26 minute read

PREMIER ISSUE

EXPLORING IMPRESSIONISM FROM THE 19TH CENTURY TO PRESENT DAY The Impressionist SUMMER/FALL 2020

Complimentary

Advertisement

ISBN 978-1-7345977-1-4

9 0 0 0 0 >

ERIN HANSON: Colors of California

ERIN HANSON: Colors of California

The Santa Paula Art Museum presents a solo exhibition by Erin Hanson. Erin Hanson: Colors of California will mark Hanson’s most comprehensive collection of California’s multitudinous landscapes. Inspired by the changing seasons and colors of California’s vineyards, coastlines, hills and oak trees, Erin Hanson has spent fifteen years exploring California’s rural landscapes and capturing their natural beauty on canvas.

Erin Hanson: Colors of California will include over forty original oil paintings ranging in size from petite to grand-scale works. The collection will include landscapes inspired by Ventura County, Santa Barbara, Paso Robles, Monterey County, Mendocino and other scenic locales.

EXHIBITION DATES: MARCH 13TH - JULY 11TH, 2021

EXHIBITION DATES: MARCH 13–JULY 11, 2021

WAVES OF GOLD 20 x 24 IN

ABOUT THE SANTA PAULA MUSEUM

The Santa Paula Art Museum belongs to you. The Museum’s collections, exhibitions, and programs are designed to serve and inspire everyone in our community. The Santa Paula Art Museum features rotating exhibitions of regional art, educational programming for children and adults, artist talks and demonstrations, musical performances, a gift shop, and more. The Museum’s permanent collection includes over 200 historical and contemporary works of art. The Santa Paula Art Museum is also in part the repository and exhibition hall for the Santa Paula civic art collection. This extraordinary assemblage is composed of nearly 300 award-winning entries from the annual Santa Paula Art Show begun in 1937.

The Museum is housed within the historic Limoneira Building. Built in 1924, the classic two-story structure was designed by the famed local architect Roy Wilson, Sr. to accommodate the offices of the Limoneira Company. The architectural details of the exterior of the building hint at the interior’s handsome wood paneling, soaring windows, and stunning atrium. Through a lease agreement with the Limoneira Company, their former headquarters was renovated and reopened as the Santa Paula Art Museum in 2010.

Dear Readers,

Welcome to the premier issue of The Impressionist. The purpose of this magazine is to educate art lovers about impressionism and excite fresh appreciation for this style of painting.

The Impressionist showcases articles about the advent of impressionism in Europe, as well as the development of post-impressionism and contemporary impressionism. The authors searched for fascinating and little-known facts about the impressionists, and I hope you find the articles interesting.

I am indebted to My Modern Met and The Art Story for letting me reproduce their articles herein. Many of the images used in this magazine are reproduced courtesy of Creative Commons or are public domain images. Credits are given to galleries and non-profit organizations who lent me use of their images. I hope you enjoy the artwork.

Thanks for reading!

Amy Jensen Editor

The Impressionist

VOLUME 1, NUMBER 1 • SUMMER/FALL 2020

ON THE COVER Crystal Impressions, Erin Hanson (2020) Oil on canvas, 36 x 24 in.

This is a free publication with the purpose to educate art lovers about impressionism and excite fresh interest for this style of painting. POSTMASTER: You can receive your free copy of this magazine by sending your address to Red Rock Fine Art, 9705 Carroll Centre Road, Suite 102, San Diego, California 92126. Measurements are in inches, height x width. Image credits are given on-page. See more information on page 80.

To receive your complimentary digital copy of The Impressionist, please email contact@redrockfineart.com

The Impressionist (ISBN 978-1-7345977-1-4) is published by Red Rock Fine Art, Inc., 9705 Carroll Centre Road, Suite 102, San Diego, California 92126.

Email: contact@redrockfineart.com

All content copyright © 2020 by Red Rock Fine Art, Inc. (except where otherwise noted). All published content may not be reproduced in any form without written permission from Red Rock Fine Art, Inc.

Editor Amy Jensen Publisher Erin H nson Design and Production fourcolorpl net.com Contributing Writers C ristine Bond, P ul D. S oden, Jo n Frenc , Norm n Kolp s Printer H rtley Press, Inc.

Contents

20 The Birth of Impressionism from Realism y Kelly Ric m n-A dou wit permission of My Modern Met

26 Four Friends—The Foundation of Impressionism y C ristine Bond

36 The Man Behind the Impressionists y P ul S oden

40

Van Gogh—Beyond Impressionism reproduced wit permission from t e rtstory.org

50 Van Gogh’s Most Famous Paintings

54 Birger Sandzén—Van Gogh of the West y Jo n Frenc

58 Mavericks Turned Masters y Norm n Kolp s

80 Resources

The Birth of Impressionism from Realism

Admired by art experts, popular with the public, and widely exhibited in the world’s top museums, Impressionism has dominated the art world for nearly 150 years. Renowned for its painters’ pioneering approach to art, the groundbreaking genre has facilitated the emergence and shaped the evolution of several art movements, solidifying its role as the catalyst of modern art.

