30 minute read

I, Star Starlina Johnson

loaf on the couch, watch a movie, and smoke a cigarette. Wren can’t count all the parties he missed, the birthdays he forgot, the dates he stood up just because he was too tired to make an effort. He thinks about Tony living in that big house by himself. He thinks about how little he knows about his neighbor. He definitely has money, but what else? He glances at Bia’s garden. Okay, fine. Fine. He will not let them down, not today of all days. He gets up from his picnic chair and walks across the grass, up the steps of the porch, and knocks on the door of the yellow house. Tony has removed the hideous fake goose sitting next to the entrance and, in its place, has put an abstract statue resembling a dog. Woof. Wren shifts his focus, gapes at the green door. He admires the paint chips, the dent at the upper right-hand corner, the bronze ornate knob. He is charmed. Art. This is art. He giggles. The door creaks open, and a tall man in his sixties with a rough and gray beard, a long ponytail, and a flannel shirt steps out. Wren continues giggling. Tony gives him a stern look. Wren tenses up and immediately stops. “I’m sorry,” he blurts out. “What?” “Sorry. I mean, I like your door.” “Thanks, Wren. What do you want?” Wren relaxes when Tony says his name. Five years flash before his eyes: five years of Tony giving him shit about leaving stuff out on the lawn, Tony calling the cops whenever they threw a party on a weeknight, Tony initiating long and aimless conversations in the driveway that should have been a simple hello. They really have been through it together. Wren gets a little sad thinking about the fact he may never see him again. “Hey, man. We’re having a barbecue later. It might go late, some people are swinging by. You know I leave tomorrow? You’re welcome to join us!” Tony squints his eyes for a second. “It’s Friday, you’re good,” he says. “Where you going anyway?” “Florida.” “Florida? OK, well good luck with that.” “I dig the new—” Tony closes the door on Wren’s face before he can comment on

his redecorated patio. Damn, he was kind of hoping for one last pointless conversation with his neighbor. He shrugs. That went well enough. Tony: check. Wren makes his way back through the yard and to the side door leading to the kitchen, where he takes a seat on one of the two chairs in the corner. He stares at the checkerboard floor and the muck his four roommates have left the last few months. He lifts his head toward the cozy living room. He takes in the dark green walls, the refurbished wooden floors, the red patterned rug, the comfy sofas, the delicate string lights hanging from the ceiling—a spitting image of his Tumblr blog back in the day. He had always wanted to live in an old home, something historical, in the middle of a city, with culture and nature and great weather and a scenic view and awesome roommates. All Coconut Creek can give him is strip malls, wide interstate highways, cookie-cutter suburban homes, hot weather, and palm trees. Lots and lots of palm trees. He left that place—his hometown—as soon as he graduated college and moved to Burlington. Friends have come and gone, but this place was consistent. Now it’s his turn. The squeak and the pop of the staircase catch his attention. Ellie, the summer subletter, makes her way downstairs and faces him. She’s wearing beach clothes. “Hey, buddy,” she says, walking over and sitting down crisscross on the adjacent chair. Wren has never known such a beautiful human being. I love you so much. “Hey, Ellie, whatcha up to?” She strokes her thick, long brown hair and starts putting it in a ponytail. “Not much, going for a swim soon.” Wren thinks about going for a swim with Ellie. You wonderful mermaid. The one that got away. How I’ll miss you, my Vermont queen. She looks at Wren intently, waiting for him to say something, but he is lost in her big dark eyes, her rounded nose, the small scar on her chin. He never realized how much of a perfect oval her head was. She notices his pupils and lets out a chuckle. Ellie pulls her phone out of her pocket and starts scrolling through it. “Are you coming to the barbecue tonight?” Wren finally says. “I’m not sure. I may have a date.” Wren is way more disappointed than he should be, he has

Advertisement

only known this woman for two months. Why must the world be so cruel? “But I’ll see you tomorrow morning before your flight maybe!” she adds. The two sit in silence for a moment. Maybe I should ask her to get lunch. Paninis, maybe? Yeah, everyone likes paninis, good idea. Before Wren can say a word, Ellie gets up, grabs her bag from the mudroom, and opens the backdoor. “Bye, bud!” Wren doesn’t even get to respond when the back door slams shut. He sighs, slouches, then waits, hoping someone else comes down to chat. After a half-hour alone, he gets up, grabs the mop from the nearby closet, and cleans the disgusting tiles. Floors: check.

