11 minute read

They Faced Death Without Flinching

Diane Atkinson recounts the story of the suffragettes’ fight for votes for women that is told through the banner designed by the Scottish artist Ann Macbeth.

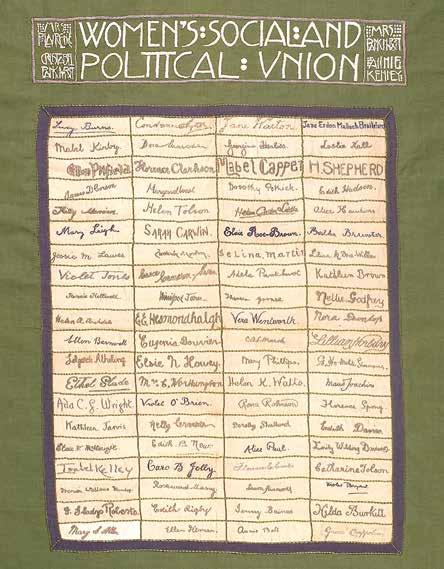

Ann Macbeth’s banner, which was originally designed as a friendship quilt, hangs in the suffragette display at the Museum of London. It is one of the most important artefacts of the militant campaign for the vote. The banner records the names of 80 women who had served prison sentences for various offences between 1908 and 1910, including obstructing the police, protesting outside the House of Commons, heckling at political meetings and smashing windows. Almost all of these women had been on hunger strike and ‘faced death without flinching’ , as the suffragette newspaper Votes for Women declared.

The quilt was donated to the Scottish Exhibition and Bazaar held by the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) at St Andrew’s Hall, Glasgow, in April 1910, by Macbeth. She was head of the Needlework Department of the Glasgow School of Art and a member of the Glasgow School art movement, along with Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Despite being blind in one eye after contracting scarlet fever as a child, she designed and made intricate appliqué and embroidery, painted ceramics with a favourite motif of blowsy tea-roses, and also taught metalwork and bookbinding at the art school. ‘Annie’ Macbeth was born in Bolton in 1875; her father was a mechanical engineer and her grandfather was the portrait painter Norman Macbeth RA. Macbeth was herself a militant member of the WSPU and was sent to prison, where she went on hunger strike in 1912. She was a semi-invalid for several months after her release, writing to a colleague: ‘I am still very much less vigorous than I anticipated … after a fortnight’s solitary imprisonment with forcible feedings.’

Above Ann Macbeth’s WSPU banner, 1910, Museum of London. Image © Museum of London. The banner is currently on display in the museum’s People’s City gallery.

Macbeth’s lettering for the title and upper panel of the quilt is pure ‘Glasgow Style’ . She has elongated the letters vertically, the horizontal lines of the lettering cap and underline neighbouring characters, the V-shaped U recalls Roman typography, and the decorative motif of dots around the names are reminiscent of Mackintosh’s designs. Macbeth made the linen quilt in the colours of the WSPU: purple for dignity, white for purity, and green representing hope. The names of two of the founders of the militant movement, Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel, along with two of the leading lights of the movement, the treasurer Mrs Emmeline Pethick- Lawrence, and the mill-girl Annie Kenney, flank the title of the ‘Women’s Social and Political Union’ which blazes across the top.

The main section of the quilt consists of 80 rectangular pieces of linen which are sewn together and bordered by green and purple panels. The pieces are embroidered with the signatures of women who had been to prison and gone on hunger strike for ‘the Cause’ in their struggle for the status of political prisoners. Many had been force-fed if they refused to eat, which involved being tied to a chair and held down by wardresses, while liquid food was poured by the prison doctor into a funnel and rubber tube which had been inserted into the nose or down the throat.

Pethick-Lawrence bought the quilt from the exhibition for ten pounds and had it made into a banner. It was first used in public on the Prison to Citizenship Procession, held in London in June 1910, and has been displayed on various significant occasions since then, including a Suffragette Fellowship tea party in Westminster in 1950, where Lady Astor was a guest of honour.

