16 minute read

Metro

The institutional harms caused by Brown’s Office Of Residential Life

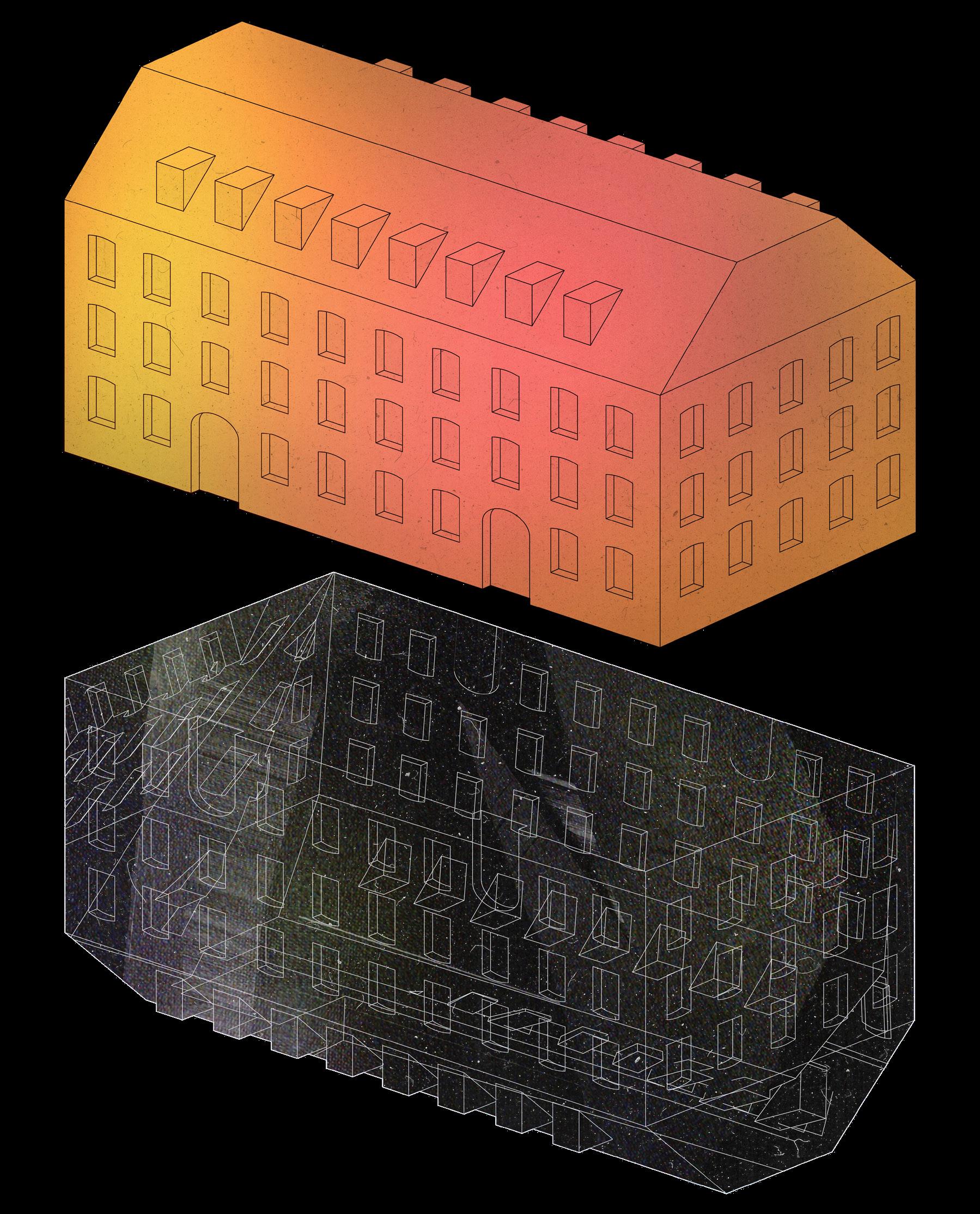

BY Mira Ortegon ILLUSTRATION Mara Jovanović DESIGN Audrey Therese Cabrera Buhain

Advertisement

content warning: sexual assault

Paint peeling down the walls, a broken heating system, and mice scampering under the bed. As many college students know from experience, the physical conditions of on-campus residence halls can range from disappointing to unacceptable. Brown University is no exception. Jason Carroll, Vice President of Brown University’s Undergraduate Council of Students (UCS) in 2019–2020, told the Independent that the most frequent type of complaint that students brought to UCS in the past year had to do with on-campus housing or the Office of Residential Life. Students have experienced heating and cooling issues, vermin problems, discolored water flowing from the tap, and mold that makes them sick. These issues have even garnered national attention—the New York Times featured a Brown student who developed a heat rash and pain after mold grew in her humid, uncooled dorm room.