... Five o’clock passes and the only people at the house are Bia, who helped set the tables, and Eric, who is in charge of cooking the chicken. Wren is in good spirits, feeling extra chatty. After going around the house earlier and giving each roommate a separate gift, he believes that he has left his mark in each one’s life. To Bia, he had given his special pots; he knew that she would use them. It made him happy that he could contribute to her garden in some small way. To Eric, he had given his acoustic guitar, because Eric is a much better player than he is and would make great music with it. Before Bale left for improv, Wren was able to give him his small comic book collection, and before Ellie left for her date, Wren gave her his pots and pans, his window unit, some records from his collection (the romantic ones), a half-filled bottle of Glenmorangie, and three mangos. “Wow, dude, thank you?” Wren sweetly recalls leaving the lips of his lost love. Six o’clock. Wren’s comedown begins, and he can tell Bia and Eric are checking their phones more, a nervous look on their faces. He goes back to his picnic chair with a mason jar of water in hand. Wren gets a text from Charlie telling him he got caught up at work; he won’t be able to come tonight. “No prob dude. Will miss you,” Wren replies. Damn. I’m gonna miss that guy. He sips his cool drink and observes his roommates from a distance. Bia waters her plants and chats with Eric, who starts prepping the grill a few yards away from her. The glow of the afternoon sun is dreamy, and,

for a second, Wren feels like he’s traveled forward in time, that he’s inside a movie, witnessing the sweet moments of life unfold between two middle-aged partners. Eric listens contently as Bia tells him about her day. He shakes his head as she complains about her boss, cracks a joke that makes her laugh. In this moment, Wren hopes that Eric eventually tells her how he feels. Wren chokes up, goosebumps on his neck, suddenly aware of the fact he is alone. Where is everybody? “Big crowd.” He snaps out of his trance as Tony approaches and sits down on a wooden bench next to him. Wren doesn’t know which is more embarrassing: crying in front of Tony, or nobody showing up to his going away party. Tony lets out an awkward chuckle. “It’s still early.” “Thanks, Tony,” Wren says. He feels his mood sinking. “I’m surprised you came.” Tony shrugs. “Free food.” Eric waves from the grill. Tony continues, “Good trip?” “At first.” “Sorry to hear that,” Tony says. “Your door shit made me laugh, though.” Wren smiles as he recalls his thoughts from earlier in the day. He chuckles. Sips from his cup. “So why are you moving?” “Job.” “Couldn’t get one here?” “Not one in my field. I’m tired of waiting tables; I have a degree.” Up until this moment, Wren has done everything to not think about working that job. Government. Yuck. Somehow his application made it through the five-month administrative filter, and his hospitality degree is finally going to pay off when he works in the Parks and Recreation Department of a place where “park” means plain grass field surrounded by parking lots. “Change will be good,” Tony offers some of his wisdom. Wren is beginning to think the same, with each passing moment drawing none of the people he thought would come.

Eric walks over and hands Tony a plate with chicken and rice; Wren doesn’t feel like eating. Bia joins them, and the group makes light conversation. Tony laments about his goose, which the mailman had kicked, while the friends nod politely; Wren is silent as they discuss Tony’s new sculpture. The group talks about the weather—the most gorgeous day of the year, they all agree—the perfect time for a swim at the beach. The conversation continues, and Wren wants to run away, detaching himself like he’s always done. The group laughs as Eric tells a joke. Wren suffocates in their energy. Bia talks about the flowers, how all the plants are thriving this year. Tony compliments her dedication. He appreciates the wonderful scent every day he comes home. Wren can’t take it anymore. He is miserable. He stands up. He needs to go. Wren starts walking, the thick sweat on the bottom of his feet adding weight to every step. He just needs to get inside. His friends call to him, but their muffled voices jumble in his head. He ignores them and keeps walking toward the house, only ten yards away now. But his socks are a soggy sponge, his shriveled toes bring an unbearable discomfort to him, and he stops. He lifts his right foot, and, balancing on one leg, he pulls off the shoe and throws it across the yard. He switches legs and tries to do the same, but, when he pulls the shoe this time, he loses his equilibrium and falls on his ass. Unmoved, Wren wastes no time and frantically reaches for his socks, yanking them from his feet and chucking them ahead. He exhales deeply as fresh air wraps around both bridges, tingling. He brings his knees to his chest and leans forward, gently pressing his feet to the lawn. Ah. Temporary relief. The soft New England grass brushes lightly on the arches of his feet, and he is reminded of another reason he left Florida so long ago. In Florida, the grass is thick, it slices your skin. The New England grass tickles you like a feather. Florida grass is forever. It takes you for granted. New England grass knows it has six months to leave an impression, and it never lets you down. Wren sits there, rubbing his feet while his confused friends look at him, then at each other. This feels so nice. It’s seven o’clock now. For a moment, Wren stares at his wrinkled toes sluggishly coming back to life, then he gazes at the long roots of the oak tree bulging from the ground in front of him. He follows them with his eyes, up the