While Impressionism’s distinctive aesthetic is undoubtedly one-of-akind, the context of the canvases is just as captivating. Here, we explore the

By Kelly Richman-Abdou

with permission of My Modern Met.

background, characteristics, and legacy of Impressionism to illustrate the iconic movement’s profound impact on the history of art.

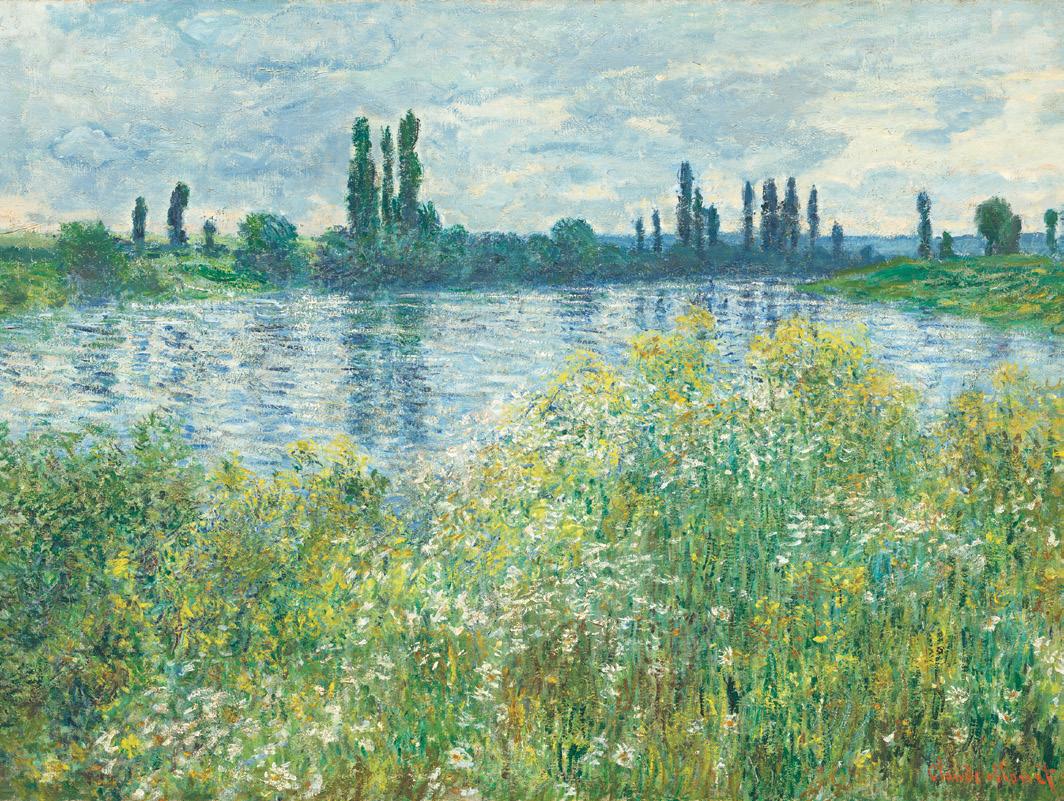

Impressionism is a movement of art that emerged in 1870’s France. Rejecting the rigid rules of the beaux-arts (“fine arts”), Impressionist artists showcased a new way to observe and depict the world in their work, foregoing realistic portrayals for fleeting impressions of their surroundings—which, often, were found in the broad outdoors.

“Instead of painting in a studio, the impressionists found that they could capture the momentary and transient effects of sunlight by working quickly, in front of their subjects, in the open air

BANKS OF THE SEINE, VÉTHEUIL Claude Monet (1880). Oil on canvas, Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington. Chester Dale Collection.

(opposite) WOMAN WITH A PARASOL— MADAME MONET AND HER SON Claude Monet (1875). Oil on canvas, Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington. Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon.

(en plein air) rather than in a studio,” the Tate explains. “This resulted in a greater awareness of light and color and the shifting pattern of the natural scene. Brushwork became rapid and broken into separate dabs in order to render the fleeting quality of light.”

This new approach to painting diverged from traditional techniques, finally culminating in a movement that changed the course of art history.

(above) NEAR THE LAKE Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1879–1890). Original from The Art Institute of Chicago. CC0 1.0. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.

(opposite, top) BOIS DE LA CHAISE (PAYSAGE) Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1892). CC0 1.0. Original from Barnes Foundation. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.

(opposite, bottom) MEADOW (LA PRAIRIE) Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1880). Original from Barnes Foundation. CC0 1.0. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.

Throughout the 19th century, most French painters produced work that adhered to the traditional tastes of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, a Paris-based organization that held annual salons. Showcasing a selection of hand-picked artwork, the salons tended to favor conventional subject matter—including historical, mythological, and allegorical scenes—rendered in a realistic style.

