12 minute read

Back Stack Adventurers - Jeremy Treglown

You just go to the shelves. Well, first you go up a few steps into History – these are the Back Stacks and it’s basically still the ground floor but it’s marked ‘Level Three’ . Turn sharp right twice, down two vertiginously perforated iron staircases to Level One, Topography. The regions are organised alphabetically, so Spain is – no, not in ‘Russia → Zululand’ , as it happens – you go a bit further to the right, then left past Arctic, Australia and British Columbia, up a couple of steps and you’ll see Scotland, Serbia & Jugoslavia ahead: there you are. Um, I may have, ah … no, that aisle’s blocked by a lift, so we go back, then around – I’ll just switch on these lights – New Guinea, Palestine & Syria, try right once more to the back of the lift. And immediately left, Sierra Leone, and here we are in Spain. Warm? Yes, me too.

Even by The London Library’s own standards its Spanish holdings are quirky and sprawling. Topography alone houses 27 military-style metal shelves full of Hispanic material, each shelf carrying about 30 books, among them relevant elements of a collection given to the Library by Joseph Conrad’s contemporary and friend, the part-Spanish Scottish-nationalist Harrovian socialist politician and adventurer R.B. (‘Don Roberto’) Cunninghame Graham, aka ‘the Gaucho Laird’ , in memory of his young wife Gabrielle.

Alphabetically by author, the books start with John Leycester Adolphus’s Letters from Spain, published by John Murray at Albemarle Street in 1858, and end with La Itálica (1886) by Fernando de Zevallos, a priest at the monastery of San Isidoro del Campo, Seville. ‘La Itálica’ was the name of the ancient Roman colony now better known as Old Seville, and Fr. Fernando’s book represents just one of travel writing’s multitudinous forms: an account of a journey not geographical – the medieval monastery is next door to, indeed on top of, some of the Roman remains – but in time. ‘I thought I could hear the noise of a vast crowd sitting on these steps, ’ Fernando wrote of the amphitheatre, ‘and could see the grandest aristocracy the world has ever known, knights and venerable magistrates of the Roman Empire thronging the rostrum which today is level with the ploughed fields’ .

But I mean to focus on Anglophone travellers on the peninsula so must ignore books in Spanish (and also, here, French, German and Italian), hard though that can be, particularly when they impose themselves physically: the seven decadently white-green-andgold-bound volumes of P. Gabriel de Henao’s Averiguaciones [Findings] de las antigüedades de Cantabria (1894–5), for example, the Library’s copy of which is flamboyantly dedicated by the author to the pretender ‘King’ Carlos VII: ‘receive this little tribute as proof of the love and unshakable loyalty offered you by your loyal vassal. ’ Nor must I get distracted by associations (I’m not the only Library member to have been lunched on a near- Spanish scale in Albemarle Street by the sixth John Murray). With these restrictions in mind it’s just a matter, as I said, of going to the shelves and starting at the beginning.

But what beginning? Alphabetically, the first relevant work after Adolphus’s (‘The only apology which the author can seriously make, ’ Adolphus writes, ‘for adding one to the multitude of slight books on Spain is that having some practice in this kind of writing, and habits of labour to which the exercise was congenial … ’: if only pitches like that worked with today’s publishers) is by A.C. Andros. His cheerily titled Pen and Pencil Sketches of a Holiday Scamper in Spain (1860) begins with a colour sketch of picnickers in the palm forest at Elche, a fold-out route-map and a picture of a bullfight with a steam train in the background. These are followed by some mood-music perfect for a reader benighted in this mid-Victorian cellar on an unexpectedly sunny day: ‘The London season of 1859 is nearly over. The parks and gardens are rapidly emptying, the theatres and opera-houses are beginning to manifest signs of shutting up, the Royal Academy is about to be closed … the heat is becoming intolerable, and everyone is hurrying out of town … I can brook no further delay in the metropolis, and long to flee from its deserted streets. ’ Does anyone know who Andros was? This seems to be the author’s only book. Anyway, alphabetical order of author, whatever curiosities it yields, is no help. I’m where I started more than a decade ago.

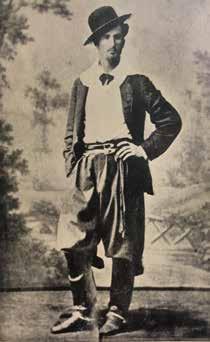

Gabrielle de la Balmondière in a portrait by George Percy Jacomb- Hood. From A.F. Tschiffely’s Don Roberto, Being the Account of the Life and Works of R.B. Cunninghame Graham 1852–1936 (1937).

