up living in either of those be cause the rent was pretty expensive and it felt like a dorm, and I didnt want to have that kind of restric tion on what friends I could bring in and at what time,” Guo said. “I found housing through Airbnb, and in New York the housing market is kind of crazy so it’s hard to find apartment leases and when you find them they’re really expensive.”

Guo plans to use the site again for his upcoming co-op in Chicago.

“At first I didn’t know that Airbnb was for more than just weekends, but you can set a date range and see what people have in the area,” he said. “You also get a longer stay discount so it ends up being comparable to other apartments in the area, and

it comes furnished. You stay in someone else’s apartment for six months, but it’s basically the same as subletting.”

Likewise, Huber said he chose Airbnb because it felt like the safest option for housing in a com pletely foreign country.

“I looked over a couple of websites and a few Facebook groups but ultimately I ended up getting an Airbnb because the websites had poor reviews and some people ended up getting scammed,” Huber said. “I wanted to be sure that my housing situation was secure.”

Huber said he spent some time looking at the housing resources that Northeastern provided, but he did not remember finding them useful. Kryzanski expressed a similar desire for help from the university.

“Being connected to affordable housing options would have been

really nice because you don’t want that to be a barrier for people and for someone to accept a co-op that is not realistic for them,” she said. “Maybe even an extension of a coop counselor to help you through that [process of finding housing] because once I got a job I wasn’t really supported.”

Huber also faced unique chal lenges going abroad. He said he “absolutely” thinks Northeastern needs to make changes to its cur rent system of supporting students.

“The process of filling out all of the forms before you actually go on glob al co-op is so terrifying and stressful and you have no idea if you’ve done the right form or talked to the right person,” Huber said. “If there’s some way to combine all of the responsi bilities that someone has to do before they go abroad, I think that would take a lot of stress off of students.

There’s multiple Northeastern organizations that all have to clear you to go abroad but none of the organizations really coordinate and none of the forms are in the same place, which makes it con fusing.”

Co-ops outside of Boston give students the chance to explore new cities without the burden of class work and expand their professional networks, a benefit of Northeastern’s extensive program. However, they can be an isolating experience and leave students without connection to either their new city or to the campus that was once their home.

“I felt like I didn’t have any connection to Northeastern at all,” Guo said. “I didn’t even check my Northeastern email and I felt like I wasn’t even a student. Other than my friends in Boston, I was com pletely separated from the school.”

December 2, 2022 Page 5 CAMPUS

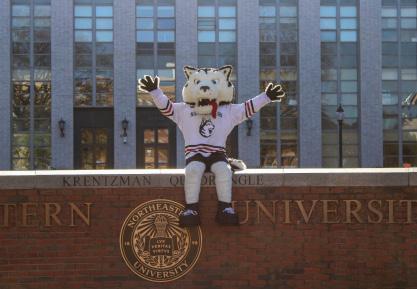

WHO IS PAWS? THE TEAM BEHIND THE ENERGETIC MASCOT

By Sarah Popeck | News Correspondent

By Sarah Popeck | News Correspondent

SPORTS Page 6 December 2, 2022

PAWS poses for photos on campus Nov. 19. The mascot interacts with students and appears at events around campus to boost school spirit.

Photos by Marta Hill

Paws isn’t just a one-man show — at Northeastern, the mascot team is composed of students who wear the suit and others who accompany them during games, acting as their right-hand man. Paws has been seen alongside the Northeastern University Police Department dog Cooper, in TikToks and at almost every sporting event.

The position is offered as a work-study job on WorkDay, showing up as a listing named “Paws.” The hiring process involves an interview to prove charisma, but the opportunity is open to all students. The team includes members of all genders and backgrounds, from expe rienced actors to novices. Even though students are sworn to secrecy during their employment and cannot reveal their iden tities, they all have fun stories and lessons to share from their experiences. The active Paws employees who spoke with The News are anonymous to protect the identity of Paws.

There are multiple Paws costumes, and the costume of the day is chosen based on the occasion and the physical size of a wearer. For games, Paws has different jerseys to correspond to the sport they are attending. Additionally, Paws travels with the various sports teams for special events; Paws gets front-row access to Beanpot, goes to Washington, D.C., for basketball tournaments and attends any NCAA events — including March Madness a few years ago.

For one current Paws castmate, this is her first experience being a mascot.

