6 minute read

D. From the Archive

FROM THE ARCHIVE

Letters to librarians are full of surprises

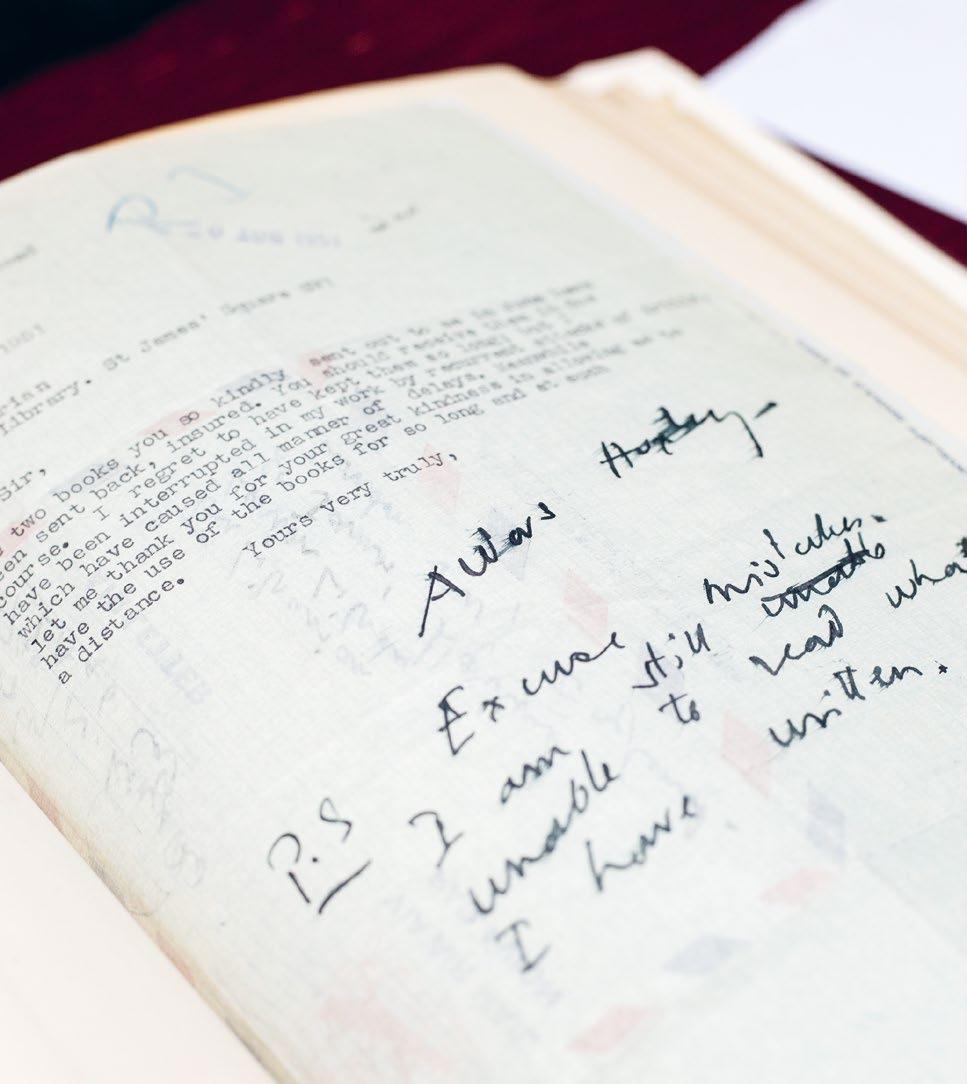

Coming from names like Somerset Maugham, George Bernard Shaw, Barbara Cartland and the exiled Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini, notes about routine book loans sent to librarians past have more life in them than you might expect. Sometimes this member correspondence, now kept in the Library’s archive, offers something quite personal. A 1951 air mail letter from Los Angeles was typed by Aldous Huxley – who suffered from poor and deteriorating eyesight for much of his life – and thanked the Librarian for the books he received some months ago. “I regret that I have kept them so long,” he wrote. “But I have been interrupted in my work by recurrent attacks of iritis which has caused all manner of delays.” His letter ends with a touching postscript written in his increasingly illegible hand: “Excuse mistakes. I am still unable to read what I have written.”