thick trunk, and to the tall branches and leaves dangling above him. One hundred years. This house has hosted three families, forty-two tenants, twenty-six parties, one fire, two renovations, and now Wren, all memories of days gone by. But the tree lingers, anchored to the earth, while Wren floats on. He thinks about how, earlier, he had asked the tree for wisdom. He hears it speaking now, but he’s not ready to listen. Bia walks up and sits next to him. “Hey.” “This sucks,” Wren mutters. “Yeah, it really does,” she says. “They’re all flakes. We’re here.” Wren turns around to Eric and Tony who have started arguing over where one property ends and the other begins. Tony has gotten up from the bench and is on the ground, trying to show Eric how the grass on his property is shorter. Eric points to a patch of weeds to remind Tony how he doesn’t use pesticides, how this must be his. Tony passionately tells Eric he will grab his deed from the safe in his shed. Bia shakes her head and begins to laugh. Wren begins to laugh with her. The hardest laugh he’s had in a long time. The two hold each other in their hysteria, which ends the property dispute between Eric and Tony. The two men look at each other, unsure what could be so damn hilarious. “Wanna go for a dip?” Bia asks Wren after they finish. He nods. One more sunset. The two help each other up. Tony walks up to Wren, gives him a firm handshake, and wishes him good luck before retreating to his yellow house. The group of friends clean up the remnants of the party that never happened. Tables and chairs get arranged neatly against the wall, leftovers get packed into glass Tupperware. Eric does the dishes, Wren dries them, Bia packs a beach bag. They throw all the leftover beers into the mini cooler and grab their towels. Before they leave the house, Wren changes the message on the fridge door: GHOST PARTY. BIG LOVE. ... They make it before the sun is down. Bia sets up a towel next to a big rock. Eric dives in the water like a fish. Wren walks up to the edge of the lake. The current creeps its way to the shore where he stands, and a cold rush bursts through his body, an electric force from his heel to his upper spine. It catches him off guard,

he tears up. A young couple swims away from Dog Beach, each lover touching the buoy a half-mile out before racing back to the shallows. A Labrador cannonballs into the water. Across the lake, the Adirondacks sit gracefully in their dark green coat. Sailboats slowly retreat to the bay. The wind blows on Wren’s face, and he is captivated, as if this were his first time seeing the familiar landscape. Bia watches him gaze at the view, smiles as she pulls a lighter from the bag. Eric obliviously flaps in the lagoon. Wren wipes his eyes as he turns around to face the rock. He takes a deep breath. Bia waves at him, then blows a kiss across the sand. He walks over and sits next to his friend. She hands him her joint; he takes a hit like it’s his last. Wren observes the waves crashing before him, back and forth, back and forth, then his eyes drift toward the sky. The sun starts setting and the fireflies come out, incandescent spots of light pulsing midair, but Wren is fixated on the fading horizon. He doesn’t notice Eric exiting the water, Bia temporarily disappearing, the two returning with creemees on a sugar cone. They eat their treat and laugh around him. Wren silently considers the sun lowering in the sky, the grass its rays nourish. He has always taken it for granted. Then comes an ambush, from both sides, Bia and Eric suddenly squeeze him in an unsolicited group hug. He finds comfort in the warmth of their bodies, the grains of sand pressing between their sticky skin and his. He stares at the mountains and promises to return eventually. His friends whisper something in his ear, but he is not listening. He closes his eyes and thinks about Florida, how it will be different. His two friends giggle together as they let go of Wren, get up, and start brushing the sand off their legs. Bia asks Wren to bring the towel when he’s ready, and she walks away with Eric to the entrance of the beach. Wren nods, but his eyes remain closed. In the darkness, he finds comfort in the slow hum of the waves ahead. In Florida, the current will be harder, the beach will be warmer, the sand softer. In the distance, the last sailboat is consumed by the twilight, the mountains are reduced to a silhouette. Another cool wind hits his face as Wren sits there alone, unable to see it all disappear.