“I saw an email about the Paws team needing a skater,” the sec ond-year anonymous Paws said. “I accepted the gig because it would be silly, and it was so fun that I’ve been working on the team since then.”

In preparation for her job, she spent the entire day watching NHL mascot highlights and channeling the spirit of professionals. Her first moment at a game led to dozens more, including a special feature at Fenway Park alongside Wally, the Red Sox mascot.

“I get to do so many cool things as Paws and I’m always excited to experience new things on the team,” she said.

Lauren Murphy, a fifth-year be havioral neuroscience major, was an orientation leader in summer of 2019, and part of her job involved an opportunity to be Paws.

“A few of my orientation leader friends had been Paws before me, and it’s just such a fun experience to have and be able to say you did it,” she said.

The first time she stepped into the suit, it was a hot summer day, and the costume was filled with a big ice-pack vest to prevent over heating. She suited up for a ‘Rock, Paper, Scissors’ tournament where the mascot hung out with incom ing first-years in Snell Quad.

“It was really hard, considering Paws only has like, [four] fingers,” Murphy said.

Murphy said she walked around campus in the Paws suit, taking pic tures with people and playing games.

“It’s super fun to just see people’s

faces light up, and it’s because of you,” she said.

One requirement for Paws is the ability to skate, and some members have experience in ice hockey to supplement this. Another student

currently working as Paws shared a story about his job interview where he was asked to confirm his skating abilities — which, at the time, were nonexistent.

“I really had no idea what the job entailed going in for my inter view,” the second anonymous Paws castmate said.

The student bought a cheap pair of skates and pulled a hockey friend to the rink to master the ice.

“I’m from Florida, so I had never even put on a pair of skates,” he said.

After hours of practice, skating became more natural to him.

Currently in his fifth year of being the energetic mascot, he brings his newly-acquired skill to the ice every time he dons the Paws suit.

“My advice to anyone reading is if you ever scroll upon this job, give it a try. You can always learn how to skate later,” he said.

Now, it looks as if he has been skating his entire life, and he confidently arrives on the ice with a Northeastern flag for hockey games, welcoming fans and players.

“This job has been incredibly rewarding, so much more than I ever could have imagined when I signed up,” the fifth-year anonymous Paws said. “There are fans that I’ve seen dozens of times across all North eastern athletics events. I feel like I’ve really gotten to know

the fans and understand the impor tance and love of college sports.”

Being Paws is not just about attending athletic events. Leila Ab dul-Malak is a fourth-year psychol ogy and health science major who had her moment to shine as Paws at Convocation Day last September.

“They needed someone with a lot of school spirit who could be Paws for the day and I said, ‘heck yeah!’” she said.

Abdul-Malak learned block ing and went on stage with the Nor’Easters, an acapella music group that performed at the event. There were dozens of high fives and selfies, Paws hyped up the crowd up for the rest of college, which reminded Abdul-Malak how much her convocation meant to her.

“I love Northeastern and have a lot of husky pride, and it was a full circle moment from when I was a freshman,” she said.

Being in the Paws suit is no easy feat. Many students who spoke with The News critique the line of sight and instability they experi ence in the bulky Paws feet. “You can’t walk around in a giant dog head without occasionally taking a spill or knocking

someone down,” the second-year anonymous Paws said.

It also gets very hot in the suit, and members said they get winded due to difficulty breathing.

“I end up walking around with sweat dripping into my eyeballs,” the second-year anonymous Paws said.

The fifth-year anonymous Paws recalled one mishap that occurred when Paws got sick on the ice in front of all of the fans, throw ing up in Matthews Arena and ultimately having to step out for the night. At another game, the mascot almost took out a referee and two players when skating onto the ice.

Ultimately, every person who steps into the suit gets to put their own spin on the mascot.

Northeastern’s student section, the DogHouse, can sometimes recognize certain students because of their specific Paws interpretations. No matter the student’s experience, they have the ability to connect with students and raise the spirit.

“When I interact with students, they do most of the work for me and I play off of their energy — I learned that all that really mat ters is that you go out there and have as much fun with it as possi ble,” the second-year anonymous Paws said.

SPORTS Page 7 December 2, 2022

Paws poses with a student next to the lucky Husky statue in Ell Hall. Legend has it that students who rub the bronze snout will pass all their exams.