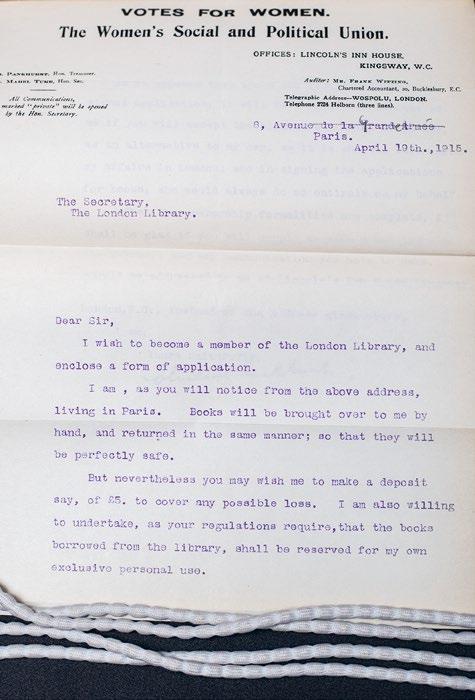

More formal is a two-page letter typed on Women’s Social and Political Union stationery and dated 19 April 1915. It was sent by suffragette Christabel Pankhurst, then living in semi-exile in war-torn Paris, and contains her application for London Library membership. With hostilities on the Western front intensifying (she was writing

six days before the second battle of Ypres), Pankhurst reassures the Librarian: “Books will be brought over to me by hand, and returned in the same manner; so that they will be perfectly safe.” She offers a deposit of £5 to cover any books lost en route. Her letter also confirms that suffragette Grace Roe – released from prison the previous year as part of a government amnesty and Head of Operations for the WSPU – was Pankhurst’s contact in London dealing with her Library book borrowings.

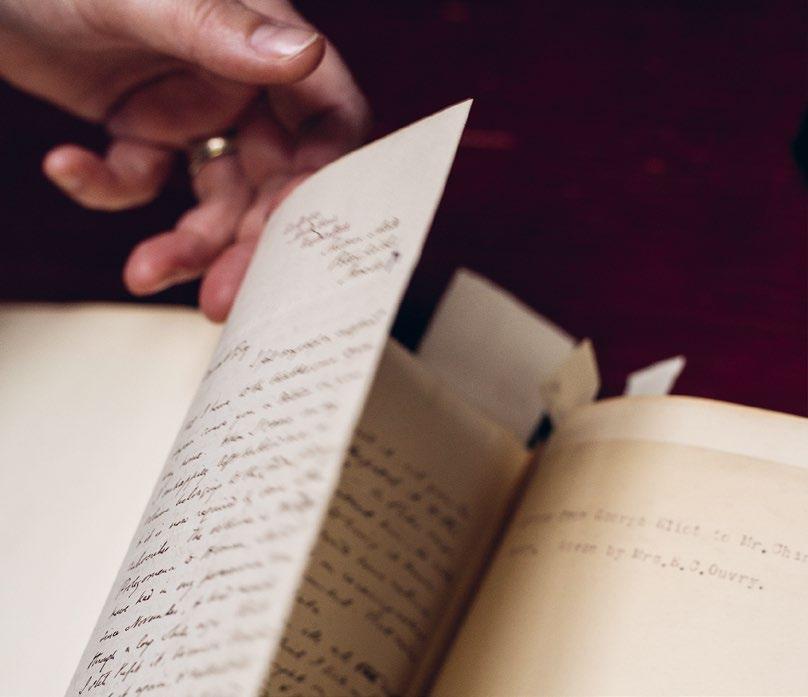

A snapshot of George Eliot’s domestic life is contained in a three-page letter from May 1871 to her stepson George Henry Lewes (“Dearest Boy” from “Mutter”). Describing her recent illness and reporting that “Pater remains jolly”, Eliot is chiefly concerned to address an overdue London Library book – Friedrich August Wolf’s Prolegomena to Homer – recently requested by another member. Eliot had kept this somewhat obscure scholarly work for five months, relying “too confidently on the unlikelihood that anyone else would ask for it. Now however, by way of Nemesis, some student turns up who wants the said volume.”