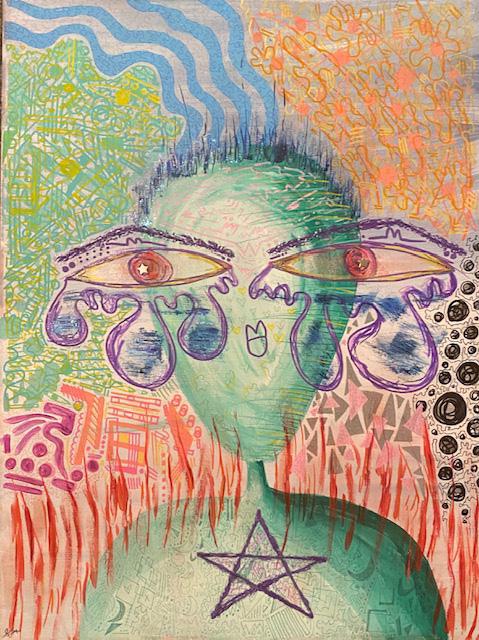

I, Star

Starlena James

Acrylic paint, paint pen, ink, hot glue on canvas

Human!

Salazar Cevallos

Oh my diggidy-dog bow-wow wow! If much sucking my belly in like SuperPerson, why I right fit through this puppy door, Mister Mailman! And barking hell, Mister Mailman, your patched-up crotch smells an awful lot like my wife. No I don’t bite.

Please pet me, Mister-Mustached-and-Moaning Mailman, please rub my navel and mutter goodie-boy re-affirmingly until I cry. Then I’ll let go of your pant leg I swear I’m up-to-date on my shots and pills and rabies because I’m a goodie-boy now no sudden moves I don’t mean to be so ruff!

Dog bless you, Mister-Moody-Mailman, your bones sure are tough, rubbery things to bury. But I was a goodie-goodboy I never bit, did I, Mister-blue-in-theFace-get-your-hands-off-my-neckMailman! Why’d you use the whistle, silly kitty, don’t you know I’m no-

Master! It’s you. You’re finally here. I missed you, Master. Stuck here for all these years! Waiting for you to open the door! Thirsty and hungry and poor. Hurry now, Master, unzip my skin and yank the fur off my pores and see me, Master, as the one you left behind.

Here in the house, stuck on this page, howling my heart out without paws or delay.

The Board Exam

Michelle Chadwell

She stood on her feet nine hours a day as a Dollar General cashier for less than eight dollars an hour. Her black rubber shoes did little to ease the pain that spiked through the soles of her feet. When she arrived home—a single bedroom she had rented out from a distant relative—she sat on her twin bed and opened the NCLEX-RN review book that she had purchased the week before. It cost more than an entire day’s wage. Her brows furrowed in concentration as she opened up to a bookmarked page, her frown lines deepening as she read through the dense material typed in what seemed to be the smallest font size. She had dreams when she emigrated to America. The land of the free, home of the brave. She was in pursuit of the great American Dream that drove others like her to flock to this nation. It was now 2009, over a year since she had arrived, and she had realized that the American Dream may be a trivial pursuit. Her nursing degree was not accepted here. She never understood it. Was the biology of the human body suddenly different when she stepped foot in America? She was told she needed to retake the nursing board exam, known as The National Council Licensure Examination, or NCLEX, designed to test the competency of nursing school graduates. A test notoriously difficult and unfriendly to immigrants. Never mind the fact that she was a nursing school graduate, had already taken the Philippine Nurse Licensure Exam, had passed with flying colors, and had already worked as a nurse in Manila. Despite this, she was determined to work hard to provide for her children half a world away, and still study to take the exam. She never had the chance to take it. She decided to emigrate to America after the sudden death of her husband, an American with whom she had had two children in the Philippines. He passed away after a low-risk appendectomy. After his