Photo by Marta Hill

“My advice to anyone reading is if you ever scroll upon this job, give it a try. You can always learn how to skate later.”

—

Fifth-year anonymous Paws Northeastern student

Z-Library shutdown leaves users scrambling to find alternative options

By Laura Emde News Staff

By Laura Emde News Staff

Z-Library, a database for pirated e-books, shut down Nov. 4 after the U.S. federal government seized its domains. The website’s closure left many college students in a panic, as it offered millions of e-books, including textbooks and academic journals for free.

The average cost of a college textbook is about $105, a price that

is difficult to justify for a majority of college students. In a 2014 study, 65% of college students said they didn’t purchase their required textbooks even though they knew it could hurt their grade.

Many of Z-Library’s users took to social media to express their disappointment over its demise, with some coping with humor and others blaming TikTok users for bringing more attention to the site.

Some college students in Boston expressed their disappointment after hearing about the website’s shutdown, including Quinn Roche, a second-year history and political science combined major, who pointed out how the end of Z-Library may impact students who cannot afford expensive textbooks.

“Textbooks are really expensive, so low-income students are at a dis advantage already,” Roche said. “This just only makes it harder for them.”

Some Northeastern students were concerned they would lose access to PDFs that they had downloaded prior to the shutdown.

“I thought that both of the things I downloaded wouldn’t be on my laptop, and I need them for class,” Roche said.

Although the website helped its users to save money and still finish their homework, Z-Library was in violation of multiple copyright laws.

Its alleged founders, 33-year-old Anton Napolsky and 27-year-old Valeriia Ermakova, were recently arrested and charged in Argentina. The pair may face severe conse quences and heavy fines if found guilty, according to Kara Swanson,

a professor at the Northeastern School of Law who specializes in copyright law and intellectual property, among other topics.

“[Copyright law] also provides for something called ‘statutory damages’ where you don’t have to prove what the economic loss is,” Swanson said. “There is a minimum that is the damage award per copy made. They can add up quite quickly.”

Swanson also said the events surrounding Z-Library are similar to those surrounding music piracy in the 2000s in the “pre-Spotify” world. People found guilty of sharing illegal ly downloaded music faced hundreds of thousands of dollars in fines.

“There was a case right here in Boston involving a [Boston University] graduate student that was in the federal courts for a long time,” Swanson said. “The courts kept finding him liable for extreme ly high damages and applying the statutory damages for downloading a few songs.”

Although they are high, these fines are important to authors who lose income since their work was stolen and published without their consent,

according to Swanson. A 2017 study showed that U.S. publishers lost around $315 million dollars that year due to piracy.

“You don’t have the ability to sell your work to anyone directly or to sell it to some kind of middleman … if people can get it for free,” Swanson said. “Your ability to monetize it can be diminished.”

Some former users have started to come up with alternatives to Z-Li brary, including Kendal McCloud, a sophomore film and media major at Suffolk University who used Z-Library for textbooks before the federal seizure.

“There are other websites that I’ll probably end up using,” McCloud said. “TikTok usually gives me web sites, so I’ll probably look on there.”

Although there are other easily accessible websites that offer services similar to Z-Library, the sudden shutdown still hurts for students such as McCloud, who said the website was dependable and she could find what she needed for the most part.

“Z-Lib was my bestie,” McCloud said. “They never let me down.”

Long-awaited mishoon canoe project ignites for the first time in 300 years

By Christina McCabe News Staff

By Christina McCabe News Staff

After centuries of Boston over looking the Nipmuc and Massachu sett Tribes, the tribes are now re claiming their culture and reminding the city they are not going anywhere.

Spectators gathered Oct. 31 at the Charlestown Little Mystic Boat Slip as flames danced over a 1,400 pound log. Andre StrongBearHeart Gaines Jr., cultural steward of the Nipmuc Tribe, stood tending to the log. Gaines had been there for hours already. He burned the log, scraped the ash and wet the wood — this cycle repeated until his 24-hour shift was over. It wasn’t until Nov. 6 that the burning would come to a halt, and with that came the finished product: a mishoon.

In 1685, Puritans took the land of the Massachusett Tribe and enacted a law that forbade anyone in the tribe from entering Boston unless they were escorted in by a musketeer. That law was not repealed until 2005. Elders of the Massachusett Tribe have worked tirelessly to exhibit how Indigenous tribes are still here along with countless other tribes — Chap paquiddick, Mashpee Wampanoag and Mi’kmaq — all of which volun teered in the ceremonial burning of the mishoon.