In her letter she apologetically asks Lewes to find the book. “This much is certain,” she writes. “It is in one of the bookcases in my study.” With hundreds of books in her possession, Eliot thoughtfully offered further assistance, providing a description of the overdue book’s cover and the note: “It is very probable that it is in the upper shelves, or else in the middle cupboard, of the long bookcase that used to be in the drawing room in Blandford Square.” The Library still has a copy of Wolf’s Prolegomena from that time, suggesting Lewes succeeded in his mission.

Less successful was the Library’s rather desperate attempt to involve Stanley Kubrick in a hunt for unreturned books borrowed by novelist Gustav Hasford. Hasford had served as a military journalist during the Vietnam War and in 1979 published the bestselling novel The Short Timers, which was eventually adapted into Kubrick’s feature film Full Metal Jacket. In January 1987, shortly before the film’s release, the Librarian contacted Kubrick about Hasford “in the hope that you may know his current whereabouts”, as “I am anxious to locate him, simply to recover the books”.

The Librarian was right to be concerned. It turned out that Hasford was already wanted for grand theft in California for stealing from the Sacramento Public Library in 1985. Three years later, 10,000 stolen books from libraries across the US, UK and Australia were found in his possession and he was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment.

While the Library’s letter to Kubrick is a model of polite – if anxious – restraint, the Librarian was unable to hold back when berating a careless member five years earlier: “We have just received back from you the copy of FH Hinsley, Power and the pursuit of peace, which you borrowed on 6th January 1982, and I am writing to protest in the strongest possible terms about the condition of this book.

“When my colleagues opened it to cancel the loan, they found inside the front end-papers the squashed bodies of 13 dead houseflies. Their reaction was one of instant disgust, and it is one I share.” The book was rebound in 1997 and thankfully no longer bears witness to the carnage that took place inside its covers. •