Back then I was thinking about, and wanted to contextualise, V.S. Pritchett’s first book, Marching Spain (1928). In his own mind the young Pritchett was an explorer, an outsider, a pioneer. ‘I am not ashamed of my fears for they are my adventures, ’ he wrote about crossing the river Tagus in flood by the unnecessary means of scrambling along a dilapidated railway bridge, staring down at the water between broken sleepers (probably quite like the higher catwalks in the Back Stacks). Who else, before him, knew anything about Spain, least of all about the region through which he described himself walking, Extremadura?

Quite a lot of people, in fact, even if one excludes the Extremeños themselves, as I found by rearranging my notes in historical order. Here was Robert Semple, for example, who, having done a bit of spying around Badajoz’s as yet unbesieged medieval walls on the eve of the Peninsular War, found as he and his friends set off at dawn for Mérida that the town’s gate was unreasonably ‘clogged with peasants’ going to market. ‘We had no resource but to spur up our horses, ’ he records in Observations on a Journey Through Spain and Italy to Naples (1807), ‘and force our way through with no small detriment to many a panier of figs and apricots’ .

Illustration from A.C. Andros’s Pen and Pencil Sketches of a Holiday Scamper in Spain (1860).

Extremadura borders Portugal and, before both countries joined the EU, was a necessary stopping place on the way between Madrid and the Atlantic. One of Semple’s purposes was to offer a ‘Post Guide’ for horse-drawn travellers, listing distances between stages, prices per traveller for each stage including taxes, and relative costs of using post-chaises and ‘solitaries’ . But while many people passed through this austere region, few stayed longer than they could help, so the more persistent could cultivate an illusion that it was ‘almost virgin territory’ . The ironic phrase is that of Jesús A. Marín Calvarro in his 2002 study of early Anglophone narratives about the area, Extremadura en los relatos de viajeros de habla inglesa (1760–1910) – works whose barest publication details take up half a dozen pages of bibliography and next to none of which Pritchett knew. For readers then as now the attractions included vicariousness, an indulgence surprisingly often enjoyed by the writers, too. Although Richard Ford travelled assiduously to prepare his bestselling Handbook for Travellers in Spain (1845), there were still many places he didn’t get to. As Ian Robertson shows in his 2004 biography of Ford, he never let this prevent him from writing about them, lifting descriptions by previous writers and embellishing them.

On Pritchett’s part there were milder deceptions. Affecting an explorer’s innocence may have been an excuse for neglecting accounts by most of his predecessors, but he was no newcomer. He had lived in Spain as a reporter in 1924–5, travelling widely there with his Anglo-Irish first wife Evelyn Vigors and filing vivid colour-pieces for the Christian Science Monitor. Those journeys were often made by car. Pritchett himself didn’t drive but Evelyn’s role is recorded with what may have been a touch of irony in her Spanish driving licence, where she gave her profession as ‘conductora’ – ‘driver’ . Her husband’s 18-day walk from Badajoz to León in the spring of 1927 was genuine enough, but some of the incidents he described came from previous visits. More seems to have happened to him than one would expect during so short a stay, because some of it didn’t happen when he said it did, or not by the means of locomotion he implied.

Most travel writers are fabulists. Along with their sheer writing – their brio, their vividness – it’s what distinguishes them, in degree if not in kind, from anthropologists, geographers, topographers. Their ambitions may be quite modest, like those of F.H. Deverell, who in All Around Spain by Road and Rail (1884) tells us he went to Extremadura to see ‘ “the abomination of desolation” spoken of concerning that province … and to enquire about the locusts said to swarm there’ . (Deverell also took the opportunity to visit ‘our wonderful English possession, Gibraltar’ , which figures in these books in ways that now stir an anticipatory nostalgia.) Or the approach can be grandiose. When Ford wanted a Spanish base for his family, he rented the governor’s suite in the then half-derelict Alhambra for months at a time.

Travel writers can no longer get away with pretending they are pioneers. The best of them among our contemporaries capitalise on being part of a continuum. Revisiting these travelogues I found many of my earlier impressions confirmed, particularly that Extremadura was long imagined as one of Western Europe’s last wildernesses. The resentful insular ‘debate’ over Brexit, however, brought something else into focus. How many British clichés about abroad can be traced back to even the best educated of our all-powerful, all-scorning ancestors? The personally adventurous, trend-setting Elizabeth Fox, Lady Holland, who during visits to Spain in 1802–5 and 1808–9 read Don Quixote in the original and tried to pass as Spanish by putting on ‘some black petticoats and draperies’ , dismissed much of what she saw as simply ‘bad taste’ , including churches which she said lacked ‘any pretensions even to architecture’ . As for her contemporary Robert Southey, poet laureate and a noted Hispanist, there can’t have been many writers whose official pronouncements have been so at odds with their private observations. ‘Spain! still my mind delights to picture forth/ Thy scenes’ , he rhapsodised, and again,

… still the charmed eye Dwelt lingering o’er Plasencia’s fertile plain, And loved to mark the mountain’s bordering snow, Pale purpled as the evening dim decayed … … Oh pleasant scenes!