The burning of the mishoon — or canoe — is a traditional act of the Nipmuc Tribe. The act is performed by burning a wooden log continu ously until it has hollowed out into a canoe. The burn allows for the sap in the tree to waterproof the wood, which makes the canoe buoyant. For over 300 years, the Nipmuc Tribe

has been unable to perform this act due to Boston’s laws and regulations regarding burning in public spaces. But with an opportunity from the Olmsted Now Parks Equity & Spatial Justice Grants, the Nipmuc people were able to finally reclaim a sacred tradition.

“What we’re actually doing is what our ancestors did for 10,000 years,” Gaines said. “This is a footprint that has always been here that people have not seen.”

Following the ideals of Frederick Law Olmsted — an architect best known for designing the grounds of New York City’s Central Park — Olmsted Now is an organization seeking to make public parks and spaces better through shared use, health and power. This year, Olmsted would have been 200 years old. To honor his legacy, Olmsted Now created Parks Equity & Spatial Justice Grants. The grants are worth $20,000 and were awarded to 16 projects across Boston.

Gaines applied for this grant with his mission to educate and share his culture with the community and sister tribes throughout the Boston area. The Nipmuc Tribe partnered with the Massachusett Tribe to teach them the tradition of burning a mishoon. Thomas Green, Indigenous artist and educator of the Massa chusett Tribe at Ponkapoag, was the second artist who ran the project. He, like Gaines, tended to the canoe on alternating 24-hour shifts to keep the burn continuous.

“A main goal of this project was to show that we, as Indigenous people, take these sorts of things very seriously and that they can be

done in a safe space and in a safe way without any detriment or harm to the environment or surrounding communities,” Green said.

Of the 89 applications for this grant, the mishoon project stuck out immediately to Olmsted Now because of its historical significance, but also its challenging nature, according to Jen Mergel, the director of experience and cultural partnerships at the Emerald Necklace Conservancy. Boston does not allow for anything to burn in public, so achieving this project was a difficult task for Olmsted Now and the tribes. Mergel explained just how much went into allowing this cultural act.

“We really had to work hard with partners across city departments to make this possible and have a lot of really important conversations about what justice means,” Mergel said.

Although the Nipmuc and Massa chusett Tribes succeeded in bringing

back a tradition that had been stifled for centuries, their journey of cultural revitalization and awareness is just beginning.

We still have our traditional ways, our traditional languages, our cer emonies and our practices,” Gaines said. “A lot of folks don’t realize that we’re still here, you know?”

Although the open burn was able to take place for the first time in cen turies, the time frame for it is limited to five months. For Indigenous peo ple, it is difficult to achieve long-term continuity for cultural revitalization and preservation, Gaines and Green said. What they both hope to gain from this performance of a cultural tradition is recognition from Boston that they are still here.

“We, the Massachusett, are the original Indigenous inhabitants of Boston,” Green said. “For far too long, we’ve been marginalized or

overlooked or said to be nonexis tent. And it’s just important for us to make our presence known within the communities that lay inside of our ancestral homeland.”

Despite all the obstacles that came with this project, in the end, the mishoon was able to set sail in Boston Harbor.

“The canoe was lifted by Boston Public Works onto a boat trailer and brought down to the water ramp and then paddled,” Mergel said.

As for the future of the Nipmuc and Massachusett Tribes, Gaines and Green are looking to continue with their cultural revitalization efforts and perform more acts like the mi shoon project.

“This is who we are,” Gaines said. “So it’s just what we do. We’ll contin ue to build traditional homes, burn out boats, but this is who we are, so this is what we will continue to do.”

December 2, 2022 LIFESTYLE Page 8

Z-Library was a database of pirated e-books and scholarly articles in operation from 2009 to November 2022. The site was an important resource for many college students.

Photo by Karissa Korman

The burning of the mishoon — or canoe — is a traditional act of the Nipmuc tribe. The ceremony was performed for the first time in 300 years Oct. 31

Photo courtesy Scott Foster

Review: ‘Tár’ brilliantly orchestrates one woman’s downfall

By Jake Guldin News Staff

To say a lot has changed in the 16 years since a Todd Field feature graced the silver screen would be an under statement. During his absence, social media’s dominance has emerged, pro gressive movements concerned with holding bad actors accountable for their misdoings have gained consider able ground — at least online — and sociopolitical debates have erupted to an unfathomable degree.

