BY Andy Rickert ILLUSTRATION Alana Baer DESIGN Alex Westfall

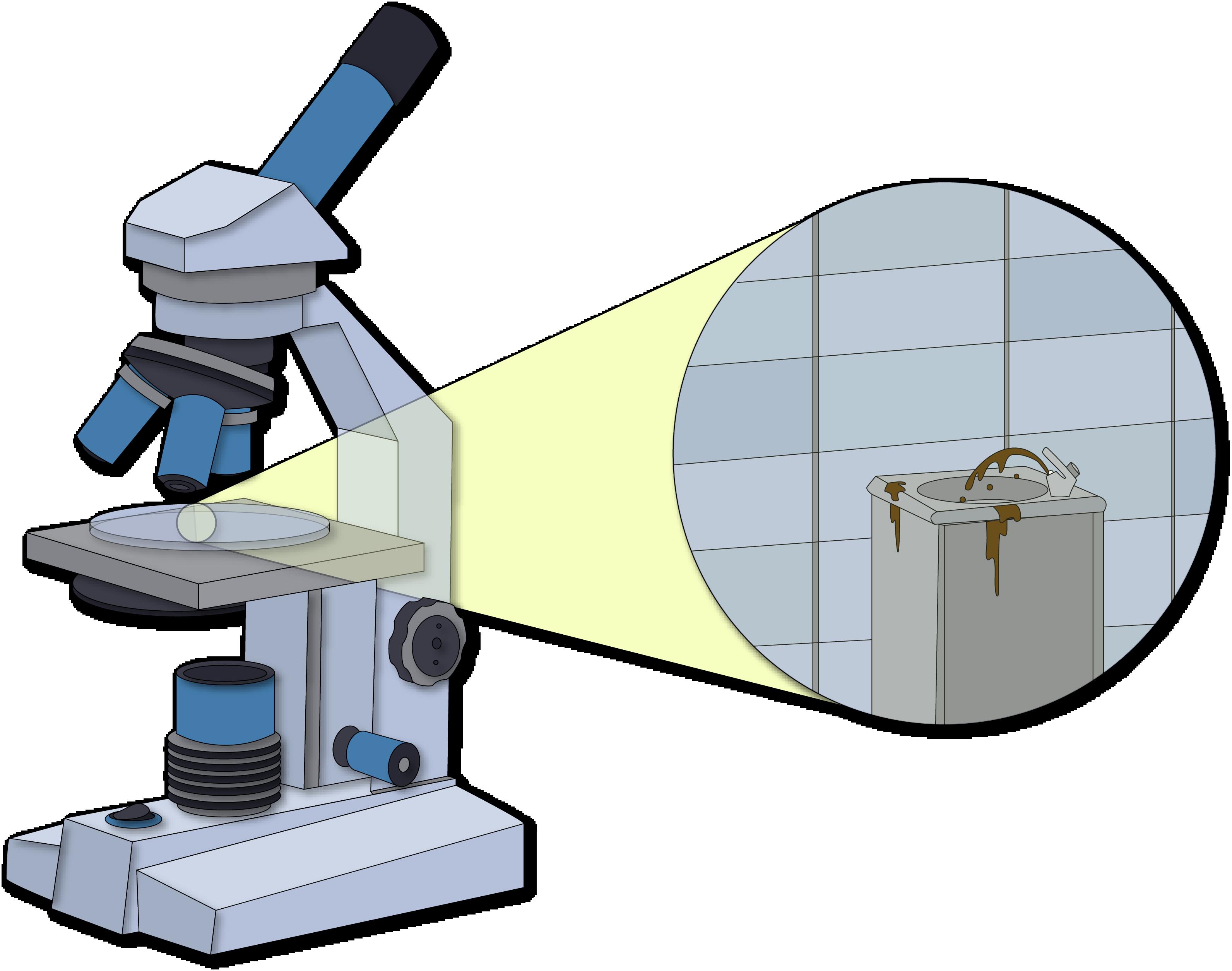

GRIMES, DIGITAL EMBODIMENT, AND THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN LIVE AND RECORDED MUSIC Grimes delivered her performance at The Game Awards in traditional cyberpunk fashion. Hunched over a bulky computer terminal while lasers cast a Tron-like grid over the stage, the popstar borrowed from science fictions of the past to imagine a show in the future. At first, the concert could be mistaken for any other of Grimes’, who boasts a decade-long career making experimental electronic music. However, after the singer dons a headset halfway through the song and collapses into a smoking vat, the performance, it seems, is over. On the monitors behind her, a blue woman in a metallic dress and glowing hair is rendered from the feet up in a vast digital landscape, picking up the show from where Grimes left off. What’s immediately striking is how natural this transition feels. The woman on the screen bobs and twists just like Grimes, while the virtual cityscape below her leaves no desire to return to the physical stage from moments ago. The spectacle of Grimes herself is certainly lost, but the way the camera chases the new figure across its vast digital skyscrapers couldn’t be possible with only her flesh and blood. Shortly after, the avatar turns to dust, and the song fades out. “I think live music is going to be obsolete soon,” said Grimes on the podcast Mindscape. “People are actually just gravitating toward the clean, finished, fake world. Everyone wants to be in a simulation. They don’t actually want the real world.” Music fans’ immediate uproar would appear to disprove Grimes’ sweeping claims—how could something become obsolete that no one is ready to surrender? As headlines like “Grimes Believes Artificial Intelligence Will Make Live Music Obsolete” circulated, fans took to Twitter to express their outrage, with one performer outright