death, she struggled to provide for her two kids, one merely an infant who had been born only a month after her husband’s funeral. In the photos from that day, she stands with a bulging belly, clutching the hand of a little girl with pigtails, eyes wide and confused, unaware that her father would never be home again. Still, no matter how determined she was to take the exam, the demands of motherhood and of living in this country with less than a thousand dollars to her name proved too great. It wasn’t that she was incapable of passing the test, the truth was that she had been seduced into believing that the life she sought for her and her children was in America. She was seduced by the white picket fences she walked past. Seduced by the mothers walking along their affluent neighborhoods with their babies swaddled in Gap Kids attire in strollers that cost more than what she made in a week. Seduced by the notion that her daughters would grow up with much more than she had. Soon, she was not only working during the day at the Dollar General, but throughout the night, as a caregiver. She slept in between shifts, ate frozen dinners that she heated up in the small microwave on her desk, and still found the time to call her two daughters across the globe. Her daughters had no idea of her struggles, how she had to work until her feet went numb from the pain and her eyelids were as heavy as lead, or how she had to forgo meals and work with a grumbling belly. Her daughters only knew that their mother was working hard so they could one day live in America with her. They thought the world of their mother, never resenting her for leaving. They treasured the presents and treats that came in the care packages she sent every couple of months. They treasured the laggy Skype calls they shared when the Wi-Fi was strong enough. They had no idea of the ache and longing that settled in their mother’s bones. It was an ache that she felt with no end. An ache that she felt when

she waited at the bus stops with other immigrants, while they watched affluent white citizens drive in their Mercedes and BMWs with a cup of Dunkin Donuts coffee in their hands, while she sat with the bitter .50 cent coffee from the bodega down the street. She closed her NCLEX review book, not wanting to fall asleep with it left open on her lap as she sometimes did. Her back always ached when she fell asleep this way. Well, it ached more than usual.

Just a little longer, she constantly told herself. Just a little longer until she could save up enough money to have the time to study for the exam. Just a little longer until she could sleep. Just a little longer until she could hold her daughters once more, to hear their laughs fill a room, not echo from the tinny speakers of an old desktop computer she shared with her housemate.

Just a little longer.

How to Be a Woman in STEM

Kiersten Kiara Wright

Scientifically prove to them time and time (relative) again That like it’s okay to say like in like every sentence because like Evolution taught you that is how one survives a male speciMen’s interruptions. Generously grease the cog in your cognition

So Big Glen cannot swindle you out of the cash to pay for his lotto quick picks This time (absolute). Locate the nearest block button on every social media site to Escape self-proclaimed sugar daddies in your DMs. Hey, pretty baby, consider Motherhood and wifehood were words derived from different times and you

Seem like the kinda girl that wants to glaze herself in SPF-50 and lustrate in Tahiti’s solar-powered tides and live. Take the sun down if you want for its Evening maintenance and launder the earth if you feel like it, but maybe reMember that sometimes it is fine to leave the leftover dew for someone else to

Sop up the next morning, or the day-bloomers folded a little while longer. Turn one hundred eighty degrees. Then never apologize for changing your mind Even when the odds are against you and fallout is probable. Be like Big Glen More often. Occupy your space in the third dimension. Accept time too. Age

So they know the ‘90s dolphin tattooed on your lower lumbar still looks H-OT! despite the fact that your skin is more crimped than your hair used to be. Eat the raw batter you know might be soaked in salmonella if it means you can Move on afterward. Hold tumbled carnelian and rose quartz in your way-too-

Small pocket if sometimes you simply want to feel like a good witch instead of The woman in STEM. Do not record your failed experiments unless you Etch them onto the B-side of the moon. And always mimic that same Moon’s unwillingness to have its fullness captured by just any photograph.

Modern Day Cowboy

poem Charlie Wyckoff

With eyes sharp like boot spurs and sneakers caked in clay, the Modern Day Cowboy drives off into the blinding sunset.

