4 minute read

T A Reflection Upon the Case of Keziah Lewis

A REFLECTION UPON THE CASE OF KEZIAH LEWIS

By Master Rhys Taylor

The County Court of Pontypridd

I recently came into possession of a newspaper report of a court case in 1934. It concerns a Keziah Lewis. Keziah was my great-great-grandmother.

The newspaper report is from the Welsh newspaper of record, the Western Mail. It was dated 28 March 1934. Keziah was defending an action brought by her second husband, William Lewis (her first husband, a stonemason, having pre-deceased her), for the transfer of her properties over to him and the delivery of money invested by her in war loans and various banks. The case proceeded in the Bridgend County Court. It was heard by His Honour Judge Rowland Rowlands.

I am not only interested in this from a personal family history point of view but also because I am a barrister who practises in the field of family law. It has touched me. I am a member of the Wales and Chester Circuit and have spent many years plying my trade in the courts of south Wales, including, prior to its closure, the Bridgend County Court. The reporting of the proceedings is also of note, given that family proceedings in the modern age have largely been heard in private. The debate about privacy verses transparency is extremely important and goes to the heart of justice being seen to be done. Well-intentioned privacy concerns have often been the handmaiden for the jibe of there being a ‘secret’ family court. Not so in 1934, when a local newspaper reporter was available to be present in a small court centre in south Wales to take a note of proceedings and record it for posterity.

Keziah was the daughter of Catherine Lewis. Although unmarried and the mother of five illegitimate children, Catherine was canny and became prosperous. Catherine had started life as a furniture polisher but is noted in later census records as being the proprietor of a furniture store. Keziah’s capital was most probably derived from inheritance via Catherine.

The claim was brought against Keziah whilst she and Mr William Lewis were still married, as she refused to allow her capital to vest with her new husband. Family legend has it that Mr Lewis was known in the wider family as ‘Fiend’. These facts do not speak of a happy marriage.

The action was most probably brought under the Married Women’s Property Act 1882, to determine ownership.

The claim was for about £1500 and concerned four properties in Maesteg, numbers 1, 1a and 54 St Michael’s Road, Maesteg, and 1 Station Hill, Maesteg. His Honour stayed the proceedings, having suggested a settlement in the sum of £310 in full satisfaction of the claim, with each party to bear their own costs. It is hard to put a precise current value on the size of the claim or the settlement, but by the standards of the day and the geography, this was a lot of money. The size of the settlement by reference to the size of the claim, and the fact no order for costs was made, suggests a degree of success on Keziah’s part.

I am intrigued to read of the cross-examination of Mr Lewis in the news report, which remains frustratingly silent as to the identity of counsel involved. My first chambers, itself now consigned to history, was 33 Park Place in Cardiff. On the way into the clerks’ room, it had an ancient name board of barristers going back to about this time. Might the mystery counsel even have been one of them?

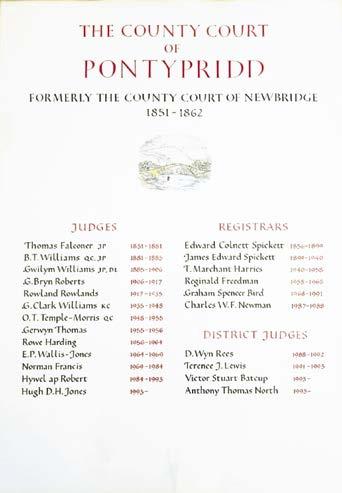

I can find little detail concerning Judge Rowland Rowlands. On a roll of honour, he is noted as being the judge in Pontypridd (a nearby court centre) from 1917 until 1935. A significant figure in his day, the Internet now yields only a shadow of him, as the father of Second Lieutenant Franklyn Theodore Rowland Rowlands, who was killed in the First World War. Keziah is buried, with her first husband, in the tiny Welsh hamlet of Llangynwyd. Legal actions about money and my abiding professional preoccupation are perhaps put into a different perspective when trudging around a churchyard looking at sunken and almost forgotten gravestones.

Years ago, by chance, I was intrigued to find, in a backroom of the Bridgend County Court, an ancient legal textbook summarising the common law. It was written by Master Tom Denning QC. It was dated from the 1930s – prior to Mr Denning’s appointment to the bench. Might this book even have been consulted when Keziah’s case was determined? I feel I can almost reach back across the chasm of time.

St Cynwyd’s parish church, Llangynwyd

© John Lord / St Cynwyd’s Church, Llangynwyd / CC BY-SA 2.0 Legal actions about money and my abiding professional preoccupation are perhaps put into a different perspective when trudging around a churchyard looking at sunken and almost forgotten gravestones.

Whilst the newspaper article is transparent about some ancient dispute in a way that many current family law disputes are not, I am also conscious that in writing this I am revealing something of myself. I hail from the Rhondda Valley, near to Bridgend. Whilst I have long since left it behind, it birthed and formed me. In a distant way, it still holds me.

What would Catherine and Keziah have made of their barrister descendent? Had I been that nameless crossexamining counsel, would Keziah have applauded me? Had I appeared for ‘Fiend’, would she have despised me?

Rhys Taylor 30 Park Place

Western Mail, 28 March 1934