Tired by this age-old approach to creativity, a group of artists decided to skip the salon hype and, instead, host their own independent exhibitions. Known as Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs (“Cooperative and Anony

mous Association of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers”), this band of artists—which included Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro—held their first exhibition in 1874.

Set in the studio of Nadar, a French photographer, the exhibition featured several paintings by 30 artists, with the most notable being Claude Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (1872).

The exhibition saw mixed reviewed from critics, including journalist Louis Leroy. When analyzing Impression, Sunrise, he infamously wrote: “Impression—I was certain of it. I was just telling myself that, since I was impressed, there had to be some impres

ROCKS AT PORT-GOULPHAR, BELLE-ÎLE

Claude Monet (1886). Original from the Art Institute of Chicago. CC0 1.0. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.

(opposite) THE CAFE CONCERT (THE SONG OF THE DOG) Edgar Degas (1875- 1877). Gouache, pastel. Courtesy of WikiArt.

sion in it … and what freedom, what ease of workmanship! Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape.”

Though clearly intended as an insult, his review actually helped the movement—it inadvertently (and ironically) gave it its well-known name. q

Van Gogh Beyond Impressionism

Vincent van Gogh was born the second of six children into a religious Dutch Reformed Church family in the south of the Netherlands. His father, Theodorus van Gogh, was a clergyman and his mother, Anna Cornelia Carbentus, was the daughter of a bookseller. Van Gogh reportedly exhibited unstable moods during his childhood, and showed no early inclination toward art-making, though he excelled at languages while attending two boarding schools. In 1868, he abandoned his studies and never successfully returned to formal schooling.

Article reproduced with permission from theartstory.org

In 1869, van Gogh apprenticed at the headquarters of the international art dealers Goupil & Cie in Paris and eventually worked at the Hague branch of the firm. He was relatively successful as an art dealer and stayed with the firm for almost a decade. In 1872, van Gogh began exchanging letters with his younger brother Theo. This correspondence continued through the end of Vincent’s life. The following year, Theo himself became an art dealer, and Vincent was transferred to the London office of Goupil & Cie. Around this time, Vincent became depressed and turned to God.

After several transfers between London and Paris, van Gogh was let go from his position at Goupil’s and

WHEAT FIELD WITH CYPRESSES Vincent van Gogh (1889). Original from the MET Museum. CC0 1.0. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.