calling Grimes “the voice of silicon fascist privilege.” For many, the live concert is a critical part of engaging with any musician’s work. The uniqueness of each show, the physical presence of the artist, and the communal experience of a crowd all culminate in something computers can’t simulate. However, Grimes is far from the first musician to perform digitally. Hatsune Miku, a fictional animated popstar, has been touring worldwide as a digital projection since 2012. At Coachella the same year, a holographic 2Pac performed alongside Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre. Even without embodiment, these performers are able to please a crowd of festival goers all the same. What’s lost in uniqueness is made up for in novelty. Digital bodies are more or less capable of performing just as any human might. Grimes asks if they could ever replace live performance altogether. +++ In 1967, American rock band The Doors stopped playing their instruments in the middle of a live, televised performance. Several monitors had been left onstage, tuned to the channel of their very broadcasting. After turning up the volume, the band sat and watched their own performance on TV on TV, the rebroadcasting of the performance becoming the performance itself. This stunt gestures toward a truth concealed within any mediated culture: the original, essential piece of art is not the event the cameras have been pointed at—it’s the recording itself. Recording is not a foreign presence that captures a live event and distributes it to an audience that wasn’t physically there—the live performance is the recorded performance. The camera is as much a part of it as the guitar. This story runs contrary to common assumptions about live performance, which performance theorist Phillip Auslander helps us understand: “the categories of the live and the recorded are defined in a mutually exclusive relationship, in that the notion of the live is premised on the absence of recording and