Miraculously, writer-director Field managed to address and navigate these modern shifts — among a myriad of others — with remarkable precision, mounting intrigue and astute nuance in his latest film “Tár.”

The Focus Features release fol lows Lydia Tár (Cate Blanchett), a world-renowned conductor and com poser, as she falls out of public favor while preparing for a live recording of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony with the Berlin Philharmonic.

Blanchett was given quite the challenge for this film, as the titular character’s descent into madness is rather demanding. The Australian actress is tasked with illustrating Lydia’s complex and often contradictory feelings. With the assistance of Field’s

delicate directorial touch, though, she successfully communicates her character’s powerlessness and plight in one scene — such as when Lydia’s paranoia heightens after hearing what she believes to be a woman’s scream while jogging — before exhibiting immense confidence and control in the next — such as when Lydia directly confronts her daughter’s bully after dropping her off at school.

Beyond Blanchett’s ability to com municate her character’s wide-ranging emotions, she also perfectly captures the physicality that an accomplished composer would have. Through the waving of her baton and the gesturing of her left hand, Blanchett convincingly relays the gravitas required to corral an orchestra throughout a musical composition. This is not the only impressive physical element of her performance, however, as Blanchett’s ability to switch between languages and accents — Lydia is shown to be fluent in English, German and French — comes across as absolutely effortless.

Other standouts include Nina Hoss, Noémie Merlant and Zethphan SmithGneist, who play Sharon Goodnow (Lydia’s wife), Francesca Lentini (Lydia’s assistant) and Max (a Juilliard student who clashes with Lydia during a class), respectively. Any of these

performers could have been easily overshadowed by the ever-imposing Blanchett but, luckily, they measure up. As a result, the trio assists greatly in establishing the palpable tension felt throughout the film’s lofty two-hourand-38-minute runtime.

But, as Lydia declares while guest teaching at Juilliard: “If you want to dance the mask, you must service the composer.” Fortunately, the performers have one hell of a composer to subli mate themselves to in the Oscar-nomi nated auteur: Field.

Through “Tár,” the auteur behind “In the Bedroom” and “Little Children” crafts a thematically rich and thorough ly engrossing commentary on the mod ern social convention of cancel culture. Field, unlike other artists, refuses to por tray this issue in absolutes; he refrains from assessing whether this newfound norm is beneficial or detrimental to discourse. Such abstention allows viewers to grapple with Lydia’s actions — ranging from “unwoke” opinions to credible accusations of her grooming past students — on their own terms, which, in a media landscape where works frequently spoon-feed audiences political messaging, is refreshing. Aside from trusting his audience to form their own opinions on what they are seeing, Field has enough faith

in them to make a number of bold choices in both his screenplay and direction — choices largely hinging on the viewer’s ability to follow the film maker along a deliberately paced and understated narrative. The film’s open ing scene, for instance, is essentially 10 minutes of exposition exploring Lydia’s early life, adulthood, achievements and current endeavors. The scene is, for the most part, a single unbroken shot. Such a description may make this film’s beginning moments seem dull and tedious — and they should be. Yet, they are not. Field’s masterful writing, assured direction and unwavering belief in his audience come together to defy the odds and transform what should have been a banal introduction into something both daring and rivet ing in equal measure.

Further enhancing Field’s symphon ic masterwork is a subtle yet cleverly utilized score by Hildur Guðnadóttir, tone-setting cinematography courtesy of Florian Hoffmeister and skillful, unobtrusive editing by Monika Willi.

From its innocuous first frame to its shocking last, “Tár” is a showcase of the awe-inspiring talent of the individuals behind it and, much like the music of Mahler or Elgar, it is sure to be remembered and celebrated for centuries to come.

Erin Rosenfeld advocates for Deaf inclusion in theatre

By Christina McCabe News Staff

When it comes to advocating for the Deaf community, Erin Rosenfeld, a fourth-year American Sign Language and psychology combined major, has gone above and beyond to make sure people who are hard of hearing have a place, especially in the theatre.

“I want everyone to know and feel that they have a place where they fit and where they can just easily exist and not have to fight for accessibility, accommodations and respect,” Rosenfeld said.

