7 minute read

We Are All Shut-ins (for) Now

BY KEVIN ARMBRUST

“E very situation is different, but we know the end.

Advertisement

We know that we are going to heaven because of Jesus. ...

Keep that compass pointed to

Jesus Christ alone as Savior ... it is peaceful and true,” said the Rev. John Zimmerman, pastor of Immanuel Lutheran

Church, Scranton, Pa., and

St. John’s Lutheran Church,

Pittston, Pa. As one of his members told him, “I follow the one who rose from the dead. I go where He goes.”

Scranton, Pa., the setting for “The Office,” sits in the northeastern hills of the Commonwealth of

Pennsylvania. This blue-collar community contains divergent ethnic (largely European) neighborhoods situated on the surrounding hills. It is in this setting that Zimmerman serves as undershepherd of the Good Shepherd. He proclaims the Word and administers the Sacraments. He visits his people. As all pastors, he goes to those who are shut in, those in nursing homes, those in the hospital. He calls on those who are not attending worship.

Zimmerman has been a pastor for four years, since graduating from Concordia Theological Seminary, Fort Wayne, in 2016. He spent much of those first years establishing a normal routine — for himself and for those in the congregations he serves. Zimmerman has worked to get to know the members of these parishes, and they trust that he will provide Word and Sacrament ministry for them.

From Boom to Bust

Anthracite coal — black coal — was once the premier fuel for heating houses. Although difficult to ignite, anthracite burns easily once lit and provides a low-ash, clean and low-smoke fuel. From the early 1800s through World War I, anthracite grew in popularity and was often the

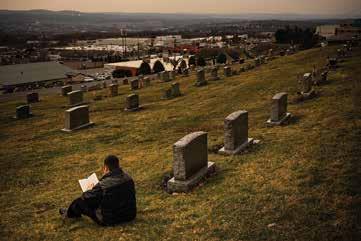

The Rev. John Zimmerman, pastor of Immanuel Lutheran Church, Scranton, Pa., and St. John’s Lutheran Church, Pittston, Pa., takes a moment to read a devotion as he visits Immanuel’s cemetery. fuel of the elite. The mines of the Northern Field of the anthracite mining region of Northeastern Pennsylvania (NEPA) employed many of Scranton’s citizens.

All that came to a screeching halt on Jan. 22, 1959. In the Knox Mine, workers punctured a hole from the mine into the Susquehanna River above the mine. The resultant flood killed 12 miners and took three days to fix. This devastated the surrounding area and the coal-mining industry, as natural gas and other fuels were simultaneously gaining in popularity. Church attendance plummeted with the loss of the socioeconomic bedrock of the town. Yet, the communities of NEPA continue on.

At the time of the accident, Immanuel averaged between 300 and 400 people each Sunday. The congregation offered services in German, Polish and English. As mines and businesses shut down, the church, which began in 1895,

Zimmerman distributes the Sacrament to Immanuel member Olga Kropa during a visitation on March 10.

lost many of her members. Yet the congregation continued, and most of the families there today are related to founding members.

Like each parish and community, Immanuel and St. John’s present challenges and opportunities. Part of the challenge of NEPA is the proximity to large cities. Scranton is about two hours from both New York City and Philadelphia. Young professionals often move to the larger cities. That, combined with smaller family sizes, means the congregations are largely aging and facing different challenges. “Here at Immanuel, we try to meet [those] needs,” explained Zimmerman. “A small group cannot make Sunday service, so we have Wednesday night services.”

Recently, four previously unchurched people who started coming to the Wednesday night service were baptized.

“It’s daunting, yet the joy is that the Spirit is at work,” noted Zimmerman. “God says to preach the Word in season and out of season. So, I do.”

Zimmerman may be relatively new to the pastoral office, but he is not unfamiliar with the vocation. He was born while his father was on vicarage from Concordia Seminary, St. Louis. His grandfather was a pastor, as are his cousin and brother.

The Challenge of COVID-19

But his established routines and visits came to a screeching halt with the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Scranton, with the rest of the world, was shut down, with gatherings stopped and congregations no longer offering worship in person. “We are all shut-ins now,” said Zimmerman. “In the midst of the pandemic, we need the comfort of meeting together and receiving the Sacrament. ... It’s really hard to not be able to meet together.”

Like all pastors, Zimmerman seeks to serve His people in humble obedience to the Lord’s will. At the same time, he obeys the laws and regulations of the land. On March 19, Pennsylvania allowed religious institutions to continue to meet under certain restrictions, such as by maintaining social distancing and limiting gathering

Zimmerman teaches Bible study at Immanuel on March 10.

sizes, but an April 16 communication encouraged leaders to find alternatives, asking that people not gather at this time.

As a result, Zimmerman’s congregations have offered services with reduced attendance and social distancing, while stressing that members were not under compulsion to attend. His elders reasoned that if people are able to go to the grocery store to get bread, then people should be able to feed on the bread of life. About

Church member Alan Drummond listens during Bible study at Immanuel. half of his active members have been able to attend and were thankful for the opportunity. Others have been unable or unwilling to attend. For those, Zimmerman — like others in the Synod — has worked to provide online services and opportunities.

Zimmerman also has continued to visit — although the visits were on the phone instead of in person, and it was not possible to bring the Sacrament of the Altar. Yet, the ministry of the church continues. And sinners need to hear the Word of God.

The ministry of the Word still includes Law and Gospel proclamation. The people of God still need to hear that their sins are forgiven. Prayers may be said over the phone instead of in person. The necessitated distance means that touch is no longer an important part of the visits.

And in all of this, Zimmerman and his people have longed for the day when they can return to gathering together. “I hope the Body of Christ can admit that they missed meeting together,” said Zimmerman. He noted that it is vital that the church “hunger and thirst for the feast, for the Sacrament, for the forgiveness of their sins.”

A Time to Reflect

Similar to other difficulties faced in the history of Scranton, Pittston or other towns, this present situation causes the church to pause and adjust. Yet, the Word and the Sacraments remain the promises of God, and those called to proclaim and administer continue faithfully in that calling.

“I would like our congregation to look back and say, ‘Despite the fear of 2020 we met together with our Lord and Savior, through Word and Sacrament,’” said Zimmerman. “We said, ‘Alleluia! Christ is risen!’ We made sure that those who can’t come are still hearing the Word.”

And the people whom Zimmerman serves are blessed by that Word and their pastor’s efforts to provide podcasts of his sermons. “What a great idea to create the devotional in the church. The listener heard a powerful Easter sermon instead of a well-constructed and presented essay. ... Good stuff,” said Joan Jaditz, a member of Immanuel, Scranton. She continued, “Your messages are tremendously appreciated by us as they provide a familiar voice sharing the Word, and that instills comfort and peace.”

“I don’t have all the answers,” admitted Zimmerman. “It is good to have charity and patience with each other as we decide how best to go forward.”

Anthracite coal, demographic shifts and other factors continue to change the situation in NEPA, and the coronavirus has brought even more disruption and questions. Yet, pastors like Zimmerman continue to bring the Word and Sacraments to God’s people.

Kevin Armbrust is director of Editorial for LCMS Communications.