3 minute read

Science+Tech

“I knew everyone there cared for me even as they shoved me,” I said.

“That’s crazy,” she said.

Advertisement

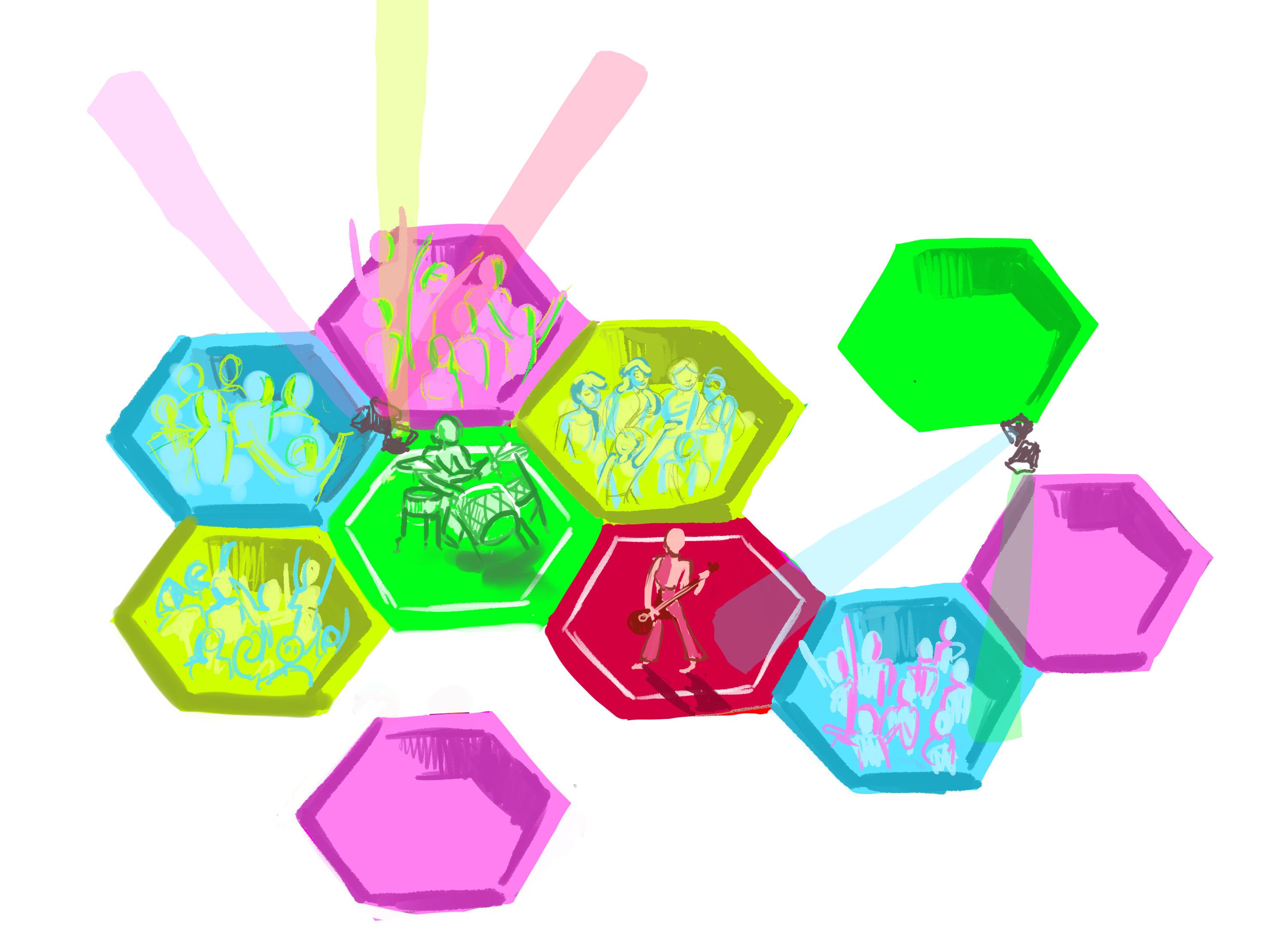

+++ Another concert showed me what it means to mosh without love. The band: Lightning Bolt. The crowd: untrustworthy. I saw five crowd surfers crash to the floor from a lack of supporting hands. Shovers did not account for the shoved. I didn’t realize what I had at the IDLES show until I was flung into an elbow and received no apology.

Since the IDLES show, I’ve moshed at dive bars with tiny crowds huddled around unknown bands. I’ve moshed with art school kids who strained to shove me across the room. I’ve moshed with assholes who shoved anyone around them, whether they wanted it or not. The Lightning Bolt mosh pit was the most dangerous. At its worst, a mosh pit is a too-masculine, too-violent space for people who want to shove.

At the Lightning Bolt concert, shirtless punks claimed the territory short kids needed to see anything on the stage. Anyone who did not want to mosh was forced away from the front of the crowd. I saw many men and few people of other genders. My hands grazed the shoulder or chest or butt of a stranger who did not want to be touched there, but couldn’t fend off the writhing crowd. I rolled my ankle and limped away from the center. As I limped, I was still pushed. To mosh, a body must surrender to the crowd.

It is a privilege to donate your body to the masses for fun.

It is a privilege to seek the fringes of violence for fun.

I have known these privileges. I am a genderqueer person who grew up as a man for most of my life. This privilege feels distinctly male and white. A body without a societal history of harm may give itself to chaos more readily than other bodies. Thrill-seeking seems most desirable to those with fewer bodily concerns to contend with on a daily basis. Men (white men in particular) are not socialized to fear the hands of the public.

I don’t believe it is wrong for people to seek spaces in which they may enjoy safe expressions of near-violence, but I take issue with the exclusivity of these spaces. It saddens me that I enter every mosh pit with fear that I might be pushed a little harder because of my brown skin or eyeshadow. I take issue with the many power dynamics which prevent women and femmes, people of color, queer people, and more from surrendering to the pit. Mosh pits have provided me with near-perfect experiences of bodily intimacy. I want these experiences to be available for all who seek them. I want my body, each body, to melt into the crowd without trepidation.

+++ At the ice cream shop, my other coworker Charlie rushed in and said, “Be careful around Boston Common. My partner and I were just queer-bashed by some assholes.”

“Are you OK?” We, the chorus, sang. “Oh I’m fine. But my partner got a nasty bruise.” +++ Despite its shortcomings, I have faith in the mosh pit. Compassionate mosh pits could be oases of care for those who want it. In a world which promises no safety for many bodies, mosh pits could grant curated bodily experiences. People can consent to pushing and nothing else, then experience pushing and nothing else. I believe the pit can grow to include those who are not included yet. With more bands like IDLES, more disciples of compassion in the punk scene, we can redesign moshing around love.

Let the mosh pit expand to accept everyone who needs it. Let each body, whether in the pit or not, achieve ecstasy. Let the pit in all its nonviolent violence and care decry all forms of bodily harm. Let the pit pour into itself until each water molecule has loved its journey. Let it undulate. Like a body. Like a promise. Let it redouble its effort to stop violence from travelling anywhere else. Let the pit’s edges be the walls of a wave pool, where water can crash without splattering the world. Let this be the upper limit of our violence, the lower limit of our joy. Let us all dance until we bike home safe. JAIME SERRATO MARKS B'20 likes to collide with others.