Rosenfeld has devoted most of her teenage and young adult life to advocating for disabled people, and she has gained substantial recognition for her efforts. She first started gaining recognition as an advocate through her platform on TikTok. What started out as a hobby during the lockdown period of the COVID-19 pandemic soon turned into her amassing a following of more than 300,000 people. Her videos first blew up after she brought attention to how the presidential debate broadcasts did not have a closed captioning option. After that, she landed a spot in Teen Vogue magazine and Forbes for her efforts to bring awareness to an issue that was overlooked for too long.

Politics aside, Rosenfeld has also made efforts to make theatre more accessible for disabled people. She has always had an interest in musical theatre, but she often found it hard to feel included in a production due to her deafness.

“It was very difficult because it’s hard to sing when you can’t necessarily

hear the notes or hear music in a way that hearing people do,” Rosenfeld said. “So that was always really hard. I was always really self-conscious. I had these moments where I was like, ‘I don’t want to do theater. I don’t want to act anymore.’”

Despite all of the challenges she faced, Rosenfeld persevered with her passion and decided to change the way she approached the theatre.

“I began signing instead of singing and it fits, if that makes sense,” Rosen feld said. “It feels so much better and more authentic than when I thought I had to sing, and I can truly connect to the characters and express myself in sign language.”

Last spring, she decided to take her talent to the stage at Northeastern and audition for “This Is Treatment,” a play written and co-directed by Elizabeth Addison, a playwrite, which centers around a girl struggling to recover from substance addiction.

Rosenfeld auditioned for this play, but instead of singing, she submitted a video of her signing to a song.

“She sent a video of her interpreting a song,” Addison said. “She interpret ed it through ASL and said that she doesn’t sing, but this is what she does.

And if I would be open to having her audition for the musical in doing this interpreting song through ASL, I’d let her know. So I watched it and imme diately I was like, ‘Oh my goodness, she’s cast.’”

Addison was blown away by Ros enfeld’s performance as an interpreter, which she said she feels it “added another layer” to the play.

“It was just so beautiful,” Addison said. “And people would get captured

by just watching her. So you have all this sort of stuff happening and people would be watching her because of the way she does it and there’s just some thing so profound about it. And so just what she does made the show even better to me.”

After her performance, Rosenfeld decided to apply for the The Danny Awards, an award that acknowledges disabled individuals around the world for their talent in the musical industry — she was chosen as one of 11 recipients.

Like many Northeastern students, Rosenfeld has taken her passion to her work — she is on co-op for Access Broadway. The company strives to make Broadway theatres more accessible for those with disabilities. In her role, Rosenfeld is responsible for checking accessibility devices and closed captioning devices.

Access Broadway also works towards making sure theatres follow the Ameri cans with Disabilities Act guidelines.

“Sometimes in order to meet the requirement for how many accessible seats are needed in a theatre, some theatres will designate a couple of feet in the balcony or the mezzanine as wheelchair accessible, even though there’s no elevator to get up there,” Rosenfeld said. “So they’re not truly accessible, but they can say on paper that they are.”

Rosenfeld’s advocacy is impactful in more ways than one. Kelty Kober, a second-year majoring in American Sign Language, said she admires all that Rosenfeld has accomplished for the Deaf community.

“She’s like a role model to me,” Kober said. “I am deaf and I have

cochlear implants, and Erin is someone who knows sign language and has hearing aids, and she’s hard of hearing. She’s just doing awesome and like, I really want to be her. I know that’s not possible, but I really look up to her and she’s a great role model to anybody and a great friend.”

Now that her co-op is coming to an end within the next month, Rosenfeld said she is hopeful she will continue with this career after she graduates next May and continue to bring awareness to the Deaf and disabled community.

“I would love to continue advocating and continue spreading awareness,” Rosenfeld said. “I don’t think awareness and accessibility are difficult things; I think they’re definitely attainable. And so I just want to keep fighting until we get there.”

Friday, Dec. 2

Light Up Seaport

Head out to the Seaport for the annual tree lighting and some yuletide cheer.

5 p.m. - 9 p.m., 85 Northern Ave., Boston, Free.

Dec. 3 - Dec. 4

“Seussical”

See a variety of Dr. Seuss charac ters — The Cat in the Hat, Horton the Elephant and more — interact in NU Stage’s rendition of the musical, “Seussical.”