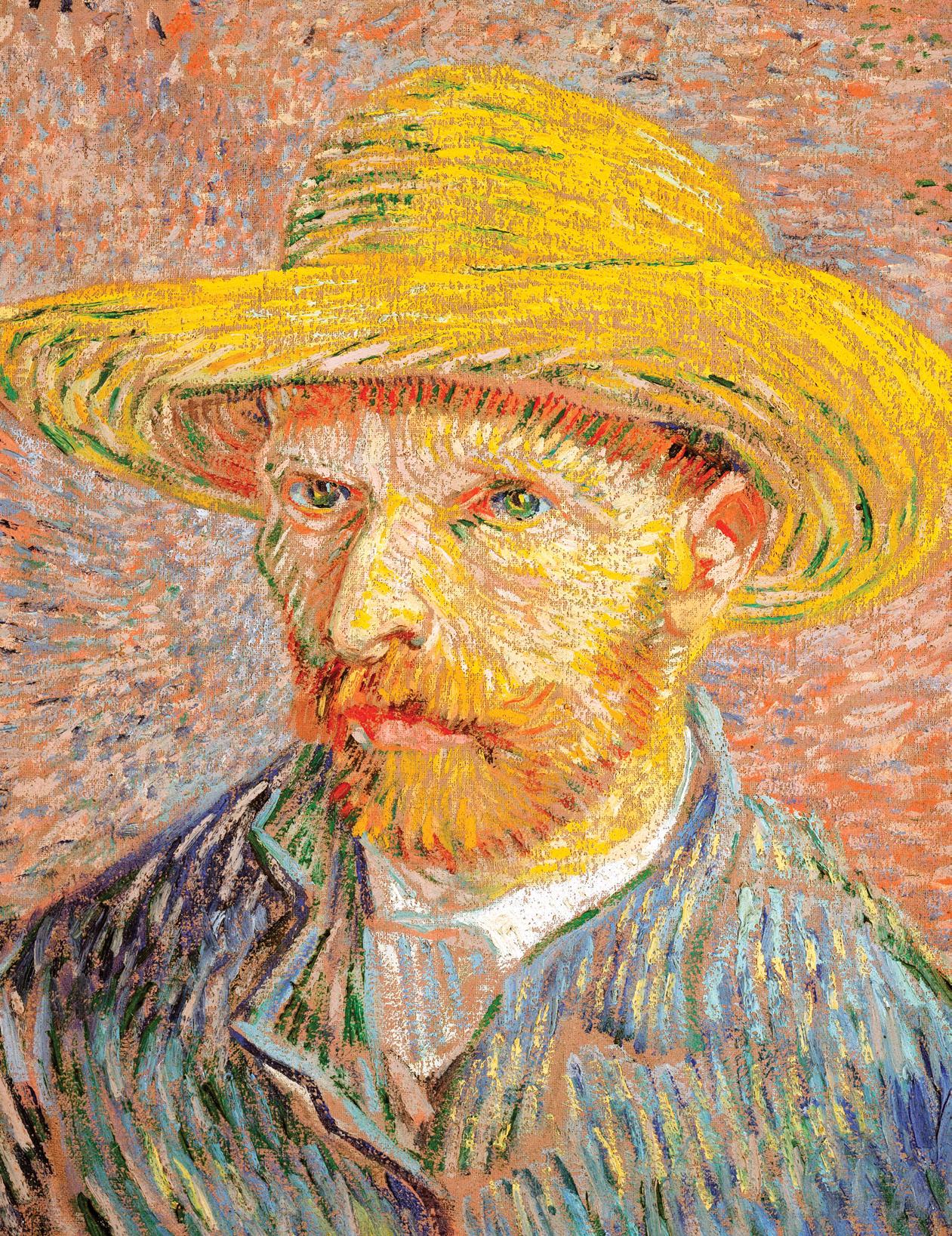

(opposite) SELF-PORTRAIT WITH A STRAW HAT Vincent van Gogh (1887). Original from the MET Museum. CC0 1.0. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.

decided to pursue a life in the clergy. While living in southern Belgium as a poor preacher, he gave away his possessions to the local coal-miners until the church dismissed him because of his overly enthusiastic commitment to his faith. In 1880, van Gogh decided he could be an artist and still remain in God’s service, writing, “To try to understand the real significance of what the great artists, the serious masters, tell us in their masterpieces, that leads

(above) OLIVE TREES Vincent van Gogh (1889). Original from the MET Museum. CC0 1.0. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.

(left) SUNFLOWERS Vincent van Gogh (1887). Original from the MET Museum. CC0 1.0. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.

(opposite) IRISES Vincent van Gogh (1889). Original from the J. Paul Getty Museum. CC0 1.0. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.

to God; one man wrote or told it in a book; another, in a picture.” Van Gogh was still a pauper, but Theo sent him some money for survival. Theo financially supported his elder brother his entire career, as Vincent made virtually no money from his paintings.

A year later, in 1881, dire poverty motivated van Gogh to move back home with his parents, where he taught himself to draw. He became infatuated with his cousin, Kee Vos-Stricker. His continued pursuit of her affection, despite utter rejection, eventually split the family. With the support of Theo, van Gogh moved to

the Hague, rented a studio, and studied under Anton Mauve — a leading member of the Hague School. Mauve introduced van Gogh to the work of the French painter Jean-François Millet, who was renowned for depicting common laborers and peasants.

In 1884, after moving to Nuenen, Netherlands, van Gogh began drawing the weathered hands, heads, and other anatomical features of workers and the poor, determined to become a painter of peasant life like Millet. Although he found a professional calling, his personal life was in shambles. Van Gogh accused Theo of not trying hard enough to sell his paintings, to which Theo replied that Vincent’s dark palette was out of vogue compared to the bold and bright style of the Impressionist artists that was popular. Suddenly, on March 26, 1885, their father died from a stroke, putting pressure on van Gogh to have a successful career. Shortly afterward, he completed the Potato Eaters (1885), his first large-scale composition and great work.

Leaving the Netherlands for the last time in 1885, van Gogh enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp. There he discovered the art of Baroque painter Peter Paul Rubens,

whose swirling forms and loose brushwork had a clear impact on the young artist’s style. However, the rigidity of academicism of the school did not appeal to van Gogh and he left for Paris the following year. He moved in with Theo in Montmartre - the artist’s district in northern Paris - and studied with painter Fernand Cormon, who introduced the young artist to the Impressionists. The influence of artists such as Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Edgar Degas, and Georges Seurat, as well as pressure from Theo to sell paintings, motivated van Gogh to adopt a lighter palette.

From 1886 to 1888, van Gogh became acutely interested in Japanese prints and began to avidly study and collect them, even curating an exhibition of them at a Parisian restaurant. In late 1887, van Gogh organized an exhibition that included his work and that of his colleagues Emile Bernard and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and in early 1888, he exhibited with the Neo-impressionists Georges Seurat and Paul Signac at the Salle de Repetition of the Theatre Libre d’Antoine.

