11 minute read

THE MEMOIRS Of JOHN ADDINGTON SYMONDS

Amber Regis describes her editing of the Memoirs of the historian, poet and essayist, whose handwritten autobiography, with all its secrets, has been secured in the Library Safe since 1926.

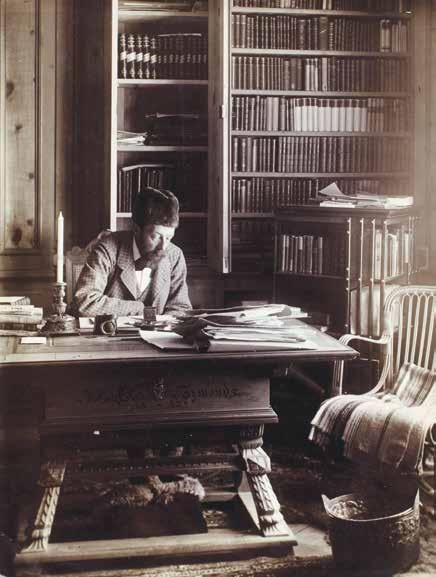

John Addington Symonds in his study at Am Hof, his house in Davos in the Swiss Alps, where he lived during the winter with his wife and their three daughters, from 1867 until his death in 1893. University of Bristol Library, Special Collections (DM377).

In the basement of The London Library, there is a bust of Edmund Gosse. This work, by William Goscombe John, was promised to Gosse by many of his friends on the occasion of his seventieth birthday and unveiled a year later, in 1920, at a grand ceremony at the home of Arthur Balfour. Literary critic, biographer and poet, Gosse was elected Vice President of The London Library, his bust’s future home, in 1922. In this capacity he would negotiate one of the Library’s most extraordinary acquisitions.

In late 1926 Gosse found himself the joint custodian, with Charles Hagberg Wright (Librarian, 1893–1940), of several boxes filled with letters and manuscripts entrusted to his care by Horatio Forbes Brown, minor poet and historian of Venice, recently deceased. These boxes did not contain Brown’s own papers, but rather were filled with material he had long preserved and protected: the papers of John Addington Symonds (1840–93), including his loose-leaf, handwritten Memoirs.

Symonds had been a famous man of letters: a historian of the Renaissance, biographer of Percy Bysshe Shelley and Michelangelo, translator of Benvenuto Cellini and Carlo Gozzi, poet and essayist. On his death he willed his autobiography away from family hands, bequeathing the manuscript to Brown (as his literary executor) with special instructions to ensure its preservation: ‘I want to save it from destruction after my death, and yet to reserve its publication for a period when it will not be injurious to my family. ’

The Memoirs recount Symonds’s experience as a homosexual man living subject to Victorian social mores and legal repression, written without hope of an immediate readership but with a strong conviction of the text’s utility as a case study for medical and scientific enquiry, and a testament of his daily struggles to square conscience with desire, to live what he considered to be a good life.

The Library accepted the Memoirs with certain conditions imposed under Brown’s will: ‘the greatest possible discretion’ was to govern access, and publication was prohibited for 50 years. The manuscript was sealed and locked away in the Library’s Safe, but some of its secrets were already known. On receiving the text after Symonds’s death, Brown mined it for raw material, building and compiling an authorised biography of his late friend. Though dutifully sanitised, clues to the autobiography’s sexual content were present in Brown’s published work, though only accessible to those with the knowledge required to decipher Symonds’s coded discourse: his references to ancient Greece and Walt Whitman, to ‘passing strangers’ and l’amour de l’impossible.

The manuscript’s seals were broken in 1949 when the Library Committee granted permission for Katharine Furse, Symonds’s youngest daughter – a decorated military nurse and Dame Grand Cross – to read her father’s autobiography. Already familiar with his sexual struggles, Katharine was far from shocked by its revelations; instead, she found it a comfort and relief to read her father’s story in his own words. But one thing seemed to trouble her: Symonds’s account of his childhood sexuality. She feared this section, with its frank treatment of prepubescent sexual fantasies and practices, might shock potential readers, and wrote to the Library’s President, Lord Ilchester, suggesting a few pages be lightly edited. The request was politely refused.

During the 1950s, Symonds’s looseleaf manuscript was bound into two large volumes and a typescript copy prepared – preservation measures taken by the Library in response to its decision to relax restrictions on access. Scholars were now able to consult the manuscript, and one of the first to take advantage of this opportunity was E.M. Forster (himself a member of the Library Committee). Forster copied sections of the Memoirs into his commonplace book, bemoaning the impossibility of publication under Brown’s embargo: this would expire in 1976 but, he asked, ‘Would anyone who reads this remember that?’

