9 minute read

Sheer Decadence

For the English Decadents of the 1890s, certain ‘golden books’ – from Huysmans’ A rebours to Wilde’s Salomé with its distinctive illustrations by Beardsley – played a central role in defining the movement, as Matthew Sturgis reveals.

‘It was the strangest book that he had ever read. It seemed to him that in exquisite raiment and to the delicate sound of flutes, the sins of the world were passing in dumb show before him. Things that he had dimly dreamed of were suddenly made real to him. Things of which he had never dreamed were gradually revealed. ’

In The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), Lord Henry Wotton presents the beautiful and impressionable Dorian with a slim yellow-backed French novel. This volume becomes Dorian’s guidebook – his Baedeker of Decadence – leading him down a path of ever-more refined pleasures and calculated excesses, towards destruction. The book is not given a title but, as many of Oscar Wilde’s readers would have known – and as Wilde himself later acknowledged – the work was J.K. Huysmans’ novel, A rebours. Published in France in 1884, with English-language editions only appearing from 1922 (translated as Against the Grain or Against Nature), it tells the tale of an effete aristocrat seeking escape from the tedium and crassness of the modern world, in acts of aesthetic selfindulgence and perversion. In the end he abandons even sex, for the more complex pleasures provided by rare perfumes, artificial plants, late Latin literature and a jewel-encrusted pet tortoise.

It was the book that, perhaps more than any other, distilled the essence of Decadence. Drawing on the novel ideas of Théophile Gautier and Charles Baudelaire, it rejected the nineteenth-century cult of material progress, and proclaimed instead a retreat into a realm of amoral aesthetic pleasure; a creed not merely of Art for Art’s Sake (a dangerous enough notion to most Victorians), but of Life for Art’s Sake. The artificial was to be ranked above the natural, the complex above the simple. The Dandy, the Bohemian and the Artist were to be the heroes of the new era. These were arresting new ideas, and they had a particular attraction in the artistic circles of 1890s London. They retain something of their force even now.

Lord Henry Wotton – brilliant, informed, inquiring – would surely have been a member of The London Library, and I did wonder whether the copy of A rebours that he lent to Dorian would perhaps have been borrowed from St James’s Square. (The proscription against lending books to third parties is exactly the sort of rule that, as an inveterate subversive, he would have been delighted to flaunt.) But it seems not. The title is not listed in the Library’s 1888 catalogue, and appears only in an 1897 edition in the 1903 catalogue.

The idea, however, that a particular book might act as the vade mecum to a new (and dangerously exciting) way of life was a pervasive one for the Decadent writers of the 1890s. The novels – and the histories – of the period are littered with such personalised sacred texts. And The London Library would have been able to supply most of them.

Wilde himself nominated as his ‘golden book’ Walter Pater’s 1873 volume, Studies in the History of the Renaissance. Although ostensibly a collection of essays about the artistic flowering of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, its celebrated ‘Conclusion’ prefigured A rebours. Drawing on some of the same ‘poisonous’ French sources that Huysmans used, it urged its readers – rather than following any higher moral purpose – to seek only the most intense and carefully discriminated experience of each passing moment, and for experience’s sake alone. The book was denounced from the pulpit as the gospel of a ‘New Hedonism’ . And, of course, that was what attracted Wilde to it. He claimed never to travel without a copy.

It was, he said, ‘the very flower of decadence: the last trumpet should have sounded when it was written’ . In truth, though, there were several other books that he might just as well have plucked as the ‘very flower of decadence’: Mademoiselle de Maupin (Gautier’s 1835 tale of a cross-dressing temptress, and another work that Wilde claimed not to be able to travel without); as well as Baudelaire’s Fleurs du Mal (1857) and Edgar Allan Poe’s Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque (2 vols., 1840), both of which Wilde regarded as essential reading.

The English Decadents of the fin de siècle defined themselves through the books they read and the books they owned. Obsessed as they were with surface, with the supremacy of form over content, it mattered to them not merely what the books said, but how they looked.

This was the great age of the ‘book beautiful’ , of the limited edition on handmade paper, the lavishly illustrated de luxe production, and the choice volume bound in coloured boards, gilt vellum or even human skin.

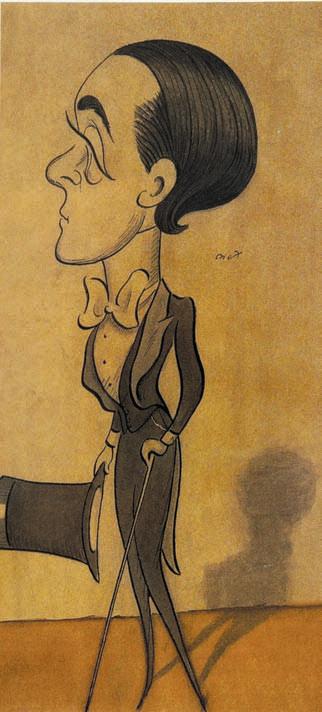

The man who embraced this notion most enthusiastically was John Lane, co-founder with Elkin Mathews of the Bodley Head publishing house. A brilliant publisher in his own right, he was fortunate to have in the service of his vision a bona fide artistic genius: Aubrey Beardsley. Beardsley’s arresting pen-drawn images of femmes fatales and ambiguous men became the very symbol of the age: they were entirely new, decidedly unhealthy and tinged with a pervasive aura of sex. (The attenuated unhealthiness of the images was, moreover, a just reflection of their creator: the dandified but consumptive Beardsley would die in 1898 at the age of 25.) For the public and the press it was Beardsley who gave Decadence its distinctive ‘look’ . And it was a vision fixed, almost invariably, to a book. Beardsley created the cruel ‘japonesque’ illustrations for Wilde’s Salomé (1891; English edition published in 1894), the elegant calligraphic design for Ernest Dowson’s Verses (1896), and the cover for M.P. Sheil’s wonderfully over-wrought decadent detective story, Prince Zaleski (1895).