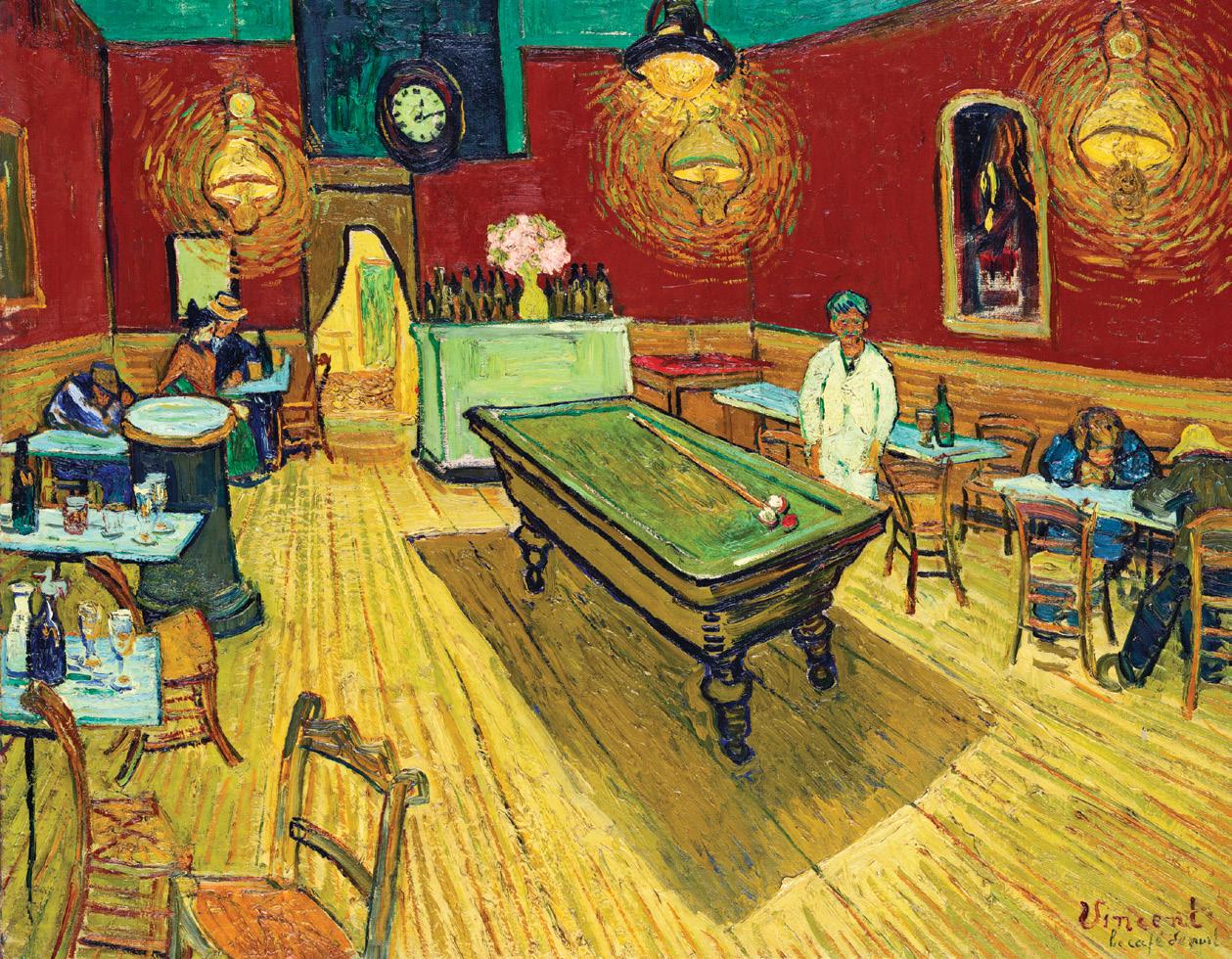

The majority of van Gogh’s bestknown works were produced during the final two years of his life. During the fall and winter of 1888, Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin lived and worked together in Arles in the south of France, where van Gogh eventually rented four rooms at 2 Place Lamartine, which was dubbed the “Yellow House” for its citron hue. The move to Provence began as a plan for a new artist’s community in Arles as alternative to Paris and came at a critical point in each of the artists’ careers. While at the “Yellow House” Gauguin and van Gogh worked closely together and developed a concept of color symbolic of inner emotion and not dependent upon nature. Despite enormous productivity, van Gogh suffered from various bouts of mental instability, most likely including epilepsy, psychotic episodes and delusions. Gauguin left for Tahiti, partially as a means of escaping van Gogh’s

(above) LE CAFÉ DE NUIT (THE NIGHT CAFÉ) Vincent van Gogh (1888). Original from the Yale University Art Gallery. CC0 1.0. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.

(opposite) OLEANDERS Vincent van Gogh (1888). Original from the MET Museum. CC0 1.0. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.

(right) MADAME JOSEPH-MICHEL GINOUX Vincent van Gogh (1888–1889). Original from the MET Museum. CC0 1.0. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.

ROSES Vincent van Gogh (1890). Original from the MET Museum. CC0 1.0. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.

STILL LIFE (NATURE MORTE) Vincent van Gogh (1888). Original from the Barnes Foundation. CC0 1.0. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.

(above) THE POPLARS AT SAINT-RÉMY Vincent van Gogh (1889). Original from The Cleveland Museum of Art., CC0 1.0, Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.

(opposite, top) THE DRINKERS Vincent van Gogh (1890). Original from the Art Institute of Chicago. CC0 1.0, Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.