Pages from Catherine Symonds’s diary form part of her husband’s manuscript, ‘The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds Written by Himself’, which is located in the Safe at The London Library.

Forster’s fear that Symonds would be forgotten, the victim of an enforced silence outlasting his readers’ curiosity, proved unfounded. In 1961 the Canadian biographer Phyllis Grosskurth advertised in the Times Literary Supplement, seeking information on the fate and whereabouts of Symonds’s letters and manuscripts. She was researching a doctoral thesis at the University of London on Symonds’s literary criticism, and was determined to uncover the surviving paper traces of his life. Stanley Gillam (Librarian, 1956–80) responded to the notice, inviting Grosskurth to the Library to read the autobiography. Soon after, she was commissioned to write a new biography, the first to deal frankly and openly with Symonds’s homosexuality. Brown’s embargo was still in place, and Grosskurth was unable to quote directly from the manuscript (unless material had previously appeared in Brown’s censored biography), but she succeeded in bringing the Memoirs, irrevocably, to public notice.

In the years that followed Grosskurth returned to Symonds’s life and writing, this time as his editor. Once Brown’s embargo had expired, she prepared an abridged edition of the Memoirs, published in 1984, removing some 50,000 words to produce a streamlined narrative of sexual development. (The American edition was sensationally subtitled, ‘The secret homosexual life of a leading nineteenth-century man of letters. ’)

Symonds had spent three intensive months, from March to May 1889, writing and compiling his manuscript. Ninety-five years later, the resulting text was scattered: part-published by Brown, part-published by Grosskurth, his autobiography remained locked in the Safe at The London Library. This is how matters stood until the publication this month of my book, The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds: A Critical Edition (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017). This volume is the culmination of happy hours spent in the Writers’ Room at The London Library, punctuated by fleeting visits to Gosse’s bust in the basement. It is the first edition to reproduce the autobiography entire, reuniting and combining the narratives made public by Brown and Grosskurth, interspersed with material left unpublished by both, hidden and closeted until now. It was a privilege to work on Symonds’s autobiography as its third editor, but it is important to acknowledge that my labours were collaborative. I am truly indebted: to Symonds’s bravery in committing his life to paper; to the work of Brown and Grosskurth as previous editors; to the Library as custodian; and to the patience of Library staff who sat across from me, day after day, supervising my use of the manuscript.

There is one thing, however, that a print edition cannot do. It cannot recreate our haptic encounter with the material object: the sight and feel of Symonds’s handwritten pages. Print smoothes; it gives the impression of order, coherence, completion. But the manuscript is not a seamless text; it is replete with eccentricities and contingencies. My edition is not a surrogate; it is an artefact in its own right, a distinct version of Symonds’s text. As its editor, I hope the book will encourage readers to seek out the manuscript, to leaf through its pages, to discover its loquacious materiality.

Here I cannot hope to do full justice to the manuscript-as-object, but some brief forays, appropriately digressive and disjointed, might serve to pique interest (and the curious are reminded that permission to read the manuscript can be sought from the Enquiries desk in the Issue Hall).

Towards the end of his Memoirs, Symonds pauses to reflect on the problems of writing a life. The egotism required for autobiography, far from beautifying the sitter, likely results in ‘the artistic error of depicting a psychological monster’ . For Symonds, ‘The report has to be supplemented indeed, in order that a perfect portrait may be painted of the man’ .

A significant portion of material in the Memoirs is supplementary, of a different order to the broadly linear, retrospective narration that forms its backbone. Symonds assembled the manuscript, collecting letters, diaries and poems to include among its pages. Many are the work of his own pen, his younger self: homoerotic poems, set in type and privately printed, are cut and pasted into the text; passages of lyrical prose are transcribed from letters and diaries. These extracts and documents provide an important counterbalance to autobiographical hindsight, with its unifying, simplifying and forgetful gaze. ‘No autobiographical resumption of facts after the lapse of twenty-five years, ’ he claimed, ‘[was] equal in veracity to such contemporary records’ .

A small number of Symonds’s supplements, however, are the work of other hands: a letter from his sister’s governess, Sophie Girard; a letter from his former pupil and lover, Norman Moor; 9,000 words taken, quite literally, from his wife’s diary. Hearing these voices interrupt Symonds’s narrative is remarkable – wives and governesses do not often take centre stage in the written lives of Victorian men, and the figure of the male lover is all but absent. What is more, the sight and touch of these handwritten documents enables a different kind of encounter: contact, and imaginative re-embodiment.

