KAINAN SA DUWAR FINDING HOME IN A FILIPINO RESTAURANT IN AMMAN BY Olivia Mayeda ILLUSTRATION Olivia Mayeda DESIGN Alex Westfall

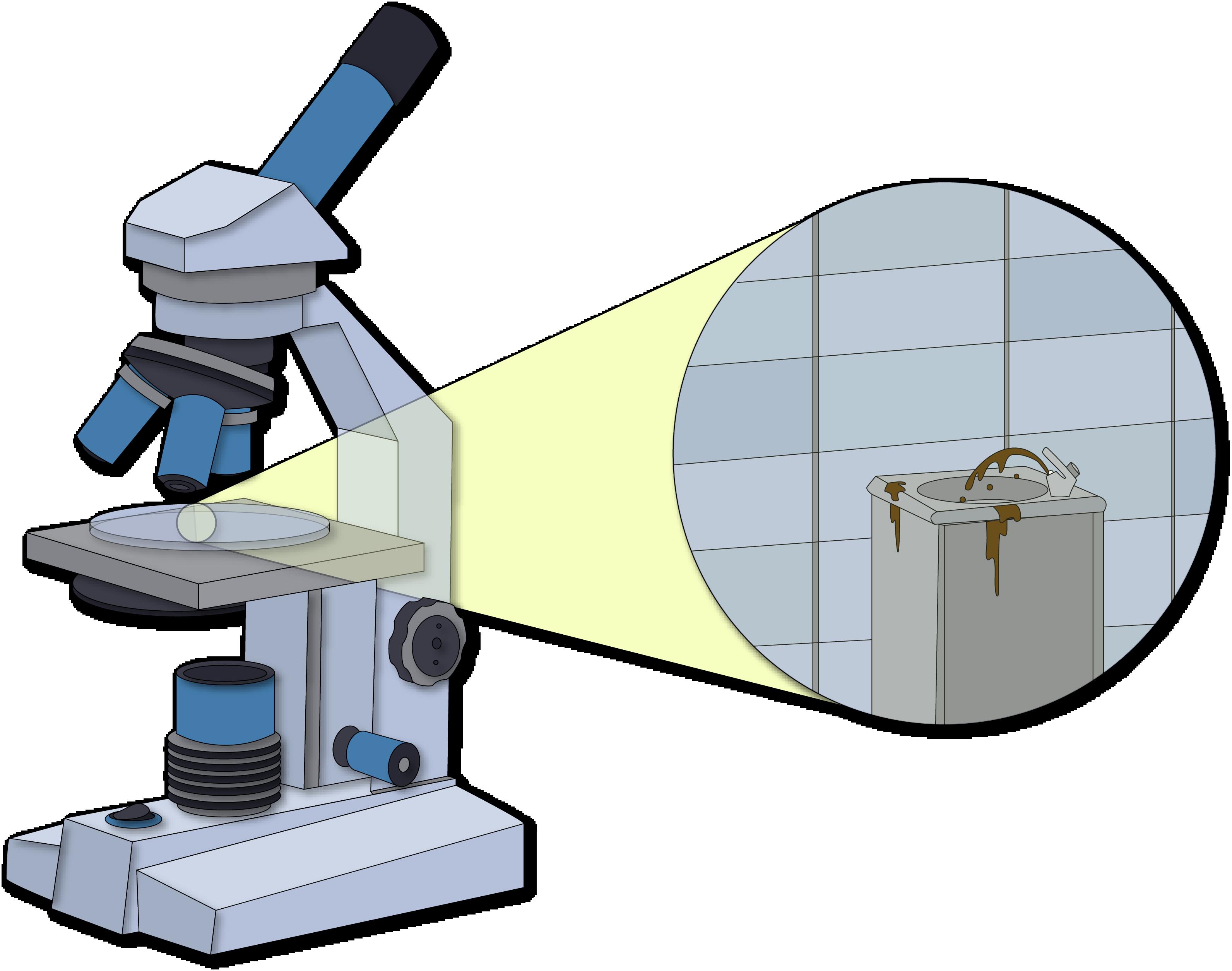

Across the traffic circle, through screens of dust and exhaust, I could see that the long line of sandy buildings met an abrupt end. An empty lot opened up to a rare, sprawling view of the hills of Amman. The sun sat over the earth like a yolk, and I followed it to the vacancy. One month into my intensive Arabic program in Jordan, I decided to explore a neighborhood in Jabal Amman near Second Circle. I was missing home, severely out of place in a program designed for forehead. wannabe CIA analysts and American ambassadors “Kamusta ka?” asked the woman on the other side to fill-in-the-blank country. Meanwhile, I dreamt of the counter, knocking me out of my haze. A golden up new ice cream flavors like miso-candied morrel Fortune Cat sat on the display case, rigid, save for its or labneh chamomile when I was bored in class and right paw, which boxed the air endlessly in anticipation made Palestinian Makloubeh and rolled grape leaves of new customers. with my host mom, Faiza, on the weekends. I watched “Mabute! Kamusta ka?” I responded automatically friends rap and perform slam poetry in Arabic at open with the only Tagalog I knew. mic night at the House of Dreams and rewatched the “Are you hungry?” she asked in English, hearing opening scene of Eat Drink Man Woman when it rained. my accent. She adjusted the fold of her hijab under her When the light turned from frothy yellow to the chin. deep orange of a duck egg, I turned back to the road, “You don’t have halo-halo, do you?” thinking of my parents’ cooking, and encountered a “I’ll make it for you.” second sun. This one had abbreviated rays that termiI asked her how much it was, and she waited nated in round petals. Three buttery stars guarded the patiently while my fingernails dug at the bottom of solar blossom on a triangular void, clasped onto two my backpack picking up grit and paper scraps. I was 85 edges by blue and red stripes. Below, magnified photos qirsh short. of food laminated sliding glass doors. It wasn’t just any “That’s okay,” she laughed, brushing what little sun, I realized, all at once recognizing the pixelated change I had produced from the counter into her palm. plates of food as sinigang, lumpia, and pancit—it was a “Sit.” Filipino one, blooming on the flimsy plastic flag of my She slipped through two hanging canvas panels mom’s birthplace. I followed my feet in disbelief to the dividing the dining area from the kitchen. I sat at a long doors and slid them open. The smell registered first: plank jutting out from the wall. Fraying duct tape lined simmering coconut milk and dried bay leaves and the the edges of the wood, serving no apparent purpose. pungent oil left over in the pan after my grandma fries At the plank in the opposite wall, two women ate from tilapia. I was convinced that some inexplicable portal plates of rice and what looked like dinuguan: a stew of had opened to my grandma’s kitchen in the middle of chili, vinegar, garlic, and pork blood. As a kid, I was the Ammanian hills. ashamed whenever my mom made it. I would mimic Like Grandma’s kitchen, Kainan Sa Duwar was the disgusted expressions of my friends when they smaller than my bedroom on the other side of the came over to our house, horrified by our vampirism, city, cases of coconut milk cans shoved in the back but I grew to appreciate its unrivaled richness over corner. As a kid, I always knew it would be a good day time. at Grandma’s house if I saw those familiar brown and The chef returned with a familiar, psychedelic white labels peeking out of the garbage—a promise arrangement of layers of red and green Jell-o and sweet that coconut milk chicken adobo bubbled in a blue beans on a bed of condensed milk-drenched shaved enameled cast iron pot on her stove. ice nested with a scoop of deep purple ube ice cream, a Displayed in what looked like a recommissioned square of leche flan, and, of course, Rice Krispies. I