When asked to comment, Brian E. Clark, a spokesman for the University, assured the New York Times that this was an isolated issue. Clark rejected the idea that unfit dorm conditions are a pattern at Brown, pointing to yearly room inspections and the University’s paint program. Carroll echoed the sentiment that the University maintains upkeep of residence halls through the Summer Restoration Fund. The Fund allows Brown to perform repair work on 1–2 residence halls each summer, and focuses on the bare essentials, such as a dorm that needed a new roof last summer.

The University has also taken larger steps that reflect its recognition of persistent issues with on-campus housing, recently announcing plans for two new residential communities to alleviate the increasing need for updated on-campus housing. On some issues, students have successfully advocated for changes in residence halls. Carroll explained that broader concerns that affect the health and safety of large swaths of students are the types of issues that UCS can and does make traction on. Carroll himself created a buzz on campus after he brought bottles and bottles of brown water from the tap of on-campus residence halls located on Wriston Quadrangle to one of his UCS campaign events. In Carroll’s time as VP, UCS has successfully leveraged its frequent meetings with administration and staff in the Office of Residential Life to convince Brown to replace all of the water tanks in the dorms located on Wriston Quad.

While the reception to addressing physical dorm issues is positive, Carroll said that the UCS also receives complaints that it doesn't have as much ability to advocate for. Regarding individualized student complaints concerning mental health or accessibility, the UCS protocol refers students to the appropriate resources on campus, like Student and Employee Accessibility Services (SEAS), Sexual Harassment & Assault Resources & Education (SHARE), and the Office of Title IX. These offices then advocate for students and work with the Office of Residential Life to find appropriate solutions.

But what happens when students have support from the appropriate resources but are ignored by the Office of Residential Life? While dorm conditions are a highly visible manifestation of the issues with Residential Life happening at the University, there is also a dark underbelly of harmful experiences that students have had with the Office that are not as visible. Feeling safe, comfortable, and happy where one lives is a fundamental factor of being a successful college of Residential Life lacks an effective mechanism student. Combatting issues that undermine this to deal with these individualized cases related to environment should be a priority for Brown’s Office mental health. After surviving sexual assault during of Residential Life, but the University lacks a formal her first year at Brown, Jamie now has panic attacks mechanism for addressing such issues. when she sees her assaulter around campus. These

When asked to comment on how the Office of panic attacks are so draining that Jamie is sometimes Residential Life handles issues related to disability, unable to attend class, instead returning home to mental health, sexual assault, and more, Koren sleep for the rest of the day. As she began to process Bakkegard, Vice President for Campus Life, told the the experience during her sophomore year, Jamie Independent that “Residential Life works with many realized that she needed to reach out to resources on partner offices and processes to support and respond campus to get support. When the housing lottery for to students’ needs.” While Bakkegard did not provide junior year on-campus housing came around, she a more detailed explanation of the Office’s protocol, had already been in touch with Advocates from the she did say that “where there is such an intersection Sexual Harassment & Assault Resources & Education between a student’s needs and a change in their room (SHARE) office. Alana Sacks from SHARE worked configuration, room assignment, or room condition, with Jamie to reach out to the Office of Residential then staff in Residential Life work to address those Life. Given how debilitating these panic attacks were needs in a timely and responsive way.” when Jamie was out on campus, it was clear that she

Despite the University’s purported commitment to could not live in the same on-campus dorm as her supporting students experiencing a variety of complex assailant without a deeply negative impact on both her issues, students continuously share stories that paint academic performance and personal well-being. Even a very different picture. Students have provided with a SHARE Advocate, a professional employee of accounts of reaching out to the appropriate resources Brown’s administration, on her side, communication for help navigating poor housing situations that were on Jamie’s behalf was largely ignored. Alana had to call negatively affecting their mental health. Though four people within the Office of Residential Life before students carefully followed the necessary protocol, the she could even discuss the situation with them. Office of Residential Life ignored calls and emails, laid Jamie had hoped that the Office of Residential the burden of these problems on the shoulders of the Life would ensure that she and her assailant did not already struggling students, and exacerbated mental pick the same dorm location for junior year. The Office health crises. of Residential Life told her that all she could do was