Moor’s careless, hard-to-read script, dealing frankly with the sexual culture of the British public school, bespeaks the confidence and privileges of his middleclass masculinity. Girard and Catherine Symonds, by contrast, write with looping precision in a legible hand, their letters well formed, and there is a pathos in the care taken over the writing of these documents. Girard’s letter was composed at Symonds’s request, an account of his childhood character, penned by a woman once in the family’s employment who continued to depend upon his annual contribution to her income. Catherine’s diary, taken by unknown means and without assurances of permission granted, recounts the young couple’s courtship and first year of marriage, her private reflections placed before an unlooked-for public readership.

The Memoirs manuscript comprises more than six hundred pages of varying size, colour and contents, the work of different hands, drawn from the memories and paper traces of more than 50 years. As such, the manuscript-asobject is a work of collage, of assemblage. There is a hole in the manuscript – not the work of some archival stowaway feasting on paper, but the work of a knife or razor: ‘There is no doubt that Dr. [ ] passed for an eminently pious man. ’ Luckily, the editor does not have to search far to fill the blank. Just above this hole, a name is written in what appears to be Symonds’s hand: ‘Vaughan. ’

Charles John Vaughan was headmaster at Harrow until his sudden resignation in 1859. In chapters of the Memoirs dealing with school and university, Symonds claimed to have been the confidante of a pupil, Alfred Pretor, as he engaged in a clandestine relationship with Vaughan. Towards the end of his first year at Oxford, Symonds confessed this secret to a tutor, who persuaded him to tell his father. According to the Memoirs, Symonds senior forced Vaughan’s resignation and withdrawal from public life.

Symonds inscribes Vaughan’s name upon his manuscript pages, over and over again. But only once is the name cut out, obliterated, before re-inscription – the return of the repressed. In print, my edition can only note and describe this eccentricity, with an accompanying photograph buried in an appendix. But when turning the pages of the manuscript, this presence (or rather, absence) tempts one to speculate. I see in (or through) the hole an image of Symonds as self-censor, distractedly taking a knife to the body of his work, removing Vaughan’s name to ease, albeit momentarily, a guilty conscience – guilt at the broken confidence that precipitated Vaughan’s fall; guilt at the sympathy he felt for a man whose desires he shared; and guilt at his own ‘passing’ through life, a respected man of letters, husband and father, forced to hide or deny the men he loved.

The paper bearing Vaughan’s cut-out name is not the only missing piece of the Memoirs. Promised pages and supplements are absent: white, unfilled spaces mark the place where passages from letters and diaries might have been transcribed, if Symonds had finished the task; and five leaves are missing from the page-number sequence (MS 550–5). Fixed in print, these lacunae disappear from the text. But an encounter with the manuscript-as-object reveals the unfinished, fragmentary nature of Symonds’s self-portrait.

Symonds spent the last years of his life reading and revising his Memoirs. Emendations litter the text: deletions and substitutions, passages struck through with revisions above and below. Symonds appears to have worked through the manuscript with a blue pencil (or standard pencil, when the editor’s tool was not close at hand), sometimes reinscribing his corrections in ink. My new edition records significant changes in endnotes, but otherwise the text appears static, immutable, as if Symonds could only have told his story in these very words. But the manuscript tells things differently, variously. These handwritten pages reveal the work-in-progress, shaped by the difficulties experienced in choosing words to speak the unspeakable, to write about same-sex desire in a way that resisted blame and disapproval – on different occasions, Symonds substitutes ‘self-indulgence’ for ‘sin’, ‘malady’ for ‘infamy’, for example.

Symonds’s editing pencil is not the only one to mark the manuscript – his pages still bear the trace of Brown’s editing. Sections of text are closed off in brackets and marked for deletion: sometimes these interventions are signed ‘HFB’, and sometimes they can be identified as Brown’s work by their correspondence to his published biography. These lines and marginal notes animate the manuscript’s contested legacy and the competing versions of Symonds’s life that have been extracted from its pages. Reading the manuscript-as-object, therefore, was an uncanny experience for this particular editor. Constantly reminded that I walked in dead men’s shoes, the ghostly trace of Brown’s pencil proved my own future obsolescence. One day, most likely, another editor will sit down with the Memoirs manuscript and begin a new chapter in its history.