He was also the art editor of and principal pictorial contributor to the Yellow Book, the radical periodical – launched by Lane in the spring of 1894 – that seemed to define the moment. The subversive intent of the publication was announced by the fact that – like A rebours and so many other dangerous French novels – it had a yellow cover, with the Beardsley image of a ‘leering harlot’ further compounding the effect. In the 1890s only shallow people – as Wilde might have said – didn’t judge a book by its cover.

By chance, though, Beardsley did not design what many considered to be the most characteristic volume of the period, Silverpoints (1893), the long slender book of determinedly decadent verse by Wilde’s protégé (and the namesake of Dorian), John Gray. Its apple-green boards, stamped with a motif of gold fleurs-de-lis and wavy lines, and the daringly sparse arrangement of its exquisitely wrought poems, were the work of the artist Charles Ricketts (London Library members can get some faint sense of his design from the 1973 facsimile edition of the book). It was the restrained beauty of this volume that prompted Ada Leverson (‘the wittiest woman in the world, ’ according to Wilde) to suggest that Wilde himself ‘should go a step further than these minor poets … [and] publish a book all margin; full of beautiful unwritten thoughts, and have this blank volume bound in some Nile-green skin powdered with gilt nenuphars and smoothed with hard ivory, decorated with gold by Ricketts (if not [by his companion and fellow-artist] Shannon) and printed on Japanese paper’ . Wilde, delighted with the idea, had replied, ‘It shall be dedicated to you, and the unwritten text illustrated by Aubrey Beardsley. There must be five hundred copies for particular friends, six for the general public, and one for America. ’

Gray was not, of course, Wilde’s only literary disciple. Many of the young men of the 1890s looked to Wilde and his works for inspiration – young men like Lord Alfred Douglas, Robbie Ross and Robert Hichens (author of the satirical novel The Green Carnation, published in 1894). Few of these neophytes, however, managed to transcend his influence. A conspicuous exception was Max Beerbohm.

In 1894, while still a precocious undergraduate at Merton College, Beerbohm used to shock his Oxford contemporaries by claiming that he had only read three books: W.M. Thackeray’s Four Georges (1860), Edward Lear’s A Book of Nonsense (1846), and Intentions (1891) by Wilde. For him Wilde’s collection of essays and ‘duologues’ was a sacred volume. It opened up a new vision of the world to him. He always referred to it as ‘the Book’ , and certainly he learnt much about studied paradox, wit and subversion from its pages.

This learning – absorbed and made personal – he poured into the sparklingly irreverent essays – ‘A Defence of Cosmetics’ , ‘A Note on George the Fourth’ and ‘1880’ – that he contributed to the early numbers of the Yellow Book. Although Beerbohm is remembered now, if he is remembered at all, as the author of Zuleika Dobson (1911), the mock-tragic tale of a beautiful young woman causing havoc amongst the undergraduate population of Oxford, he was essentially a figure of the 1890s, and remained one until his death in 1956. It was the 1890s that established his fame, and coloured his outlook on life. He belonged, as he said, ‘to the Beardsley Period’ .

He provides, too, the best introduction to the period – to its charm, its absurdity, even its pathos. Seven Men (1919), a collection of five short stories, provides a wonderfully funny and allusive portrait of the ‘Yellow Nineties’ , with its warring minor conteurs, Hilary Maltby and Stephen Braxton; its doomed poetic dramatist, ‘Savonarola’ Brown; and, best of all, its ‘dim’ poet, Enoch Soames.

The 1890s was an age of minor poets – all-but-forgotten figures such as Theodore Wratislaw, William Theodore Peters and Arthur Symons. Beerbohm’s Soames, author of the critically ignored collection Fungoids, had not, in 1897, achieved even their level of success. He consoled himself, however, with the thought that his genius would be recognised by future generations. Obsessed with his notion, he sells his soul to the Devil in order that he might travel a hundred years into the future to visit the Reading Room at the British Museum, to see if his fame has grown over the course of the decades. He is dismayed to discover that, a century on, he is known only as a fictional character in Beerbohm’s short story.

If Soames had visited St James’s Square, rather than the British Museum, he would have enjoyed a moment of elation. The London Library catalogue does indeed list a volume under his name: Enoch Soames: The Critical Heritage, edited by David Colvin and Edward Maggs (2001). The elation, however, would have been brief. At the bottom of the page, the librarian has added the cruel qualification: ‘Subject: Soames, Enoch (Fictitious Character). ’ .