But his late 1790s Letters Written During a Journey in Spain are full of irritable mutterings against ‘Bad wine, beds even worse than usual, no towel, and a dear reckoning’ , and villages whose habitations ‘are fit only for the pig part of the family’ . If there was nothing new about this, nor was there much to support the Enlightenment idea that travel opens minds. Among the British, the opposite has all too often been the case. In Through Spain to the Sahara (1868), the muchtravelled, prolific Matilda Betham-Edwards, having commented (was she the first?) that ‘In Spain the railways are not made for travellers but travellers for railways’ , turned her scorn on a regimental parade: ‘The soldiers were the shabbiest set I ever saw, the music poor, and the whole thing spiritless. ’ Twenty-five years later, Frances Elliot, the popularity of whose books on exotic places owed something to a promise of undemandingness in titles like Diary of an Idle Woman in Constantinople (1893) and Roman Gossip (1894), wrote breathlessly about Spain’s past but was brisk in her exasperation at its present: ‘A peseta or two settles the sour-faced official, and I pass out into a yard, all mud and slush in winter, and dust and flies in summer, carrying my own bags; for the brown-faced natives on the platform cannot be bothered with such unremunerative trash. ’

And so to Bart Kennedy (1861–1930), a ‘tramping’ writer and former seaman from a working-class family in Leeds, who went to the peninsula at the beginning of the twentieth century ‘armed with a revolver, a passport, and no knowledge of the language … to see how things looked to the absolutely new eye’ . Firearms apart, you can meet Kennedy’s resolutely non-Hispanophone descendants in any Spanish resort. ‘How the row started I haven’t the faintest idea, ’ he begins one chapter of A Tramp in Spain (1904). ‘We were all together in a wineshop …’ Within a few pages, one man has grabbed another by the throat, another has thrown a knife, and the narrator, having fired his revolver ‘just in front of’ a Spaniard in the street outside, has been arrested. Before we blame today’s redstomached hedonists for their arrogance and ignorance it’s worth asking where it all came from. The trickle-down theory may be discredited in economics but visà-vis Anglo-Saxon Attitudes might repay further investigation.

‘Plasencia – A Street’, from V.S. Pritchett’s Marching Spain (1928)

Happily, there have been many exceptions: British people who have enjoyed foreign places and people without having to treat them as eccentric or inferior. Pritchett was one. Others included Jan and Cora Gordon, widely travelled painter-musicians who after the First World War found themselves in a depressed London, gazing out of their ‘low-ceilinged flat … upon a sky covered with flat cloud’ , wondering ‘how we might escape in order to seek for our original selves – if they were not irretrievably lost’ . So they went to Spain and wrote and illustrated two books about the experience, Poor Folk in Spain (1922) and Misadventures With a Donkey in Spain (1924). ‘I think we went to Spain to look for something that the war had taken from us, ’ they said.

Perhaps they had read Augustus Hare, who advised potential emulators of his 1885 Wanderings in Spain to ‘put all false Anglican pride in [their] pocket, and treat every Spaniard, from the lowest beggar upwards, as [their] equal’ . You must take a foreign country as you find it, Hare wrote: Spain ‘is not likely to improve; she does not wish to improve’ . It was a matter of difference – and, having understood that, one had to allow, too, that it might also even be one of superiority: ‘The Spanish standard of morals, of manners, of religion, of duty, of all the courtesies which are due from one person to another, however wide apart their rank, is a very different and in most of these points a much higher standard than the English one, and, if an English traveller will not at least endeavour to come up to it, he had much better stay at home. ’

‘Spanish Courtyard’ by Cora Gordon, from Jan and Cora Gordon’s Poor Folk in Spain (1922).

Stumbling around the Back Stacks basement at a time when our native offshore-ists were atavistically resuming their primitive woad, it was good to hear generous, cosmopolitan observations being made in an English accent. A reminder, too, as the pound seemed to be heading south of the euro, that for the price of a subscription to The London Library you can always travel vicariously. You just go to the shelves. (Might be worth taking a map.)