dug gelato case were tubs of golden battered shrimp, in, excavating each layer one by one, overcome with stewed chicken liver, and whole fried fish towered childlike bliss. The flan was dense, barely jiggling from one on top of the other in alternating orientations like the bowl to my mouth, just the way my mom made it— tempura jenga, the glass windshield so scrubbed and no skimping on egg yolks. scored in a past life to the point of fogginess. Lining the shelves on the walls were kutsinta, the caramelly +++ medallion sticky rice cakes I would sneak from my grandma’s pantry. There was turon filled with banana One of my earliest memories is of resting my cheek on and langka—jackfruit—wrapped in pastry and deep the cold, granite countertop in my parents’ kitchen in fried. When I was six, I crouched on a stool, helping my the summer. Across the counter, my mom, wearing mom fold dough around slivers of brown sugar-dipped slippers taken from a hotel, scooped an overripe banana and langka for my grandpa’s surprise birthday avocado into an old plastic bowl of whole milk. She party, but I was clumsy and didn’t tuck the dough into spooned in white sugar and used a fork to mash the itself properly. I watched the filling bubble out of its creamy avocado meat against the sides of the bowl so wrapper, filling the pot of oil with cinnamon and loose that deep green paste burst between the metal tines. fruit. “Oops,” my mom laughed, kissing me on the “This is what we would have in the Philippines

11

FEATURES

when there was nothing else. Just milk, avocado from the neighbor’s tree, and a little sugar. Here, Olivia, try.” She brought the rim of the bowl to my mouth. The milk was a muted, Hulk green and chunks of avocado stuck to the sides of the bowl, browning from oxidation. My mom, having grown up in a household where abundance was unfamiliar, raised my sister and I not to be picky. I took a sip without hesitation. Fatty, sugary molecules lathered the inside of my cheeks. It was rich and delicious. Afternoons in my grandma’s kitchen in Pinole, one nucleus of the Northern Californian Filipinx community, taught me the intuitiveness of good food. Pork stewed in coconut milk and oxtail served with fermented krill paste were some of my favorite meals from childhood. They were neither simple nor extravagant, but every bit as sumptuous as the fine dining at French or Italian restaurants in the East Bay. There was something just as indulgent about fork-mashed avocado, milk, and sugar as there was about a slab of pan-seared foie gras. Still, when the upscale Filipino restaurant—FOB Kitchen—debuted in Oakland, my parents complained about how expensive it was. The only Filipino food they would pay for was fast food halo-halo and breakfast combos of longanisa sausage, garlic rice, and a fried egg at Jollibee for a grand total of four dollars. “If we’re paying that much we should just go across the street to Pizzaiolo!” my dad groaned at the dashboard one night while we were deciding where to have dinner. There was something about exposed brick and imported prosciutto di parma that put an immigrant family like mine in the mood for 30 dollar chicken. +++ Kainan Sa Duwar turned out to be something of a hub for the Filipinx community of Jabal Amman, and it didn’t pander to anyone. Produce was bought wholesale out of a van that came by every couple days. The woman who had served me was known tenderly by her patrons as Tita Thelma, or simply Ate, a term of respect used when addressing an older woman. Tita had been living in Jordan for over thirty years, and she had four daughters, all studying back home in the Philippines. When I returned two days later, eight men were sitting at the left plank eating shrimp. One of them was a soldier in an exchange program between the Filipino and Jordanian air forces. He was accompanying a fleet of jets on loan from the Jordanian military back to the Philippines in another six months. Another was a company driver, two of them students, here to study the Quran, and the other four were civil engineers.

13 MARCH 2020