He shimmers, like an Adonis in Levi’s, like heat mirages on blacktop parking lots, like fireflies when yesterday there were only mosquitos.

When golden hour rears its horns he’ll be the first to smile at the death of the day. Even though he knows tomorrow will be overcast, another line-cook shift of hazy monotony

Just give him a clear night sky, pinpricks in God’s embroidery spotting up his tired vision. Give him that and that alone.

The quiet understanding of a life he never got to live will come to him vivid in a cloud of gun smoke and dust kicked up by the heroes of his dreams.

illustration Cass Yao

digital illustration

I went to Utah

I’d be lying if I said I don’t think about it anymore The night She drove me home and held me while tears wore me down;

my razor blades and their magnetic pull, how it would’ve been so easy. I’d be lying if I said I never think about my mother finding me the next morning in the bathroom she just renovated

But I think more about you, after one more rotation around the sun. you, at home with your mother having the same thoughts as me. I think about the next morning, how I was still here, and you weren’t.

I think about your mid-length curls, more structured than mine; shared friends, 2011 CRVs, and planning road trips with our girlfriends, our shared city, shared campus

I stare at the oak trees here and wonder if you loved how the sun shines through hanging moss in the evening, how the world turns yellow at sunset, how perfect it feels in the first week of February

Shannon Driscoll

Sometimes, I think about an alternate reality where you stayed, and I left. where you second-guess your grief; worry too much that you care too much about me.

Do you think about my mom, like I think of yours? holding on to pictures of over-sized t-shirts on little bodies, and knotted beach curls. All the indications of a perfect summer vacation, of a perfect, happy child Maybe you drive to Utah; pack everything in your CRV, with windows down, and wind whipping through your hair Maybe you glance to your side as She snaps a picture of you with your most genuine smile. Perhaps you find yourself awake the next morning with air in your lungs, and later you find yourself driving past my old apartment on Tennessee St Maybe you find yourself asking; “why me? why me and not you?” Because I went to Utah; drove cross country in my CRV, turned 22, graduated college, I woke up the next morning. I’d be lying if I said I never ask why; “why me and not you?” --S.D.

The Kudzu Review

Nonfiction

How To Measure a c Memory

Claudia Abdelhaq

Al Jubeiha

My cousin, as old as me, half my height and width, could be blown away if left unsupervised. They live on a mountain in Al

Jubeiha where the winds are so loud and pushy, they’ll get in your eyes and force a few tears. Mama breathes it in and out, ya Allah we don’t have air like this fil Rabieh, she says. My three siblings and I walk into their little home, an already big party of five boys, their sheikh father, and his dying mother. Our khalto is cooking dinner, ma’loobeh probably, we could smell the fried eggplant from out the door; she knows how much we love it.

She yells my name from the kitchen and tells me to come, t3ali.

I walk in and she’s holding her hands up, a bommali the size of a small soccer ball sitting in each. I smile so big when I see she has bought more since the last time I came. I had never had it before then and, while my siblings thought it to be too bitter, I couldn’t stop eating it. She walked in to set the table only to find me seated with bommali juice running down my arms, pulp in my teeth, and the peelings in a tall pile. She couldn’t stop laughing, she yelled for mama who’s sitting on the porch, t3ali shufi bintik, come look at your daughter! She holds the bommali now, two weeks later, in hands that look like my mother’s and says, for you.

Gabby is my friend. She didn’t laugh when I accidentally said half of my sentence in Arabic, instead she gasped and said, oh my god, say more! Sayyyyy hello how are you today. Or when I told her I wished my hair was gold like hers, she’d brush her fingers through mine. But look at yours it’s so dark and pretty. Let’s switch. Can I braid it? She’d ask how it was in Jordan and what my home looked

Gabby

like, who my friends were and what they were like, why I left and why I came back. At lunch, when kids tell me my mother’s grape leaves look like poop, she gives them a face and says, that’s rude, can I try? And when she does, her eyes widen so big you could swim in the blue, mmmm! How does she make it?

I don’t know but it takes her two days. Sometimes I help with the rolling. Want another?

I do, she’s laughing, two days? Is that a joke?

No, I’m serious.

She studies the grape leaf, unrolling it a bit before fitting it into her mouth in one big bite. She’s so kind to me. I tell her this one day and she’s laughing through her nose, well...yeah why would I not be?