(opposite, bottom) FIRST STEPS, AFTER MILLET Vincent van Gogh (1890). Original from the MET Museum. CC0 1.0, Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.

increasingly erratic behavior. The artist slipped away after a particularly violent fight in which van Gogh threatened Gauguin with a razor and then cut off part of his own right ear.

On May 8, 1889, reeling from his deteriorating mental condition, van Gogh voluntarily committed himself into a psychiatric institution in Saint-Remy, near Arles. As the weeks passed, his mental well-being remained stable and he was allowed to resume painting. This period became one of his most productive. In the year spent at Saint-Remy, van Gogh created over 100 works, including Starry Night (1889). The clinic and its garden became his main subjects, rendered in the dynamic brushstrokes and lush palettes typical of his mature period. On his walks around the grounds, van Gogh immersed himself in the experience of the natural surroundings, later recreating from memory the olive and cypress trees, irises, and other flora that populated the clinic’s campus.

Shortly after leaving the clinic, van Gogh moved north to Auvers-sur-Oise outside of Paris, to the care of a homeopathic doctor and amateur artist, Dr. Gachet. The doctor encouraged van Gogh to paint as part of his recovery, and he happily obliged. He avidly documented his surroundings in Auvers, averaging roughly a painting a day over the last months of his life. However, after Theo disclosed his plan to go into business for himself and explained funds would be short for a while, van Gogh’s depression deepened sharply. On July 27, 1890, he wandered into a nearby wheat field and reputably shot himself in the chest with a revolver. Although van Gogh managed to struggle back to his room, his wounds were not treated properly and he died in bed two days later. Theo rushed to be at his brother’s side during his last hours and reported that his final words were: “The sadness will last forever.”

Clear examples of van Gogh’s wide influence can be seen throughout art history. The Fauves and the German

Expressionists worked immediately after van Gogh and adopted his sub- jective and spiritually inspired use of color. The Abstract Expressionists of the mid-20th century made use of van Gogh’s technique of sweeping, ex- pressive brushstrokes to indicate the artist’s psychological and emotional state. Even the Neo-Expressionists of the 1980s, like Julian Schnabel and Eric Fischl, owe a debt to van Gogh’s expressive palette and brushwork. In popular culture, his life has inspired music and numerous films, includ- ing Vincente Minelli’s Lust for Life (1956), which explores van Gogh and Gauguin’s volatile relationship. In his lifetime, van Gogh created 900 paint- ings and made 1,100 drawings and sketches, but only sold one painting during his career. With no children of his own, most of van Gogh’s works were left to brother Theo. q

Van Gogh’s Most Famous Paintings

The iconic tortured artist, Vincent van Gogh strove to convey his emotional and spiritual state in each of his artworks. Although he sold only one painting during his lifetime, van Gogh is now one of the most popular artists of all time. His canvases with densely laden, visible brushstrokes rendered in a bright, opulent palette emphasize van Gogh’s personal expression brought to life in paint. Each painting provides a direct sense of how the artist viewed each scene, interpreted through his eyes, mind, and heart. This radically idiosyncratic, emotionally evocative style has continued to affect artists and movements throughout the 20th century and up to the present day, guaranteeing van Gogh’s importance far into the future.