8 p.m. - 10 p.m., 342 Huntington Ave., Boston, Free.

Sunday, Dec. 4

Newton Holiday Craft Fair

Celebrate the holidays with local art and live music.

10 a.m. - 4 p.m., 140 Brandeis Rd., Newton, $5 to enter.

Tuesday, Dec. 6

Midwxst with Frost Children

Revel in some truly unique hyperpop, courtesy of GLR, CUP and LMA, during this holiday celebration.

6:30 p.m. - 9:30 p.m., 360 Huntington Ave., Boston, Free.

Dec. 9 - Dec. 18

Harvard Square Holiday Fair

Shop holiday gifts from vendors selling photography, jewelry and all things vintage.

11:30 a.m. - 7 p.m., 33 Dunster St., Cambridge, Free.

Page 9 LIFESTYLE December 2, 2022

Calendar compiled by Cathy Ching & Jake Guldin Graphics by Emma Liu

Rosenfeld gives her acceptance speech at The Danny Awards, an award that acknowledges disabled individuals around the world for their talent in the musical industry. She was chosen as one of 11 recipients.

Photo courtesy Daniel’s Music Foundation

NEWS STAFF

COPY EDITORS

Op-ed: Elon Musk brings down Twitter

Because of Musk’s purchase of Twitter, it has become an even more hostile place for minorities. It’s truly impressive how one’s management of a site further boosted the level of hate speech on a platform already known for harboring some of the most hateful commentary posted online, but Musk did not disappoint.

ing Twitter to take action. Musk decided to ban any account that did this if they didn’t clearly state in their display name or bio they were a parody account.

DESIGN STAFF

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Well, it’s official: Elon Musk now owns Twitter, one of the most popular social media platforms. A paragon of “free speech,” one of Musk’s ultimate goals following his acquisition of Twitter was to, according to the Financial Review, “help humanity” because “free speech is the bedrock of a functioning democracy and Twitter is the digital town square where matters vital to the future of humanity are debated.” Essen tially, he wanted to purchase Twitter in order to reinstate “free speech.”

However, what that really means is that individuals can now spew anything including things generally considered bigoted. In fact, not long after Twitter was purchased by Musk, usage of the N-word alone rose by 500%, almost certainly coming mostly from accounts owned by white people who think they are comedic geniuses, as well as other racists. That’s strike number one, Musk.

There’s another major change Musk made to the platform: paid verification. For a brief time, users could purchase the esteemed blue verification check mark that many a celebrity, influencer, politi cian and more bear. Though the program is temporarily suspended, Elon Musk announced he has plans to relaunch a new version of the paid verification system. So now, verification on Twitter is practically meaningless. In all honesty, we should have seen this coming. It’s almost a joke at this point that billion aires such as Musk are looking to milk everyone’s money, but Musk’s attempt to generate profit via the new verification system is not a joke at all. Moreover, the price for that beautiful blue checkmark on one’s profile was initially going to be $20 a month, though Musk lowered it. That’s strike number two, Musk.

In response to this, many users, such as Ethan Klein of H3H3 Productions, bought verification and changed their display names to those that resemble celebrities and other verified users, giving the impression that the user who definitely wasn’t a favorite celebrity was a favorite celebrity. These same users would tweet some rather hilarious things under these false aliases, prompt

Nevertheless, some accounts that fol lowed this guideline were still banned. Additionally, tweets criticizing Musk and his recent changes to Twitter would frequently disappear from the platform for ”violating community guidelines.”

That doesn’t sound like the imple mentation of “free speech” Musk was striving to achieve when he acquired the platform, does it? So is his acquisition of the site really about free speech, or is it about wanting to go on a power trip and earn even more money than he already has? That’s your third strike, Musk.

Oh, but he’s not finished yet. Musk has responded to much of the criticism he has received but his responses were weak at best and childish at worst.

In response to backlash against paid verification, he posted a “wojak” meme criticizing critics of paid verification by claiming that we pay the same amount for one month’s worth of verification ev ery day when we pay for our Starbucks drinks, which only last us 30 minutes, according to the meme. This is imma ture logic, and the argument immedi ately crumbles once you acknowledge the obvious: Twitter verification is not the same as a Starbucks order.

Aside from that, Musk has made a smart choice with regards to rectifying his new verification system. He has decided to add a feature that allows you to check whether or not someone is verified due to their notoriety as a figure