This house doesn’t really change much. My cousins’ sheikh father’s beard is longer, it catches on shoulders and shirt buttons. They say it’s where he holds all his religion. They say if he trimmed it, he wouldn’t be so cranky, but it keeps him warm in the winter. All the kids go out to play in the sloped alley. I sit on the stairs, my older cousins on the inch-wide rail, seven feet above the concrete ground. They sit so comfortably there, swinging their legs, talking, and teasing each other like they aren’t one wrong move away from death. I feel on edge, like I’m the one sitting there. Mama always told me how so many kids die this way, falling over a balcony, diving into a pool, or falling into a well, just one wrong move. But I don’t say anything, their mom probably tells them the same. Claudia, do you still hate me, the oldest of the five asks. It wouldn’t be a visit if he didn’t. Yes, now go away.

Khalto brings out the chickpeas, the still-green, fuzzy chickpeas still on their stems, never given the chance to grow more because they’re so tasty that way. Here, she splits the bunch between us, until dinner’s ready. We pluck the peas one by one, pop them in our mouths, and toss the rest over the rail. When we’re finished, we look down at the pile of pea pods and cigarette butts and watch the stray cats investigate for something more. If we look to the right, we sometimes see the next-door neighbor, Enas, standing on

My Cousins’ Sheikh Father’s Beard

her front steps. She’ll say a few words and go back inside. Sometimes when we don’t see her, we hear her, crying and shouting words we can’t make out. We head back inside.

We eat dinner and sit around till midnight. I’ll pick on my puny cousin ‘cause I’m bored. They’ll smoke hookah in the back and laugh so loud the whole block can hear. Ya Allah, something about chai and argeeleh, mama says, something about this air, and something about this mint fil chai. When it’s time to go, we put on our coats. Khalto stops us at the door with a cup of ice-cold water, every one of you has to take three sips. But I’m not thirsty. Fine then just one. Why? So you can be as cold on the inside as you are on the outside. She holds it to my mouth, tipping it until I’m on my third, yallah yallah so you don’t get sick.

Paranoia is a little girl.

She covers her mouth while she yawns, says A’oodhu Billahi min al-Shaytan ir-rajeem so the evil spirits won’t sneak in. She recites Surat Al-Ahad five times in case she miscounted and did it twice instead of three and once more in case one wasn’t recited perfectly. She lays awake at night with her eyelids closed, her nose an inch from the wall beside her, her fingers running the hills of rushed, ridged paint streaks. She listens to the tree scratch her window, to the owl hoot her goodnight anthem. Her mother walks in to kiss her goodnight. Bit 3yti, why are you crying? She asks, what if you and daddy die? Though they are perfectly healthy. Her mother holds her still and tight, say mgher shar, Paranoia! And so she lays. Mgher shar, she repeats, hand on the hills till she drifts to sleep.

Paranoia is little and lonely and loud.

She walks on her tiptoes in the day. On the left side of the stairs, because the right is squeaky. Her hands hold each other and hide behind her back so no one can see. She doesn’t let her bones rest at night. She starts talking to herself quietly. Her teachers ask where her mind went, Paranoia, are you still with me?

Soon she found company. A connection so light and tender. So special in the way they would hear people speak of their soulmates and think, no way they really know, they think they know! But they don’t, and laugh in their tiny pink room where the wooden floors creaked a melody.

Say Wallah

She’d cry if Paranoia slept with the covers over her head; she could run out of breath and suffocate to death. She’d check mom’s breathing in the night; the grief could catch her in her sleep. She wouldn’t whistle in the dark or sing at dinner; the shayateen might sit and eat. She’d ask God for forgiveness if she forgot to say A’oodhu Billahi min al-Shaytan ir-rajeem when she yawned. She’d say, no way, in disbelief when Paranoia listened to all these little things and said, these are mine too.

Say Wallah.

Wallah. These are mine too.

She’d swallow mistreatment some days. On others, she’d return it with a clever smile, one that could anger the shaytan himself. But let days of ungiving silence pass and watch how they drowned her in sadness. She tells Paranoia of her plans to break it today, the silence. Paranoia asks why, and her face fills with worry, what if they die?