COLLECTION STORY

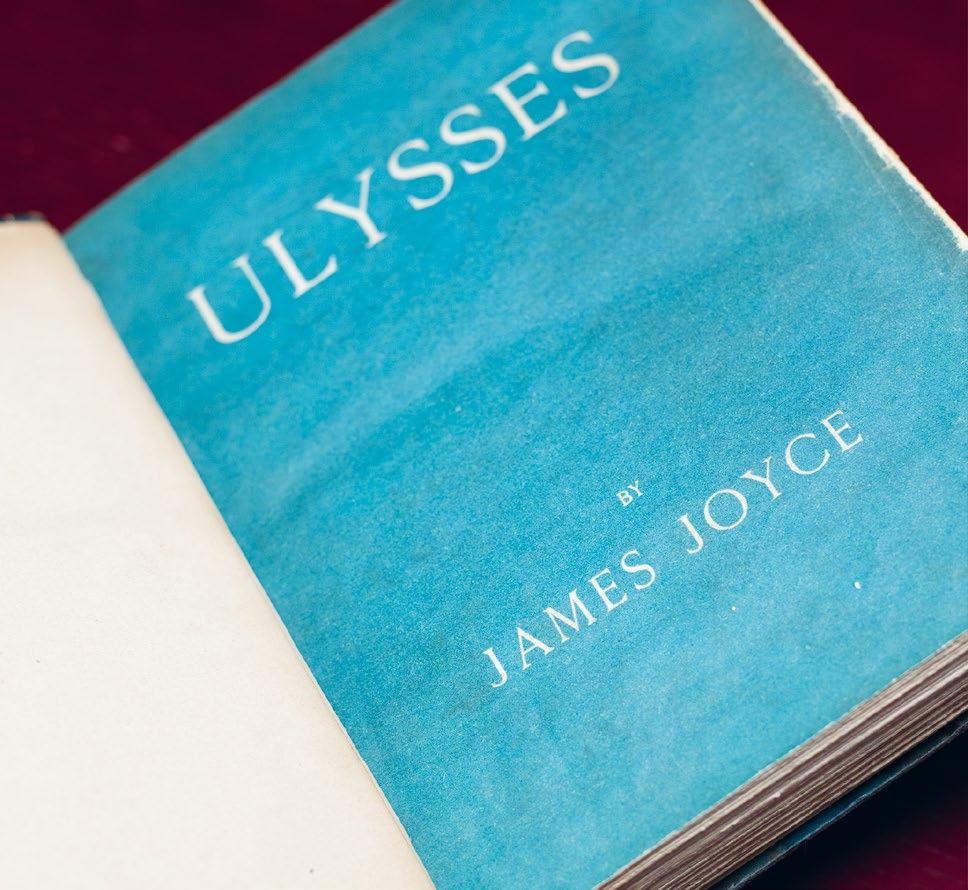

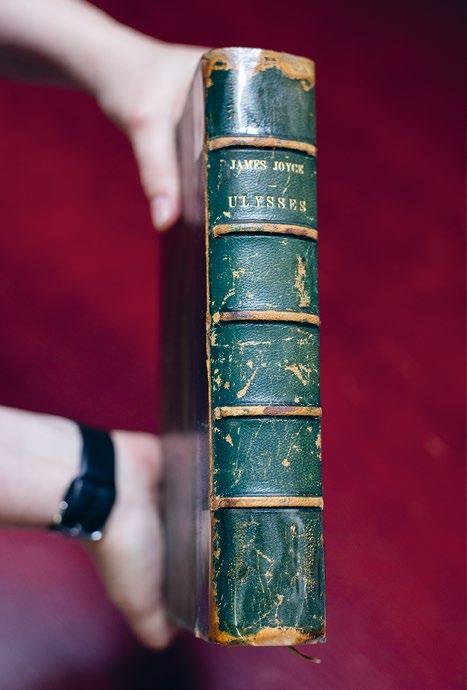

The Library holds a first edition of a classic work that divided opinion even before it was published a century ago

This February marks the 100th anniversary of the publication of James Joyce’s masterpiece, Ulysses. Written between 1914 and 1921, it is regarded as one of the first great works of modernist literature. Before appearing as a book, it began in serialised form in US journal The Little Review from March 1918 to December 1920, and sections of the novel also appeared in London literary journal The Egoist, in 1919. These early serialisations soon ran into trouble.

Three of the chapters appearing in The Little Review were banned by the US Post Office before Joyce’s notorious Nausicaa episode appeared in 1920, which led John S Sumner, Secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, to instigate a prosecution for obscenity. At the trial in 1921, the magazine was declared obscene and, as a result, Ulysses effectively banned in the US (until a court case reversed the ruling in 1932).

Joyce was resident in Paris at this time and had become part of the literary circle surrounding Americanborn bookseller and publisher Sylvia Beach. She agreed to publish the work in its entirety, suffering significant debts as a result, and released 1,000 numbered copies through her Shakespeare and Company publishing business on 2 February 1922, Joyce’s 40th birthday.

The print run of the first edition consisted of 100 signed copies on fine Dutch handmade paper sold at 350 francs, 150 copies on vergé d’arches paper at 250 francs, and 750 copies on less expensive linen handmade paper – one of which, copy no 316, is owned by The London Library.

Throughout the 1920s, the US Post Office Department burned copies of the novel and it fared little better in the UK, following the intervention of Sir Archibald Bodkin, the famously reactionary director of public prosecutions. Offering his opinion to customs authorities on whether to block its import, Bodkin acknowledged: “As might be supposed, I have not had the time, nor may I add, the inclination to read this book.” (He only managed pages 690 to 732.) Nonetheless he was able to advise that, “In my opinion the book is obscene and indecent… It is filthy and filthy books are not allowed to be imported into this country”. The novel was banned in the UK until 1936.

The Library’s treasured first edition came through a bequest made by Dr Ripley Oddie, medical consultant and director of Bayer Products, who died in 1959 at age 57. Oddie was fascinated by Ulysses and studied it carefully in his spare time. He was not the only fan. TS Eliot – Library President at the time Oddie made his bequest – had been greatly influenced by the work at the start of his own career. Writing in The Dial magazine in November 1923 (a year after his own modernist classic The Waste Land was first published) Eliot wrote: “I hold this book to be the most important expression which the present age has found; it is a book to which we are all indebted, and from which none of us can escape.” •