13

SCIENCE+TECH

as the live. One of the most iconic album covers in contemporary music, The Clash’s London Calling does not depict the band in Wessex Studios, where it was recorded—its cover features their bassist on stage, smashing his guitar into the New York Palladium. The live allows the studio recording to exist, because it suggests that there is something authentic or real behind an otherwise opaque, mass-produced object. It’s barely a secret that every artist on a major label has a team of writers, sound engineers, and creative consultants. However, rock music depends on the mythology of the live performance as the origin of its art object, even though its origin is a studio. Listeners expect the artist to have written a song to translate their strife into something beautiful; rarely do they sever the music from the body that bears its voice. The mythology surrounding the performer informs the experience of listening. The live concert thus becomes a way to access a mythological authenticity. If a guitarist is unable to perform a solo they once recorded, the musician loses their integrity. For the rockist, the listener who subscribes to this cultural mythology, the live is where performers can’t hide behind the facade of autotune or 30-person writing teams. Without an unmediated live, there would be no way to know whether the talent behind the record is real. The binary of live and recorded can thus be theorized in terms of Baudrillard’s simulacra, in that both parts of the binary are “conceived from the point-of-view of their very reproducibility,” resulting in a “reversal of origin.” Neither the record nor the performance are “real”— both are artificial and point to the other as its origin. This blame game produces its own reality that is both independent from and dominant over its audience; a play of signs called simulacra. This simulated reality can be unweaved when the rules it defines for itself are revealed as arbitrary or merely referential. At a concert, tools like autotune break down the binary between live and recorded by suggesting that there never was an authentic origin to the art piece—it was always artificial. In the rockist mythology, all forms of technology threaten authenticity because they mediate the presence of the performer, allowing for deception. Of course, a tool like autotune can be employed deliberately—that is, without the intent to obscure—just as Jimi Hendrix might use an electronic pedal to create a new sound from his guitar. Therein lies the arbitrariness of the opposition of live and recorded: it’s not that the live can’t be mediated by technology to still be considered live, it’s that a specific threshold of mediation has been culturally constructed, and varies from generation to generation. Up until a certain point, the live artist can appropriate technology and still be authentic. Whether it’s Bob Dylan going electric or a hip hop MC rapping over a sample, the appropriation of technology into live performance has always threatened the fictional authenticity of the live, only to eventually become the status quo. Grimes’ performance and comments on Mindscape mark the most recent iteration of this trend. If the performer onstage is a digital body, then everything about the performer’s image is thrown into question. How can we locate the origin of the song on the record without a voice, much less a body to place it onto? The ability to verify the physicality, much less the entire existence of the popstar, is lost. Of course, this has always been the case behind the thin curtain of simulacra—a name on an album has never needed to point to a living person in order to have a page on Spotify. Digital performance could set us free from +++ this limiting narrative of authenticity, but its audience The origin of the rock record as a world of its own would first have to be ready to let it go. becomes obscured under the mythology of its origin

the defining fact of the recorded is the absence of the live.” Under traditional assumption, liveness implies spontaneity and authenticity, whereas the recorded is more contrived or artificial. The live performance is a moment when the audience can access the unmediated performer, without the meddling of sound engineers or the opportunity to redo a take. Upon further inspection, this binary breaks down; technologies of recording have mediated the way audiences experience performance from the introduction of the modern rock record. This false opposition plays a crucial role in weaving the mythology of the artist, both in the popular imagination and in the music industry itself. Auslander describes how common understanding maintains that “the live event is ‘real’ and that mediatized events are secondary and somehow artificial reproductions of the real.” In this case, the assumption would be that The Doors’ concert is the origin of their art product while the record is a mass-produced recreation. While The Doors challenged this assumption by placing a recorded event within a live event, such that the live event very literally became its own reproduced depiction, this binary had been threatened from the very beginning of the rock genre. Whereas a jazz fan attends a performance to see a unique improvisation, or a classical listener evaluates the success of a performance through paper scores from the 17th century, the original, essential object for the rock listener, with few exceptions, is the studio record. Pre-rock genres are certainly recorded and mass produced in the same market as rock, but the content of these records is not predicated upon the act of recording. An art object exists outside of these records. Classical records always distinguish a specific orchestra performing a specific symphony—one recording never claims to be the definitive version of Beethoven’s Fifth. Although jazz records might not make this distinction in their title, the unique, singular recording session that constitutes an album like Coltrane’s A Love Supreme informs the listening experience. The recording does not insist upon its own reality; it still points to a specific moment or event. For rock, however, the studio album is its own world. Abbey Road is not a recording of something that happened; it doesn’t capture something that exists independent of it—Abbey Road is Abbey Road. Its iconic cover and audio mastering are just as much a part of Abbey Road as the music itself. To witness John Lennon perform “Octopus's Garden” is not to encounter the original piece of art in the same way one might see the Mona Lisa in person after only encountering reproductions on a postcard or on a TV program. For the rock album, the mass-produced object is the original art, and the performance is a reproduction of the recording. The success of the record is not gauged by how closely it mirrors the live show. Instead, the success of the live show is gauged by how closely the performer can capture the essence of the record. I first saw Grimes at a music festival after my freshman year of high school. I don’t remember much, other than how badly I wanted to hear “Genesis” performed live. Every time the audio faded between songs, I got excited all over again thinking the next track would be “Genesis.” When she finally closed with it, everything around the song made it incredible; the backup dancers, the massive fan blowing her hair every which way. “Genesis” sounded great live, but it was performed nearly identical to the studio recording. What made the performance special was the context, not the content of the song.

13 MARCH 2020