The female ghosts in Portrait of a Lady on Fire

BY CJ Gan ILLUSTRATION CJ Gan DESIGN Ella Rosenblatt

The vocabulary of film discourse contains a rather reductive palette of praise, one critics love to slather on every striking work that emerges. A selection from reviews of Celine Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire is revealing: “A hauntingly intimate vision of love.” “A haunting, erotic, and evocative period piece.” “Hauntingly beautiful.” It’s a strange turn of phrase. The question to ask of a ‘haunting film’ is—who is being haunted? And who is the one haunting? For when we speak of haunting, we evoke the figure of the ghost, the specter of the dead, or, put another way, the presence of an absence—something gone but not quite disappeared that lingers on. +++ Portrait is set in eighteenth century France, on a remote, quiet island off the coast of Brittany. Marianne (Noémie Merlant), an artist, is tasked with the job of painting a portrait of Héloïse (Adèle Haenel), a young aristocratic woman, which must first be sent to her suitor in Milan for his approval before their marriage can proceed. This affair is arranged by her mother, the Countess (Valeria Golino), but Héloïse is reluctant to give up her freedom and marry a man she does not know, and so refuses to sit for her portrait; when Marianne arrives, she has already exhausted th efforts of a previous painter. Marianne must thus pretend to be her companion for walks while secretly observing her for the painting. After establishing this premise, the film breathlessly unravels. The two of them are inexorably drawn to one another; when the subterfuge is inevitably revealed, Héloïse coldly criticizes the portrait and Marianne tearfully grabs a cloth and smears the still-wet paint, destroying the face. However, upon seeing the ruined portrait, Héloïse abruptly changes her mind and agrees to pose for a second portrait. The Countess must leave for the coast of Brittany, and in the absence of her controlling presence, Marianne and Héloïse’s attraction grows—but when the painting is finished and the Countess returns, Marianne must leave. They will never meet again, yet they see each other everywhere. This is not a spoiler; the events of the film unfold without surprises or twists, almost foregoing a conclusion. In this film, it is not what happens inasmuch as how it happens, not what is shown but how it is shown— and how it is not shown—that captivates. There is an invisible thing in this film that reveals itself without being shown; that is unspoken and yet ever-present. Marianne and Héloïse’s queerness is never explicitly discussed, never once drawn to our attention as something special or extraordinary. There is never even a mention of them loving one another, an almost necessary cliché of heterosexual romantic stories—though there is a more general discussion of love, it refers only to heterosexual relationships. There are no words for what they have in a linguistic discourse in which only heterosexual relationships are condoned. Moreover, there is no need for any word for it; it resists the very act of being named. Because to name it would be to mark it as different, as an object upon which meaning can be inscribed, something that must be explained, made sense of, contained. There are no words for this haunting presence. It merely is. Throughout the course of their romance, Marianne is literally haunted by the vision of Héloïse—a pale, glowing form clothed in white, foreshadowing the agonizing moment of her departure. This surreal interjection in the film is complicated by the temporal framework of the entire film, which unfolds as a flashback in present-day Marianne’s mind. Perhaps this ghostly apparition is Marianne’s knowledge of what will haunt and taint her memories of what came before. Or perhaps it is truly something seen by Marianne in the past, the premonitory omen of a fate she knows is