When Elena* was a sophomore at Brown, she and enter the housing lottery like everyone else, and once a friend were living in a two-bed room on Wriston all the rooms had been selected, the Office would tell Quad. They had mutually decided that they needed to her whether or not he had selected the same building move out of their double and into single rooms—while as her. “It boiled down to the fact that if I picked the they remained friends, the housing situation was same housing group as him,” Jamie explained, “I was not working for either of them. Elena was not getting the one who had to make the decision to leave.” The enough sleep and was experiencing high levels of Office of Residential Life wouldn’t tell Jamie where her anxiety, so she reached out to SEAS and got approval assaulter lived, just whether or not he lived in her dorm. to move out of her room once a single became available This meant that he could live in the dorm next door, on campus. The uncertainty of the situation was frusor in a dorm where Jamie frequently visited friends, trating, though, and Elena attempted to get in contact without her knowledge—leaving her in constant fear of with the Office of Residential Life in order to ask about seeing him. the chances of a room change, as well as the process The Office cited confidentiality as the reason not to and the timeline. Despite reaching out to various disclose the dorm that Jamie’s assailant had selected. members at the office, weeks went by without commuThere is certainly a valid legal constraint there, but nication, and the lack of support amplified Elena’s where students live at Brown isn’t really a secret. anxiety. She began looking for her own solutions and Names are tacked to doors with playful sticky notes, eventually came across two students who lived in and students know their hallmates; unlike health single rooms and wanted to switch into her double. information or financial status, the living situations

When she emailed the office with this information, of students on campus is largely public information. a staff member replied immediately and approved the Without sharing the information with Jamie, it felt like plan as long as all four students were willing. Even so, the Office of Residential Life placed that burden—and after all the students had confirmed their approval, all of its consequences—on her shoulders. “That was a Elena got no response from the Office of Residential lot of what I noticed,” Jamie told the Independent. “Any Life for a week. It wasn’t until her parents, who are time I reached out for resources or help with the situalawyers, called the Office and pressured them to act] tion, it was pretty much like ‘Well, you figure it out. If that Elena and the other students were able to carry this is something you care about, this is your problem.’” out the move. The process, initiated in the beginning of November, dragged on until mid-December, forcing +++ the students to switch dorms during finals period.

“When it comes down to it, they [the Office of Despite the fact that Jamie had professionals Residential Life] need to have systems in place that within the Brown community advocating for her, her can handle these types of situations,” Elena told the needs were not met by the Office of Residential Life. Independent. “I was lucky because Brown was made for This was extremely disappointing for Jamie, who said students like me, a student with lawyer parents from that having a safe and comfortable living situation is Massachusetts. But the majority of Brown students a crucial and foundational element of everything else don’t have parents that are capable of making a phone she does on campus. This negative housing situation call in the middle of the day to tell the Office ‘My further intensified the existing challenges that she daughter has anxiety and you are actively harming her was dealing with. “A lot of the support I needed after mental health by not responding to any of the emails experiencing an assault boils down to autonomy and that she has sent.’” control and feelings of safety, and a lot of autonomy,

Even though things worked out for Elena in the control, and feelings of safety come back to where you end, her success was a byproduct of her relative privilive,” said Jamie. “To not have the autonomy to be able lege, and the process still felt deeply unsupportive. Her to say ‘This is how I want to live in a space and this is living situation induced stress, and the responsibility what I want it to look like,’ and the safety of knowing of having to find a solution herself compounded that that I had a space of my own that I felt comfortable in stress. After she moved into a single, she reported that made being on campus feel like a nightmare.” sleeping better and feeling comfortable in her home In order to ensure that her assailant would not be made her significantly more productive and happier. in her living space, Jamie ended up having to sign an Without her parents' help and her own advocacy, Elena informal complaint with Title IX, which required the would likely have been unable to move at all, potenTitle IX Coordinator to sit down with her assaulter tially spending all year in a negative environment. and request his agreement to avoid her dorm. In order

Jamie* echoed Elena’s concern that the Office to file the agreement, Jamie had to give up the right

to file a formal Title IX complaint, meaning she was essentially giving up the right to hold her assailant accountable and receive justice while at Brown. The process Jamie endured in order to satisfy her shortterm needs—a home she felt safe in—fundamentally preserved the power differential between her and her assailant. The assailant got to choose whether or not to comply with the informal Title IX agreement to avoid her dorm, while Jamie had to give up the right to formally file a report against him. This experience was deeply damaging to Jamie, who had believed that Brown was a place with accessible resources that students wouldn’t have to fight for. She felt like Brown didn’t care about her.

At the highest level, the problem that Jamie identified was that the Office of Residential Life has no formal procedure to deal with situations that threaten students’ mental and physical health. These student issues don’t gain critical attention because of their highly personal nature; outside of this anonymous article, the only way Elena or Jamie could have gained widespread support would be to publicly share their personal experiences. While it can be easy to complain openly about the mold in your room and join together with other students, the stigma and legitimate privacy concerns surrounding mental health and sexual assault render these individual student experiences invisible.