1888

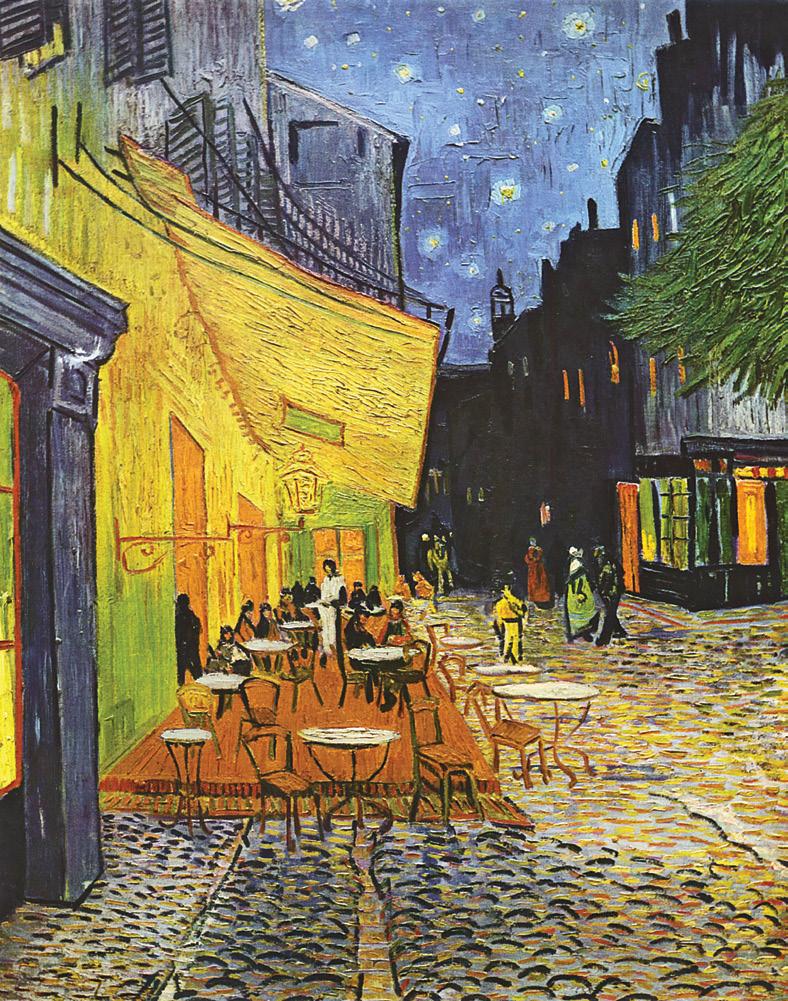

Café Terrace At Night

This was one of the first scenes van Gogh painted during his stay in Arles and the first painting where he used a nocturnal background. Using contrasting colors and tones, van Gogh achieved a luminous surface that pulses with an interior light, almost in defiance of the darkening sky. The lines of composition all point to the center of the work drawing the eye along the pavement as if the viewer is strolling the cobblestone streets. The café still exists today and is a “mecca” for van Gogh fans visiting the south of France. Describing this painting in a letter to his sister he wrote, “Here you have a night painting without black, with nothing but beautiful blue and violet and green and in this surrounding the illuminated area colors itself sulfur pale yellow and citron green. It amuses me enormously to paint the night right on the spot...” Painted on the street at night, van Gogh recreated the setting directly from his observations, a practice inherited from the Impressionists. However, unlike the Impressionists, he did not record the scene merely as his eye observed it, but imbued the image with a spiritual and psychological tone that echoed his individual and personal reaction. The brush strokes vibrate with the sense of excitement and pleasure van Gogh experienced while painting this work. π Oil on canvas Kröller-Muller Museum, Otterlo

Fourteen Sunflowers In a Vase

Van Gogh’s Sunflower series was intended to decorate the room that was set aside for Gauguin at the “Yellow House,” his studio and apartment in Arles. The lush brushstrokes built up the texture of the sunflowers and van Gogh employed a wide spectrum of yellows to describe the blossoms, due in part to recently invented pigments that made new colors and tonal nuances possible. Van Gogh used the sunny hues to express the entire lifespan of the flowers, from the full bloom in bright yellow to the wilting and dying blossoms rendered in melancholy ochre. The traditional painting of a vase of flowers is given new life through van Gogh’s experimentation with line and texture, infusing each sunflower with the fleeting nature of life, the brightness of the Provencal summer sun, as well as the artist’s mindset. π Oil on canvas The National Gallery, London

1888

(opposite) CAFÉ TERRACE AT NIGHT Vincent van Gogh (1888). Oil on canvas, 31.8 x 25.7 in. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

(left) FOURTEEN SUNFLOWERS IN A VASE Vincent van Gogh (1888). Oil on canvas, 37.4 x 28.7 in. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

(below) THE BEDROOM Vincent van Gogh (1889). Original from the Art Institute of Chicago. CC0 1.0. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.

1889

The Bedroom

Van Gogh’s Bedroom depicts his living quarters at 2 Place Lamartine, Arles, known as the “Yellow House”. It is one of his most well-known images. His use of bold and vibrant colors to depict the off-kilter perspective of his room demonstrated his liberation from the muted palette and realistic renderings of the Dutch artistic tradition, as well as the pastels commonly used by the

Impressionists. He labored over the subject matter, colors, and arrangements of this composition, writing many letters to Theo about it, “This time it’s just simply my bedroom, only here color is to do everything, and giving by its simplification a grander style to things, is to be suggestive here of rest or of sleep in general. In a word, looking at the picture ought to rest the brain, or rather the imagination.” While the bright yellows and blues might at first seem to echo a sense of disquiet, the bright hues call to mind a sunny summer day, evoking as sense of warmth and calm, as van Gogh intended. This personal interpretation of a scene in which particular emotions and memories drive the composition and palette is a major contribution to modernist painting. π Oil on canvas Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Van Gogh’s Most Famous Paintings

1889

Starry Night

Starry Night is often considered to be van Gogh’s pinnacle achievement. Unlike most of his works, Starry

Night was painted from memory, and not out in the landscape. The emphasis on interior, emotional life is clear in his swirling, tumultuous depiction of the sky - a radical departure from his previous, more naturalistic landscapes. Here, van Gogh followed a strict principal of structure and composition in which the forms are distributed across the surface of the canvas in an exact order to create balance and tension amidst the swirling torsion of the cypress trees and the night sky. The result is a landscape rendered through curves and lines, its seeming chaos subverted by a rigorous formal arrangement. Evocative of the spirituality van Gogh found in nature, Starry Night is famous for advancing the act of painting beyond the representation of the physical world. π Oil on canvas The Museum of Modern Art

Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear

After cutting off a portion of his right earlobe during a manic episode while in Arles, van Gogh painted Self Portrait with a Bandaged Ear while recuperating and reflecting on his illness. He believed that the act of painting would help restore balance to his life, demonstrating the important role that artistic creation held for him. The painting bears witness to the artist’s renewed strength and control in his art, as the composition is rendered with uncharacteristic realism, where all his facial features are clearly modeled and careful attention is given to contrasting textures of skin, cloth, and wood. The artist depicts himself in front of an easel with a canvas that is largely blank and a Japanese print hung on the wall. The loose and expressive brush strokes typical of van Gogh are clearly visible; the marks are both choppy and sinuous, at times becoming soft and diffuse, creating a tension between boundaries that are otherwise clearly marked. The strong outlines of his coat and hat mimic the linear quality of the Japanese print behind the artist. At the same time, van Gogh deployed the technique of impasto, or the continual layering of wet paint, to develop a richly textured surface, which furthers the depth and emotive force of the canvas. This self-portrait, one of many van Gogh created during his career, has an intensity unparalleled in its time, which is elucidated in the frank manner in which the artist portrays his self-inflicted wound as well as the evocative way he renders the scene. By combining influences as diverse as the loose brushwork of the Impressionists and the strong outlines from Japanese woodblock printing, van Gogh arrived at a truly unique mode of expression in his paintings. π Oil on canvas Courtauld Institute Galleries, London

(top) SELF-PORTRAIT WITH BANDAGED EAR Vincent van Gogh (1889). Oil on canvas, 23.6 x 19.3 in. Courtauld Institute of Art, London, UK, Courtesy of WikiArt.; (above) STARRY NIGHT Vincent van Gogh (1889). Oil on canvas, 29 x 36.5 in. Original from Wikimedia Commons. CC0 1.0. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.

1889

(opposite, top) THE CHURCH IN AUVERS-SUR-OISE, VIEW FROM THE CHEVET Vincent van Gogh (1890). Oil on canvas, 36.6 x 29.3 in. Courtesty Wikimedia Commons. (opposite, bottom) PORTRAIT OF DR. GACHET

Vincent van Gogh (1890). Oil on canvas, 26.3 x 22 in. Courtesty Wikimedia Commons.

Church at Auvers

After van Gogh left the asylum at Saint-Remy in May 1890 he travelled north to Auvers, outside of Paris. Church at Auvers is one of the most well-known images from the last few months of van Gogh’s life. Imbuing the landscape with movement and emotion, he rendered the scene with a palette of vividly contrasting colors and brush strokes that lead the viewer through painting. Van Gogh distorted and flattened out the architecture of the church and depicted it caught within its own shadow – which reflects his own complex relationship to spirituality and religion. Van Gogh conveys a sense that true spirituality is found in nature, not in the buildings of man. The continued influence of Japanese woodblock printing is clear in the thick dark outlines and the flat swaths of color of the roofs and landscape, while the visible brush strokes of the

Impressionists are elongated and emphasized. The use of the acidic tones and the darkness of the church alludes to the impending mental disquiet that would eventually erupt within van Gogh and lead to his suicide. This sense of instability plagued van Gogh throughout his life, infusing his works with a unique blend of charm and tension. π

Oil on canvas Musee d’Orsay, Paris

1890

1890

Paul-Ferdinand Gachet

Dr. Gachet was the homeopathic physician that treated van Gogh after he was released from Saint-Remy. In the doctor, the artist found a personal connection, writing to his sister, “I have found a true friend in Dr. Gachet, something like another brother, so much do we resemble each other physically and also mentally.” Van Gogh depicts Gachet seated at a red table, with two yellow books and foxglove in a vase near his elbow. The doctor gazes past the viewer, his eyes communicating a sense of inner sadness that reflects not only the doctor’s state of mind, but van Gogh’s as well. Van Gogh focused the viewer’s attention on the depiction of the doctor’s expression by surrounding his face with the subtly varied blues of his jacket and the hills of the background. Van Gogh wrote to Gauguin that he desired to create a truly modern portrait, one that captured “the heartbroken expression of our time.” Rendering Gachet’s expression through a blend of melancholy and gentility, van Gogh created a portrait that has resonated with viewers since its creation. A recent owner, Ryoei Saito, even claimed he planned to have the painting cremated with him after his death, as he was so moved by the image. The intensity of emotion that van Gogh poured into each brush stroke is what has made his work so compelling to viewers over the decades, inspiring countless artists and individuals. q π

Oil on canvas Private Collection

Carmel Dawn Oil on canvas, 36 x 48 in

Contemporary Impressionism

9705 Carroll Centre Road, San Diego, CA 92126, (858) 324-4644 San Carlos between 5th and 6th, Carmel-by-the-Sea, CA 93921, (831) 574-1782 www.erinhansongallery.com info@erinhanson.com