07

ARTS

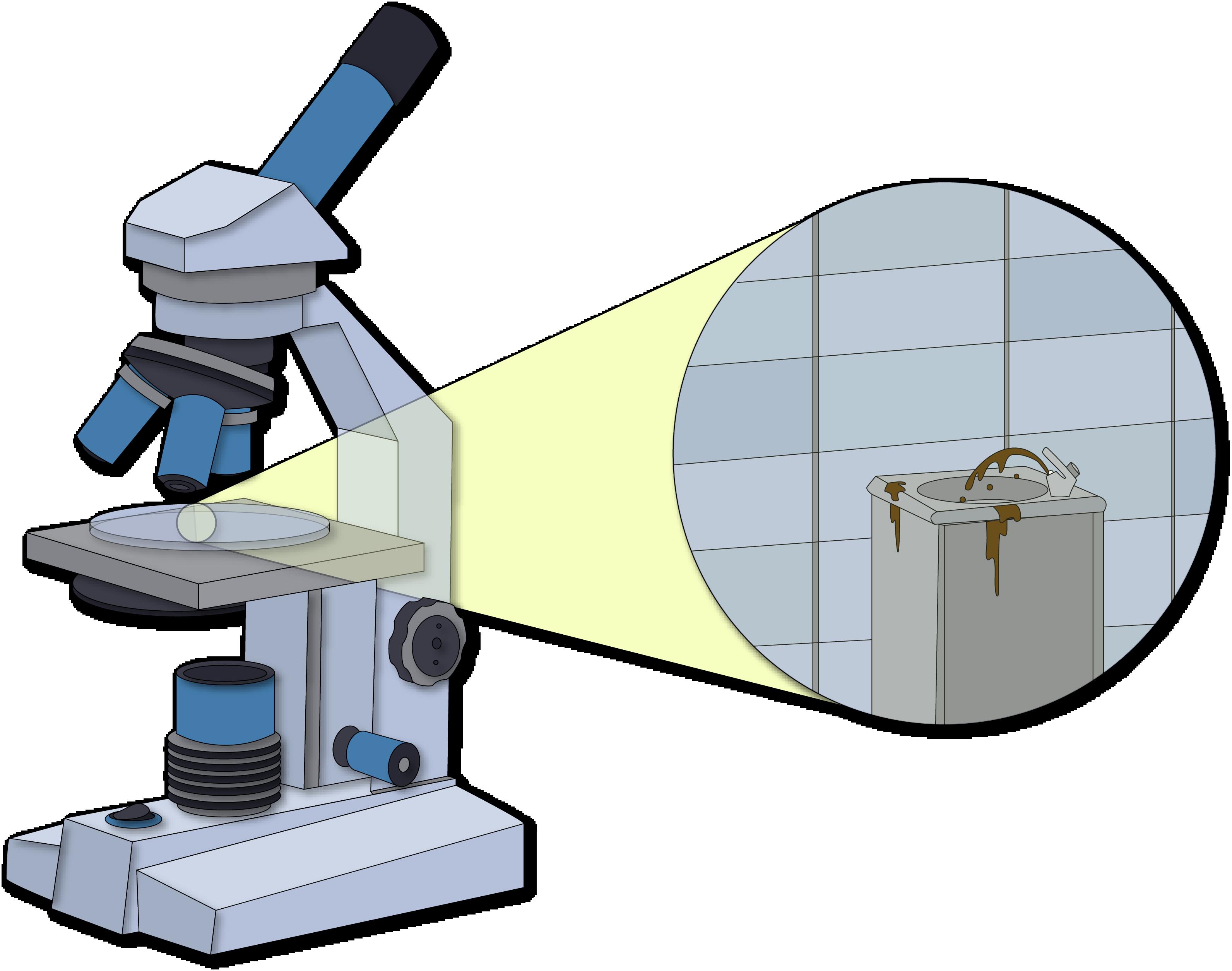

non-being. Power haunts as well, and its ghost does not stay silent forever. It lurks in the shadows, biding its time, only to suddenly, shockingly, lunge into vision, when Marianne wakes up after her last night with Héloïse, walks into the kitchen, and sees a man sitting there. At this moment, you realize that since the fourth minute of the film, for almost the entire runtime, you haven’t seen or heard a single man. It is a chilling moment in which the world that the two women have built for themselves abruptly crumbles. The man in the kitchen is tantamount to a ghost appearing in a horror film—as Sciamma herself put it in an interview with Vox; the “jump scare of patriarchy.” Even though we only see this patriarchal ghost near the end of the film, it’s evident that it has been haunting this place for a long time. It was waiting for the Countess when she first arrived on the island decades ago. She grew up in Milan; her parents arranged her to be wed to a nobleman living on the island, and sent her portrait ahead to be vetted by her husbnd-to-be. Stepping into the house for the first time, she looked above the fireplace and saw the portrait staring down at her. “She was waiting for me,” the Countess tells Marianne. The haunting gaze of this marital portrait is reincarnated in the portrait that Marianne must paint of Héloïse. Both are intended not for the sitter but for a ghostly presence who controls the image without being there: a man who appraises the woman and judges if she is beautiful enough to marry. The gaze inhabits Marianne too. The Countess’ marital portrait was painted by Marianne’s father; she inherits not only his trade as a painter but also the male +++ gaze inherent within his art. Thus, when Marianne But the figure of ghost is not only a vessel for first attempts Héloïse’s portrait, the image is lifeless: marginalized identities to speak against erasure and her face plastered with a faint, sickly smile so cold and

inescapable. Perhaps their romance cannot last—but that does not mean that it dies. It lingers, even if unseen to all but them. That is the imperative that they lay down to one another: Remember. Do not forget. Black queer feminist Sharon Holland once said that “Bringing back the dead…is the ultimate queer act.” The erasure that society enacts upon non-normative sexualities relegates them to invisibility and non-being. To cling onto haunted memories is to allow that which society condemns to death to live on. Earlier in the film, Marianne, Héloïse, and Sophie discuss the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice—how in turning to look back at her on the trek out of hell, Orpheus chooses to sacrifice his future with his wife to preserve one final perfect memory of her. Héloïse, in a flash of insight, says, “Perhaps she was the one who said, ‘Turn around.’” So as Marianne flees from the house, unable to bear what she must do, Héloïse, as Eurydice, commands Marianne to turn back. Sciamma resists the temptation to enact a wish-fulfilment fantasy of queer relations persevering and blossoming against all odds, just as Orpheus ultimately cannot save his lover from hell. But she also denies the tired trope of queer love as a fatalistic tragedy. She rethinks the binary of queer narratives and posits a new way that love can live beyond its death. Heeding Héloïse’s command, Marianne looks at her one final time. As their relationship dies, a ghost is born.

13 MARCH 2020