Emmeline Pankhurst

Christabel Pankhurst

Founded in Manchester in 1903 by the Pankhurst family and women from the Independent Labour Party, the WSPU joined the law-abiding, moderate women’s suffrage struggle that had started in the 1860s. Frustrated by the lack of progress made by Millicent Fawcett’s suffragists, the Pankhursts rejected their polite approach and campaigned using methods which earned them the nickname ‘suffragettes’ , a sneering term used by the Daily Mail in 1906 which they happily embraced. The WSPU’s direct style

of campaigning shook Edwardian society to its core. The insistence of the authorities that suffragettes were ‘common criminals’ and not political prisoners (which they clearly were), and the refusal to grant the privileges gained in the nineteenth century by male political campaigners who had been incarcerated, led to a life-and-death struggle between WSPU members and the prison governors. From 1909 there were hunger strikes, and forcefeeding was inflicted on the women in prisons throughout the UK.

Annie Kenney

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence

Marching across the banner in four columns are the names of some of the leading figures and foot-soldiers of the militant campaign. Lady Constance Lytton, whose father, Earl Lytton, had been Viceroy of India, provided two signatures, her own and that of her alter ego, ‘Jane Warton’ . Warton was a working-class woman whose identity Lytton created to get herself arrested while protesting outside Walton Prison in 1910. She wished to experience the same treatment meted out to working-class suffragettes who went on hunger strike and were force-fed; she had earlier been spared this because of her title. Rosamund Massy had the support of her mother, Lady Knyvett, also an active suffragette, and her own husband, who was a colonel in the Dragoon Guards.

Many were well-educated women who engaged with the community in social work. Jane Brailsford, married to the well-known Liberal journalist Henry Brailsford, had studied Greek at the University of Glasgow. Ada C.G. Wright, who was photographed in 1910 by the Daily Mirror sprawled face down on the pavement after being attacked by a policeman, ran a club for workingclass girls in Soho. Dorothy Pethick, sister of Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, was the superintendent of a girls’ club.

The movement’s fast-growing workingclass membership is also in evidence on the banner. Jennie Baines, aged 42, the wife of a shoemaker, had worked in a gun factory when she was 11 years old; ‘Beth’ Hesmondhalgh, 27, was a cotton winder married to a railway signalman; and Catherine Worthington, 32, was the wife of a brass moulder; all 3 were from Preston. Ellen Pitfield, 30, was a midwife from Dorset; Selina Martin, 27, was a servant in Lancaster; and Theresa Garnett, 25, was a pupil-teacher from Leeds.

The embroidered signatures mostly represent women from England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales. Two, however, are American, Alice Paul, 24, and Lucy Burns, 33, who were studying in London and met at Cannon Row police station after being arrested at a protest in Parliament Square in 1909. They had active suffragette careers before returning to the United States, taking WSPU tactics with them to invigorate the campaigns in America where women were still unenfranchised.

Women from diverse backgrounds are here, too. Vera ‘Jack’ Holme, a male impersonator and the lover of the Hon. Evelina Haverfield, was for a time Mrs Pankhurst’s chauffeur and the leading horsewoman at suffragette processions. Florence Spong, one of five suffragette sisters, was a weaver, artistic dressmaker, woodcarver and lacemaker. Alice Hawkins of Leicester was a shoemaker and mother of six children.

There are women of all ages. Jessie Spinks, a Londoner, was 17 when she joined in 1907, changing her name to ‘Vera Wentworth’ to spare her shop-keeping father’s embarrassment. The oldest name on the banner is that of Ellen Pitman from Bristol, who was 52 years old in 1909. Nurse Pitman was by no means the oldest woman to support the militant cause. The distinguished feminist Elizabeth Wolstenholme Elmy, born in 1833, was 77 years old when she walked alongside Mrs Pankhurst in a deputation to Parliament in 1910.

Other notable figures include Marion Wallace Dunlop, the first suffragette to go on hunger strike. The actress Lelgarde Atheling signed, as did Kitty Marion, a music-hall performer, who was forcefed 232 times in 1913 alone. Helen and Catherine Tolson were suffragette sisters from Manchester. Mrs Pankhurst’s youngest daughter, Adela, whose wayward ways saw her dispatched to Australia in 1914, is there. Of the three nurses on the banner, Sarah Carwin, Ellen Pitman and Ellen Pitfield, the last’s copperplate autograph is the most poignant. A nurse and midwife, Pitfield died of cancer during the Votes for Women campaign. She was released from Holloway Prison hospital wing 45 days into her 6-month prison sentence, having been imprisoned for setting fire to a wastepaper basket and throwing a brick through the windows of a London post office in 1912. She died six months later.