The reality is that there are likely many more cases like these at Brown—one student even responded to my request for an interview and later declined to participate because they were afraid to antagonize the Office of Residential Life any further. The impact of institutional neglect in the Office of Residential Life is surely felt by many students, but the students who are most detrimentally affected are those who are already facing structural inequalities. The stakes of a housing arrangement are far higher for students who hold marginalized identities, are low-income, and/or are undocumented—especially at a university with a body of students as wealthy and well-connected as Brown’s. The University’s reluctance to sufficiently address student needs exacerbates the intersectional oppression and emotional trauma that these students are already subject to on campus. Even further, students who hold marginalized identities often lack the access and resources needed to advocate for their legitimate concerns, while wealthy students have reportedly used connections to powerful University Trustees like Marty Granoff to “bypass university processes and gain better housing from the Brown Office of Residential Life.” It is crucial to consider the Office of Residential Life’s role in further entrenching these glaring inequalities.

What can account for these negative experiences with the Office of Residential Life? Is it true that Brown doesn’t care about students who are struggling with their mental health? In response to my email laying out the subject matter of this article, Bakkegard wrote: “I must reject the implication that students’ legitimate needs are disregarded by the Office of Residential Life. The professional staff members in Residential share a commitment to ensuring that our residence halls provide students with healthy, safe, and comfortable

Residential Peer Leaders expressed significant their jobs descriptions and reported that the departStudents and Acting Senior Director of Residential Life at the time. Given that the Office’s website currently lists vacancies in four out of five Area Coordinator positions, it seems that the Office of Residential Life has not been at full capacity for at least four years, or the entire student tenure of Brown’s cClass of 2020. Bakkegard conceded that the professional staff has vacancies but did not go so far as to respond to the

places to live and study and that our operations and Independent’s question of whether or not this impacts processes are fair and responsive to students’ needs.” the Office’s ability to carry out its work.

Clearly, there is a considerable disconnect between Another component of the problem could be the Office of Residential Life’s ostentible commitment the fact that there is no formalized procedure for the to student wellbeing and the actual lived experience of Office of Residential Life to take student feedback into students at Brown University. While the administraaccount. In response to my questions about the process tion's intent may be to support students, Residential by which students should express their housing needs, Life is a heavily bureaucratic system in which students’ Bakkegard suggested that students report physical needs often fall through the cracks. To continue to dorm issues to Facilities Management. She recomdismiss the claims of students and shirk accountability mended that students experiencing mental health for harmful housing situations is neglectful on the part challenges speak with their Residential Peer Leaders, of the University. who would connect them with resources from offices

This issue is perhaps attributable to understaffing, like Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS). something the Office has struggled with for years. Students with disabilities must seek out housing The Brown Daily Herald published an article in 2018 adjustments through the SEAS office. When students followed the exact processes Bakkegard described, however, their communications were ignored and their needs neglected. Their experiences of deep personal harm became invisible. The solutions Bakkegard provided are vague and place the burden of responsibility on other offices within Brown University. This decentralized, bureaucratic system hinders institutional change, as students are not able to make their voices heard. The root cause of this issue is not clear, and the University’s Office of Residential Life did little to elucidate that. My repeated emails to multiple staff members were ignored for weeks, until Bakkegard finally responded. Rather than conduct an interview with me, she asked for a list of questions and answered only a handful of them. My attempts to follow up—even for seemingly innocuous questions on statistics—were also ignored. What has become clear is that the University’s Office of Residential Life needs to take a concerted, critical look at their processes and impact on student experience. The Office’s Mission Statement affirms the following: “The Office of Residential Life fosters a safe and inclusive living environment that promotes student learning and holistic development by providing tools to help students navigate the social, emotional, and academic elements of their residential experience.” Brown must recognize the fact that their lack of action to address student housing needs actively discussing the problem of retaining a full staff in the mental health crises, compounding structural inequalOffice of Residential Life. According to the Herald, ities, and ultimately threatening the holistic wellbeing three community directors and Kate Tompkins, the of the student body. A purely discursive commitment Associate Director of Programs, left the already underto support students does more to undermine students’ staffed Office of Residential Life in the summer prior claims of harm than to reduce actual instances of harm. to the 2018–19 school year. The remaining two commuThe Office of Residential Life should stop writing nity directors and one associate director each worked empty statements and instead focus on creating new double duty while also relying on student Residential systems of accountability-- —systems that are transPeer Leaders (similar to a typical university’s parent, center student experiences, and actually mitiResidential Advisor, or RA) to carry the extra weight. gate harm.

concerns over taking on extra responsibilities outside *Names have been changed for anonymity. ment had been understaffed for at least two years. This MIRA ORTEGON B’20 has left her own ResLife was confirmed by Mary Grace Almandrez, Dean of woes far behind her. hurts their students, exacerbating