On the left flank of these marching columns, schoolteachers Mary Leigh, 23, and Edith New, 31, were the first suffragette window-smashers, and were released from Holloway Prison in August 1908. They were incensed by the ‘violence and indecency inflicted on their comrades’ who were being led by Mrs Pankhurst and her deputation. The group had been trying to enter the House of Commons on the evening of 29 June 1908 to speak to Prime Minister Herbert Asquith to demand he grant votes for women ‘without delay’ . Leigh and New slipped away from the mêlée in Parliament Square and broke windows at 10 Downing Street; they were sentenced to two months with hard labour for wilful damage. When arrested, New declared to the constable: ‘Freedom for the Women of England. We are martyrs’ , and in court both women said they would do the same again. Leigh added that the next time it would be a bomb. Her suffragette career included roof-top protests and an attempt to burn down the Theatre Royal in Dublin. In 1908 Leigh left her job, became a paid organiser, served several prison sentences and was one of the first women to be force-fed in 1909. She was a political activist for the rest of her life.

Preston suffragette Edith Rigby joined the WSPU in 1904, and marches in the adjacent column beneath two of her working-class ‘sisters’ , Beth Hesmondhalgh and Catherine Worthington. These three women were arrested on 3 December 1909 while protesting outside the barricaded Preston Public Hall, where Winston Churchill, President of the Board of Trade, was due to speak for the People’s Budget. They were sentenced to a month in Preston prison where they went on hunger strike. Edith Rigby’s brother Arthur was incensed at her behaviour, and in court pointed at a suffragette who was wearing lipstick, and sporting a hat at a rakish angle: ‘It’s that painted Jezebel who has led my sister astray. ’ Edith was too strong a character to be ‘led astray’ . A doctor’s wife in her thirties, she was detested by her middleclass neighbours for leading the Preston suffragettes, and also for her refusal to behave the way expected of her class. She chose not to wear a corset, smoked in public and treated her servants as equals.

In the central right column is Mary Phillips, who in 1907 was photographed selling copies of Votes for Women, while several men look on, surprised at her ‘unwomanly behaviour’ of being a visible and audible presence on the street. She stood in the gutter to avoid being arrested for obstruction. Glasgow-born Phillips, who was 27 and a new recruit to the WSPU having for the previous 3 years been a suffragist, declared: ‘I didn’t enjoy anything until militancy began; when I was just a suffragist it was boring.’ Phillips was one of the 12 members of Mrs Pankhurst’s deputation who had marched to the House of Commons in 1908 to meet the Prime Minister. After he refused to see them, they walked to Caxton Hall. More suffragettes appeared in Parliament Square in hansom cabs, and on the top of horse-drawn omnibuses. Using megaphones, they urged the public to clear a path for the deputation’s second attempt to enter by the Strangers’ Entrance. The combination of a huge police presence, a growing crowd and many suffragettes trying to wriggle through the heavy police cordon led to the ‘fiercest of scrimmages’ . Phillips, who was one of the 27 women to be arrested, was sentenced to 3 months in prison for obstruction. She wrote: ‘I thought prison was rather a joke … you were undressed, weighed and measured and then given these awful clothes. ’

Edith Rigby

Emily Wilding Davison

In the far-right phalanx we see the autograph of Emily Wilding Davison. Born in 1871, she joined the WSPU in 1906 and 18 months later ‘came out’ as a suffragette, resigning her post as governess to the children of a Liberal MP and becoming a dedicated militant. By the time the quilt was made she had served four prison sentences, two in Holloway and two in Strangeways in Manchester. The first was for a month for trying to enter the House of Commons in March 1909; the second in July 1909 was for two months for protesting outside Lloyd George’s meeting in Limehouse; she was released after a five-day hunger strike. The third was served in Strangeways for obstruction outside a Liberal meeting in September 1909. Sentenced in October 1909 to a month’s hard labour at Strangeways, she went on hunger strike and was force-fed. Several more prison sentences later, on 4 June 1913 at the Derby, Emily tried to stop the King’s horse, Anmer, during the race. Her deathly dash was captured on film and made her the WSPU’s first martyr to the cause.

In 1926 the ‘Suffragette Club’ , formed to preserve the story of the militants’ struggle and the role of the Pankhurst family, began to collect and archive the artefacts of their campaign. In 1947 there was a Suffragette Museum at 41 Cromwell Road. In 1950 the Suffragette Fellowship, as it became known, donated thousands of items to the London Museum in Kensington Palace. In 1975 the museum merged with the Guildhall Museum to form the Museum of London, and moved to its current premises in the City in 1976. The banner appears to have arrived at the London Museum during the 1960s, but its provenance is something of a mystery.